By exploring L.A.’s racial injustice, Luis Valdez’s ‘Zoot Suit’ gave birth to Chicano theater

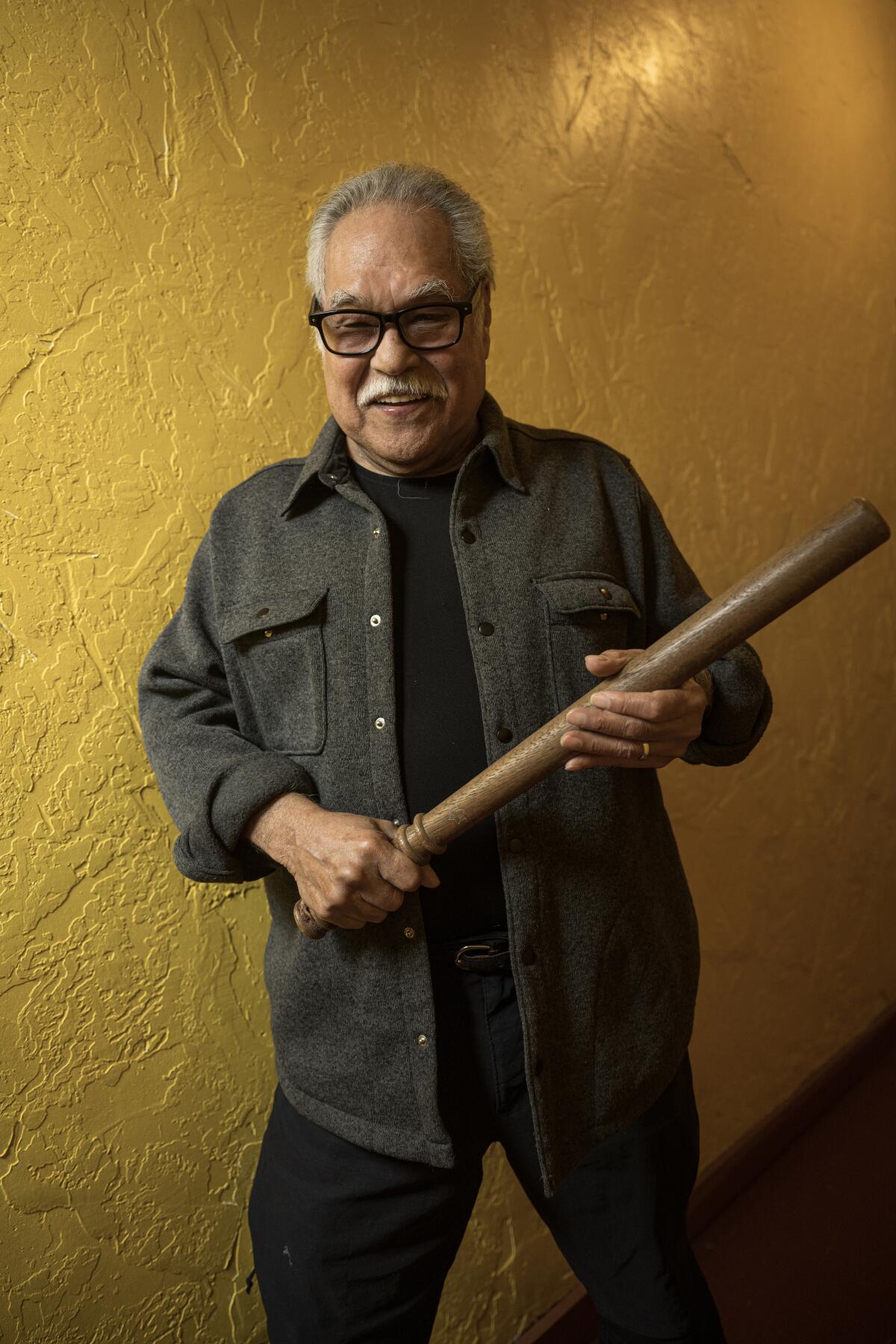

SAN JUAN BAUTISTA, Calif. — Eyes defiant, chest out, right hip cocked like a switchblade, Luis Valdez is channeling his inner Jaguar.

He’s demonstrating the El Pachuco stance, the provocative hep-cat pose immortalized by Edward James Olmos when he created the hypnotic and seductive main character who struts and glides across Valdez’s era-defining 1978 play “Zoot Suit.”

Inspired by a pamphlet about the Sleepy Lagoon murder case and the riots that it sparked, which Valdez kept in his back pocket for a decade, “Zoot Suit” was seen on stage by hundreds of thousands in Los Angeles, New York, Mexico City and South America, and by millions more in the 1981 film version that Valdez directed. Forty-five years after its premiere at L.A.’s Mark Taper Forum, it remains by far the most influential play by a Chicano author and the only one ever to reach Broadway.

As L.A. readies this month to mark the riots’ 80th anniversary, many will remember and interpret that spasm of bigotry and brutality through the prism of Valdez’s play, which expanded and permanently altered the city’s historical memory of that event. And El Pachuco, in his high-waisted “drapes” and angled hat, who narrates “Zoot Suit” while occasionally stepping outside the Brechtian fourth wall to freeze-frame the action or utter caustic commentary, is its righteously insolent heart.

“It’s the warrior stance, really,” Valdez says, modeling El Pachuco’s isometric aesthetic for a photographer. “It’s in the legs. It’s called the Jaguar, because it’s getting ready to pounce, if you have to. And yet be cool, right?”

On an early spring day, Valdez is kicking it at the headquarters of El Teatro Campesino, the irreverent performance troupe that he and a scrappy group of Mexican American field hands dreamed into being out of the social turbulence of the 1960s. The Central Valley fields, where Valdez labored as a boy, the second of 10 children in an itinerant farmworker family, are ablaze with colors that Mondrian would’ve coveted.

Valdez conceived El Pachuco as the embodiment of the outrageously stylish young batos he used to spot around town, who spoke a Cantinflas-meets-Raymond-Chandler patois called caló and jitterbugged at clubs from Boyle Heights to Bakersfield. On a June night in 1943 Los Angeles, a group of them were set upon by marauding U.S. sailors and racist mobs, bringing panic to the streets

Another 80 years passed before the L.A. County Board of Supervisors, would vote unanimously, last month, to condemn the brutal attacks on Latino, African American and Filipino youths as “one of Los Angeles’ most shameful moments in history.”

By elevating what had been a semi-obscure chapter of regional history, “Zoot Suit” stamped the ’43 riots as part of a continuum of Latino political consciousness that prefigured the 1970 Chicano Moratorium, a watershed event akin to Selma ’65 or Stonewall ’69.

“Zoot Suit” also made an overnight star of Olmos and boosted the careers of several other cast members. After selling out its extended run at the Taper, it took up an even longer residence at the Aquarius Theatre on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, en route to the 1,500-seat Winter Garden in Manhattan, where the tribal New York critics were confused and hostile but the mixed-ethnic audiences gave standing ovations.

The untold story of the Zoot Suit Riots: How Black L.A. defended Mexican Americans

“It was a monumental moment in time, and we captured lightning in a bottle,” says Olmos, speaking by Zoom and reeling off his bilingual opening monologue from memory. “Not only did it change the course of Latinos in theater but it touched the very soul of the culture. It was catching the voice of the pachuco.”

Although “Zoot Suit” unfolds in L.A.’s urban environs, its spiritual birthplace was in this historic farming town dominated by its namesake Spanish colonial mission. El Teatro, which Valdez founded in 1965, settled here in 1971, after honing a revolutionary performance style that fused mime, commedia dell’arte, music, political satire and stylized physicality into one-act shows called “actos” that had been deployed to help organize migrant workers into the United Farm Workers union.

A compact, bright-eyed man who turns 83 later this month, Valdez has the demeanor of a warm and funny village elder who just happens to be the founding parent of Chicano theater. Still writing constantly, juggling multiple projects, he’s the bilingual, battle-tested conscience of a pivotal art and social movement. Cool, yes, but ever ready to pounce.

“It’s just unbelievable the energy this man has. It’s like 10 buffaloes,” says Demián Bichir, who saw the movie version of “Zoot Suit” while growing up in Mexico City and went on to portray El Pachuco in the 2017 revival at the Taper.

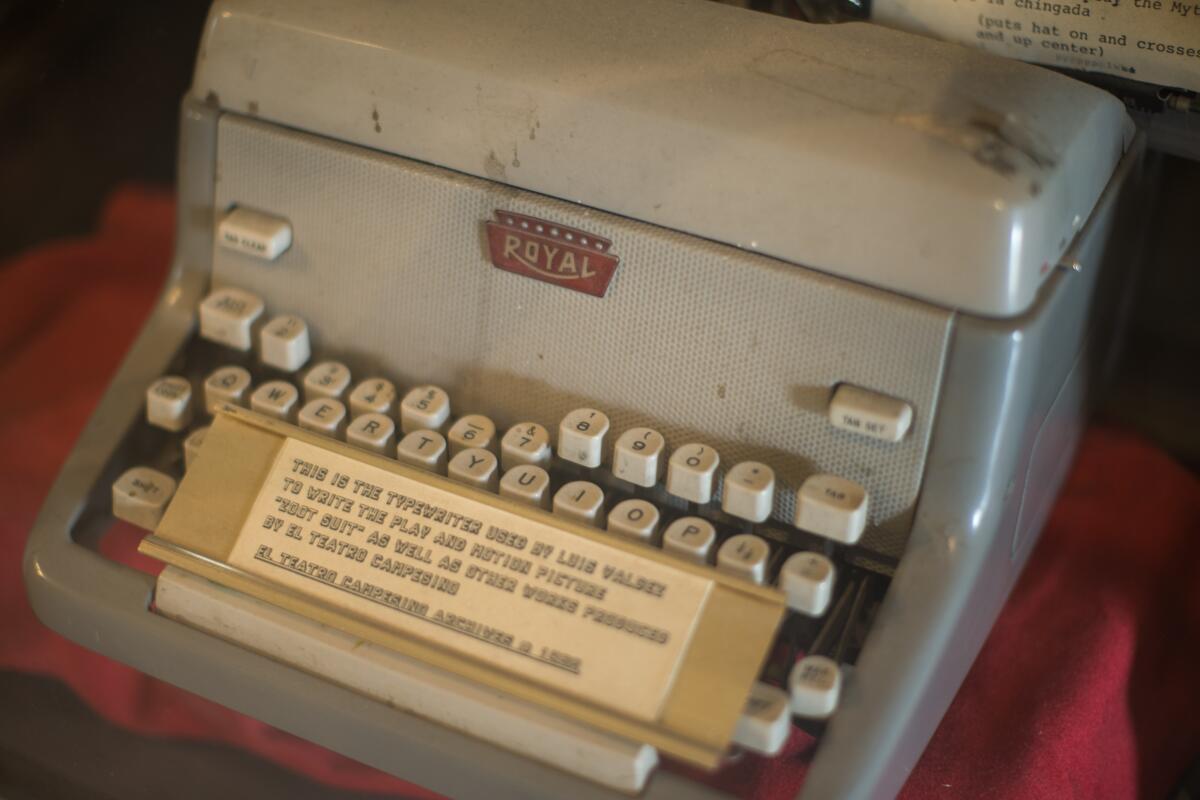

One of El Teatro’s interior walls is a kind of “Zoot Suit” stupa. A cabinet displays the Royal typewriter Valdez used to bat out his drafts. Black-and-white photos of Olmos, Lupe Ontiveros and other original cast members frame a facsimile of the Western Union telegram sent by Alice Greenfield McGrath, an activist who became the executive secretary of the Sleepy Lagoon Defense Committee.

Among the faces is that of Enrique Castillo, the stalwart El Teatro member cast as Henry Reyna, leader of the 38th Street Gang, whose members faced the gas chamber if convicted of the Sleepy Lagoon murder. Castillo says he glimpsed many aspects of his own parents in Valdez’s depiction of Henry Reyna’s family. And the attitude, body language and code-switching of the young male characters mirrored his own and that of his friends.

“I borrowed from a lot of my friends who were street savvy. A lot of them got into the kind of trouble that these guys did. I did quite a bit of it, but I never got caught!”

For its young, mostly Mexican American cast, “Zoot Suit” offered a rare opportunity both to redress a historic wrong and to check Hollywood’s myopic view of Latinos, Castillo says.

“Slowly but surely we began to see more of our peers, more Latinos, wanting to enter the industry because they had seen the show,” he continues. “Even today I still run into people now and then who say that’s how their career started, by having seen the play.”

On the opposite wall at El Teatro, posters, photographs and other archival material evoke the glory years of the Delano grape strike, testimonials to a bruised but determined people. Like Dolores Huerta and other comrades from that time, Valdez views today’s struggles as sequels to those of a half-century ago.

“My faith now is in Generation Z,” he says. “They’re the ones that have to live in tomorrow’s world. And all these old people that are corrupt, that are going to die tomorrow anyway, they’re no longer invested. It has to be the young people. Teatro Campesino was born with teenagers. I was 25 years old but other members were 18 and 19, with great energy taking on the world.”

El Teatro’s headquarters, a converted packing house, has beckoned many cultural sages and prophets to make pilgrimages here. Among them were Peter Brook of Britain’s Royal Shakespeare Company, and Gordon Davidson, founding artistic director of L.A.’s Center Theatre Group, who commissioned “Zoot Suit” believing that it could help attract a younger, more diverse audience. For them, El Teatro is as much of a spiritual repository as the mission, where in Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” a wild-eyed Jimmy Stewart drags Kim Novak up a bell tower before she plunges to her death, a victim of his mad obsession to re-create the past.

This throwback town of 2,000 also is where Native Americans chafed under the rule of their Spanish overlords, and where the notorious outlaw Tiburcio Vásquez, the antihero of Valdez’s caricature-busting melodrama “Bandido!” became one of the last men in the United States to be hanged in public. Nearby the San Andreas fault bulges up out of the fields where new generations of migrants toil. Like the mission, El Teatro has survived many tremors, including a leaky roof, periodic funding challenges and the COVID pandemic, which forced the company to shut down for a spell.

It was in seemingly placid landscapes like this, wrought in violence and pregnant with contested meanings, that Valdez encountered his first pachucos. “It impressed me, just as a child,” he recalls. “I said, ‘Oh, these are curious beings, very strangely dressed!’”

Among them were his beloved cousin Billy Miranda, who mimicked the Spanglish-spouting Mexican comic Tin-Tan and was stabbed to death in 1955 — “17 knife wounds to the chest,” Valdez says. There also was a friend of Billy’s, a mysterious pachuco from Delano known as “CC,” who one day in the mid-1940s had the temerity to sit in the white-folks section of the Delano Theater. An usher asked him to move, but CC, a Navy veteran, wouldn’t budge. Eventually the cops came and hauled him away for a two-hour grilling before releasing him, Valdez says. But other pachucos saw that CC had gotten away with something. So they followed his example and began to sit wherever they pleased.

About two decades later, when Valdez was traveling back to Delano to join the grape strike, his mother asked if he was going to work with CC.

“And I said, ‘CC, is that vato still around?’ And she laughed and she said, ‘Mijo, don’t you know who CC is? He’s Cesar Chavez.’”

If there’s a touch of Cesar Chavez in El Pachuco, the character’s mythic presence, his stylized menace and insinuating mannerisms tap into an even deeper mythos, dating back centuries. Valdez first used the character of a zoot suiter to represent La Luna, the Moon, in his allegorical play “Bernabé.” Both La Luna and El Pachuco evince his fascination with pre-Columbian art, the prints of José Guadalupe Posada, the murals of Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, and the cultural insurrection of the Mexican Revolution of 1910-20.

“I knew that really what I was evoking with the Pachuco was one of the gods of the Aztec pantheon,” Valdez explains. “It was called Tezcatlipoca — the Jaguar Knight, the Jaguar’s Son Who Rules at Night. And so the Pachuco was a creature of night, so to speak. That suit was not for broad daylight or early in the morning. It’s really for night — the urban night, on top of that, under streetlamps. Eddie encapsulates it. He is the jaguar. That’s his power.”

An indelible throughline links El Pachuco to the Jaguar Knight; the Central Valley farmworker to the urban Chicano; El Teatro Campesino to the Mark Taper Forum; and “Zoot Suit” to all of it.

Indeed, one could imagine “Zoot Suit” as Act 1 of an El Teatro epic akin to Peter Brooks’ nine-hour 1985 stage production of the Hindu saga “Mahābhārata,” a masterwork enfolding the 1943 Zoot Suit riots, the bracero program, the Japanese American concentration camps (which is the setting for Valdez’s “Valley of the Heart”) and the 1992 L.A. uprising. The extravaganza could be topped with a commedia dell’arte epilogue, in which a red-tied harlequin with orange skin and a floppy comb-over takes a pratfall off The Wall, while the Spirit of Ricardo Flores Magón (played by Eddie Olmos) floats by muttering, “Well, I warned you about building fences, pendejo.”

But, for now at least, “Zoot Suit” alone remains the alpha and omega of Chicano theater. Valdez credits a long list of names with its ambition and endurance: The Taper’s Diane Rodriguez and Jose Delgado, who dug up books and articles to assist his research. Carey McWilliams, the prolific leftist journalist, who offered several timely and valuable suggestions during the fact-gathering phase. An ethnomusicologist who rounded up a collection of Lalo Guerrero songs, snippets of which found their way into the text. Miguel Algarín and Miguel Piñero of the Nuyorican Poets Café, which lent spiritual support to the show during its New York run. Many more names, dates and anecdotes can be found in the El Teatro collections at UC Santa Barbara and Cal State Northridge.

Is there, somewhere in those boxes, the kernel of a radical notion, a preliminary sketch for the next Chicano masterpiece awaiting birth, whether set in a Fresno field or a Downey strip mall? Valdez is hopeful that those shows are en route, and that they won’t need to follow any path but their own — certainly not that of the Great White Way (emphasis on white).

“It’s not just a question of sending the covered wagons from East to West and killing people along the way in order to settle the continent, take half of Mexico as you go,” he says.

Today, Valdez believes, the U.S. imagination is shifting West-East and South-North.

“‘Zoot Suit’ was like an early missile that came from West to East and said, ‘We’re here. Deal with us.’ And they said, ‘We don’t want to deal with you. Not yet.’ And I said, ‘OK. We’ll be back.’ And there’ll be other works that are coming.”

As the Jaguar Knight looks on, flashing his fierce, enigmatic smile.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.