Column: The real reason AMC just raised prices for ‘better’ seats

I don’t have a business degree, but it seems to me that if movie exhibitors want people to leave the comfort of their streaming-serviced homes for the pleasures of the multiplex, raising the price of the seats most people prefer is probably not the best move.

And yet that is what AMC has chosen to do, announcing on Monday that it will soon be offering “Sightline” tiered pricing.

Seats close to the aisles will remain at “standard” pricing, which in the Los Angeles area range from $14 to $18 for adults attending a nonmatinee showing, but for AMC Stubs members (including those with free “Insider” status) there will be a discount for those willing and able to sit in the front row without getting motion sickness or neck issues.

The big change, however, is a bump in prices for “preferred” seating, i.e. the mid-row, mid-theater seats that usually get filled in the fastest. (The exact amount of the increase has not been announced, but people on social media who claim to have visited test theaters put it at a buck.)

Only members of the $20 to $25 a month Stubs A-list membership will be exempt from the higher prices, a fact that reveals one very big reason why AMC is doing this: to offer yet another reason why theatergoers should become, essentially, AMC subscribers.

The chain’s press release, like many documents of its kind, is rife with corporate-speak fast-talking, much of it contributed by Eliot Hamlisch, the chain’s executive vice president and chief marketing officer, who claims that by “offering experience-based pricing” the chain is actually helping to “ensure that our guests have more control” over their moviegoing. (Strangely, no tier is available to those who want to avoid the sound of a cellphone ringing or people talking, which is the only experience control most of us want.)

AMC Theaters introduced a new program of pricing based on seating location, with lower-price front row seats. Seats in the middle will cost more, the company said.

What is in fact perfectly clear is that even Nicole Kidman extolling the wonders of the theatrical experience in her spangly pantsuit was not quite enough to boost profits. AMC’s line of “Heartbreak feels good in a place like this” merch, just in time for Valentine’s Day, hasn’t helped either.

Equally boneheaded: turning one of the last bastions of egalitarianism into yet another VIP-worshipping, comfort-plus upselling economic hierarchy.

As consumers grow increasingly outraged at airlines that charge extra for everything but oxygen and Airbnb faces complaints about hosts who practically charge 2% for looking in the mirror twice, it seems a less than felicitous moment for a business already plagued by empty seats to make many of those seats more expensive.

While it is sadly true that far too many people are willing to pay more for the addition of the word “preferred,” I don’t think the competitively consumptive are AMC’s target audience; most of us are still irritated by those online reservation service charges.

As may be obvious by my crankiness, I am old enough to remember when the only way to guarantee getting a good seat at the movies was to show up early and pray that a really tall person — or someone wearing a hat — did not sit in front of you. (Memo to guys currently sporting fedoras: If you’re going to wear your grandfather’s hat, follow your grandfather’s rules and take it off indoors.)

I am also mercifully uninterested in middle seating; after far too many years of shepherding large groups of children to the movies, I always choose the aisle for easy access to the restroom.

But here’s where I admit my hypocrisy — which is more to the real point of all this upcharging. I am an AMC Stubs A-list member, which means that by paying $25 a month, I get three movies a week, in any theater, including the fancy ones with reclining seats, and in any format, including Imax, as well as a bunch of other perks.

AMC’s A-list is what this change is all about: not making more money off ticket sales, but pushing more people to join the chain’s paid membership base.

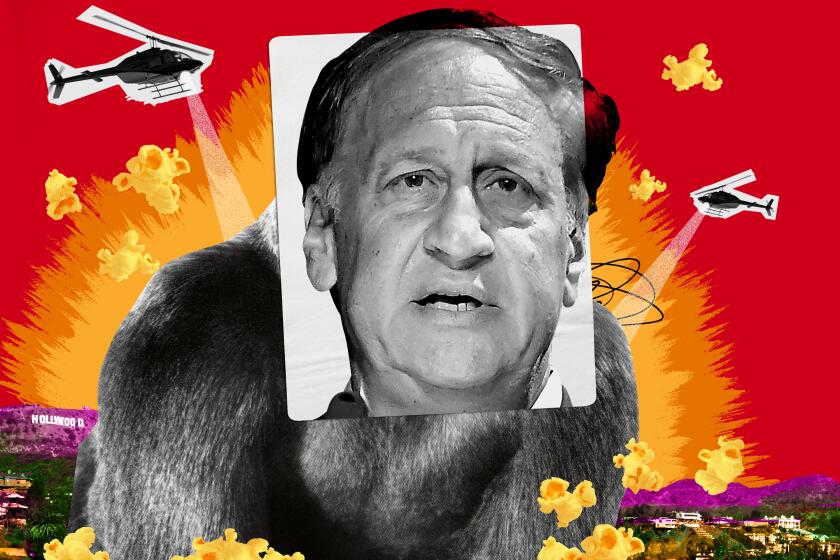

Adam Aron rode the meme stock wave to rescue AMC. With his embrace of NFTs and cryptocurrency, plus a campy Nicole Kidman ad, he’s a polarizing figure.

I mean, if you can get three movies a week for just a few dollars more than you would have to spend on a single showing in the seats you like, why wouldn’t you?

Well, there are loads of reasons, including the fact that if you have a family, $25 a month can easily become $100 or more. Also, having already spent the equivalent of almost two movies at AMC, you will feel obligated to get your money’s worth by seeing at least two movies a month at AMC.

That’s the point, of course. But getting more people into the theaters isn’t about the tickets or the catharsis of cinematic heartbreak; it’s about the popcorn. And the soda, the hot dogs/cheesy nachos/mini-pizzas. Raising the ticket prices won’t help the bottom line much because tickets have never been the money-maker; concessions are.

No doubt there are people who can go to the movies and not buy popcorn, soda or snacks, but I am not one of them. Especially when I tell myself how much money I am saving with my nifty-swifty membership.

Still, for someone who likes going to the movies and lives a short distance away from four AMC theaters, a subscription makes sense. Except when I want to see movies that are not showing at AMC. Or patronize other theaters I do not want to close. Or go out with nonmembers who prefer other venues, including those with their own subscriptions.

Regal, Cinemark and even Alamo Drafthouse all offer a paid memberships with varying price points and perks, which they urge moviegoers to join through onscreen advertisements before every show. Of these, AMC’s A-list is generally considered the best value; the new Sightline price changes make it even more so.

The membership model is relatively new for movie chains, replacing the short-lived MoviePass with a system that can actually save you a lot of money.

Though if we look to streaming services as a predictor, these memberships may well increase in price — and potentially decrease in value.

The plan, which starts Nov. 3, would bring 4 to 5 minutes of commercials per hour to Netflix programs like “Emily in Paris.”

Which brings us to the larger issue already bedeviling streamers: How many subscriptions can dance on the head of a PIN?

How big a portion of our lives are we willing to turn over to a monthly fee and a bar code?

I say subscription and AMC says membership; I suppose that once upon a time there was a difference. Subscribers to newspapers, magazines, newsletters and even various thing-of-the-month clubs got what they paid for, delivered to their homes, whether they used them or not.

Memberships, on the other hand, guaranteed entry to venues, including museums, gyms and clubs, based on a business model of under-use. If everyone who belonged to a gym used the facilities for several hours every day, most gyms would go out of business.

Streaming services blurred the line between these two things: The content is available 24/7 in our homes, but action (i.e. turning on the screen) is required to get it, and sometimes too many users can cause a site to crash.

Streamers are also now offering tiered subscriptions based on the presence of ads or value-added content or services.

So when AMC says it is simply modeling a trend to “experience-tiered” pricing, it is not wrong. Live performances have always based pricing on sightlines (with a premium on proximity to the stage) and now even the entertainment content available in our own homes comes with a welter of rates and price points.

After more than a year, my husband and I have a movie date (“Together Together”) and it was very weird and extremely wonderful.

But adding movie theaters to an already chaotic consumer space prompts the question: At what point will the average person become, literally, over-subscribed?

So much of Hollywood’s mythology is based on the notion that movie theaters are magical spaces that level every playing field — together in the dark, we all share a communal and equal experience, no membership required.

Less philosophically, it’s been decades since most people centered their moviegoing life on one theater, or even one multiplex, especially in Los Angeles; unless you can afford multiple theater memberships, paid-for loyalty plans are, by definition and intent, limiting.

Even as I write this, I realize that the romanticized vision of folks strolling up to a box office to buy a ticket for a movie that starts in a few minutes is a thing of the past, like comfortable coach seating on airplanes. I very much want movie theaters to remain plentiful and profitable. Perhaps membership plans will indeed help more theaters remain open, which would be a very good thing. But making nonmembers’ lives a little more complicated and expensive is not the answer.

Maybe the next Nicole Kidman promo should tout the magic of “belonging” to the movies. “Membership feels good in a place like this.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.