Column: What to do about the Golden Globes?

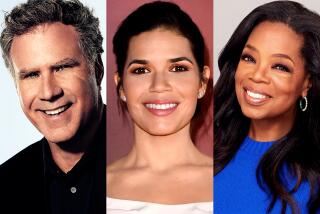

Promos for the Golden Globes always tend toward the irreverent and self-mocking, but this year an exchange between hosts Tina Fey and Amy Poehler seems even more pointed than usual. “The stakes have never been lower,” says Fey. “If we play our cards right, it might be the last awards show ever!” answers Poehler.

They could be referring to the audience appeal of a virtual telecast in this second pandemic-plagued year, but in light of a recent Times report about the Hollywood Foreign Press Assn. and its practices involving the Globes, the co-hosts might also simply be stating the unavoidable truth.

Now that certain damning facts have confirmed long-held suspicions, how are we even supposed to watch the Golden Globes?

Last week, Times reporters Stacy Perman and Josh Rottenberg published an investigation into the HFPA that revealed a small, self-selected and self-protective group that continues to use its awards ceremony as a cash, perks and access cow for its seemingly arbitrarily anointed members.

According to the report, relatively few of the 87 people who vote on — and profit from — the Globes write regularly for major overseas outlets (though many are paid by the HFPA to write for the HFPA website and sit on HFPA committees). Indeed, living in Hollywood, or Los Angeles, seems to be a much more significant prerequisite for membership than being an actual working journalist, which makes sense considering that the kind of perks HFPA members regularly enjoy would be forbidden by most legitimate media outlets.

If you, like many others, have been wondering how, exactly, “Emily in Paris” got so many nominations this year — even as the blazingly original and affecting “I May Destroy You” got none — a lavish Paramount-paid event in pre-pandemic Paris for 30 of the 87 HFPA members could provide an answer.

If you, like many others, have also been wondering why none of the many fine Black ensemble movies made the Globes’ best film nominee lists, the revelation that not one of the HFPA members is Black could provide that answer as well.

A Times investigation finds that the nonprofit HFPA regularly issues substantial payments to its members in ways that some experts say could skirt IRS guidelines.

When The Times’ report came out, this last revelation was seen by many as the most damning. Indeed, early reaction to systematically documented instances of what appeared to be, at best, perilously wobbly journalistic ethics and, at worst, blatant pay-to-play schnorring was disturbingly dismissive.

“We already knew about the HFPA,” was a common refrain. “That’s why no one takes the Globes seriously.”

This is patently ridiculous. Maybe not the “we already knew” part but certainly the “no one takes the Globes seriously” part.

By whatever measure you choose to employ — money, energy, media attention, television viewership, the recruitment of Fey and Poehler — many people, including millions of viewers (18.3 million in 2020), take the Golden Globes very seriously.

Like other big awards shows, it is a huge money-maker. Not just for the HFPA, but for everyone involved or professionally engaged with the event. In a normal year, that includes the portions of the local economy catering to all the hotel, limo, restaurant, flower, alcohol, gift bag, publicity and extraneous specialty shopping needs of the visiting nominees and their entourages.

Obviously, the Globes is highly profitable for NBC, which regularly touts the telecast’s annual audience as being larger than the Emmys’ and just shy of the Oscars’.

The event also brings a stream of advertising dollars to any media outlet that covers Hollywood, including this one.

The organization said the perception that many members are not serious journalists is “outdated and unfair” and that it is committed to addressing the lack of Black members.

Even as traditional ad revenue has dried up for many outlets, awards season remains a reliable spigot, if perhaps less gushing than it once was. Readers and viewers care about film and television, and in the ever-splintering landscape of film and television, Hollywood creators care even more than they once did about awards that are not named Emmy or Oscar (they have always cared about these). A Golden Globe may not be as prestigious as an Oscar, an Emmy or a guild honor, but an award is an award, and awards invariably lead to increased credibility, more opportunities, higher salaries and, for those who work in publicity, bonuses.

Studios and streamers do not have special awards teams, and awards budgets, just because it’s fun to get dressed up for a couple of nights.

More important, the HFPA wisely times its nominations and telecast as a precursor to the guild awards and Oscars. This allows the group to position the Globes as predictive of the Oscars (even though they very often are not). More important, it offers everyone an elongated awards season, with more time and an extra, fancy platform.

The longer everyone has to plug their project, the more For Your Consideration ads the studios will buy. Which is why so many media outlets that a decade or so ago snootily eschewed hyped-up awards coverage now have special sections with fancy pull-out covers, awards correspondents, photo booths, red carpet reporters and all manner of awards-centric video projects.

All of which includes the Golden Globes.

So when blame is assigned for the inordinate amount of influence this small and ethically-challenged group has amassed, the media must take its fair share, including the same Times that just exposed the scandal.

Being the hometown paper of Hollywood, The Times has long offered extended and extensive awards coverage. For years, many of our pieces about the Globes have inevitably reminded readers that Globes are voted on by a very small group that not only has a reputation for boorish behavior during screenings, but also has been dogged by scandals involving ethics and transparency.

The HFPA’s troubles began in 1958 when former HFPA President Henry Gris resigned from its board on the grounds, according to a Variety article from that year, that certain awards were being given out “more or less as favors”; the issues continued in 1968 when NBC refused to air the awards after the FCC found that the broadcast misled viewers as to how the winners were chosen. (After major changes in the voting process, the Globes returned to NBC in 1974.)

Still, The Times, like every other outlet, has continued to cover the bestowing of the trophies — analyzing the choices, reviewing the telecasts and often finding the, er, spirited atmosphere of the show a welcome contrast to the more staid Oscars.

We’ll be covering them this year as well, although given the findings of our reporters, not to mention the limitations of the pandemic, that coverage will no doubt be different in content and tone.

But what will or should the future bring?

The fallout over the HFPA’s lack of Black members continues publicly and behind the scenes.

Despite more than a few calls for everyone in Hollywood and the entertainment media to ignore the Globes in the hopes that the HFPA will just go away, it’s hard to imagine a cancellation of the telecast. Revenue generation aside, the night is a popular, well-ensconced part of awards season, and an often diverting few hours of television.

Although the link between extravagant courting and certain nominations seems impossible to deny, most of this year’s nominees produced fine work that deserves acknowledgment. Likewise, the lack of Black-led films in the Globes’ top film categories seems directly linked to the lack of Black HFPA members and recalls the #OscarsSoWhite campaign in response to similar Oscar nomination lists for similar reasons.

It also recalls the many aggressive steps the film academy has taken to rectify its own historical lack of diversity, and many, including The Times’ editorial board, are recommending that the HFPA follow a similar path. Indeed, days after the report was published, the HFPA announced that it would “immediately work to implement an action plan” to bring in Black members as well as members from “other under-represented groups.”

The HFPA, however, has larger problems to fix as well. Fortunately, the solution to pretty much all of them is so simple that it comes down to two words: Go legit.

The Golden Globes is a mainstream event and the group behind it needs to start behaving like it. Harvey Weinstein is in jail, and the ethos of lavish-to-the-point-of-bribery Oscar campaigns that he ushered in has long been dust. No doubt being catered to with special access and fabulous events has been loads of fun for the HFPA membership. But if that boondoggle culture doesn’t come to an end immediately, the Globes will mean less than those participation trophies everyone regularly gets into a snit about. Participation trophies at least go to all the players on the team, not just the ones whose parents let the coach borrow their Colorado condo for the weekend.

No A-lister wants a participation trophy that the studio had to buy. Even if it comes with a weekend of hanging out at the Four Seasons and the chance to wear earrings borrowed from Harry Winston.

If the HFPA wants to be taken seriously, if it doesn’t want this year to be — as Poehler suggests — the last Globes ever, it needs to do what the film academy has done: grow and diversify transparently. Journalists who cover the entertainment business for publications outside the United States do not have to live in Los Angeles to be considered part of the Hollywood press; much of Hollywood itself doesn’t work or live exclusively in Hollywood.

As the entertainment industry becomes increasingly international, it would be interesting, and valuable, to see what sort of work is prized by a diverse, experienced and respected group of journalists and critics from outside this country. That kind of award could actually help Hollywood as it grapples with its ever-shifting landscape, and might actually reflect the world as it is captured by a wider array of film and television makers.

Especially if those journalists understand that when you have to get a present to give a prize, you’re not a member of an awards body. You’re an awards dealer.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.