By scanning her own hands, Barbara T. Smith presents an ode to the aging female body

We think it is our minds that make us human, but it’s really our hands.

Hands, with their conveniently placed opposable thumbs, allowed humanity’s biological ancestors to better grasp surfaces, manipulate objects and wield tools.

Hands figure prominently in humanity’s earliest artworks: cave paintings, scattered all over the globe, including one of the earliest in Indonesia, believed to be almost 50,000 years old. In the Peruvian Andes, a temple structure at Kotosh, a preceramic archaeological site that dates from 2000 to 1800 BC, features a frieze of two delicately crossed hands.

Hands appear in countless artist studies (Leonardo da Vinci produced some extraordinary ones) and in iconic finished works, such as the powerful, oversized right hand on Michelangelo’s sculpture of “David,” ready to strike down Goliath.

Hands, in their various poses, can be used to symbolize power, rejection, friendship and love. Even in our postindustrial age, there remains something charged about a work that bears the mark of the artist’s hand.

It is the artist’s hands that figure in “Signifier 2,” 2016, by Barbara T. Smith, which is currently on view as part of a group show at the Cirrus Gallery in downtown Los Angeles. “Holy Squash: Jibz Cameron, Jackie Rines, Barbara T. Smith” was organized by critic and independent curator William J. Simmons and juxtaposes work by three L.A.-based, feminist artists who engage the body in ways vulnerable, humorous and delirious. The show’s name is inspired by a 1971 performance by Smith titled “Celebration of the Holy Squash,” which created a religious relic out of leftover foodstuff.

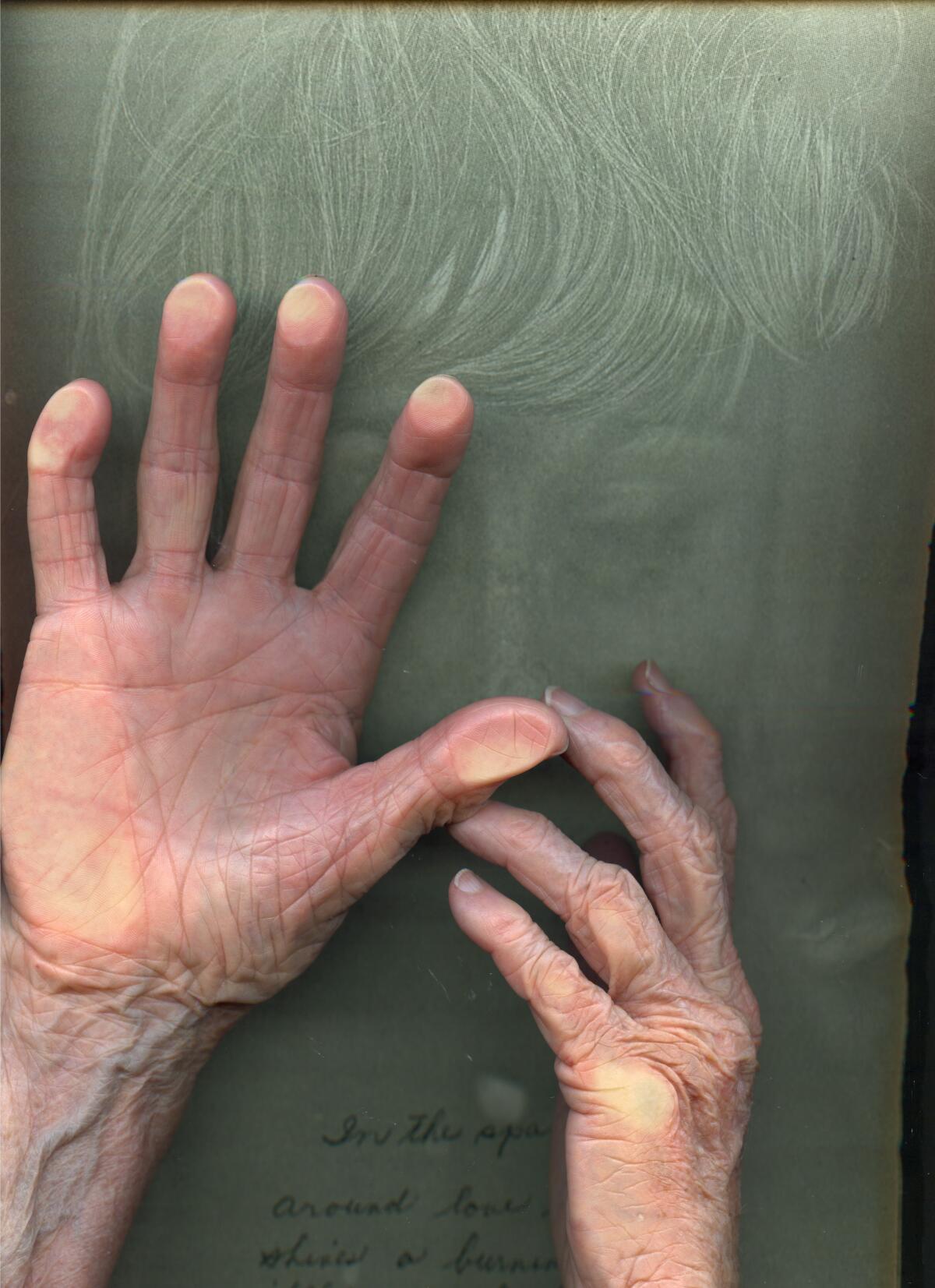

“Signifier 2” is part of a series of works in which Smith scans fragments of her own body on a flatbed scanner, then presents the resulting images as large-scale inkjet prints. These are ghostly, yet elegant — capturing the spots and papery texture of her aging skin, fingers torqued by arthritis, knuckles rendered white by the pressure of the scanner glass. Surrounding her fingers is a murky ocean of black.

The underrated Smith was a key player in the Southern California arts scene of the late 1960s and ’70s. She and a group of fellow graduate students from UC Irvine, including Chris Burden and Nancy Buchanan, established the experimental F-Space Gallery in Santa Ana, where Burden staged his infamous work of performance, “Shoot.” Smith also staged works there, such as “Ritual Meal,” from 1969, in which guests donned surgical scrubs and ate a bizarrely elaborate meal — a plate of cottage cheese with a single chile, chicken hearts boiled in red wine — as footage of the cosmos and a beating heart were projected in the space.

F-Space was the site where she produced a small, prototype version of her installation “Field Piece,” which was later shown in whole for the first time at Cirrus Gallery in 1971. That work, fabricated with a crew of designers and engineers, consisted of more than 180 translucent resin shafts, each nearly 10 feet tall, through which viewers would wander like ants in sci-fi grass. The “blades” were designed to turn various shades of orange, pink, yellow and violet as the participants triggered the delicate wiring underfoot. At the opening event, those participants were naked.

A surviving fragment of the installation went on view as part “State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970” at the Orange County Museum of Art in 2011 (part of the first wave of Getty Foundation-funded Pacific Standard Time exhibitions held in Southern California).

PST: Barbara T. Smith’s life in the avant-garde shadows

The artist has deployed technology in other curious ways too. In the mid-1960s, she rented a Xerox machine and began making images of her body juxtaposed with various objects. It was a series that arose out of rejection.

“I had this idea for a great lithograph, so I went to this lithography workshop called Gemini and said, I’d like to make a lithograph at your place and they sort of smiled indulgently, ‘Well, we don’t usually have someone work here unless they have a gallery,’” she told the culture journal the White Review in 2017. “I realized what was going on and I was just furious. I thought, well, lithography isn’t a print medium of our time, it’s from the nineteenth century, it’s already passé. So what’s the print-making medium of our time and I thought, it’s business machines.”

The newer works, created on a flatbed scanner in Cirrus’ workshop (the gallery is also a print studio), take the idea of the Xerox and update it for our age. In fact, one work in the new series, “Signifier 1,” 2016, which also features her hands, includes a scan of one of those early Xeroxed images.

The scans stopped me in my tracks because of the way Smith is able to tease out so much human grace from such a chilly technology, but also for the ways in which they record aging — specifically, by a woman. It’s a topic Smith has taken on in the past. In the 1981 piece “Birthdaze,” she revisited her interior states (psychological and erotic) in a performance that marked her 50th birthday. That work included a tantric ritual and a motorcycle. (Making me realize that my 50th birthday party, in retrospect, may have been lacking.)

Women, for centuries, have been the subject of art — one shaped by the male gaze. Their perceptions of their own bodies, especially as they age, are far less covered. Smith’s scans reminded me of the drawings that New York painter Ida Applebroog made of her own genitalia around the time she turned 40. There was something tender and honest about those. Just like there is a tender honesty to Smith’s images of her own hands: hands that have spent a life making, and reveal a vibrancy yet.

"Holy Squash: Jibz Cameron, Jackie Rines, Barbara T. Smith"

Where: Cirrus Gallery, 2011 S. Santa Fe Ave., downtown Los Angeles

When: Through Jan. 8; the gallery is observing regular hours, except for New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day, when it will be closed.

Info: cirrusgallery.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.