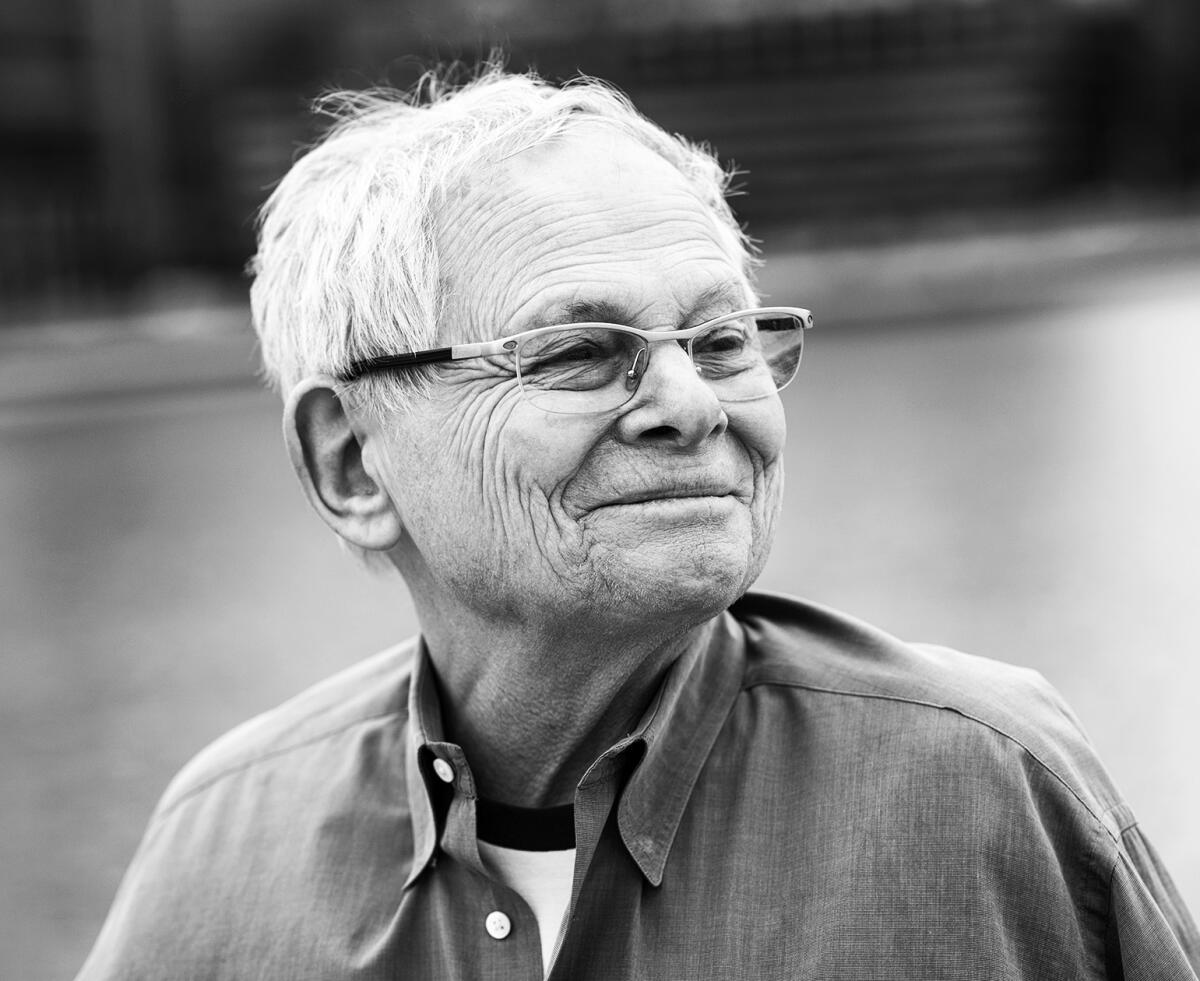

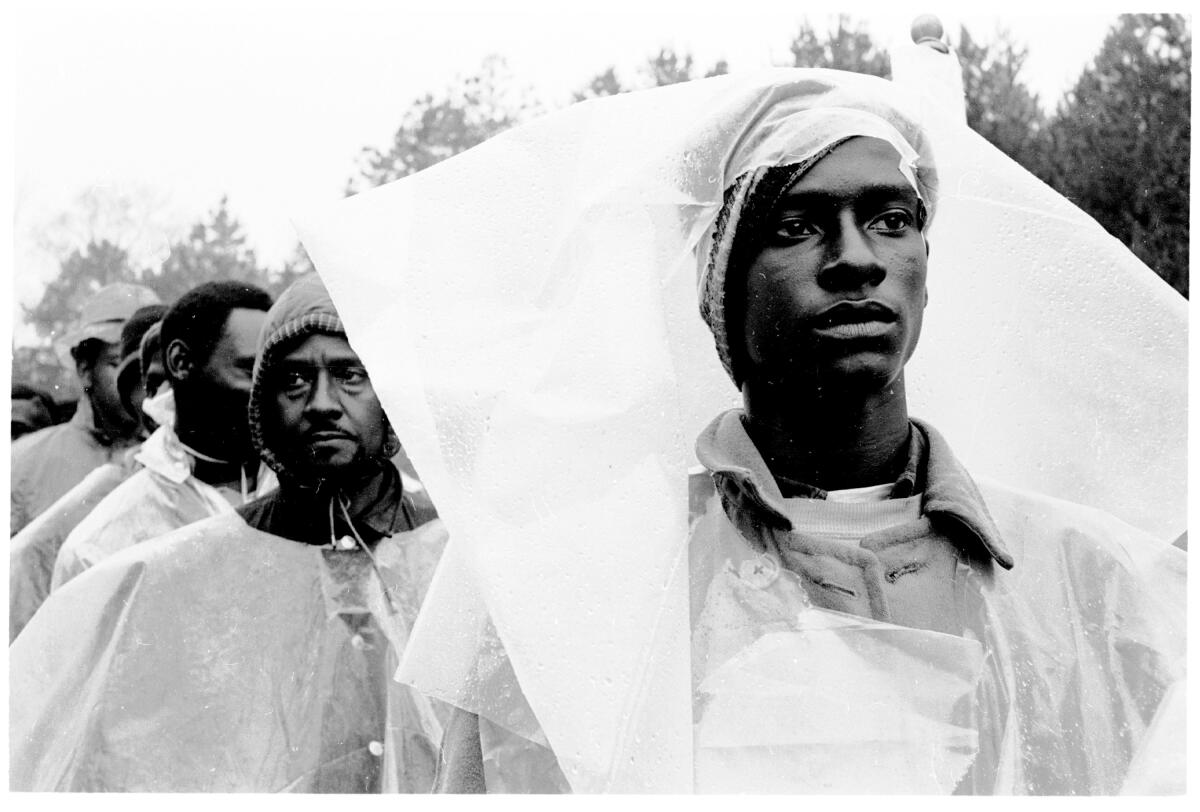

Photojournalist Steve Schapiro, who died last week, left images that reach into the soul of history

In the hours after the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tenn., in 1968, Steve Schapiro walked into a room — not the one at the Lorraine Motel where King had been staying, but in the rooming house across the street, from which James Earl Ray fired the fatal bullet.

While photographers descended on the Lorraine Motel in hopes of depicting the civil rights leader’s final moments, Schapiro had a different idea: to capture the barren bathtub where Ray took his life and the handprint he left on the wall.

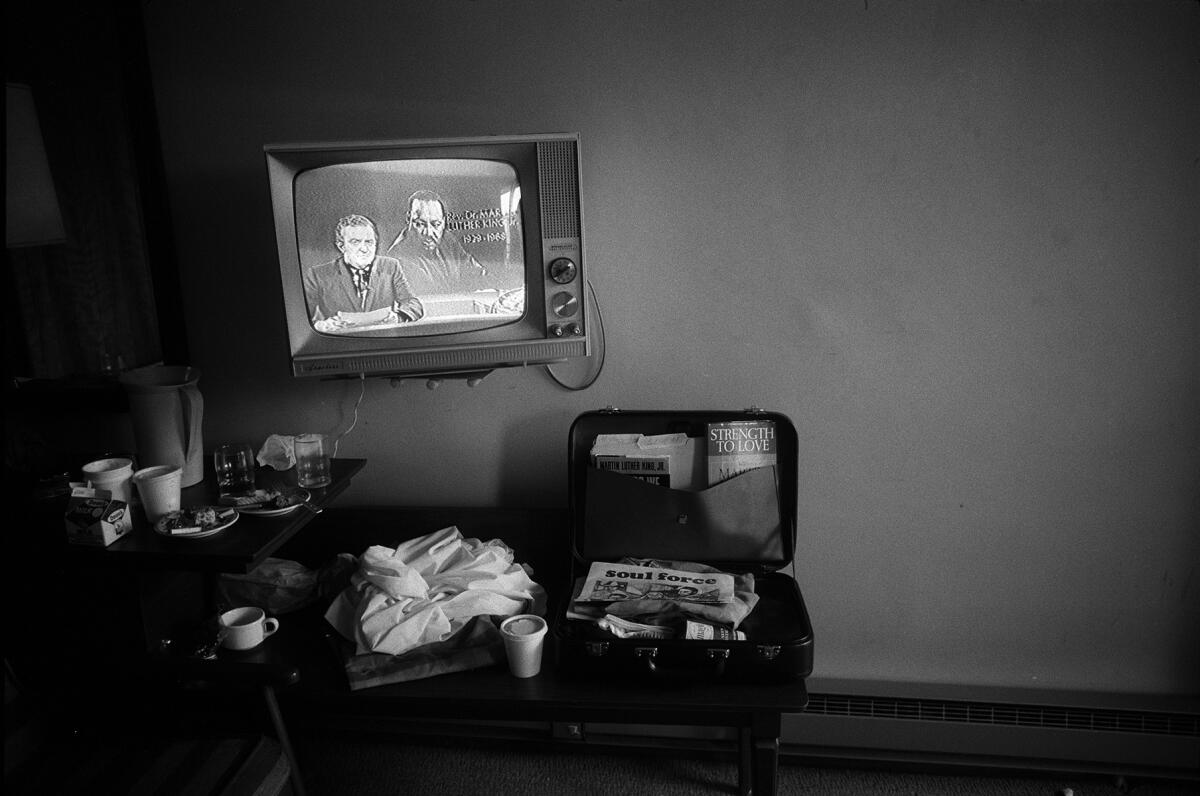

Schapiro walked into King’s room soon after and photographed the void: an empty milk carton, an open suitcase containing King’s sermon book “Strength to Love,” and the empty air that occupied the space where the man should still have been standing.

“The only presence [King] had was on the TV screen, and from that moment forward, his only presence was going to be in the air and transmitted through pictures,” said David Fahey, a longtime friend of Schapiro and director of the Fahey Klein Gallery in Los Angeles. “He did this scene that the other photographers didn’t see. That takes a very sharp instinct. He just knew what elements he had to include to make his pictures noticeable.”

Fifty-four years later, Schapiro died of pancreatic cancer in Chicago on Jan. 15, the same date as King’s birthday. He was 87.

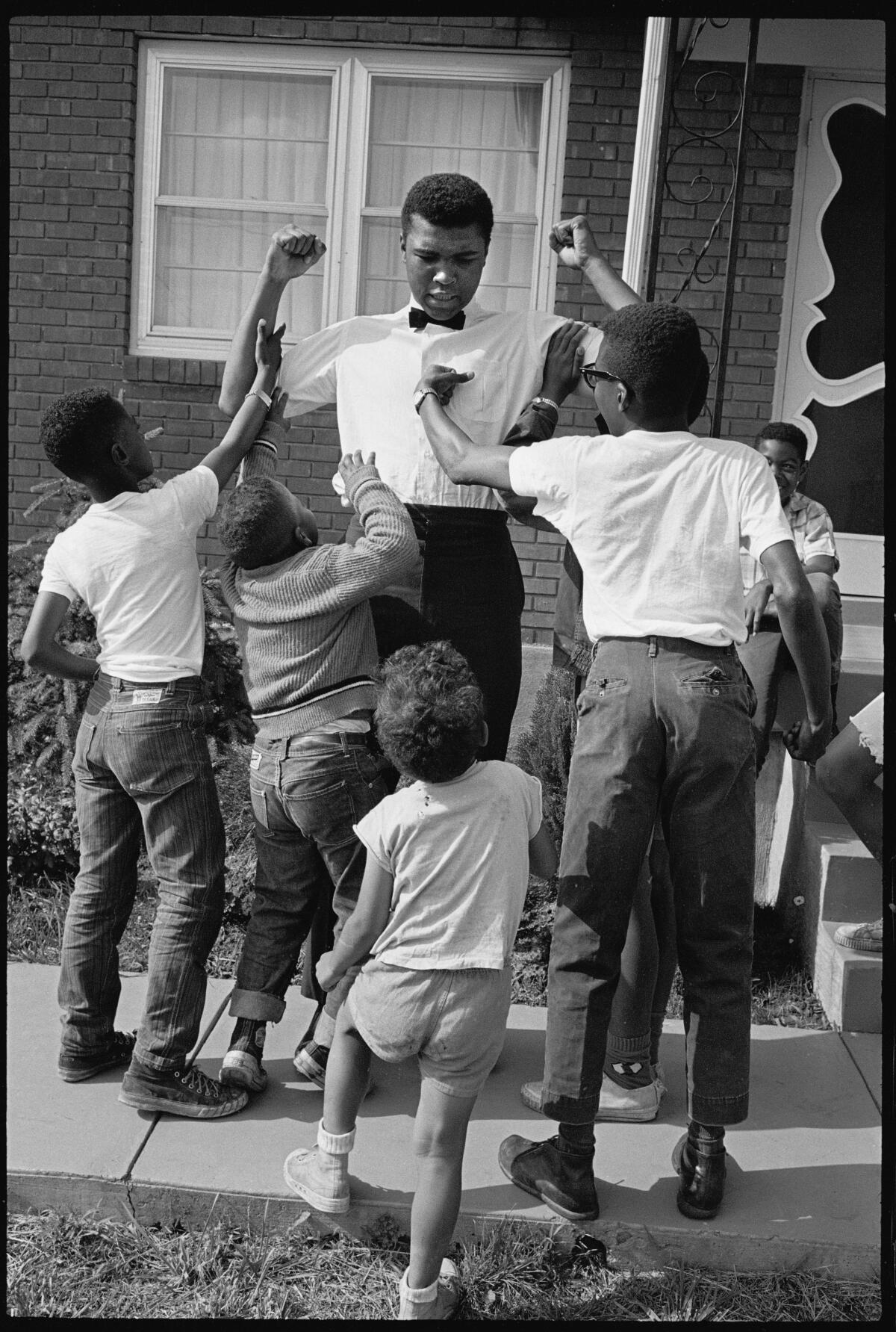

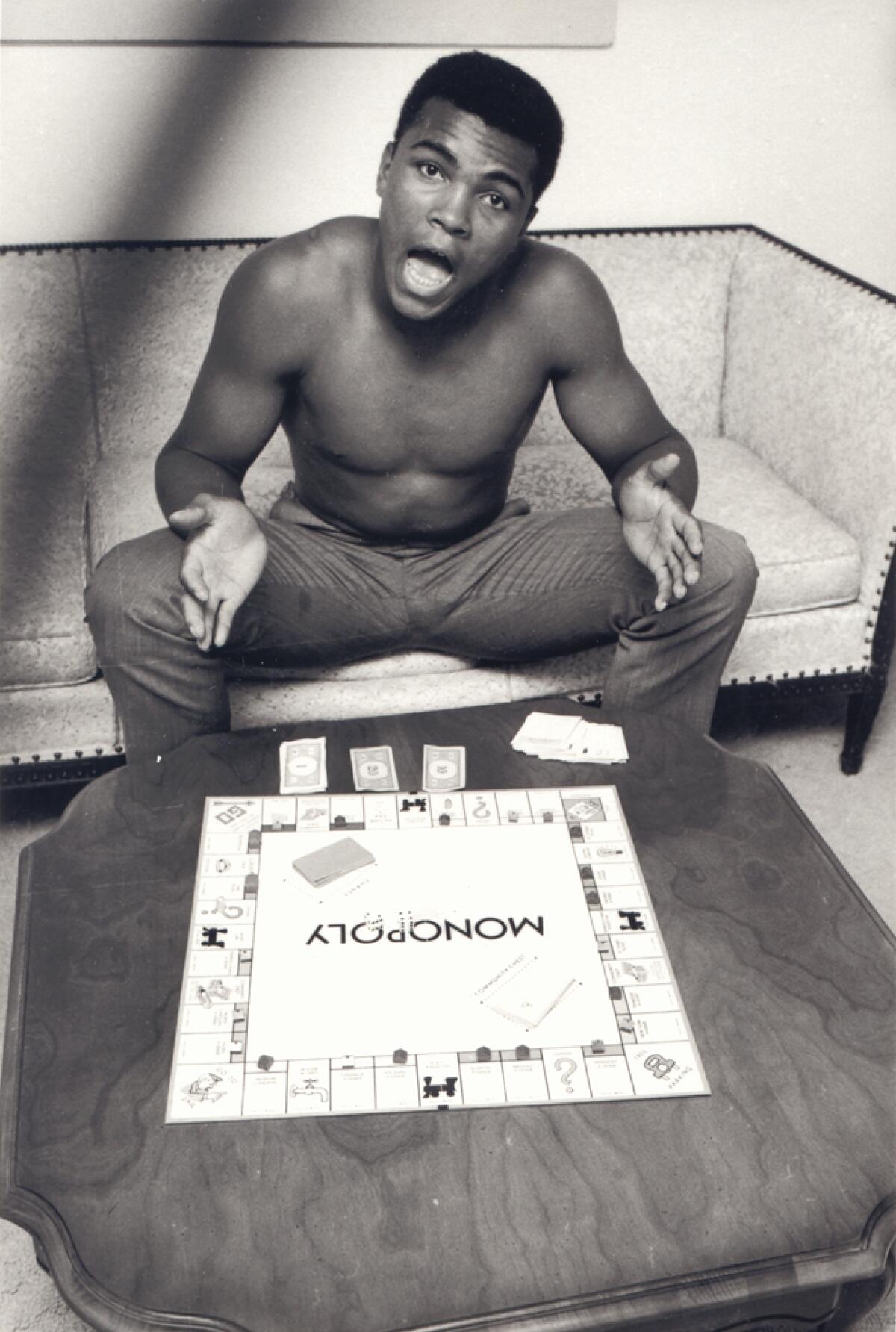

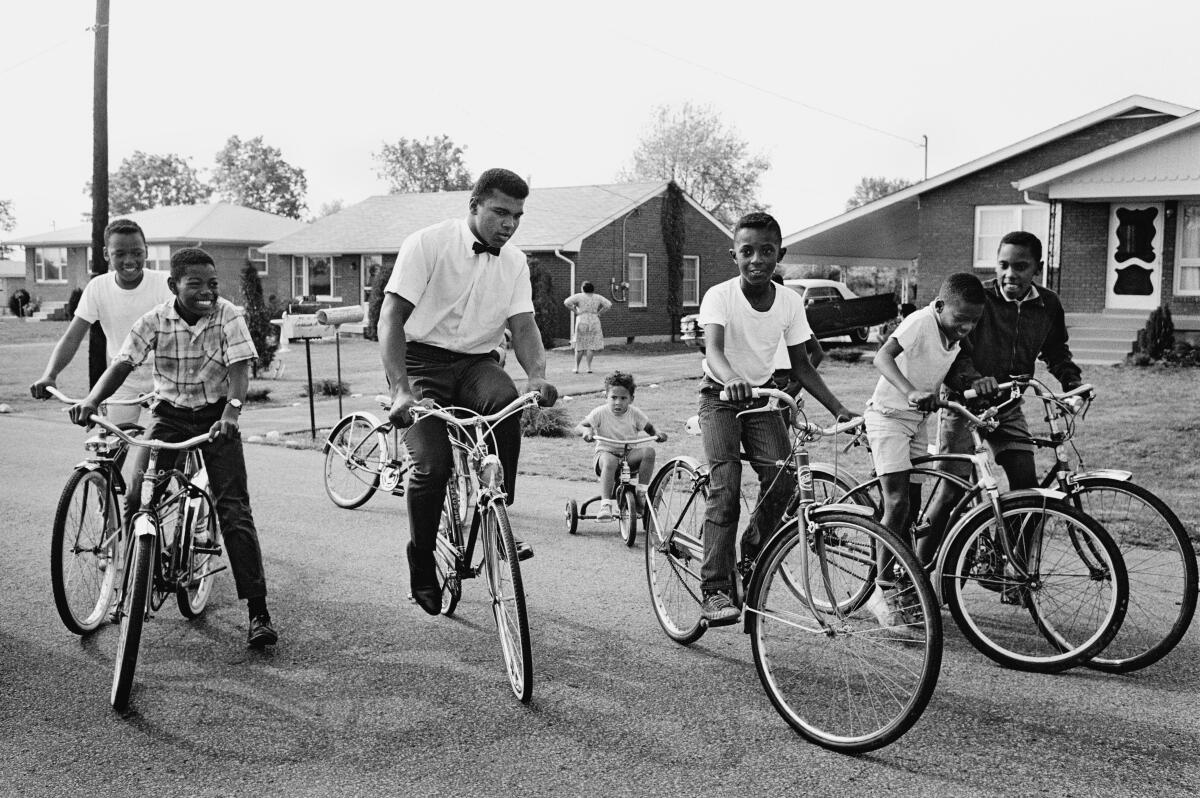

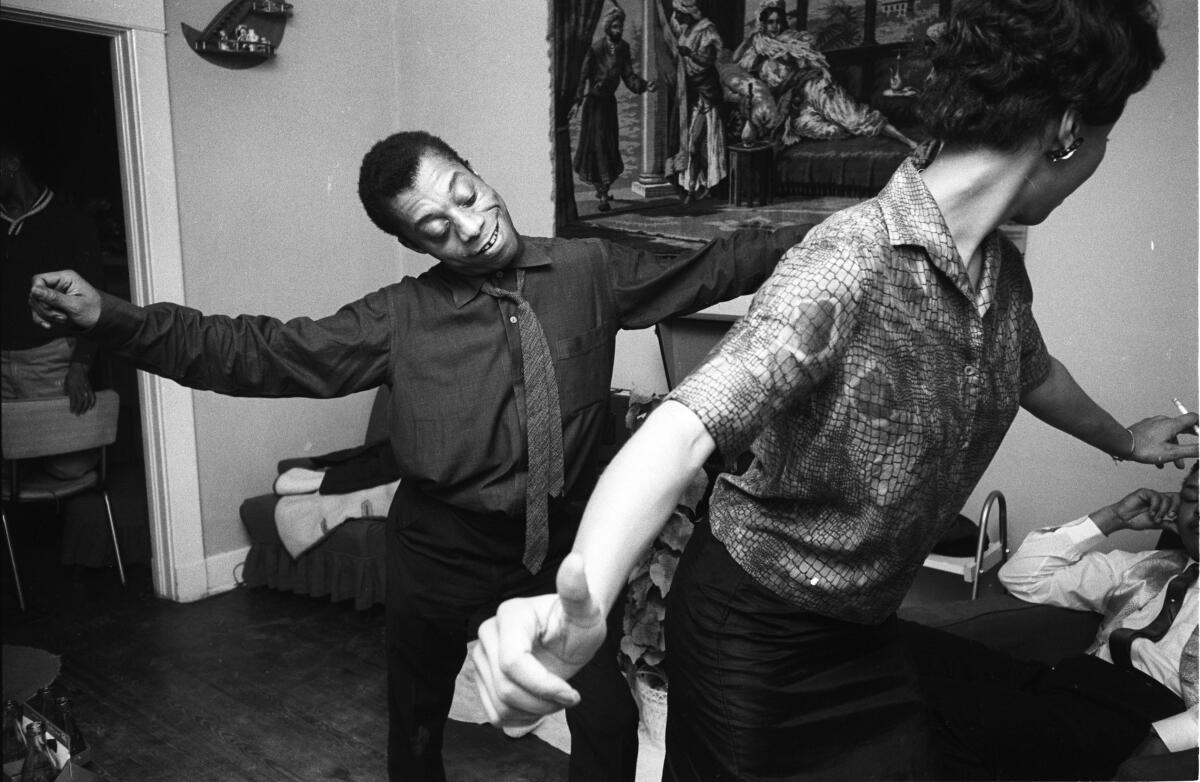

Across his career, the photographer documented “poodles and presidents,” addicts, farmworkers and Muhammad Ali, and everything in between. In Fahey’s eyes, there are six skills required to create unique, indelible pictures: instinct, intuition, curiosity, experience, trust and talent.

Schapiro had them all.

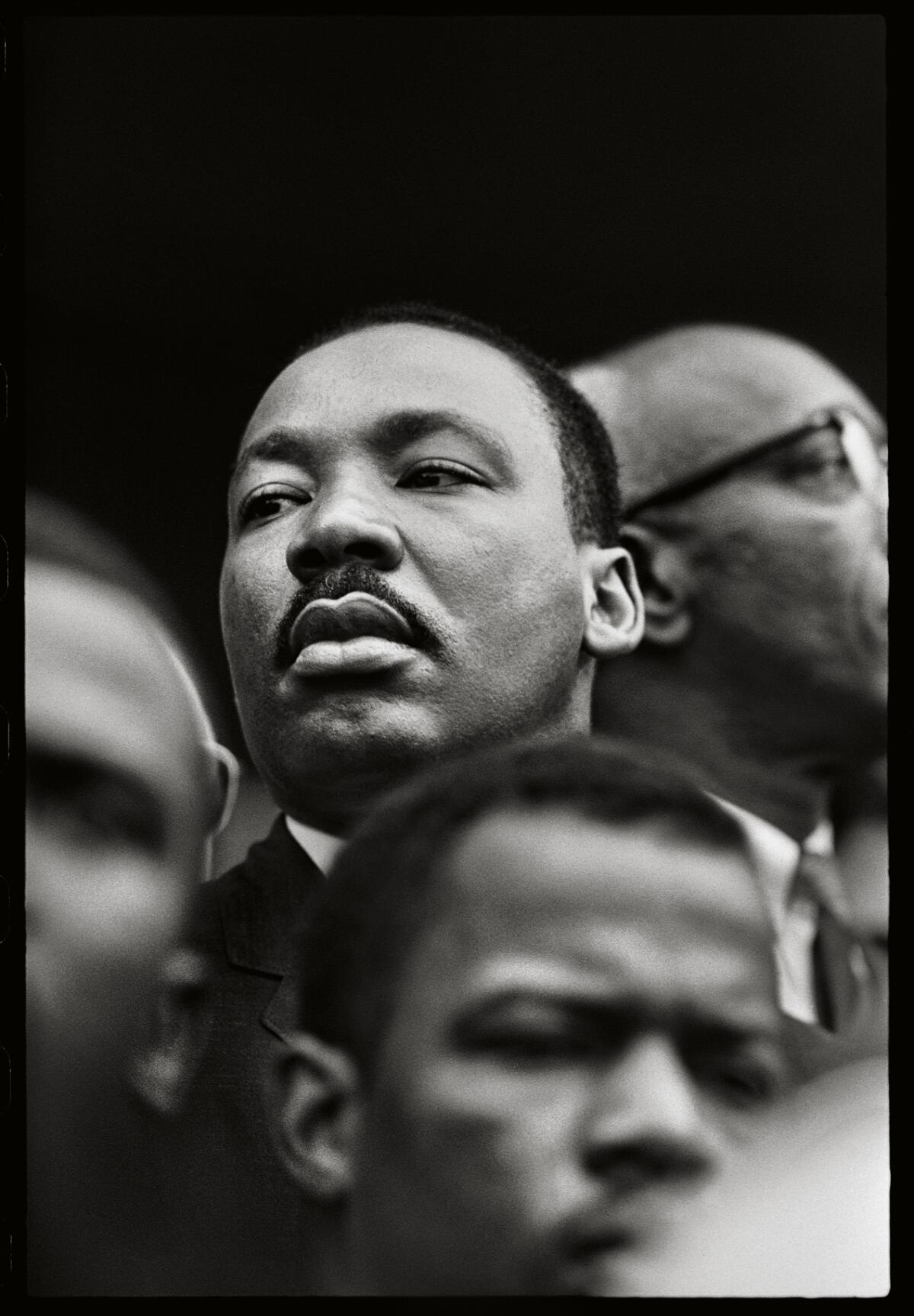

“He made the kind of images that reminded you to contemplate,” Fahey said. “Either historical moments or influential people. He just knew how to reach into their soul and make that photo that projected their personality in the best possible way.”

Born in New York City in 1934, Schapiro first picked up a camera at a summer camp when he was 9. Instantly enamored, he spent his youth roaming the city, turning the sights around him into images that would soon spark a career.

“I try to be a fly on the wall as much as possible,” Schapiro told the Los Angeles Times in 2013. “For me, emotion is the strongest quality in a picture.”

Steve Schapiro’s photos in ‘Then and Now’ offer a mix of emotions

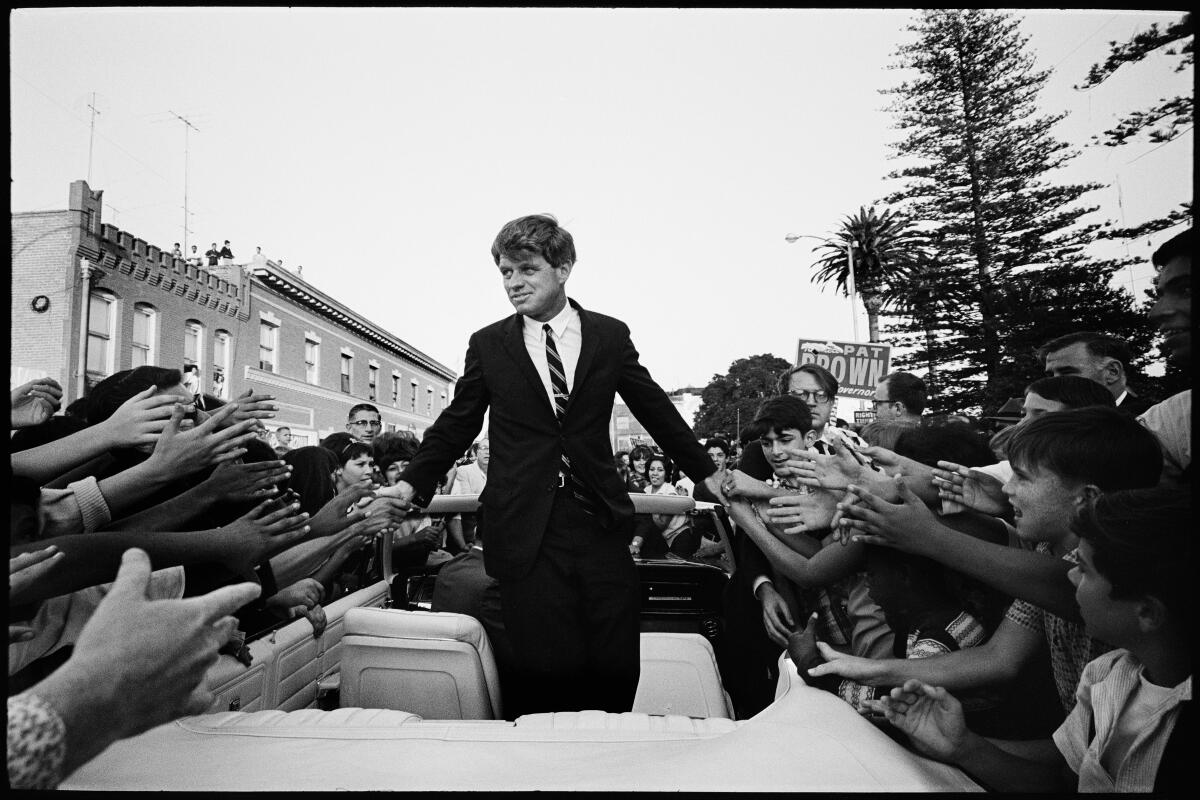

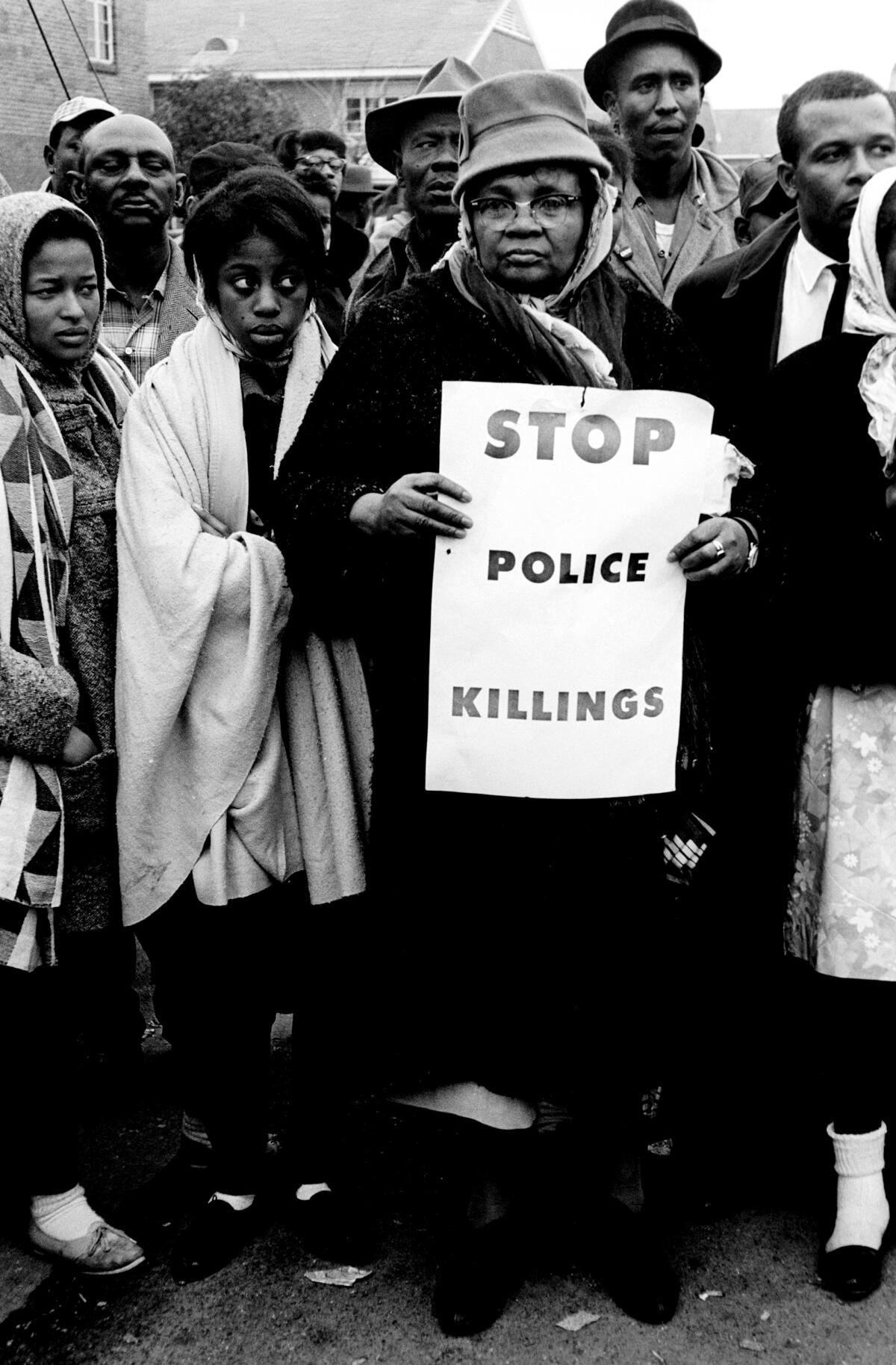

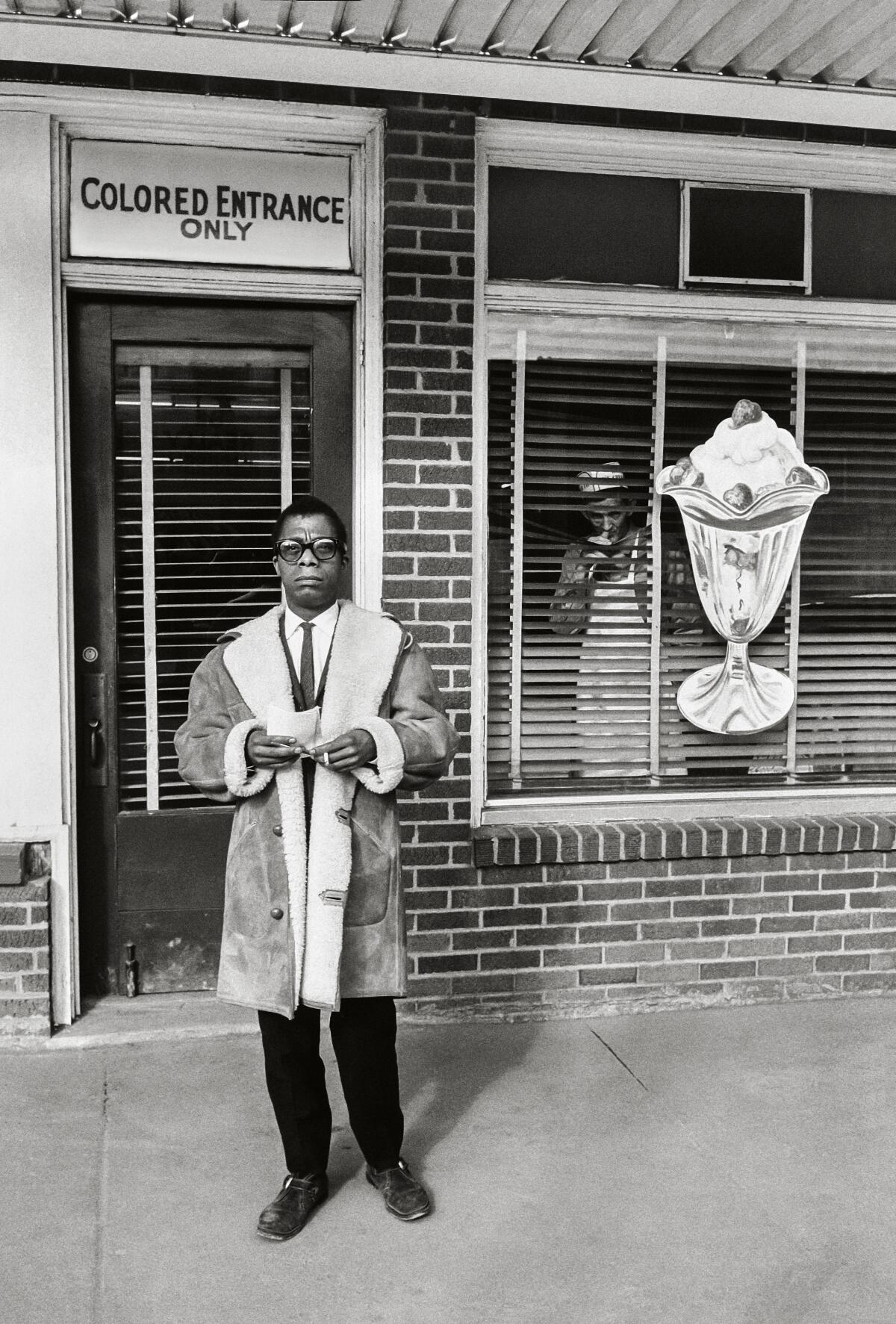

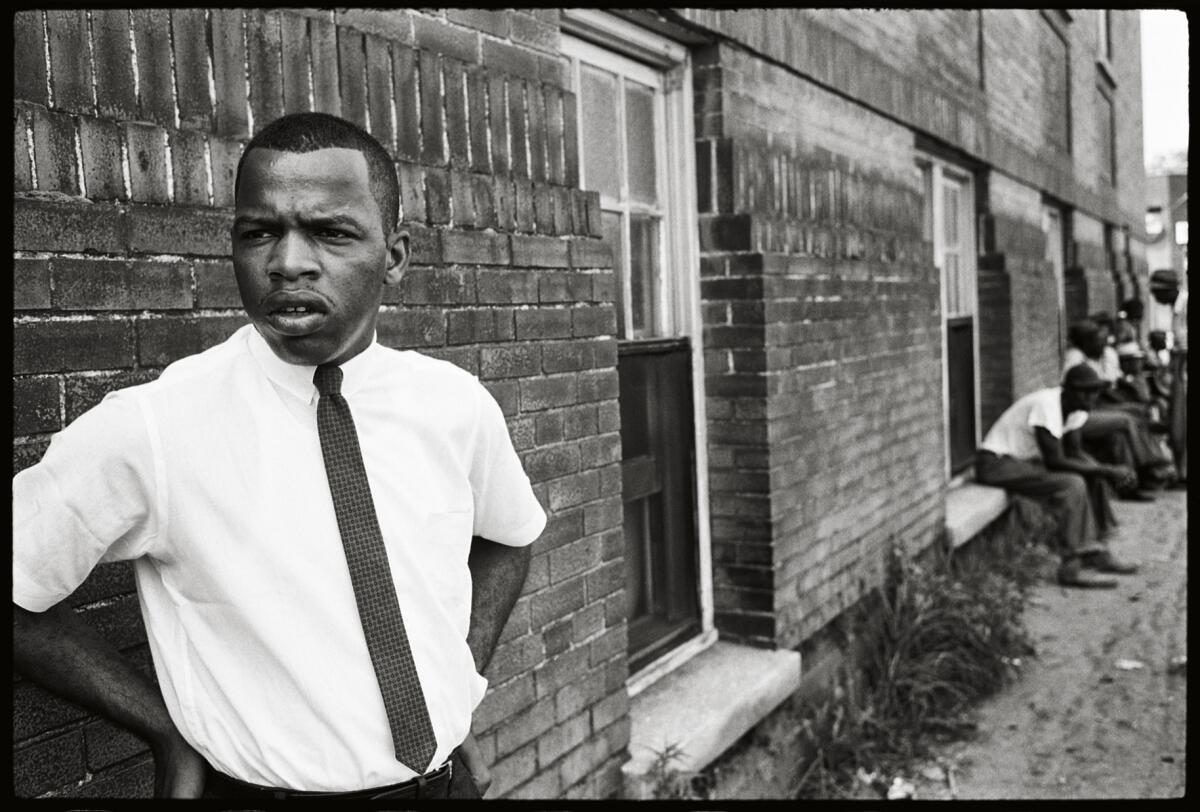

He began working as a freelance photojournalist in 1961, the start of a decade he called the “golden age in photojournalism.” He captured some of the defining moments during a critical turning point of American history, including Robert F. Kennedy’s presidential run, the “Summer of Love” in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood and the civil rights movement.

“Photojournalist Steve Schapiro has passed away,” filmmaker Ava DuVernay wrote on Twitter. “He was important to the movement. He photographed the March on Washington and Selma to Montgomery march. His images moved minds during a crucial time. This is my favorite photo by him of Dr. King. May they both rest in peace now.”

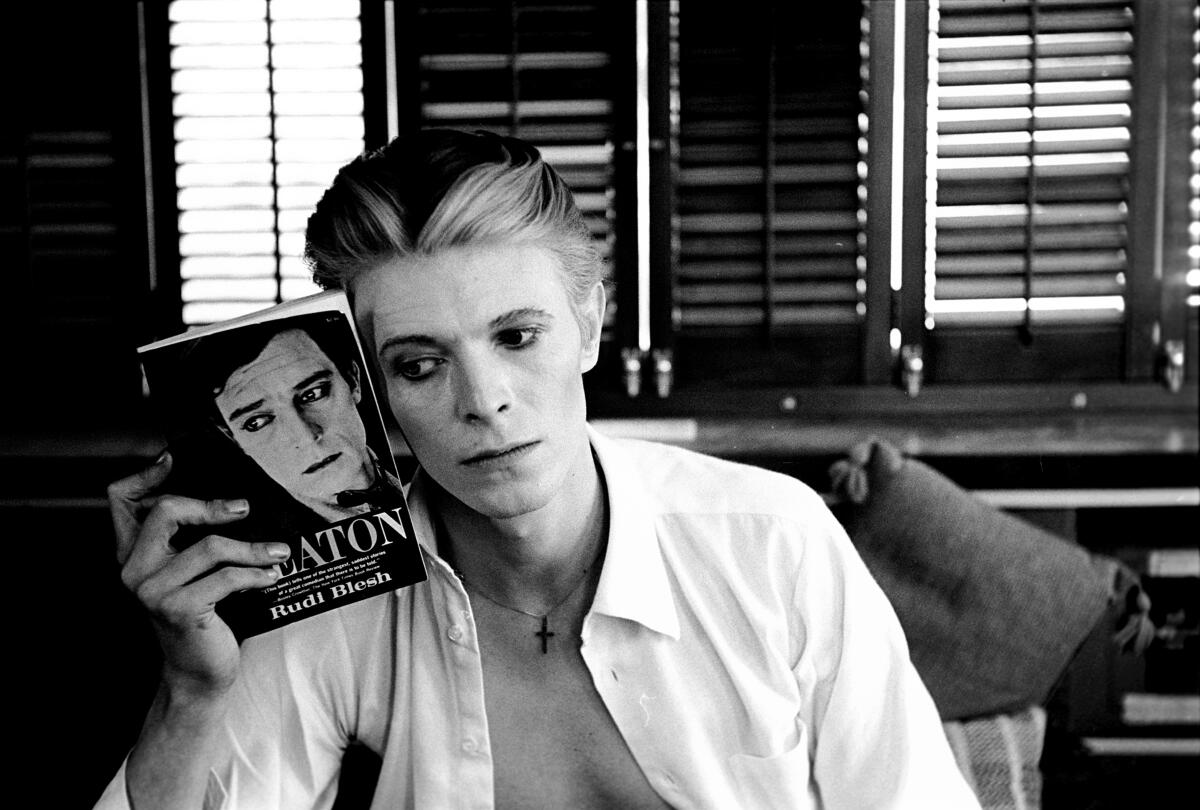

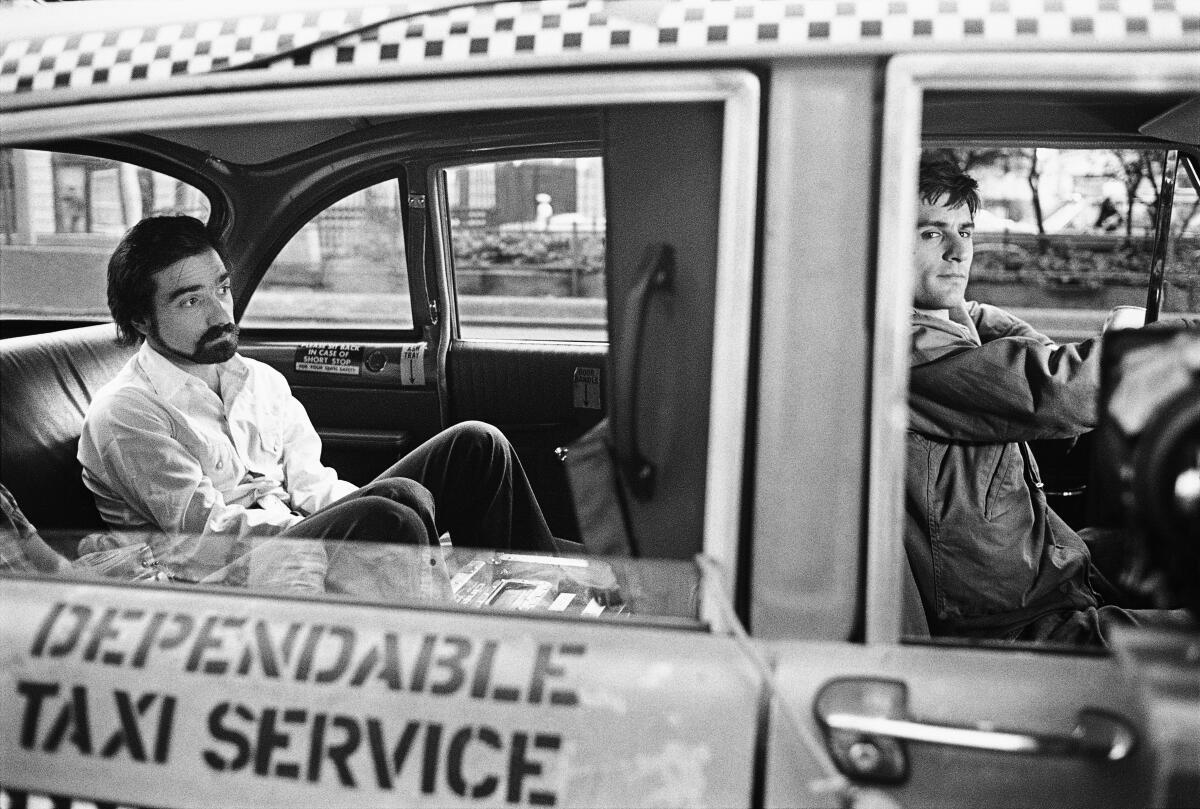

In the following decade, Schapiro turned to the entertainment industry as the photo magazines he’d freelanced for, such as Look, began to close. He created images for powerhouse films such as “The Godfather,” along with profiles of icons such as David Bowie and Oscar-winning actor Gary Oldman.

Oldman met the photography master during a shoot on the backlot of “Bram Stoker’s Dracula.” During a break in the production, Oldman lighted a cigarette, and Schapiro seized the candid moment — capturing him mid-smoke in full costume as the Transylvanian vampire. The spooky, smoky image remains one of Oldman’s favorites.

“He already comes with a reputation, so you know that he’s ... very good at his job,” Oldman said. “He’s a great photographer. But above and beyond that, he was just always very lovely to be around. Great energy. Loved life. Loved just being out there and being creative in the world.”

Oldman knew Schapiro primarily through his wife — photographer and art curator Gisele Schmidt.

His kind and inviting aura, Schmidt said, set Schapiro apart from his contemporaries and allowed him to conquer any photographic genre with ease. To Oldman, Schapiro was “an angel of a man.”

Oldman says the couple have about 10 Schapiro photos in their collection — including a doorframe-size print of filmmaker Bob Fosse and actor Dustin Hoffman leaping through the air.

“He was able to do it all,” Schmidt said. “And it is a testament not only to the greatness of him as a photographer ... but also just because of who he was. Because he made everybody feel comfortable. And that is such an extraordinary trait to have, is to be able to befriend anyone — to be able to go in and shoot any subject.”

Schapiro was a seeker, with an everlasting curiosity that drove him to explore new realms at every turn. Through it all, Fahey said, he remained deeply spiritual, embracing core tenets of Buddhism, Christianity and Judaism without assigning himself to a singular religion.

Those who knew Schapiro best were taken by his humility; still, he liked to refer to his career as “legendary,” a description made even more concrete as he saw his visceral images on the walls of homes across the nation.

“He began seeing how many people loved his work and were willing to purchase the work,” Fahey said. “It’s not like a pretty flower or a beautiful sunset. It was hard-hitting, message-driven photographs. They had their own innate beauty, but it’s not typical beauty.”

To the end, Schapiro transcribed the world around him through his camera, even after he was diagnosed with Stage IV pancreatic cancer in June 2021. While he was sick and isolating in his Chicago home during the COVID-19 pandemic, Schapiro snapped a series of photos from his apartment window of people swimming in Lake Michigan down below.

One of the final images Schmidt and Oldman received from Schapiro’s wife was of the photographer ill in his bed, holding a camera in his hand.

“Even being sick and at home and in his bed, he still had the camera, clicking away,” Schmidt said. “No matter where he was, what he was doing, who he was talking to — that camera was always going.”

In lieu of flowers, his wife, Maura Smith, requests that donations be sent to St. Sabina Church in Chicago.

Below is a sampling of Schapiro’s photography.

Times staff writer Christi Carras contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.