Review: The L.A. Philharmonic protests. Who’s listening?

On the eve of an election day when housing happened to be a major ballot issue, it was not easy to get to Walt Disney Concert Hall, where the Los Angeles Philharmonic was staging a new gentrification oratorio, Ted Hearne’s “Place,” as the concluding concert to its “Power to the People!” festival. Streets were closed and freeways exits blocked. Gridlock generated road rage as world leaders and their cohorts of diplomats traveling in heavily policed caravans began taking over downtown L.A. Tuesday for their Summit of the Americas the next day.

There goes the neighborhood.

We were, however, warned. In a wide-ranging discussion about art, race and social justice at Disney two nights earlier, the activist scholars Angela Davis and Bryonn Bain credited artists and abolitionists as seeing what is not yet there.

Indeed, “Power to the People!” — co-curated by music and artistic director Gustavo Dudamel and creative chair for jazz Herbie Hancock, both of whom have been dedicated to applying music toward the cause of social change throughout their careers — could not have been more prescient when the L.A. Phil originally mounted it in 2020. The pandemic then shut it down midfestival, and Davis’ talk was the first program to be canceled. Two months later, an epic protest movement shook the nation following the murder of George Floyd, leading to a profound national reawakening about civil rights.

While very little of what the orchestra had planned over its long, dark pandemic months could, or needed to, be brought back, “Power to the People!” remained at the top of the L.A. Phil‘s priority list. It was a politically provocative concept for a major American symphony orchestra then. It remains so even now. Discussions of race, inclusion and social justice have become more commonplace in arts institutions everywhere. But Davis pointed out that the real social justice requires more than a wake-up call and protests; the real work must be ongoing. Consequently, the “Power to the People!” redux became somewhat less about polemic this time around and more about the sustaining social value of music.

That made the festival, perhaps, less striking and more quotidian. It was shoehorned into a host of season-ending L.A. Phil activities that included a gala 100th anniversary program at the Hollywood Bowl on June 3 and hosting the annual meeting of League of American Orchestras, all of which kept Dudamel and the orchestra exceptionally busy. That also meant that individual “Power to the People” events tended to attract different, and primarily partisan, audiences.

Yet on the macro level, the L.A. Phil has bounced back from the pandemic with greater investment than ever toward making the symphony orchestra — that supposedly musty, elitist constitution of subservient musicians playing in military lockstep in an effort to enhance the power of the ruling class — an empowering voice of the people. Day after day, there has been a dizzyingly democratic, and often brilliantly realized, stream of new work, reimagined old work and inclusive work unlike that found in any other major arts institution in America or beyond.

Freedom and unity has been a broad theme over the last two months, highlighted by Beethoven’s two great hymns of liberation — his prison opera “Fidelio,” revelatory in its staging with Deaf West Theatre, and the Ninth Symphony given Dudamel’s grandly spiritual yet impatiently exuberant performance. Thomas Adès’ new ballet, “Dante,” proved a goofy yet transformative guide for liberation from worldly anxieties.

Thomas Adès curated the L.A. Phil’s Gen X festival, a celebration of visionaries from that generation. A highlight: his orchestral “Dante.”

In a musical summit of the Americas, Dudamel matched Stravinsky ballets with classic 20th century Latin scores and newly commissioned works by Latin American composers. Every Dudamel concert in Disney this spring — with the exception of “Fidelio” and his program with the rapper, Nas — has included the premiere of at least one new work by a Latino composer commissioned for the occasion. They have been mostly short, vibrant curtain raisers in different styles. The most notable, though, was a full-scale violin concerto by Gabriela Ortiz that will be repeated in the fall, when Dudamel begins the new season with a Pan-American Music Initiative.

The Bowl gala, which attracted a huge crowd thanks to the appearance of Gwen Stefani on June 3, ostensibly steered clear of politics. It opened with John Williams conducting the premiere of his “Centennial Overture,” less fanfare than compellingly complex and chromatic pondering of the Bowl’s convoluted history by a beloved 90-year-old composer who is a living and lasting part of that history. Yet America’s most musically progressive and politically daring orchestra also even-handedly hosted the surprise appearance of Stefani’s husband, country singer Blake Shelton, who has drawn controversy for tweets from the other side of the aisle.

The Hollywood Bowl is celebrating its centennial. Learn about its history with the L.A. Philharmonic and the Beatles, Janis Joplin and more.

Does music, then, bring us together or call us to action? Obviously it does both, and the contradictory ways in which it operates has much to say about humanity and society. When asked by Bain about the opposition between formalist art for art’s sake, coupled with the suggestion that Disney Hall might be seen to represent and art that stands for a movement, Davis resisted the distinction.

“All art has form,” she replied. “All art has content.” For her, art can do something that neither scholarship nor political leaders can, which is awaken the senses. “Art is important for social change,” she insisted, “because it is the artist who can help us feel.”

That might have been the motto for Dudamel’s main “Power to the People!” program, which didn’t really have a theme. It began with the premiere of Angélica Negrón’s “Moriviví,” the Puerto Rican term for the sensitive Mimosa pudica plant that closes its leaves when touched. The score begins with bright but elusive plucked sounds of harp and strings, as though the musician’s hands were delightedly glancing pliant pudica foliage. Melody enters slowly with hints of dance rhythms that fade, more to be remembered than heard, the dying and living of sound to mirror what it feels like to touch and thus activate a moriviví leaf.

Peter Lieberson’s “Neruda Songs,” which the L.A. Phil premiered in 2005, rely on the Chilean poet’s sensation of love that is feeling of something that exists in a metaphysical realm beyond physical touch. It was written for the composer’s terminally ill wife, mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, who died a year later. J’Nai Bridges sang it with more conventional sentiment than had the fearlessly penetrating Hunt Lieberson, as love in the here and now and not in the eternal beyond.

For the one major orchestral work of the festival, Dudamel revived William Grant Still’s “Afro-American” Symphony, a symphonic masterpiece from the Harlem Renaissance written in 1930. It was played often in the 1930s and first reached the L.A. Phil in 1940, by which time Still had moved to L.A.

The symphony exemplified exactly what Davis meant by putting rich content, including blues and spirituals, in a luminous form. Dudamel’s performance brought out the symphony’s intensity in what felt like a revolutionary power-to-the people way. It was good to have had, thanks to the League’s gathering, hundreds of American orchestra representatives in the audience. Let a Still renaissance begin.

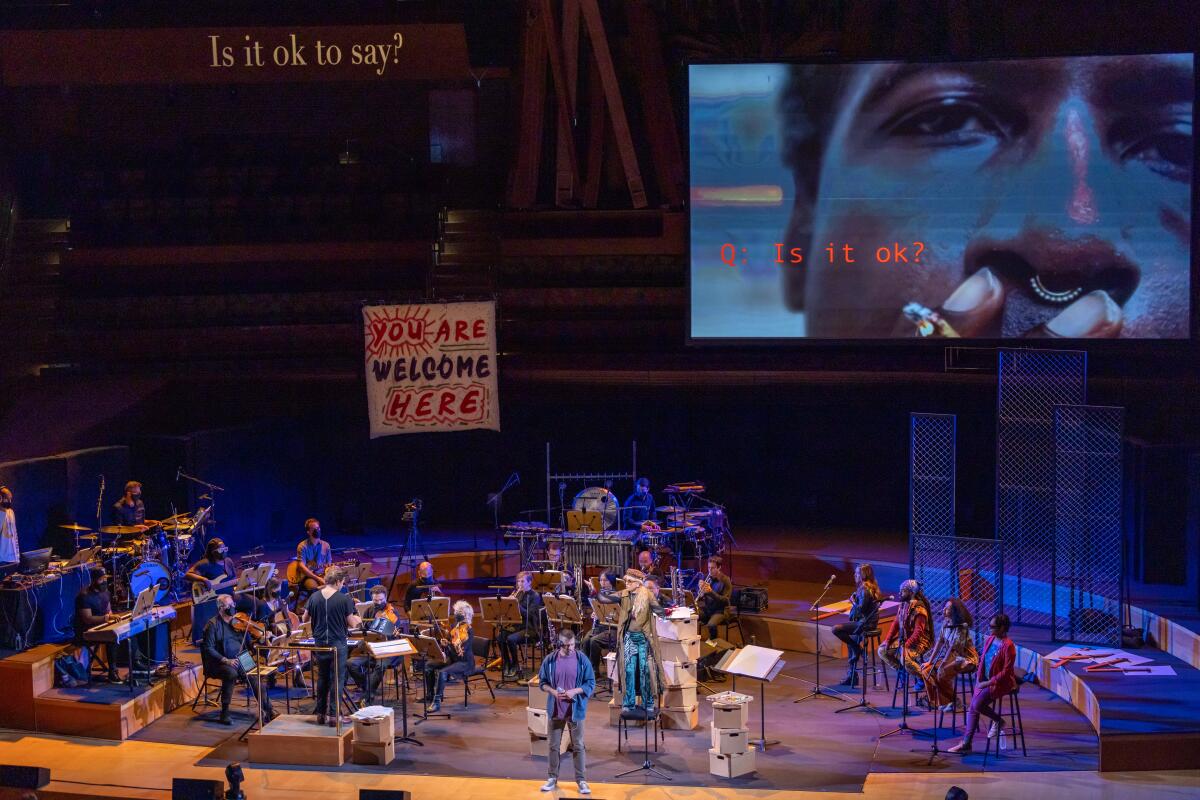

With “Place,” the premiere of which was supposed to have been given during lockdown, outright agitprop finally found a place in the festival Tuesday. Hearne calls it an oratorio, but it operates more like a song cycle with 19 numbers. The texts are by the composer and poet Saul Williams. As staged by Patricia McGregor, the oratorio implied raw and rich street life. The six singers were a mix of pop and classically trained. The same goes with the use of pop musicians and members of the L.A. Phil New Music Group. The composer conducted.

In the first Hearne-centered part, the composer, meditating on his young, sleeping son, tries to find his place in the larger place in a trouble society. He turns to James Baldwin and other writers for help. For the second part, Williams challenges Hearne’s and white society’s many assumptions. The poet’s anger explodes, while finding unexpected beauty in tongue-tied humor and sarcasm. The eighth number, “Hallelujah in White,” is nothing more than the line “Mind your business,” repeated over and over to the “Hallelujah” Chorus from Handel’s “Messiah.”

Yet “Place” ends in stunning rhapsody. Hearne’s place and Williams’ place meet in a vast universe capable of Neruda-level love.

Hearne’s score grates, agitates and seeks sweetness. Gentrification is not addressed as a situation as much as a state of mind. Instead of being an argument about greedy developers and disingenuous politicians taking over the neighborhood, Hearne and Williams take over the senses. Rather than being art about what to feel, “Place” seeks a place for art that demonstrates how to feel so you can then better know how to act.

It would be nice to think that the politicians, ill-prepared to awaken senses in their security bubbles at the ninth Summit of the Americas a mile down blockaded and well-armed roads at the convention center, might could somehow acquire a clue as to the place where they happened to be. They might better know how to act before beginning their well-orchestrated wheeling and dealing.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.