Column: Where is the Black public art that SoFi Stadium promised?

In a video produced by USA Today in 2011, Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones takes viewers on a tour of AT&T Stadium in Arlington, Texas, designed by the architectural firm HKS. In the nearly five-minute video, Jones hits all the top spots: the playing field, stands, club areas and, of course, the locker room. He also spends a good 30 seconds talking about something slightly unexpected: the stadium’s incredible art collection.

The camera pans past a large-scale wall painting by L.A. artist Gary Simmons that shows a field of blue explosions, and a massive, multilevel vinyl installation by German artist Franz Ackermann that adds deeply saturated swathes of color to a transitional area around an escalator. What makes the stadium unique, says Jones, “is that some people might see a piece of contemporary art by a museum-quality artist, and they might say, what’s that got to do with a tackle? What’s that got to do with a snap? Well, it’s closer than you might think. ... At the end of the day, millions could see it that wouldn’t otherwise ever see it in a museum.”

Advocates say the $15-an-hour contract is far from satisfactory for those working during one of the year’s biggest money-making televised sports events.

Featuring a who’s who of international artists, which also includes Jenny Holzer, Anish Kapoor, Teresita Fernández and even a delightfully weird vinyl mural by Texas artist Trenton Doyle Hancock, AT&T Stadium makes its art a centerpiece. The collection is prominently featured on the homepage of the stadium’s website; visitors can also take specialized art tours of the stadium.

I’m not getting my hopes up for a similarly enlightened experience at the new SoFi Stadium in Inglewood.

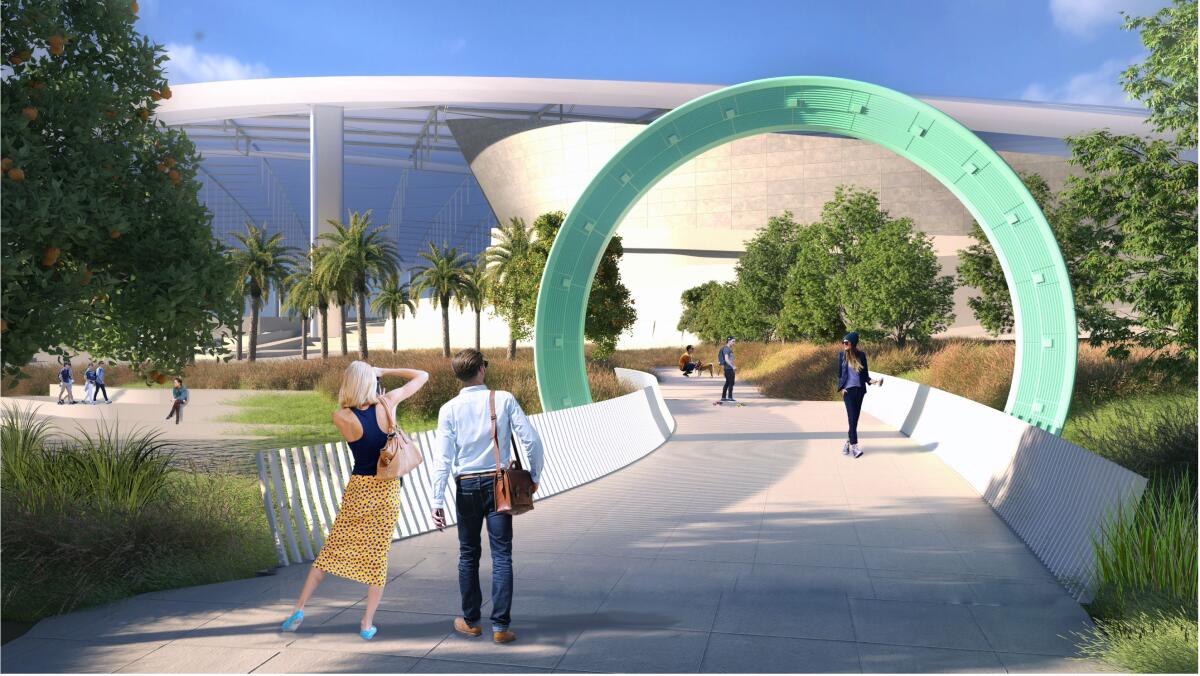

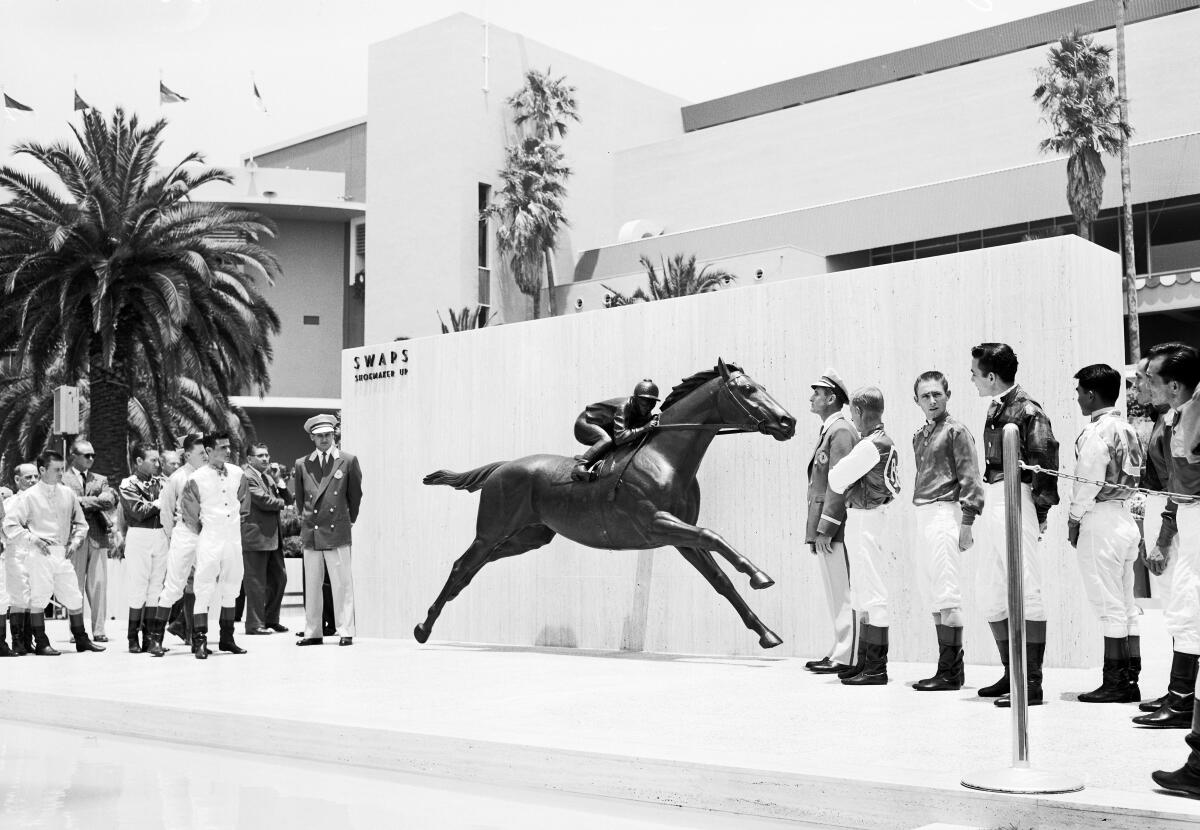

There are a lot of things SoFi gets right: the architecture — which is also by HKS — and a groundbreaking landscape design by the L.A.-based Studio-MLA. But the art program remains incomplete. Two major installations — by a pair of prominent Black artists, no less — appear to be stuck in limbo. Also nowhere to be seen: Albert Stewart’s historic sculpture of Swaps, the record-breaking thoroughbred that won the 1955 Kentucky Derby. The bronze, which shows legendary jockey Bill Shoemaker on the galloping steed, once occupied pride of place at the old Hollywood Park Racetrack.

The two missing commissions, as laid out in an art plan submitted to the city of Inglewood, included a pair of architectonic installations inspired by aqueous forms by Afro-Cuban artist Alexandre Arrechea, a founding member of the Cuban collective Los Carpinteros and a figure who has had major solo public art installations in New York City and at Coachella. (Arrechea’s massive yellow “Katrina Chairs” were an iconic part of the Coachella festival’s landscape in 2016.)

Also part of the art plan was a large-scale land-based piece by L.A.-born-and-raised Maren Hassinger, a profoundly respected sculptor whose works often explore the intersection of race and landscape. Her pieces, often made with gritty industrial materials such as galvanized wire, figure in the permanent collections of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. In 1979, she created a series of freeway-side sculptures titled “Twelve Trees,” which are now a permanent part of Cal State Fullerton’s sculpture collection.

A representative for Susan Inglett Gallery, which represents Hassinger, would not comment on the status of the artist’s installation at SoFi. Reached by telephone, Arrechea stated, “I don’t have recent news, but I’m looking forward to working on the project,” and declined to comment further.

Architecture firm HKS designed SoFi Stadium so that even the nosebleed seats deliver a terrific experience. The urbanism around it? Not so much.

Two art consultants for the project, Lesley Elwood and Tiffiny Lendrum, forwarded my queries to the publicity office for Hollywood Park, the mega-development where SoFi Stadium is located. Likewise, artist Christie Beniston, who designed the planned backdrop for Stewart’s “Swaps” — which was to be located at the stadium’s southeastern tip — said she did not know the status of her project and forwarded me to Hollywood Park. Everyone I reached out to for this story, which included other artists in addition to those listed here, signed nondisclosure agreements with Hollywood Park and therefore would not comment on the record.

In an email, a spokesperson for Hollywood Park says, “The project is ahead of the amount of funding that has been generated by the construction to date. Over time, we expect that additional development will fund a wide range of art to be programmed and performed at the site.”

To be certain, the stadium is not entirely bereft of art.

Already in place is a massive architectonic piece by Ned Kahn that covers the facade of a parking structure to the west of the stadium, as well as graphic works by Erik den Breejen and Katie Shapiro inside the stadium elevators, and a large-scale wall piece by Sandeep Mukherjee that inhabits the interiors of the adjacent YouTube Theater.

But with the Super Bowl upon us, in a stadium that sits at the heart of a city indelibly linked to Black culture in the 20th century, there are no completed works by a Black artist. I repeat: none.

And that isn’t because the art plan didn’t include works by Black artists, because it certainly did. It’s just that these are the last ones being executed by the developers (if at all).

A pair of sculptures by esteemed Los Angeles artist Alison Saar, whose work explores states of Black womanhood, is supposed to land on the southern edge of the complex’s Lake Park in June. (She was recently the subject of a critically well-received two-part survey at Pasadena’s Armory Center for the Arts and the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College.) And in process is a mural by painter Calida Rawles, who maintains a studio in Inglewood. Rawles, who is represented by Hollywood gallery Various Small Fires, is known for canvases that feature Black bodies floating in water in dreamy, buoyant states — one of which served as the cover art for Ta-Nehisi Coates’ novel “The Water Dancer.”

It’s unclear, however, whether Rawles’ mural will be complete in time for game day on Sunday. A press release about the mural program — which also includes pieces by feminist artist Eve Fowler and Canadian-born graphic artist Geoff McFetridge — gave only a vague promise of “February.” The spokesperson for Hollywood Park did not offer further clarification.

Before Stan Kroenke and SoFi Stadium, numerous groups tried to lure the NFL back to Los Angeles by proposing spiffy stadiums. Here’s how some looked.

In addition to those public art pieces, the stadium will host a show of works in late February from the Kinsey collection, a collection of Black art assembled by L.A. philanthropists Bernard and Shirley Kinsey, in one of its club areas. That, however, will be a temporary display.

Ultimately, the lack of a strong Black visual arts presence at the site during Super Bowl week is a serious misfire. Not only is it Black History Month, but this year the Super Bowl halftime lineup will nod to Southern California’s place in the pantheon of rap, with performances by Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, Mary J. Blige and Kendrick Lamar. The NFL appears to be attuned to the culture of the site; the developers at Hollywood Park, not so much.

Which also brings me back to the failure to install Stewart’s sculpture of Swaps. It would have been an opportunity to honor the site’s history.

I can’t lay this all on Hollywood Park. For one, we have been in a pandemic, which has delayed, well, everything. And there is the greater issue of the squishy nature of the development contract the city of Inglewood signed with the developers of Hollywood Park. The city gave the stadium a variance on the traditional percent for art ordinance, which requires developers to commission on-site art that comes to “1% of the construction project valuation.” In SoFi’s case, that’d come to a healthy $50 million investment in public art.

Instead, Hollywood Park has been allowed to spread an equivalent amount of spending over a 25-year period. In other words: Inglewood gave a wealthy developer a generation in which to make good on its art promises.

SoFi offers terraced gardens and vistas of the San Gabriels and Palos Verdes. Here are 5 places to soak up the best views and design twists.

In addition, the development contract pretty much writes Inglewood out of the process. As part of the variance, as stated in process documents filed with the city in early 2021, the city of Inglewood’s “Arts Commission does not have its traditional authority over the developers’ public art plans, public art works, art sites, art budgets, art content, art definition or developers’ expenditures.” Though the commission “has the responsibility to provide cultural witness on behalf of the city, as to the developers’ realization of their stated, mutable and ongoing goals.”

What “cultural witness” might consist of is unclear. Sabrina Barnes, Inglewood’s director of parks, recreation and library services, which oversees the city’s arts commission, did not respond to telephone and email queries from The Times.

The stadium’s art plan has — had? — promise. Here’s hoping it gets completed in my lifetime. In the meantime, for a good artistic experience at a stadium, I’ll be looking to Texas.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.