These walls do talk

BEFORE Bernard and Shirley Kinsey remodeled their cliff-side home in Pacific Palisades, they often climbed up on the roof of the original two-bedroom midcentury tract house to take in the magnificent view of Santa Monica Bay.

When guests visit, “people want to see the view. That’s what we do first,” Bernard Kinsey says.

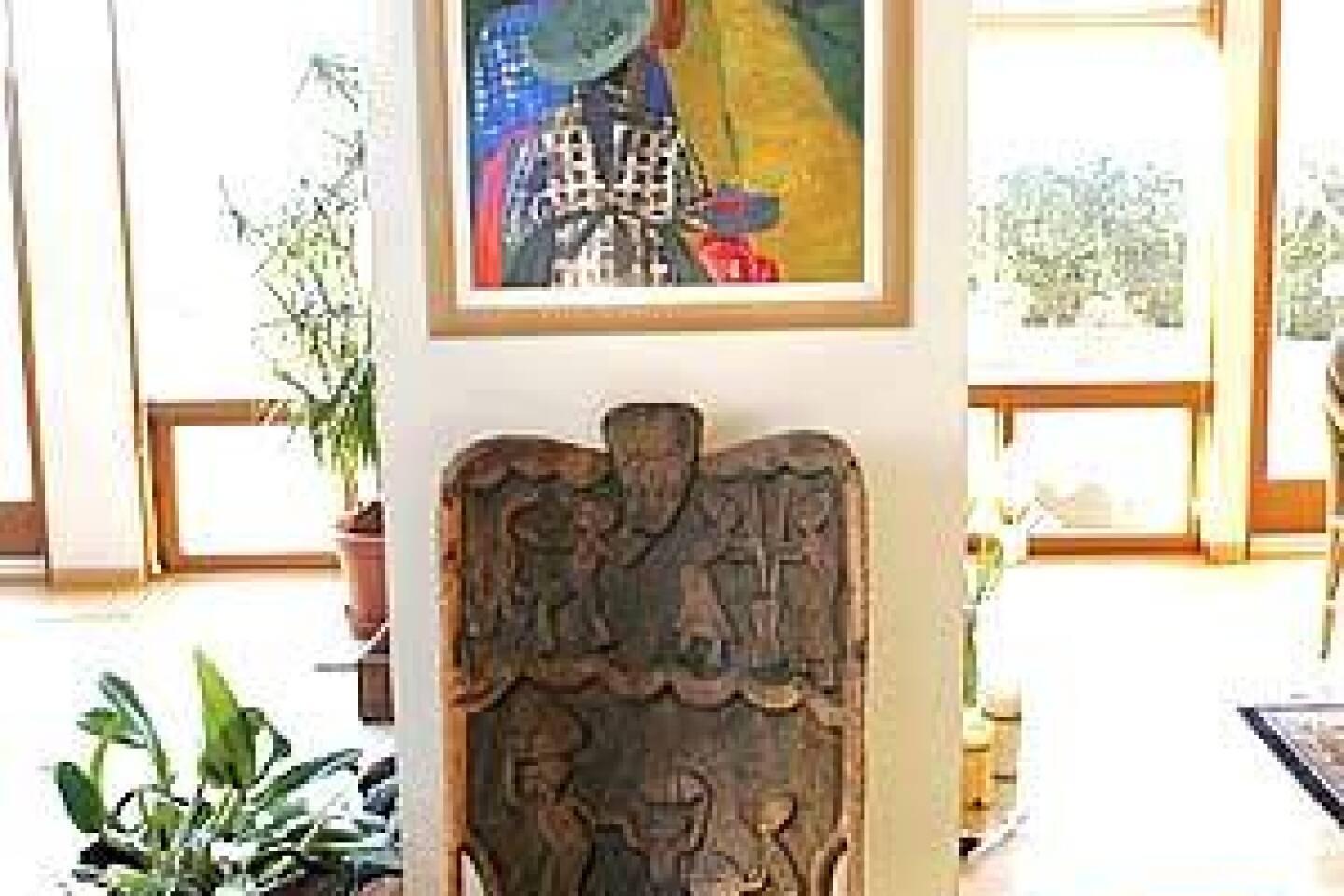

But the couple had more on their mind when they called architect Doug Breidenbach. The house also had to provide a suitable showcase for their extensive collection of African American paintings, sculptures, artifacts, antique papers and ephemera.

They depended on their friend Breidenbach, who had worked with them on four houses. “He knew our artwork,” Shirley Kinsey says.

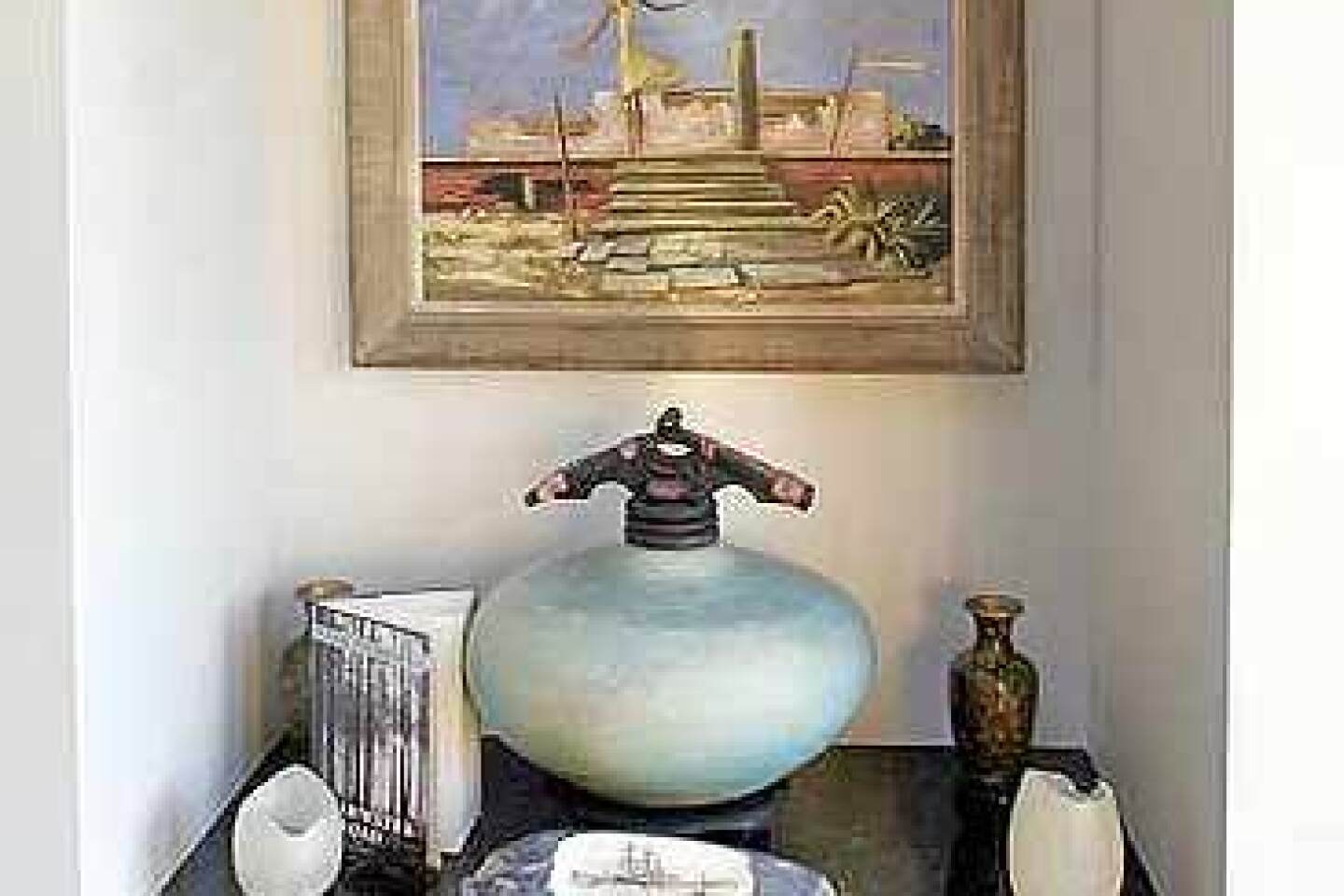

The result: a tri-level, five-bedroom Modernist house that refuses to play favorites between the views and the art. The home lovingly embraces the works with broad expanses of wall space, niches and alcoves while accommodating the ocean view with wrap-around decks.

Step through the glass-front entry past an Artis Lane portrait of the couple, a sculpture of a black female also by Lane, an Inuit soapstone polar bear and a turquoise abstract by painter Matthew Thomas.

Continue past two Ed Dwight sculptures of an elegant Masai woman and several pipers, a display of African masks and into the living room, which is dominated by four bold abstracts by Bill Dallas, and a large, lush violet landscape by Richard Mayhew.

There is so much more — a Tina Allen bust of Frederick Douglass; a painting of Southern black life by Jonathan Green; Aboriginal abstracts by Australian Colin Byrd — and this is just on the neutral ivory walls of the main floor.Though not exclusively black, the couple’s documents, artifacts, paintings and sculptures trace the introduction of Africans in the Americas through slavery and Reconstruction and on to their evolution as painters, from celebrated 19th century landscapes to contemporary abstracts.“The collection is just so much a part of the home. It’s everywhere in the home. I find that to be really special and significant. Its letters, broadsides, ephemera, sculptures, paintings,” says Steve Turner, collector and dealer of things African American, who owns a gallery in Beverly Hills. “You know collectors, but sometimes you don’t see the things. They’re put away. They live with things on a day-to-day basis. It’s always fun to go see what’s new.”

But the Kinseys’ latest acquisition, a bold yellow abstract diptych by Sam Gilliam, is currently hanging in a retrospective on the artist at the Corcoran Art Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Bernard, 62, likes to say that life has many chapters. The couple’s collection reflects their travels to more than 75 countries, family, memories, professional work, scholarship and a history well beyond the two of them.

“All of these pieces are part of telling a story of how the African American people became who they are. It is in the two-dimensional art, [and] the sculptures. It’s in the historical documents,” Bernard says. The Kinseys have one of the most important African American collections in the West, according to Atlanta art dealer, educator and attorney Jerry Thomas Jr.

For a photograph of black Sen. Hiram Rhodes Revels, who represented Mississippi during Reconstruction, Kinsey outbid the Smithsonian, which has an extensive collection of black art and also operates the Anacostia Museum and Center for African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

“The focus has a lot to do with legacy,” says Charmaine Jefferson, executive director of the California African American Museum in Exposition Park, which will exhibit some of the Kinseys’ art next year as part of a series on African American collectors.

From the Kinseys’ collection, she says, “You get the notion of African Americans as a broad people with a broad interest. [They] might have something that looks obviously black, and at the same time something abstract with no racial identity.”

“They might have a Ming vase or a polar bear from the North Pole,” she says. “It’s like loving Bach and Miles Davis and everything in between.”

“The collection is not only impressive,” says Atlanta art dealer Thomas, “it’s really a role model of what many collectors should be looking at. He [Bernard] doesn’t approach the art as mere decoration. He really understands the importance of art, and material culture — documents and books, and to approach it in a very thoughtful and mindful way. He knows where he’s going.”

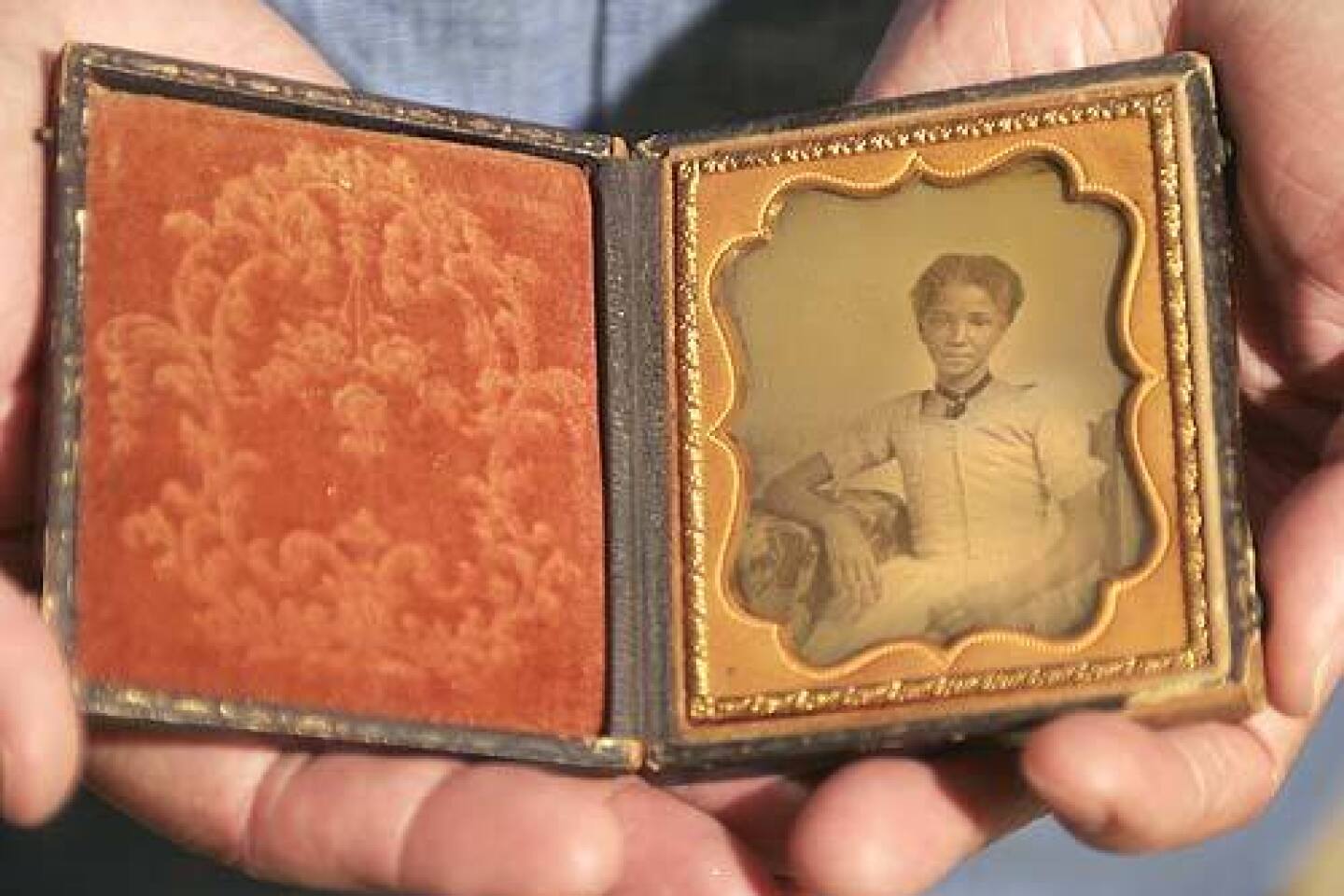

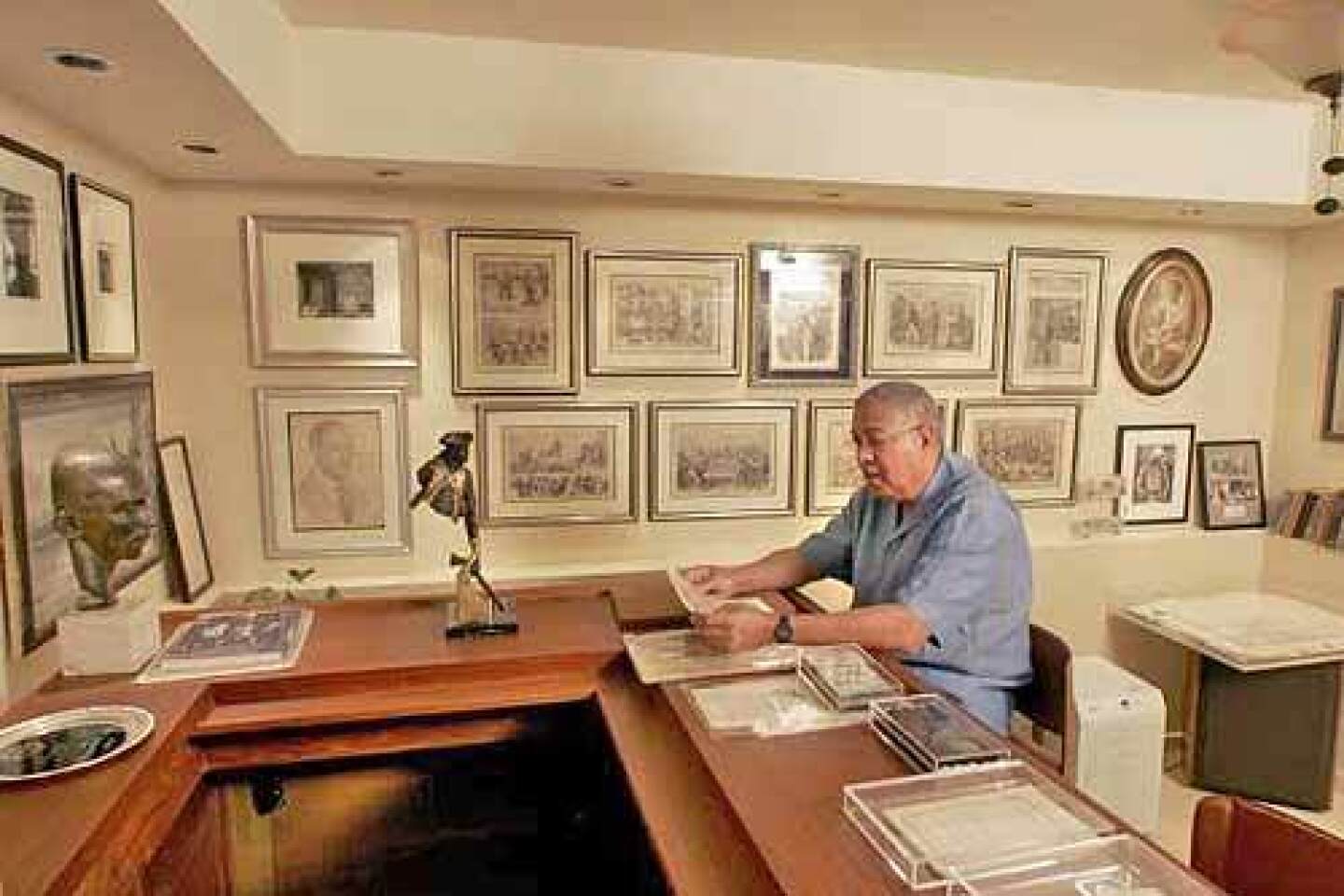

Follow Bernard downstairs along a narrow corridor into what was once the wine cellar and find what is now a humidified gallery that tells the story of African Americans. Visitors pass framed shackles intended for a female slave, circa 1853. An 1899 sculpture of a slave boy by May Howard Jackson stands sentinel.

He reaches for his earliest pieces: treaties from 1713 that gave the British the rights to take slaves from West Africa. He picks up a first-edition copy of the letters of an ex-slave and opera singer Ignatius Sancho published in England in 1782. He also owns a first edition of the first book published by a former slave in the U.S., poet Phillis Wheatley in 1773. He runs his fingers across shipping log books that enumerate 3.8 million Africans taken by the British from 1795 to 1806.

He reads from letters: A master doesn’t have the heart to tell his 17-year-old chambermaid Frances Crawford that he is selling her away from her entire family to pay for horses and a new stable; a benevolent white owner, Mrs. Graham, sells five slaves — a wife and four children — to the free black husband for $100 to reunite them; a Union soldier witnesses a slave massacre on a Southern plantation to prevent black men from joining Northern troops.

Kinsey moves on to a speech by the abolitionist Douglass. The woodcuts, lithographs, tintypes, daguerreotypes and photos chart black images and bridge the centuries.

His landscapes, portraits and still lifes introduce 19th century black masters: painters Robert S. Duncanson, Henry O. Tanner, Edward Bannister, Charles Ethan Porter and Grafton Tyler Brown. In a hall lined with canvases, Kinsey points out the earliest works and says, “These are the first examples of African American artists painting about and of themselves.”

He continues along the corridor, calling the roll of great African American painters of the 20th century: Jacob Lawrence, Palmer Hayden, Elizabeth Catlett, Lois Mailou Jones and Margaret Burroughs.

Kinsey has them all, and many more.

While he is busy connecting historical dots, Shirley, 59, is upstairs in the dining room. She is pointing out a Huey Lee Smith painting done in 1951. “That’s me jumping rope,” she says, gazing at the girl in the vivid painting. It’s not really.

The house has an open floor plan, and sunlight bathes every room. “I design houses that typically have a lot of light and a lot of wall space for art,” architect Breidenbach says.

But they couldn’t do the typical Westside tear-down. “There were some geological issues. If we tore the house down, we would lose some vested rights,” he says, “We had to design around the original foundation. We couldn’t just scrap it.”

So they built up, carefully facing most rooms, including the kitchen and bedrooms, toward the ocean. Because of the intense sunlight, the oversized windows are shaded like the one behind Shirley in the dining room.

“I like things that remind me of my growing up days.” Like the painting of a house on stilts by Claude Clarke that reminds her of her great-grandmother’s home in the Florida countryside.

“Some pieces take me back to a place I’ve been,” Shirley says. Like the Australian outback where she purchased abstracts. She says, “All those little dots and all those little figures represent some aspect of their ancestry.”

Like the collection, eclectic but with a purpose, Bernard cannot be easily pegged. He is best known in Southern California as a former co-chair of Rebuild Los Angeles, which then-mayor Tom Bradley set up after the 1992 civil unrest to develop the riot zones.

Before RLA, Kinsey spent 20 years at Xerox, where he became No. 1 in national and regional sales. When he was promoted to vice president, the black Xerox employees gave him a portrait of his son Khalil by Artis Lane; it is his wife’s favorite piece. When he retired, the same group gave him a carved African chieftain’s chair.

During his time at Xerox and since then, he and Shirley, his wife of nearly 39 years, have built, remodeled or redecorated 13 houses, half in Pacific Palisades. He says his passion for homes began with the elegant Bahamian-style house his father built six decades ago, in the black community of West Palm Beach, Fla. But Bernard doesn’t want to be labeled a real estate developer, philanthropist, consultant or art collector. He refuses to be categorized.

Shirley was a teacher in Compton and worked at Xerox in training, sales and management.

Well-connected members of the Southern California African American elite, the Kinseys entertain often, and frequently hold fundraisers at their home for their favorite causes such as sending children to college; their alma mater is historically black Florida A & M University in Tallahassee.

In conversations, Bernard often takes the lead, ready to give an art or history lesson, but his wife is no pushover. She has veto power over his art purchases just as he has over her choices.

“One ‘no’ stops it,” he says. Both say the noes are rare whether they are in an art gallery contemplating a purchase or sitting on their deck savoring the view.

*

Gayle Pollard-Terry can be reached at [email protected].

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.