It appeared to be a moment of triumph in the long, tumultuous story of the Hollywood Foreign Press Assn.

In November, a federal judge sided with the HFPA — the tiny, 87-member group of international journalists that doles out the annual Golden Globe Awards — in dismissing a potentially damaging antitrust lawsuit.

The suit was filed three months earlier by a Norwegian entertainment journalist who had been denied membership in the group. It had drawn widespread attention in Hollywood, where the HFPA wields outsize power as the arbiter of one of the entertainment industry’s most important — if often mocked — awards. And to the HFPA, it represented a direct threat to that power.

In her suit, Kjersti Flaa accused the HFPA of institutionalizing a “culture of corruption,” claiming the tax-exempt organization operated as a kind of cartel, barring qualified applicants — including herself — and monopolizing all-important press access while improperly subsidizing its members’ income. The group, Flaa asserted, was rife with ethical conflicts, with members accepting “thousands of dollars in emoluments” from the very same studios, networks and celebrities they conferred trophies upon, all of it hidden behind a “code of silence.”

After the Times investigation and mounting criticism in Hollywood, how will the HFPA and the Golden Globes move forward?

Following the judge’s dismissal — partly on the grounds that Flaa didn’t suffer economic or professional hardship as a result of her exclusion from the association — HFPA attorney Marvin Putnam of Latham & Watkins said the group had been vindicated, calling the suit nothing more than “a transparent attempt to shake down the HFPA based on jealousy, not merit.”

Within the HFPA, however, Flaa’s suit had struck a nerve with some members who had hoped it might force the organization to make what they see as long-overdue changes.

“The dismissal was disappointing,” said one current HFPA member, who like many quoted in this article declined to be identified out of fear of retaliation from others in the group. “I thought it would shake things up…. We are an archaic organization. I still think the HFPA needs outside pressure to change.”

Over its nearly eight-decade history, the HFPA has weathered a string of embarrassing scandals, lawsuits and often blistering criticism of its membership. The group has been the butt of jokes even from the stage of its own awards show. Hosting in 2016, Ricky Gervais dismissed the Globes as “worthless,” calling the award “a bit of metal that some nice old confused journalists wanted to give you in person so they could meet you and have a selfie with you.” In a 2014 interview, actor Gary Oldman said the group was “90 nobodies having a wank” and called for a boycott of the “silly game” their awards represent.

The hardest-working person at Sunday night’s Golden Globes ceremony may have been whoever was in charge of the bleep button.

Yet despite all this, the HFPA has managed to carve out a unique and improbable position of influence. Its members — relatively few of whom work full time for major overseas outlets — are routinely granted exclusive access to Hollywood power players, invited to junkets in exotic locales, put up in five-star hotels and, as Globes nominations near, lavished with gifts, dinners and star-studded parties. To the studios, networks and celebrities that court its favor and exploit its awards as a marketing tool, the group is at once fawned over, derided and grudgingly tolerated. (Four years after blasting the HFPA, Oldman thanked them when accepting his first-ever Globe for his turn as Winston Churchill in “Darkest Hour.”)

In recent years, the HFPA has worked to rehabilitate its public image. It has given away millions of dollars to various causes supporting the arts and journalism — more than $5 million in grants were awarded in 2020 — while endeavoring to bring the historically loose and boozy Globes ceremony a new measure of respectability.

But in the run-up to the 78th Golden Globe Awards ceremony slated to run Feb. 28, questions persist around the insular association’s legitimacy, the qualifications of its members and its ethics.

Interviews with more than 50 people — including studio publicists, entertainment executives and seven current and former members — as well as court filings and internal financial documents and communications, paint a picture of an embattled organization still struggling to shake its reputation as a group whose awards or nominations can be influenced with expensive junkets and publicity swag.

The Times’ investigation also found that the nonprofit HFPA regularly issues substantial payments to its own members in ways that some experts say could run afoul of Internal Revenue Service guidelines. HFPA members collected nearly $2 million in payments from the group in its fiscal year ending in June 2020 for serving on various committees and performing other tasks — more than double the level three years earlier.

“It’s a beautiful idea to take the money from NBC and give it to good causes like tuition and to restore films,” said one member. “But there is a spirit now to milk the organization and take the money. It’s outrageous.”

As the HFPA grapples with thorny internal issues, this member described the group’s monthly membership meetings as “a war zone.”

In response to questions posed by The Times, an HFPA representative said, “None of these allegations has ever been proven in court or in any investigation, [and they] simply repeat old tropes about the HFPA and reflect unconscious bias against the HFPA’s diverse membership.”

The association said “all active members have to present clippings every year as part of the robust reaccreditation process” that is reviewed by Ernst & Young.

Regarding the increasing payments to the organization’s members, the HFPA representative said, “Our compensation decisions are based on an evaluation of compensation practices by similar nonprofit organizations and market rates for such services” and are “vetted by a professional nonprofit compensation consultant and outside counsel, where appropriate.”

As for fears among some reform-minded members that they could face retaliation for speaking out, the representative said, “The HFPA obviously does not condone bullying or retaliation by members.”

The organization said the perception that many members are not serious journalists is “outdated and unfair” and that it is committed to addressing the lack of Black members.

The HFPA, which has a reputation for making occasionally head-scratching choices when picking Globes nominees and winners, has faced further criticism for this year’s slate of nominations, which did not include several Black-led Oscar contenders such as “Da 5 Bloods,” “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” and “Judas and the Black Messiah” in the nominees for the group’s top award. Several other picks this year befuddled critics and Oscars prognosticators — including a best motion picture nod in the comedy or musical category for pop star Sia’s widely panned directorial debut “Music” — heightening the sense that the HFPA is out of step.

Even as some members argue for reforms within the group, Flaa says she and other foreign journalists intend to keep pressing the HFPA to address what they see as its unfair and improper practices. After the court rejected her claim that the HFPA was a quasi-public organization, Flaa’s attorney filed an amended motion to the suit, with Spanish journalist Rosa Gamazo now joined. The case is pending.

“This has been going on so many years and it’s still going on,” Flaa said. “It’s time for them to realize they need to change.”

The Globes have long been seen as the Oscars’ more frivolous cousin — or, as Gervais more scathingly put it while hosting in 2012, “what Kim Kardashian is to Kate Middleton.” But while NBC promotes the event as “Hollywood’s Party of the Year,” to the studios and networks, the awards have become serious business, and millions of dollars are spent annually wooing the group that hands them out.

While ratings for other awards shows have trended downward in recent years, the audience for the Globes telecast has generally held steady at 18 million to 20 million viewers, easily outpacing the Emmys and narrowing the gap with the Oscars. To the studios, that audience represents a potential marketing boon for hopefuls on the road to the Academy Awards, to be held this year on April 25, investing the HFPA with a power beyond its minuscule size.

“There is a spirit now to milk the organization and take the money. It’s outrageous.”

— HFPA member

“I think the Globes are honestly the most important moment leading up to the Oscars — and when you think that such a small group makes those decisions, it’s kind of horrifying,” said one longtime film publicist who like many interviewed for this article declined to be named out of fear of offending the group. “The real problem is the studios need them.”

The association launched in 1943, when 23 foreign entertainment correspondents banded together to gain traction with the studios. The group debuted the Golden Globes the following year at a luncheon on the Fox lot, and the awards, which eventually grew to encompass both film and TV, brought clout.

But as the HFPA’s profile rose, so did questions of legitimacy and accusations of impropriety. NBC dropped the Globes after the Federal Communications Commission found in 1968 that the awards broadcast “substantially misleads the public as to how the winners were chosen and the procedures followed in choosing them.” The HFPA changed its procedures, hired the accounting firm of Ernst & Young and “vowed to clean up its act.”

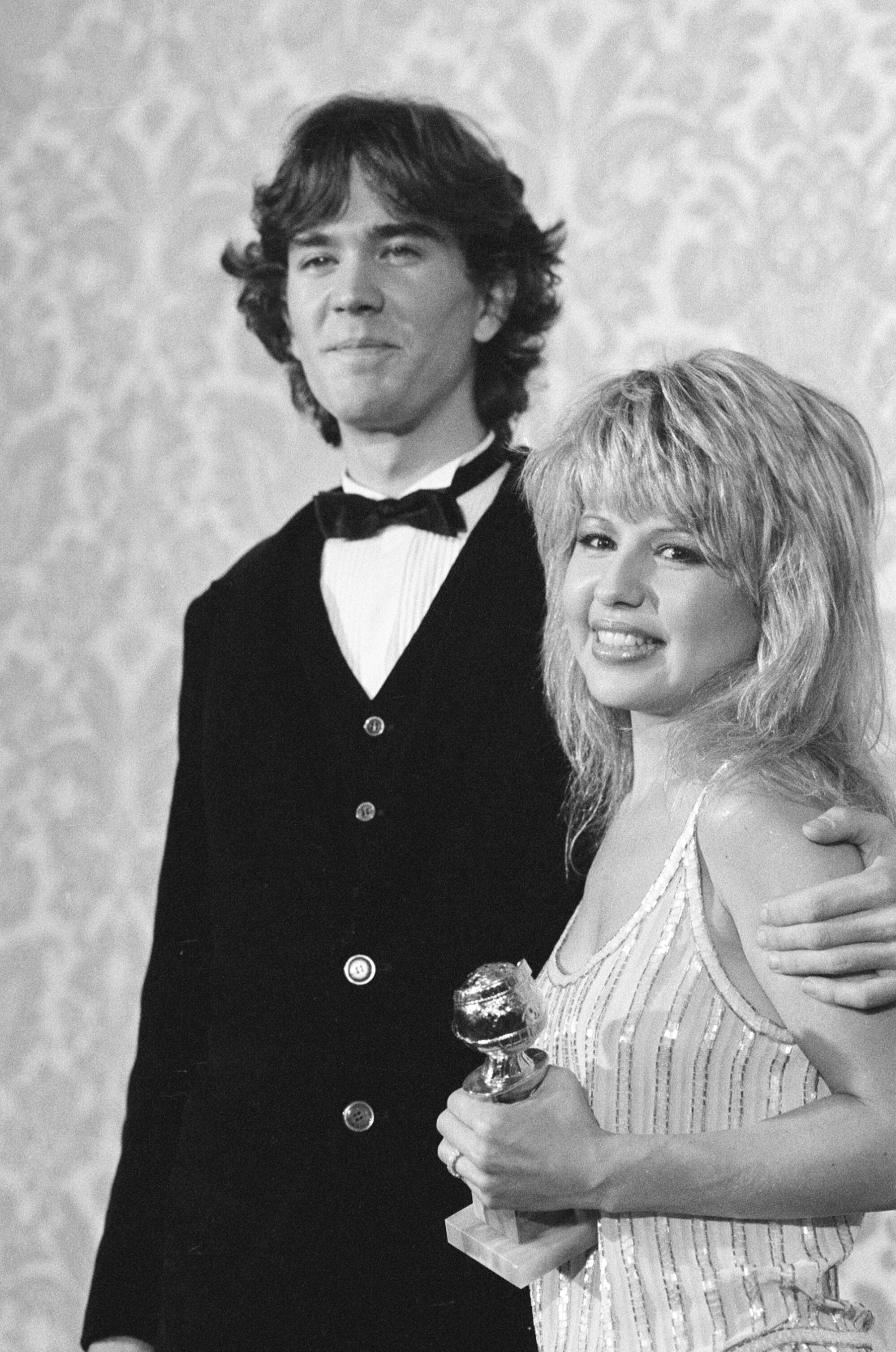

But controversy continued. In 1982, actress Pia Zadora was awarded a Globe for “new star of the year in a motion picture” for her performance in the critically lambasted film “Butterfly.” Just weeks before voting, HFPA members had been flown by Zadora’s husband, producer Meshulam Riklis, to his casino in Las Vegas. CBS, then in its second year of airing the ceremony, dropped its broadcast deal with the HFPA.

Much of the Globes’ success can be attributed to its partnership with Dick Clark Productions, which came on board in 1983. The show’s ratings took off after the broadcast switched from cable station TBS to NBC in 1995.

In the years since, HFPA members have frequently been portrayed as celebrity-obsessed freeloaders, exchanging votes for perks and access and undermining any notion of journalistic credibility — allegations detailed in various stories, most notably a 1996 Washington Post piece by Sharon Waxman titled “Fool’s Gold.”

Facing increased scrutiny, in 1999 HFPA members were forced to return 82 Coach watches valued at more than $400 apiece that had been given to them by USA Films as part of a campaign to try to score Sharon Stone a Globes nod for her work in the film “The Muse.” (USA Films said the studio got the watches for free and didn’t realize how expensive they were. Stone earned her fourth nomination for her performance but did not win the Globe that year.)

In 2011, the HFPA’s longtime publicist, Michael Russell, filed a lawsuit alleging that members accepted money, vacations, gifts and a host of perks “provided by studios and producers in exchange for support or votes in nominating or awarding a particular film.” The complaint further alleged that members sold access to the Globes by peddling credentials to other media for space on the red carpet. The HFPA countersued and said the claims were “without a shred of evidence.” The suit was settled in 2013.

The HFPA has in recent years sought to burnish its public image in large part by donating millions to a variety of entertainment charities and scholarships, such as USC’s School of Cinematic Arts and the Film Foundation and more recently the Committee to Protect Journalists. In 2019, the group partnered with The Times and other journalistic organizations in the first-ever L.A. Press Freedom Week, a series of panels and conversations around the protection of the 1st Amendment.

At the same time as it has boosted its philanthropy, insiders say, the HFPA has been directing some of its funds to benefit its own members.

The HFPA’s contract with NBC has ballooned in recent years. Last fiscal year, the organization pulled in $27.4 million from the network, up from $3.64 million in fiscal 2016-2017, according to a budget document. As of the end of October, the HFPA had just over $50 million in cash on hand, internal financial documents show.

“Annually, the Globes is among the highest-rated non-sports programs on NBC,” the HFPA representative said. “What we are paid by NBC reflects the value of the Globes in the market.”

Even as the Globes has brought millions into the group’s coffers, the once robust field of international entertainment journalism upon which the HFPA was founded has shrunk considerably, putting new strains on some members.

“A lot of these people, I’d be surprised if they can even make a living anymore,” said one person who has had extensive dealings with the HFPA. “Interviews with Robert Downey Jr. or Angelina Jolie don’t have much value these days. So there is this striking disparity: They’re not rich and they can’t sell their stories for much money, but they are hobnobbing with celebrities and staying at nice hotels and going to parties.”

As that disparity has widened, some members say the association has become less a torchbearer of Hollywood to the wider world than a private retirement cushion for older members and a reliable income stream for nearly everyone else.

In the fiscal year ending in June 2020 the HFPA paid $1.929 million for members serving on committees and performing other tasks. The amount was budgeted to increase to $2.15 million in the current fiscal year ending in June 2021, according to financial records reviewed by The Times.

By the end of 2020, the association was collectively paying nearly $100,000 a month to members serving on more than a dozen different committees. Members often serve on more than one committee, records show.

Two dozen members on the foreign film viewing committee in January each received $3,465 to watch foreign films, according to a monthly treasurer’s report. There is a travel committee that pays those on it $2,310 a month to control the budget and approve membership excursions (despite the pandemic-era halt on travel, payments continued throughout 2020). Members of the film festival committee and the archives committee earn $1,100 and $2,200 a month, respectively. Former presidents and other members are paid $1,000 a month to serve on the history committee.

The film and television academies, by comparison, offer no such remuneration to their members.

“We are mindful of the unprecedented economic challenges facing our employees due to the effects of the pandemic,” the HFPA representative said. “The HFPA is committed to maintaining the continuity of our skilled and experienced workforce to ensure our future success, and will continue to compensate them for the range of services they provide to the organization.”

HFPA members who want to participate on committees without payment have been dissuaded from doing so. At least one member was told by another that “serving without [being paid] makes it harder for the rest of us to get paid.” Some members decline to serve on committees, and thus don’t receive those fees.

Additionally, members received a total of $585,000 in the fiscal year ending June 2020 for contributing articles to the HFPA’s website and doing other web-related jobs, more than double the level from four years earlier. Members who moderate news conferences receive $1,200 a month to do so, according to a monthly treasurer’s report.

“The website has become an extremely important source to generate income,” said one current member. “If you write eight articles, you can get close to $3,000 a month. But if you spend any time on the website, it’s not that impressive.”

The HFPA asserts that it has expanded, redesigned and improved the quality of its digital offerings.

Even the HFPA’s charitable activities have become a source of compensation.

Last October, the annual grants dinner — usually a glitzy affair at a luxury hotel with celebrity presenters, the time when the association announces its philanthropic disbursements — was held virtually. Three members earned $8,000 each for working at the event last year, financial records show.

The HFPA has six paid staff members but also compensates its board members. Five board officers made between $63,433 and $135,957 in the tax year ending June 30, 2019, according to the most recent tax filings publicly available. Four officers are set to receive bonuses — from $3,604 to $9,016 — for their work in putting on this year’s virtual Globes ceremony, according to an internal financial report. Board directors earned between $22,915 and $78,079 in the tax year ending June 30, 2019, according to tax filings.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is substantially bigger in terms of members and assets and has a paid staff, but it does not pay its eight officers or the 54 governors on its board.

“Relative to the HFPA’s revenues and charitable contributions, its employment-related expenses are modest,” the HFPA representative said.

But some tax experts questioned the scope of payments to members and whether they were appropriate for a tax-exempt organization.

“It’s unusual that all of these people are getting paid,” said Daniel Kurtz, a partner at New York-based law firm Pryor Cashman and an expert on nonprofit and tax-exempt organizations.

This particular kind of tax-exempt organization — a trade organization — “exists to advance the profession or industry,” Kurtz said, “not the interests of the individual members. Lots of organizations run afoul of the IRS on precisely that issue.”

“Trade associations are supposed to operate for the benefit of their industry and not to specifically benefit their members,” said Douglas Varley, an attorney with the Washington, D.C.-based firm Caplin & Drysdale, who specializes in tax-exempt organizations. “So if the association is paying its members for these services, it has to be receiving services of commensurate value that all go to advantage the interests of the industry.”

Money began flowing to members in greater amounts about 10 years ago as the journalism industry contracted. There had always been a small number of committees that members were paid for serving on, but some began to complain that the same few members benefited from serving on them.

According to two current members, the growth of both committees and the associated financial remuneration took off during the 2011-2012 term of then-President Aida Takla-O’Reilly, who campaigned on the promise to increase benefits for members. Subsequent presidents continued the practice. Takla-O’Reilly did not respond to a request for comment.

The COVID-19 pandemic has only increased the urgency to funnel more money to members. Before then-HFPA president Lorenzo Soria died in August, members and others familiar with the HFPA recalled, he mentioned feeling under pressure to tap the association’s resources to help members.

One individual recounted a conversation last summer with Soria in which the multi-term president said: “I have no choice. They call me every day for more money.”

In a text exchange between Soria and this member, reviewed by The Times, the two discussed surfacing old HFPA news conference transcripts with stars such as Robert Mitchum and Paul Newman on the website under the banner “HFPA Classics Interviews.”

“It’s one of the ideas i had There will be others,” Soria wrote. “And yes I have members asking for financial relief. This way would be legal Money in exchange of a service.”

Last March, when the pandemic shut down Hollywood, the HFPA established an emergency fund for reporters of $125,000 to be administered through the L.A. Press Club.

In April, during a monthly membership meeting, Soria said many HFPA members received checks from the L.A. Press Club grant, according to a recording from the meeting obtained by The Times.

When asked whether he had thoughts on the topic during the meeting, Gregory Goeckner, the HFPA’s chief operating officer and general counsel, said: “I actually think it’s important that we really not know this in detail; it helps us defend it from a tax point of view…. The closer this gets to the members actually knowing who got money, it just makes it difficult for us to defend.”

The HFPA said it did not place conditions on who received the Press Club grants other than that the funds go to journalists in need.

In recent years, members say, the HFPA has come up with new financial vehicles to support the group. It has added new committees and in some cases added more spots on existing ones.

“Member payrolls,” January’s membership meeting notes said, “continue to run above budget.”

The HFPA representative said “certain HFPA members provide services to the HFPA that are outside of their role as members and are fairly compensated for those services” and noted that such compensation decisions “are based on an evaluation of the market rate for such services paid by similar organizations.”

Still, some within the group find the trend problematic. “One day they will create a committee to create more committees. It’s a never-ending story,” said one member. “We are a nonprofit, not a bank.”

In addition to their work as journalists, some HFPA members also engage in a variety of professional activities that critics say could violate the group’s bylaws and policies.

Over the years, according to insiders, some members have been known to pitch their own projects to actors and producers. In 2017, the HFPA instituted new rules aimed at curbing potential conflicts of interest. When they vote for the Globes, members must disclose conflicts, which are evaluated by Ernst & Young, the HFPA said.

For members to vote, NBCUniversal requires that they certify they are in compliance with the Communications Act of 1934, which prohibits the practice of “payola,” the undisclosed acceptance of payments in exchange for an on-air promotion or service.

According to Russell’s 2011 lawsuit, HFPA members accepted “payment from studios and producers for representing films and lobbying other HFPA members for Golden Globe nominations and awards for these films.”

“I’d say a small group of us realize that we need to change in order to survive. It’s about taking ourselves seriously so that we can be taken seriously in Hollywood.”

— HFPA member

One marketing veteran who has worked on several Oscars and Globes campaigns told The Times they experienced this kind of overture, saying three different HFPA members had over the last decade offered to pay this individual $5,000 to $10,000 to lobby other members to vote for a particular film. The marketer said they refused the offers, the most recent of which was in 2015.

“I sometimes joke with producers about how much it would cost to buy a nomination,” said the marketing vet.

An individual close to this person recalled being told about these efforts, saying they “definitely thought it was unsavory.”

“We have no evidence that this is occurring and would take any specific allegations very seriously if any were ever made,” the HFPA representative said of such claims.

Under the organization’s bylaws, members who do paid work in any capacity for a broad spectrum of entertainment, promotion or publicity firms are ineligible to serve as elected officers or directors.

Helen Hoehne served as an HFPA director between July 2012 and June 2019 and became the group’s board vice president in September 2020.

Her LinkedIn profile states she was creative director of media and public relations firm Upgrade Media until August 2020.

In a November 2019 email that Soria sent to a member, the late HFPA president cited a conversation with Laurent Puons, the head of the Monte-Carlo Television Festival, in which Puons confirmed that Hoehne had worked with him in recent years.

“We started in 2017 and they have been very helpful they helped with celebrities,” Puons said, according to the email. “And they are helping with the prince Albert event in February here in Los Angeles.”

A representative for the festival declined to comment. Hoehne also declined to comment and referred questions to the HFPA. The representative said Hoehne and another HFPA member worked with talent at the festival but did not handle publicity.

“As part of that conflicts process, these potential conflicts were disclosed to the HFPA and vetted, and the HFPA concluded that the individual brands that they consulted for at the time did not present a conflict,” the representative said.

Questionable choices and “Music” and Ryan Murphy? Even a consistently off-base organization like the HFPA can get it right sometimes

Given the negative attention the HFPA has so often received, one might ask why Hollywood continues to not only tolerate the organization but actively empower and celebrate it.

Winning favor with a tiny pool of fewer than 90 HFPA voters is far easier logistically than tackling the film academy’s 10,300 members, of whom roughly 9,400 are eligible to vote on the Oscars, or the more than 25,000 members of the Television Academy. And while the HFPA has rules forbidding the acceptance of gifts valued at more than $125 per project, there is a widespread perception that members can still be wheedled and swayed with special attention and access to A-list stars with whom they can take selfies to post on Instagram.

“Because there’s so few of them, they make a nice target,” said one longtime awards consultant who declined to speak on the record because they still work with the group.

The HFPA says that it vigorously polices its policies around the perks that its group receives, noting that, although its members receive hotel stays, dinners and other freebies, the group pays for its own airfare to overseas junkets and strictly enforces its policy regarding gifts, which it updated in late 2019.

Still, one case that drew notice among this year’s Globes nominations highlights the questions that continue to arise about the group’s care and feeding when awards are involved.

In 2019, more than 30 HFPA members flew to France to visit the set of the new series “Emily in Paris.” While there, Paramount Network treated the group to a two-night stay at the five-star Peninsula Paris hotel, where rooms currently start at about $1,400 a night, and a news conference and lunch at the Musée des Arts Forains, a private museum filled with amusement rides dating to 1850 where the show was shooting.

“They treated us like kings and queens,” said one member who participated in the set visit. (Other non-HFPA media also separately visited the show’s set, including a freelance contributor to The Times who interviewed the show’s creator, Darren Star.)

Last month, “Emily in Paris,” which debuted on Netflix and became an enormous hit for the streamer despite middling reviews, received two Golden Globes nominations including best television musical or comedy series. Though the HFPA has a history of favoring light, European-set fare, the nomination for best series nevertheless surprised some TV insiders who hadn’t considered the show a serious awards contender. One of the show’s own writers, Deborah Copaken, wrote in an op-ed that she was stunned that a frothy show about “a white American selling luxury whiteness” was nominated while HBO’s acclaimed limited series “I May Destroy You,” which deals with the aftermath of rape and knotty questions of race and class, was shut out.

One HFPA member says the show’s best series nod points to a broader credibility issue for the group. “There was a real backlash and rightly so — that show doesn’t belong on any best of 2020 list,” said this member, who did not attend the junket. “It’s an example of why many of us say we need change. If we continue to do this, we invite criticism and derision.”

Representatives for Paramount Network and Netflix declined to comment.

For publicists, an entire financial incentive structure has grown around securing Globes nominations and wins. A redacted 2017 contract for an awards consultant reviewed by The Times detailed what a source said was a typical pay scale for a studio Globes campaign. In addition to the consultant’s $45,000 fee, they would receive a $20,000 bonus if the film earned a best picture nomination and $30,000 if the film won.

A former Amazon Studios marketing executive, who declined to be named because they continue to work in the industry, said that the streamer retained a dedicated team of half a dozen people solely to work with the HFPA.

HFPA members “live for the events, rather than for the love of movies — it’s more about how you’re treating them,” said the source, who added: “You had to have nice receptions in elegant places. If you didn’t do that, you’d hear complaining that it wasn’t great. They were vocal about it.”

The Hollywood Foreign Press Assn. failed to nominate the HBO limited series, praised for its deft handling of sexual assault, or its creator/star.

Over the years, the HFPA has managed to survive numerous scandals that could have felled it. In the official program for the group’s 75th anniversary celebration in 2018, then-President Meher Tatna acknowledged the group’s checkered history. “We were thrown off the air, then brought back on again. There were tangles with the FCC. We were pariahs one year, then things went back to normal the next…. There has been good press and bad. We are still here.”

But amid a renewed barrage of criticism, some within the organization say the HFPA faces an uncertain future unless it finally addresses the issues that have bedeviled it for so long.

“I’d say a small group of us realize that we need to change in order to survive,” said one of the reform-minded members. “It’s about taking ourselves seriously so that we can be taken seriously in Hollywood.”

Others argue that the HFPA is ultimately a creature of Hollywood’s making and that, as long as the industry continues to profit from the awards they hand out, little is likely to change.

“If the studios wanted to kill the Golden Globes, they could overnight,” said one source who has worked closely with the HFPA. “But everybody likes getting an award, and with the money and everything that comes with a show of that magnitude, it’s like a snowball you can’t stop.”

Times staff writer Glenn Whipp contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.