Column: Disney allegedly has cheated hundreds of writers out of pay for Star Wars and other properties

Given its immense appetite for entertainment content to keep its movie and television pipelines filled, you would think that Walt Disney Co. would do its best to treat its creative talent fairly.

You would be wrong.

For years, Disney has been cheating the writers and artists of tie-in products — novelizations and graphic novels based on some of its most important franchises — of the royalties they’re due for their works. That’s the conclusion of a task force formed by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America and joined by the Writers Guild East and West and several other creator advocacy organizations.

Disney gets away with this by using the exhaustion tactic. They wear people down.”

— Mary Robinette Kowal, Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America

“This is wage theft and it’s very pernicious,” says Mary Robinette Kowal, an award-winning author and past president of the SFWA.

Disney has turned a deaf ear to the task force, which has offered to provide the company with names and addresses of writers and artists who are owed royalties.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“They say individual artists and agents have to contact them,” Kowal told me. The task force has been compiling information about the royalty claimants through its own website, writersmustbepaid.org, and via the Twitter hashtag #DisneyMustPay.

In strictly legal terms, Disney’s responsibilities for royalties may be murky in some cases — in part because the original contracts have varied terms and obligations. Contracts in the comic book industry sometimes may allow for royalty obligations to be extinguished when a property is relicensed.

But there’s little question that the company, which earned $2.5 billion in profit last year on $67.4 billion in revenue, owes a moral responsibility to the people who generate the creative content on which its fortunes are based.

Kowal says that Disney may owe hundreds of writers and artists royalties averaging a few thousand dollars each, with a handful of larger claims reaching $5,000 to $20,000.

Florida Republicans aiming to punish Disney have hit their own voters instead.

“For a freelancer, that’s significant,” she says. Even the larger sums would be drained to nothing in any individual effort to take Disney to court. “For Disney, this is pocket change,” Kowal says. “We want Disney to address this in a comprehensive way.”

This issue has been simmering for almost two years, or since it was made public by the SFWA and Alan Dean Foster, a respected and prolific science-fiction author. Foster signed a contract with George Lucas to write a novelization of the first “Star Wars” movie even before the movie premiered in 1977, when Foster was 30. He then wrote a sequel tied to the concept. He is now 75.

Royalties from the books mysteriously ceased in 2012, around the time that Disney acquired Lucasfilm. So did royalties from the novelizations Foster wrote of the first three “Alien” films for 20th Century Fox — around the time that Fox was acquired by Disney in 2019.

“I thought, well, they’re not earning much right now, and there will be a consolidated royalty statement when there’s enough money to make it worthwhile,” Foster told me. When more time passed without any statements, he asked his agent, Vaughne Hansen, to investigate.

Eventually Disney told her that “they had acquired the properties from Fox and Lucasfilm, but they didn’t acquire the obligations,” Foster recalls. “That suddenly made this an important point of contract law, and not just a question of Mr. Foster’s royalties.”

Foster eventually got paid, but not without lengthy discussions and only after he went public in November 2020.

Disney refuses to comment about the controversy on the record, beyond referring me to a one-line statement it issued that year.

“We are carefully reviewing whether any royalty payments may have been missed as a result of acquisition integration and will take appropriate remedial steps if that is the case,” the company said at the time.

Disney, Florida’s most powerful corporation, greets the state’s attack on LGBTQ+ kids with silence.

But little progress has been made since then, while the ranks have swelled of creative artists reporting that they’ve been stiffed by the entertainment behemoth.

Some of the complaints derive from reprints brought out by companies other than the original publishers of the books or comics. They include “omnibus” editions that compile several graphic novels in single volumes, and which may involve the work of dozens of individual artists.

Even Marvel Entertainment, which agents say is the most cooperative Disney subsidiary in resolving payment gaps, can take a year or longer to do so.

In some cases, according to writers’ representatives, Marvel has agreed to make payments based on its own standard incentive arrangement, which may be less than the original contract specified. “It’s not ideal, but it’s better than not getting paid,” a representative told me.

That was the experience of Jerry Prosser, whose 1992 graphic novel “Aliens: Hive” was republished in early 2021 as part of a 1,000-page hardcover omnibus by Marvel, at a list price of $125. Prosser didn’t know about the republication plans until late 2020, when he learned about it by chance.

To find out what royalties he might be entitled to, “I reached out to Marvel every way I could think of and got no response,” he says. Ultimately, he received what he considered to be a suitable sum, “but they made me work for it.”

The free weekly newsletter debuts Jan. 12. Readers can subscribe now.

Prosser paid an agent a 15% commission to reach out to the company, which means “I got 15% less than I would have gotten if they just answered my emails, but without her I probably wouldn’t have gotten a nickel.” (He chose not to tell me how much he did receive.)

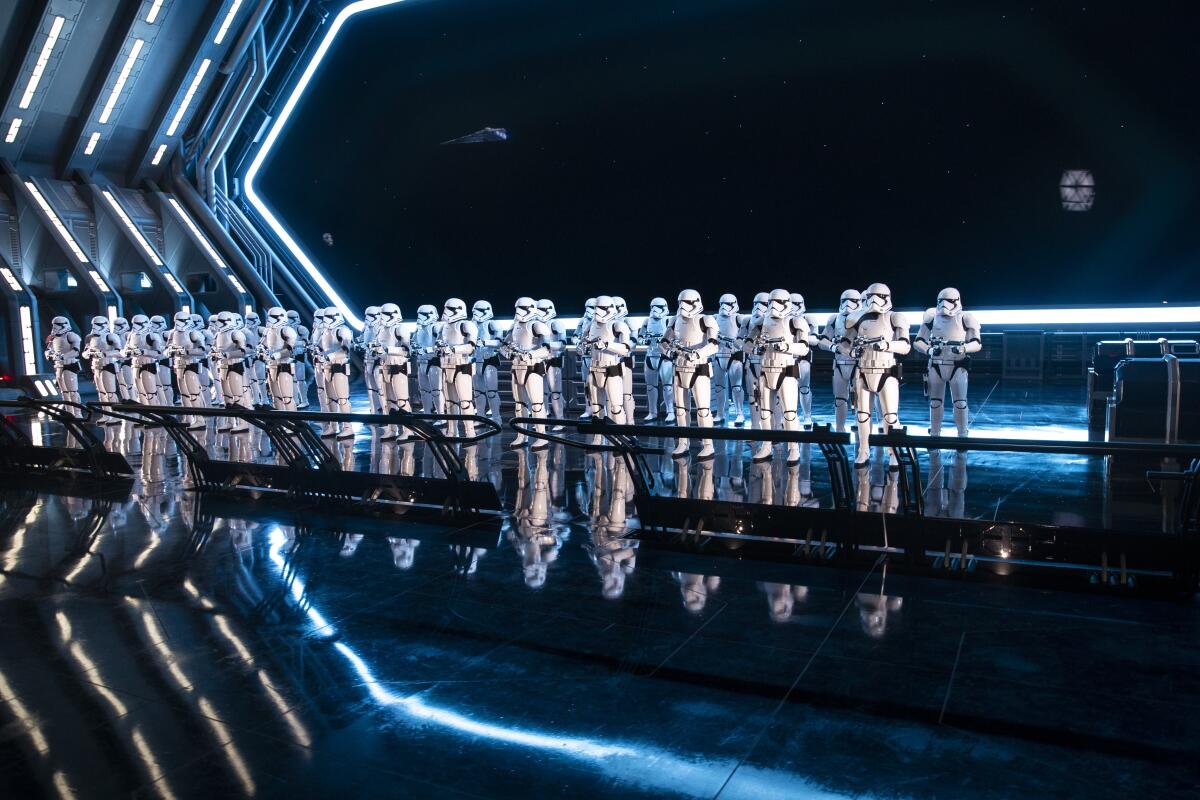

The royalty issue partially stems from the buying spree Disney embarked on starting in 2009, when it acquired Marvel Entertainment and its stable of superheroes — including Spider-Man, Iron Man and the X-Men — for $4 billion. Subsequently, Disney acquired Lucasfilm and its “Star Wars” franchise for $4.05 billion in 2012, and 20th Century Fox’s entertainment assets for $71.3 billion in 2019.

Integrating all those companies has been a complex task due to the multiplicity of corporate records and payment systems.

Some artists and writers may have fallen victim to peculiarities in entertainment contracts. For example, royalty responsibilities in the comic book industry may not be as clear-cut as in book publishing.

That may be the case with some of the material republished by Boom Studios, an independent publisher in which Disney inherited a minority stake when it acquired Fox, which made the original investment. Dark Horse Comics published graphic novelizations of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and other properties on license from Fox, which subsequently relicensed the novelizations to Boom.

“Boom did not get it contingent on making any payments to anyone else,” says Boom board member Paul Levitz, a former president and publisher of DC Comics.

Levitz says Boom has volunteered to make royalty payments based on its own contract standards.

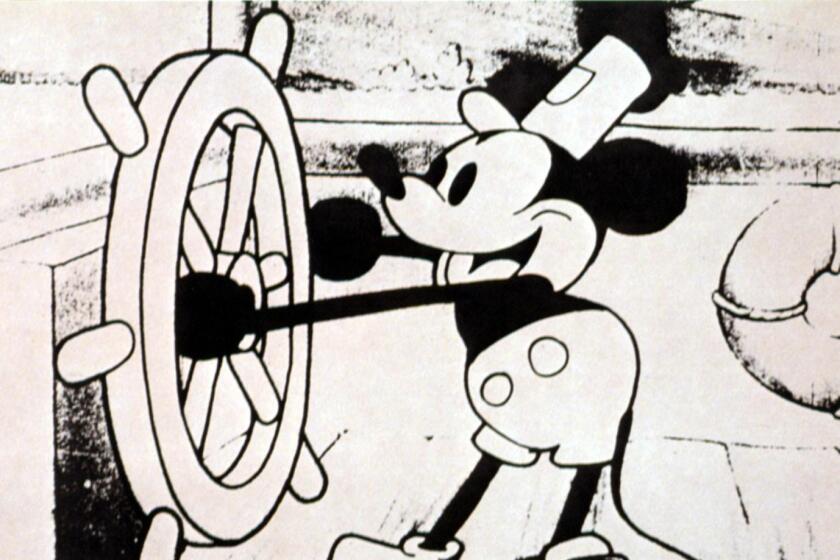

Disney’s copyright protection for the 1928 version of Mickey Mouse will expire in 2024, and Republicans want to make sure of it. Does it matter?

Agents say those contracts set a sales floor of 10,000 copies before royalties kick in, a level that is unlikely to be met for properties associated with a series that largely ran out its string in the early 2000s. In any event, representatives for writers and artists say no one has received payments from Boom on those terms.

Many of the works were originally contracted as “works for hire,” meaning that the copyrights are not owned by the authors or illustrators, but by the original contracting entity, such as Lucasfilm or Fox, and have therefore been transferred to Disney. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that the creators aren’t due royalties when the works are republished.

“These franchises are ongoing, so these books will stay in print basically forever,” says Michael Capobianco, a former SFWA president whose late wife Ann Crispin wrote three books telling the life story of Han Solo prior to his appearance in the first “Star Wars” movie, for which Crispin’s estate says royalties are due and unpaid.

“These books have slow but steady sales,” Capobianco says. Crispin, who died in 2013, wrote as A.C. Crispin.

The task force suspects that Disney is exploiting the confusion to leave creative artists out in the cold.

‘Winnie-the-Pooh,’ ‘The Sun Also Rises’ and many other works entered the public domain on Saturday. They show what’s wrong with the system.

Kowal and others say that Disney has refused to take a proactive approach to identifying the creative artists who are owed money and paying what it owes. The company has ignored pleas by the task force and individual agents to post a portal on its website and a FAQ page to inform writers how to file claims and to whom their claims should be addressed.

The company has also refused to accept names and contact information from the SFWA for writers and artists who have reached out to the organization. “Disney gets away with this by using the exhaustion tactic,” Kowal told me. “They wear people down.”

The tactic works, she says: “Some authors have just given up because Disney puts up roadblocks and makes people jump through hurdles.”

The company, according to Kowal, has told some authors who stopped receiving royalties or royalty statements that this happened because it didn’t have their addresses. “They tell that to authors they’ve sent author copies of books to,” Kowal says, “so clearly they have their mailing addresses.”

Some of the problem is due to “misorganization and miscommunication,” says Alice Speilburg, a literary agent representing about a dozen creators seeking payment from Disney. “But there’s also pushback. It’s too much trouble [for Disney] to find all these authors. So although they know this is happening, they’re not taking the initiative to put these authors in the system.”

The sequence of licensing and relicensing, she says, has produced a “no man’s land where no one is taking credit for being the person who has to pay the writer.”

Disney’s failure — or refusal — to proactively resolve its creators’ royalty claims should concern every creative artist.

“Disney’s argument is that they have purchased the rights but not the obligations of the contract,” Kowal said at a 2020 news conference about Foster’s situation. “If we let this stand, it could set a precedent to fundamentally alter the way copyright and contract operate in the United States. All a publisher would have to do to break a contract would be to sell it to a sibling company.”

At the same event, Foster himself evoked Walt Disney’s memory in appealing to the company. “I’ve always loved Disney,” he said. “I don’t think Uncle Walt would approve of how you’re currently treating me.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.