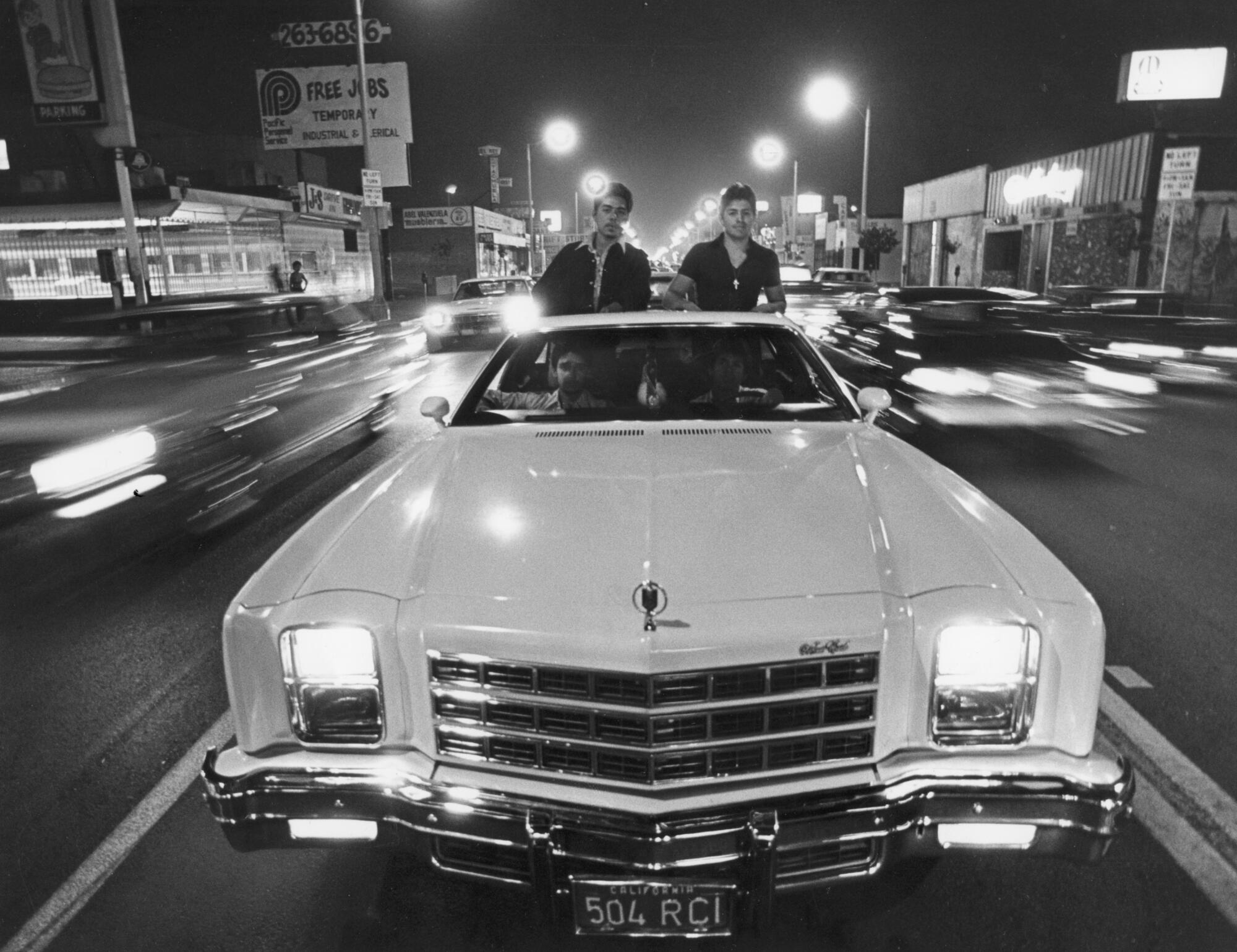

Have you noticed? Every weekend, caravans of lowriders and custom cars are cruising and hopping in a resurgent ritual. Van Nuys Boulevard is one of the city’s oldest sites of this resilient SoCal obsession.

EVERY CAR WORTH showing off has a story.

Consider Mike Molina’s powder blue 1972 E-100 Econoline Ford van, which he inherited after his father and then his mother died during the early months of the pandemic. Parked on Van Nuys Boulevard, the in-process remodel looks a bit out of sorts, not quite as polished as the other lowriders and vintage cars drifting by. But it emotes a certain character, in the way a well-loved car often does.

“It’s a rare find, because it’s a shorty box, no windows.” Molina says of his father’s van. “So in his memory, I’m keeping it. It runs perfect.”

Molina is one of dozens of car lovers drawn to Van Nuys Boulevard for a long-running cruise night. It’s a monthly meetup of lowrider and custom vehicle owners but also a street party. Onlookers post up on the sidewalk, sometimes with folding chairs and coolers. The sounds of funk, freestyle and R&B oldies ooze loudly from passing cars. Masks are mandated, at least on the fliers. Sometimes people get up and boogie. Cruising is back in a major way all around Southern California.

“It’s culture and it’s history, because my dad used to cruise Van Nuys Boulevard in this van,” says Molina, 52, who also reliably blasts music for the cruisers. “And then I saw the Van Nuys cruise night open up again.”

The custom of leisurely drives on urban boulevards in dropped and dolled-up vehicles never really left, but cruising is reaching heights not seen since the heydays of the 1980s and ’90s, according to interviews with car owners, law enforcement officials, neighbors and aficionados across SoCal.

The famed photographer choses his favorite films and TV moments that include that pop culture icon, the lowrider.

Somehow, despite the awful toll of the coronavirus on Latinos in L.A. County, the cruising phenomenon has ratcheted up even further in the last year, police and participants say.

Call it a function of collective boredom during months of stay-at-home orders. Social-distancing guidelines in the last year have also made vehicle caravans the new normal for birthdays, protests, graduations and funerals.

Love of culture

LONA AND ED Aguirre drove to the Van Nuys cruise night from Antelope Valley in her “baby” — a tangerine and pearl white 1951 “Shoebox” Ford sedan, with suicide doors and a creamy leather interior.

“It’s a full custom. Everything’s been touched,” Ed says of his wife’s car.

She can also drop her vehicle. “It’s a hidden button,” Lona says. “We have six grown children, so I needed a toy.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

She watches as several vehicles on the boulevard hop up their front tires, using custom hydraulic compressors activated by a switch. The cars bounce on the asphalt, practically defying gravity at the top of each arc. People on the sidewalk cheer and take videos or photos to share instantly on social media.

“It’s all about fun,” says Lona, 56, “the love of the cars, the love of the culture.”

But there are other shifts. The iconography of West Coast-style vintage lowrider cars is embedded all over popular culture, from films to music videos, video games, museums, marketing and even the digital NFT art world. SoCal-style lowrider adherents flourish in Japan, Brazil and Europe.

Artist Mister Cartoon and King Foo, the secretive social media impresario of Foos Gone Wild with 1.3 million Instagram followers, talk Chicano art NFTs and the future of art shows.

“Pretty much everything in lowriding has flipped around,” says L.A. director and photographer Estevan Oriol, a leading lowrider documentarian. “I would say right now is the third biggest wave in lowriding. The past five to 10 years, there’s been a resurgence.”

A generational shift

ARMAN UTUDZHYAN, standing on the sidewalk on a Saturday night for another Van Nuys cruise, marvels at how much has changed on the streets of Los Angeles since he first got into the scene. Violent crime, despite persistent spasms, is still dramatically lower today than the clatter of violence that once characterized large regions of the L.A. basin.

“Back in the ’80s, they used to jack you for these cars,” says Utudzhyan, who belongs to the Majestics car club and owns a wrecking yard in Sun Valley.

Indeed, with a glint of pride, he remembers the night he survived an attempted carjacking of his 1984 Cadillac coupe lowrider. “They couldn’t take it.

“Shoot me, then,” he told his assailants that night in Hollywood in 1988. So they did.

Utudzhyan, now 49, survived the incident with a permanent indentation in his calf, which he confirms by pulling up a pant leg.

And now he drives something arguably a little better.

His 1960 Chevrolet Impala lowrider, painted verde chiaro, an earthy and inviting green, has the sheen of a trophy. Admirers seem magnetically drawn to it when it is parked.

Today, Utudzhyan is trying to get younger motorists interested in the craft of maintaining a vintage vehicle, so he’s building a new lowrider with a nephew.

“He’s 16. I got a Cadillac for him. Keeps him busy, gets him out of trouble,” the lowrider says.

A love-hate relationship

VAN NUYS Boulevard and the San Fernando Valley are part of a constellation of historic nodes of lowrider culture in Southern California. Though Lowrider magazine ended its print run last year, by the time the once-revered title hung up its hat, the web and social media had stepped up with easy networks for car clubs to get together.

Lately, cruises or lowrider meetups happen every weekend across the region, from Oxnard to Riverside, San Diego to Lancaster. The fountainhead of the culture remains Whittier Boulevard in East Los Angeles, a place that is almost treated like a shrine for SoCal lowrider clubs.

“I hear people saying lowriding is making a comeback. It’s never gone,” says Juan Ramirez, a member of the Just Memories Car Club and an organizer with the Los Angeles Lowrider Community coalition.

But he acknowledges that fresh popularity is drawing people to the cruises with no cars to show off at all. “A lot of people are starting to adapt to this culture,” Ramirez says. “It’s crazy now.”

The car club gatherings have also been drawing other types of vehicles driven by a younger set of motorists influenced more by the “Fast and the Furious” franchise than the 1979 barrio classic “Boulevard Nights.”

Last summer, Ramirez and his coalition of veteranos had to call off the East L.A. cruise night centered on Whittier Boulevard because other motorists were swarming the surrounding parking lots and residential streets. The gathering returned in late August after local leaders negotiated among car clubs, residents and law enforcement in East Los Angeles.

Official L.A. has had a love-hate relationship with the culture for generations. Law enforcement and city governments have long sought to crack down on the practice, with the issue frequently making front-page news in The Times.

In 1985, the paper noted frustrations that cruisers, locked out of Van Nuys and Whittier boulevards by enforcement measures, were meeting in Elysian Park, drawing as many as 2,000 vehicles at a time, largely young people and “almost exclusively Latino.”

“It’s essentially a problem of migration,” the paper quotes a Rampart Division captain at the time, Frank Patchett, who states a fact that sounds as true to last week as it does to four decades ago. “Cruising is a tradition, and if the cruisers get yanked out of one area, they’ll just go somewhere else.”

Late last month, the Sheriff’s Department once again had to break up the cruising crowds in East L.A., which reportedly reached 1,000. On social media, motorists sometimes seek out unofficial announcements of backup cruise “spots” if police clear a certain area, and the gatherings resume.

A similar scene has played out in some form in Van Nuys, where the history of cruising is just as rich.

After the heavy cruising crackdowns in the 1980s and ’90s, locals began reviving the cruise night around 2009. The gathering fell off again a few years later, then picked up steam once more with the help of Martin Jimenez, 35, a dedicated organizer via Facebook and the son of an old-school cruiser, Martin Maciel Jimenez.

“It’s been packed the last two years,” the younger Jimenez says from the sidewalk, where he monitors the cruise with his father and co-organizers. “And you don’t just see Mexicans. You see Armenians, African Americans, Persians. It’s mixed, and we all get along together.”

Sometimes even Danny Trejo or Mister Cartoon cruise by.

As Los Angeles was set to enter the orange tier, a salsa dancing scene emerged on Venice Beach. In these late pandemic days, it’s a sign of renewal.

Despite the pandemic’s winter surge in Southern California, the Van Nuys cruise nights seemed to intensify in December and January. At the time, the cruise was taking place on a fat stretch of the southern portion of the boulevard, mostly facing brightly lighted car dealerships and auto shops between Oxnard Street and Burbank Boulevard.

All last year, organizers say they implored motorists to respect the boulevard. “Don’t burn out those spots,” Jimenez and multiple car club leaders urged.

But there was only so much they could do. Younger crowds, many with newer car models, were gathering at supermarket parking lots, then scattering, chased away by patrol cars. Neighbors near the gatherings reported racing on narrow residential streets, burnouts and even threats to locals who’d go outside and complain.

Fed-up residents were left with the impression from authorities that police were understaffed due to last year’s budget cutbacks.

They turned to City Council member Nithya Raman, a recently sworn-in progressive, whose district stretches wildly through the middle of the city and includes Van Nuys Boulevard. The district office staff met with neighbors, and law enforcement met with car club members and cruisers.

The parties agreed to relocate the semiofficial local cruise about a mile north, to a commercial stretch of Van Nuys Boulevard near Van Nuys City Hall. There, they could loop at will between 5 and 10 p.m. every third Saturday of the month.

Complaints dropped. The cruise night was saved.

Police ask for perspective.

“People try to associate the street racing with cruising, and it’s not quite the same crowd,” says Capt. Andrew Neiman of LAPD’s Valley Traffic Division. “The mentality is very different. The car club cruisers want to show off their cars, and it’s all about the work they put into the cars. And the illegal street racers are all about street racing and doing the burnouts.”

But, he admits, “with the reductions with personnel to the department, we’ve been really challenged to handle 100% of the traffic collisions.”

Neiman is also a native of the San Fernando Valley. He says his cousins participated in the cruises on Van Nuys Boulevard when he was growing up. “People would cruise slow. You’d park. You’d hang out with your buddies,” Neiman says with a chuckle.

The same impulse draws cruisers young and old today, Jimenez says. He and his co-organizers often stay after the cruising is over to clean up Van Nuys Boulevard themselves.

“Most of the guys out there cruising have families already,” he says. “They did long-term time, they’re Christian. They changed their lifestyle, so they’re just trying to live their life now.”

A deep history

AT STREET LEVEL, lowrider clubs are deeply respected organizations. In the Valley, names like Primeros, Dedication, Wild Bunch, Integrity and Viejitos are akin to lowrider royalty. Each vehicle represents decades of meticulous expertise in automatives, and each is a palette for self-expression, says Denise Sandoval, a professor at Cal State Northridge and a veteran researcher and curator on lowrider culture.

“Lowriding is about firme cars, yes, but it’s the people around or inside the cars that are just as important,” Sandoval says.

Some saw a cruise one night and never turned back.

In 1970, Arthur Monarque returned from military service in East Asia and landed at a sister’s house in the Estrada Courts in Boyle Heights. A nephew first took him to Whittier Boulevard to see the cars cruising. “The Mexicans were all dressed Ivy League, continental and had cars, and I was like, ‘Wow. The Chicanos I was looking for,’” Monarque recalls.

Soon after, Monarque moved to the Valley and joined the scene there. “At that time,” he says, “I had two ’64 Impalas and one 1951 Deluxe two-door hard-top.”

Back then, he says, the cruise for people who loved cars happened on Wednesdays. Valley cruisers met up at burger stand parking lots, where they exchanged details about house parties for the upcoming weekend.

“So they would cruise, pass around word of mouth, before cellphones,” he says, and the process repeated.

Now 72, Monarque still lives in the Valley and shows up regularly to the cruise nights and car club meetups at local parks. He also noticed the buzz in interest during the pandemic.

“They got to get out. They’re frustrated at home. And that’s what cruising does. You get out,” he laughs.

The Carranza family worked on the McGrath Family Farm for more than 20 years. Just as they sought to go into the strawberry business on their own, the coronavirus hit.

Cruising in some form has been popular in the Valley likely since the first U.S. teenagers got their hands on their own wheels, maybe as early as the 1930s, says Kevin Roderick, author of “The San Fernando Valley: America’s Suburb.” Van Nuys was also one the earliest boulevards in the city to get street lighting, he notes.

“Customizing and hot rods were a very big thing in the postwar San Fernando Valley,” Roderick adds. “There were lots of wide open streets to race on. Everybody had a garage where they could tinker with an engine or invent a new paint design, and Van Nuys Boulevard provided a public arena for showing off your creation.”

Oriol, the photographer, says that at a basic level, the dropped, slow-rolling automobile will always remain a renegade, even if brands and marketing firms bank on its imagery. “Any lowrider is a moving violation, right off the bat,” he says. But, he notes, “I get pulled over now by cops who want to take selfies of the car.”

Today, both police authorities and car club cruisers say relations are better than they’ve ever been. Car clubs often team up with police stations for toy drives and fundraisers. “I remind them I appreciate them,” says Kristan Delatori, the senior lead officer of the area that includes Van Nuys Boulevard and who helped negotiate the change in location for the local cruise.

Part of the shift is about the big-tent nature of the scene. The Aguirres identify as Christians and are respected as lowriders in their Lancaster community. Cruising may never totally shed its previous connotations, Lona Aguirre says, but it’s no bother to them.

“We both lived in the gang life. I’m tattooed all over,” she says. “But they have no idea that I own a school, my husband is a chemist. It’s a judgement. ... We love what we do. This is who we are.”

On a cool spring evening, the lowriders return. Dropped Cadillacs and Impalas. Modified pickup trucks and vans blasting rap. Every so often, there are vintage cars, or pre-1960, that are referred to affectionately as “bombs” or “bombas.”

There are even a few hot rods, customized to look like they just rode off a nearby studio set for a talkie. They all ride slow, windows down. Up and down, north and south, for hours.

Sometimes the inspiration strikes and the lowriders start hopping. No police came by for most of this night, except for the occasional requests to get pedestrians with cameras out of traffic lanes.

The new location seems to be fitting along fine with the regulars, says Joey Smith, 55, as he watches with his car club, Los Primeros.

“You know, you can three-wheel, hop, but once you start holding up traffic and spinning in the middle of the street, then it kind of creates problems,” Smith says.

He grew up in Sunland and Tujunga and now lives in Chatsworth. He is driving a 1964 Impala SS, painted cobalt blue. It was his father’s. “We always wanted him to join a club, but he never wanted to join a club,” he says.

Smith also inherited a vintage automobile after his dad died.

“I put a new motor in it, put air-ride [suspension] on it, and I joined the club,” he says. “It’s got a 350 motor, 360 horsepower. You can see the rest. It’s just beautiful.”

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.