Commentary: As the L.A. Phil prepares for Power to the People! festival, Ives sets the stage

For the 1912 election between Democrat Woodrow Wilson, Progressive Theodore Roosevelt and Republican incumbent William Howard Taft, Charles Ives wrote a song for high tenor and three pianos, “Vote for Names! Names! Names!” One piano incessantly bangs out the same dissonant chord, while the other two pianos repeat hollow phrases. These represent the candidates, each with his “hot air slogan.”

The singer is the disillusioned voter who can’t figure out the best way to vote. “I say,” the tenor announces, “just walk right in and grab a ballot with eyes shut, and walk right out again!”

Little has changed 108 years later. It wasn’t quite so easy to walk right into many overcrowded L.A. polling places, and the trend is toward ballots not being something you actually can grab. Still, with each political season, Ives becomes ever more instructive, and whether or not intentional, the Los Angeles Philharmonic happens to be startlingly on the case.

After conducting a rare cycle of Ives’ four symphonies, Gustavo Dudamel now begins the orchestra’s audacious Power to the People! festival, which he is co-curating with Herbie Hancock. Over the next month, the L.A. Phil will spotlight protest art, or at least the subject of the people’s will. You can even register to vote at a concert in Walt Disney Concert Hall.

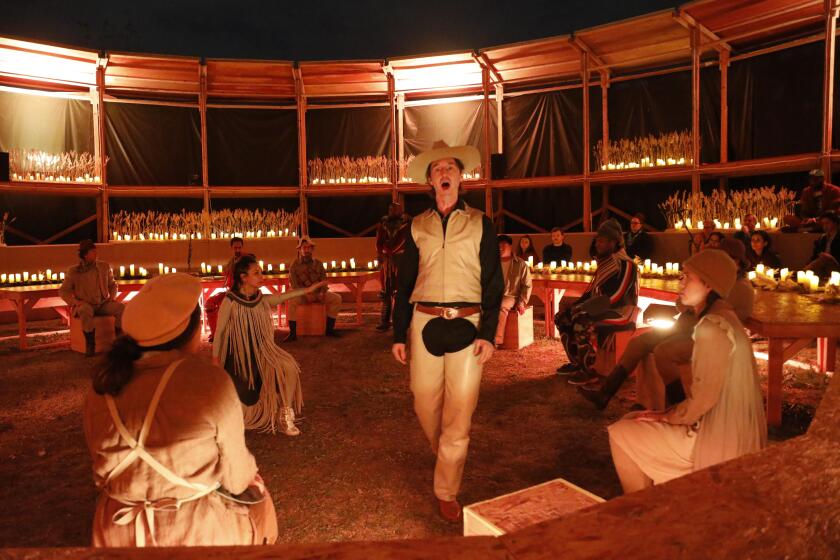

Opera phenom Yuval Sharon, Native artists Cannupa Hanska Luger and Raven Chacon, and Chinese-born composer Du Yun deliver a gloriously ambitious show.

Ives can be seen as a composer who helped set the stage for what became the 1960s protest movements, which had a great influence on Hancock. Dudamel is living through the political horror of his native Venezuela, where he cannot return after expressing his support for peaceful protest.

Perhaps that played into the extraordinary conviction he brought to the Ives symphonies. His performances were joyous, spiritual, powerful, adventurousness, wrenchingly emotional and inspirational. He made the symphonies represent divisive current issues in a far greater complexity than we get in our normal public discourse. And in so doing, Dudamel couldn’t help but make Ives more meaningfully mystifying.

The first great American composer, Ives was in the early years of the 20th century the most avant-garde composer on the planet, and he remains startlingly challenging a century later. There is perhaps no greater exercise in thinking about America than in trying to come to terms with Ives — his music, who he was and what he represented.

Ives could have been a professional baseball player, so great was his talent in college. He might have become the greatest organist of his time, so great was that talent. He made a fortune as one of the founders of the insurance business in New York, yet he undoubtedly would be a Bernie man today, supporting Medicare for all and breaking up Wall Street.

Full of paradoxes, Ives was also MAGA all the way, a stubborn Connecticut Yankee who strove to sustain the sweet all-American innocence of his small-town youth in Danbury. He created the most outrageous music full of daring dissonances, music in which conflicting rhythms were all heard at the same time, music that gave regular harmonic raspberries to tradition. But all of that was in service of reminding us of what had once made America great.

That greatness for Ives was independence of thought and being. He was an authentic populist who financed a campaign in 1920 for a constitutional amendment to get rid of the electoral college. In his feisty populism and uncompromising high-mindedness, he was, as the musicologist Judith Tick has called him, a transcendental majoritarian.

Dudamel captured that brilliantly last Friday. The audience laughed when Dudamel began by conducting Ives’ “The Unanswered Question” on a stage with no orchestra. A solo trumpet posed its unanswerable question of existence in a short melodic figure far off in the distance, while somewhere in the wings chirping winds pondered that and string murmured mystically. The ethereal nature of existence was made necessarily ethereal.

Then the stage filled up massively for the Fourth Symphony, arguably Ives’ most important work. It was begun in 1910, two years after “The Unanswered Question.” It begins with a hymn. It has a revolutionary collage movement full of American tunes, hymn tunes, Beethoven and whatnot, jumbled together as no music had ever been jumbled together before. There is then a big orchestral fugue and finally a transcendental dissonant finale.

The orchestra is gigantic and includes keyboards of all sorts (with pianos tuned a quarter tone apart), a substantial percussion section and a chorus (the Los Angeles Master Chorale). Two conductors are needed, and Dudamel Fellow Marta Gardolinska conducted a “distant” ensemble, beating meters and tempos different from Dudamel’s. Usually the second conductor in this piece stands apart, barely noticed. Dudamel placed Gardolinska right next to him, and she was noticed. Already beginning to make a splash in Europe, she is ready for more.

In a performance of extreme clarity and authority, Dudamel offered a vision of an America vast and sure and true and just and progressive and trusting, a land of the free and the caring in what sounded convincingly to be the Great American Symphony.

It took a decade after Ives’ death in 1954 for his music to be widely heard, and that revival helped empower the music of the 1960s power-to-the-people movements in many ways. An ensemble, Tone Roads, named after an Ives score, promoted the early minimalists and the latest American experimentalist. Hippies dressed in American flags embraced Ives’ Americana, a return to American ideals.

But Ives’ world had not been this world. He was a progressive artistically but not socially. He exhibited homophobia when he said tame institutional music was sissy effeminate. As a boy in late-19th century Danbury, he had been called a sissy because he was a classical musician, and he never got over it.

This led to at least a partial rejection of Ives. At a festival in Berlin on the 50th anniversary of the composer’s death, Ives was mostly heralded as a still-inspiring eccentric revolutionary, but the left-wing American composer and pianist Frederic Rzewski did not agree. He preferred Shostakovich.

It is now the 45th anniversary of Rzewski’s most famous work, the hour-long set of variations on the Chilean protest song, “The People United Will Never Be Defeated!” which Conrad Tao will play next week as part of Power to the People! Tuesday night, however, for his Piano Spheres debut at Zipper Hall in L.A., Thomas Kotcheff gave a dazzling performance of Rzewski’s recent “Songs of Insurrection.”

The 70-minute cycle of seven pieces is based on protest songs of the oppressed from America, Russia, Germany and elsewhere. Unlike the tightly knit “People United,” this is a fantastically spontaneous-sounding eruption of ever-changing keyboard invention. Rzewski puts in places for improvisation, but all of it sounds improvisational and, in its banging, creativity and insistence, a lot like the few improvisations that Ives recorded at the piano.

We can’t escape Ives. He was not of our time, and he was full of contradictions. I think Ives would agree with the sentiment of Power to the People! and yet he would like none of it (and practically nothing about our America). You can just see him updating “Names! Names! Names!” for Sanders, Biden and Trump.

But for all his blind spots and all our blind spots, Ives bravely believed in us. You don’t see that very much anymore in our divisive society, which is why we need him more than ever.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.