Column: Disney needs fixing, but Peltz was the wrong repairman

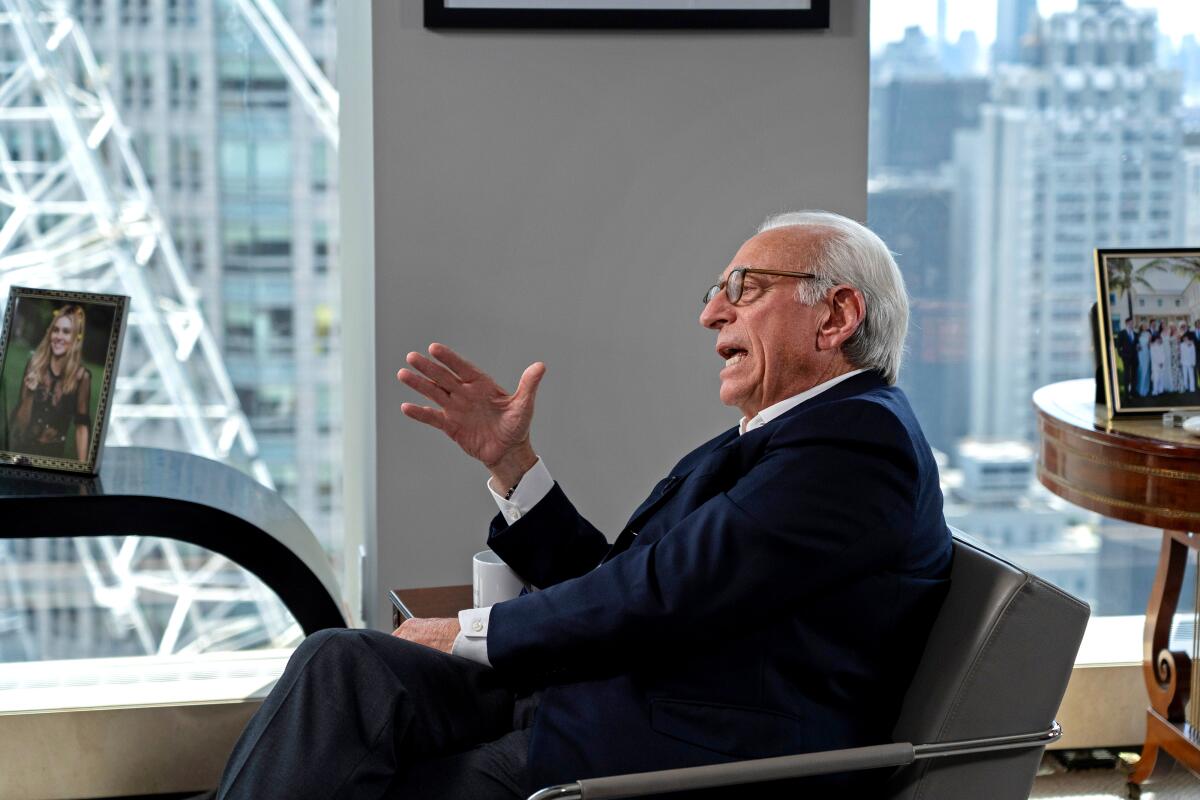

Now that the smoke has cleared from the most expensive proxy fight in corporate history — the $600-million battle between investor Nelson Peltz and the management of the Walt Disney Co. — we can take a breath and ask the question often heard at the end of a bad movie:

“What the hell was that all about?”

The count of shareholder votes Disney announced Wednesday after the close of its annual meeting indicates that Peltz lost his bid for two board seats, as my colleagues Meg James and Samantha Masunaga reported. All of management’s board nominees were elected.

Why do I have to have a Marvel [film] that’s all women? Not that I have anything against women, but why do I have to do that? Why can’t I have Marvels that are both? Why do I need an all-Black cast?”

— Nelson Peltz

This evidently ends a C-suite battle that riveted the financial press for months. Disney Chief Executive Bob Iger can supposedly breathe a little easier, now that Peltz is out of his hair. But he shouldn’t.

The company he leads is still struggling with a raft of problems and uncertainties in its core businesses — the difficulty of extracting profits from streaming services, the hangover of poor results from the pandemic and a series of bombs among its latest movie releases.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Yet, it’s unclear what the proxy battle yielded, other than spectacle. The battle devolved into a contest of personalities more than a debate over how to manage Disney for the future.

Peltz’s chief criticisms involved events from years past, including the acquisition of 21st Century Fox in 2019 and the botched tenure of Bob Chapek, who was appointed as Iger’s successor in 2020 and shown the door in 2022.

Iger returned to his old job then, and has been given through 2026 to set up a new succession plan.

Disney shareholders reject billionaire investor Nelson Peltz, who wanted changes, for a board seat. The hard-fought battle exposed Disney’s challenges.

Peltz, for his part, struggled to make a compelling argument for his own accession to the Disney board. His argument that the company’s management has lost its grip on the market was undermined by its strong performance this year — a 30% gain in its stock price so far this year, largely attributed by Disney’s strong first-quarter net income of $2.15 billion — a 58% increase over the year-earlier period.

That’s not to say that Disney isn’t confronting daunting head winds. In Disney’s case, one merely needs to point to financial results — these are, after all, publicly disclosed.

The proxy advisory firm Instittutional Shareholders Services laid them out last month when it advised its institutional investor clients to vote for Peltz’s election to the board (though curiously not for Rasulo, the former Disney executive).

Disney shares had underperformed the broad stock market “over the one-, three-, and five-year periods through Oct. 6,” ISS observed. Its margins, cash flow and returns on investments had deteriorated over five years and its debt burden had soared.

That last was largely the consequence of Disney’s $71-billion acquisition of 21st Century Fox in 2019, which brought Disney’s long-term debt to $38 billion from $17 billion virtually overnight. (At the end of last year, it was $42 billion.)

ISS and Peltz also criticized the company for its lack of a succession plan for the post-Iger era. This was also a problem hiding in plain sight, since Iger’s chosen successor, Bob Chapek, was fired in 2022 after less than three years in the job — a period in which Iger continually belittled his performance, at first from above while he remained executive chairman, and subsequently from outside. Iger returned as CEO, but the question of his successor remains unresolved.

Despite all that, however, ISS called only for “incremental change” at Disney, evidently expecting that adding Peltz to the board will help to concentrate the other directors’ minds on solutions to the company’s ills.

Disney and Spectrum once again trample their customers’ interests in their bid to squeeze more money from each other.

As is always the case in politics, corporate and otherwise, it’s always easier to identify problems than to articulate solutions. Having established that Disney has problems, Peltz offered shareholders purported solutions in a 133-slide presentation setting forth “the Case for Change.” Before examining that case, let’s examine the tone of the proxy battle.

Throughout the six months since Peltz announced his quest for a board seat, corporate executives and investment sages seemed to feel obligated to take sides. Peltz’s decades-long record gave them plenty to masticate.

The most direct criticism of Peltz came from Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a management professor at Yale who is an unreconstructed fan of Iger’s. Sonnenfeld launched a broadside against Peltz last month by calling him “America’s most overrated activist investor.”

Sonnenfeld and his Yale colleague Steven Tian calculated that in 15 of 22 instances in which Peltz or a Trian representative joined a corporate board, the company underperformed the benchmark Standard & Poor’s 500 index during their board tenure.

For the second time in a year, activist investor Nelson Peltz is battling Bob Iger and Disney to shake up the company and nab two board seats.

Among the losers are General Electric (which had management problems almost no one could easily fix); Wendy’s (where Peltz is chairman and his business partner Peter May and his son Matthew hold board seats); and Unilever, which Peltz advised to keep doing business in Russia despite international sanctions imposed following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

On the plus side are Procter & Gamble, where Peltz narrowly lost a proxy battle in 2017 but was given a board seat by management anyway. P&G arguably gained from the change, as Peltz’s presence helped it simplify a chaotic management bureaucracy that arguably was hampering its performance. But in other cases, Sonnenfeld and Tian wrote, Peltz’s disruptive behavior on corporate boards caused more problems than it solved.

Writers and artists who created novelizations of some of Disney’s most important franchises say the entertainment giant has stiffed them of royalties.

Sonnenfeld and Tian followed their critique of Peltz with an admiring analysis of Iger’s return, in which they said “he is pulling off one of the most remarkable turnaround and transformation stories in media and entertainment history.”

Peltz meanwhile lined up testimonials from his own fans. They included Unilever CEO Alan Jope, who cited Peltz’s “strong track record in the consumer products industry,” and Elon Musk.

In Trian’s presentation to Disney shareholders, Peltz stuck mostly to the area where he claims the most expertise — the board of directors. The board “lacks focus, alignment, and accountability,” he wrote. He observed that about half of Disney’s non-management directors are CEOs or top executives of other companies, including Nike, Oracle and General Motors, though that’s true of almost every board of major corporations.

As it happens, many of Peltz’s criticisms of Disney’s top management are common in corporate America. “Disney’s conformist corporate culture does not accept dissenting viewpoints,” the slide deck stated. “In Disney’s world, management & directors are never at fault.... Executive compensation is not properly tied to performance,” etc., etc.

Aside from tightening up compensation standards to reduce executive and director pay, however, Peltz offered aspirations rather than specifics: The company should “accelerate media profitability,” “clarify strategic focus,” and “review [its] creative engine.”

Peltz called on the company to “right-size” its “legacy media business cost structure,” which is business gibberish translatable into laying off workers and cutting pay. Peltz set a goal of “Netflix-like margins of 15-20% by 2027,” though Netflix is essentially in one business — streaming — and Disney is in streaming, film and TV production,

theme parks, and more. With about $90 billion in revenue, Disney is also about three times the size of Netflix.

Addressing the challenges in park attendance, the technology transition in content distribution, and the other head winds confronting the media and entertainment industry would be a challenge for anyone; its not clear that exhorting the Disney board to push for better profits represented an actionable contribution to the company’s future.

Disney’s money has controlled Florida politics for more than 50 years. Now the politicians are showing their ingratitude.

Take the malady ailing Disney’s creative side, if it’s even a malady at all. Success and failure in the movie business is the most recondite of qualities. One is constantly reminded of the observation by screenwriter William Goldman that in Hollywood, “Nobody knows anything.”

Disney may have figured that it had a couple of surefire hits in its pipeline with “The Marvels” and “Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny,” a sequel in that already superannuated series. Both bombed.

Here again, it was easier for Peltz to identify the shortcomings — after all, the box-office figures were available for everyone to see — than to come up with solutions. He called for Disney to “initiate a comprehensive Board-led review of studio operations and culture, including leadership, processes and workflow.”

What would that even mean, other than having a gang of suits crunch cash-flow numbers and inject themselves into creative decision-making? Would the CEOs and other top executives of General Motors, Oracle, Lululemon and CVS, to mention some of the board members, have much useful to contribute about the “culture” of a creative studio? Anything is possible, but color me skeptical.

To the extent that he weighed in on Disney’s creative output at all, Peltz seemed to grasp the wrong end of the stick. “Why do I have to have a Marvel [film] that’s all women?” he asked a Financial Times reporter in an interview published last month. “Not that I have anything against women, but why do I have to do that? Why can’t I have Marvels that are both? Why do I need an all-Black cast?”

His references were to “The Marvels” and “Black Panther.” The first was an unalloyed disaster, but that probably had little to do with the fact that it was about a team of female avengers. “Black Panther,” on the other hand, was an unalloyed hit, the third most successful Marvel film, with $700 million in worldwide gross to date.

It’s true that Iger said last year that Disney’s creative team was too focused on messaging — “We have to entertain first. It’s not about messages,” he said — but it’s not clear that he was doing anything more than bowing to the partisan backlash against “wokeness,” or that he was pointing to anything genuine.

No one would say that the fifth Indiana Jones film, featuring an 81-year-old Harrison Ford in the title role, failed because it was too “woke.” Does anyone really think it’s wrong for Disney to expand its products’ appeal to Black and Hispanic audiences?

Disney shareholders have reason to hope that the conclusion of the proxy fight will remove a distraction and enable Iger and the board to focus more on the task ahead. Perhaps his foray reminded them of the consequences of failure. Perhaps they’ll be able to show that they had matters in hand all along; if they fail, Peltz can claim that they missed an opportunity by keeping him off the board, but they’ll have bigger problems than an activist investor gloating that he told them so.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.