What would Baldessari do? A good question for the end of a terrible year

“What would Picasso do?”

That’s a question that artist John Baldessari asked a few years ago, in his typically sardonic, deceptively simple way. He asked it in the manner that he asked a lot of questions over the course of his long life, by making it a work of art: Plain black letters are stamp-printed on a small white card, a bit of writing whose words prompt speculative pictures to form in your mind.

Artists are canaries in the culture’s coal mines, sensitive to otherwise imperceptible shifts in social posture and gaping voids in consciousness. Art is soft power, exerting its persistent force in a harsh and indifferent world where hard power reigns.

For most of 2020, I have found myself wondering something similar. The Picasso question implies the need to respond to a predicament, and the year has been choked with those. Over and over, as the months rolled by and the sorrows grew, I wondered: What would Baldessari do?

The president of the United States was impeached for abuse of power and obstruction of Congress, then given a pass by his party’s senators despite overwhelming evidence of guilt. Mass death arrived from a pandemic, an apocalyptic health crisis mismanaged with virtually criminal negligence.

Calamitous economic ruin was visited upon millions, thrown out of work through no fault of their own and abandoned by their government. Food insecurity became widespread.

“Lockdown,” with its ethos of the jail cell, entered the daily vernacular. As stay-at-home orders were issued, the crushing cruelty of homelessness visible on Los Angeles’ streets got worse, not better, witnessing a double-digit increase over the year before.

Through summer months the nation erupted in disgust over unceasing police brutality, which finally made the festering sore of systemic racism impossible for Americans to ignore. For decades we’d been hearing that we desperately needed to have a national conversation on race and, now that we were finally having it, forces of reactionary violence loomed.

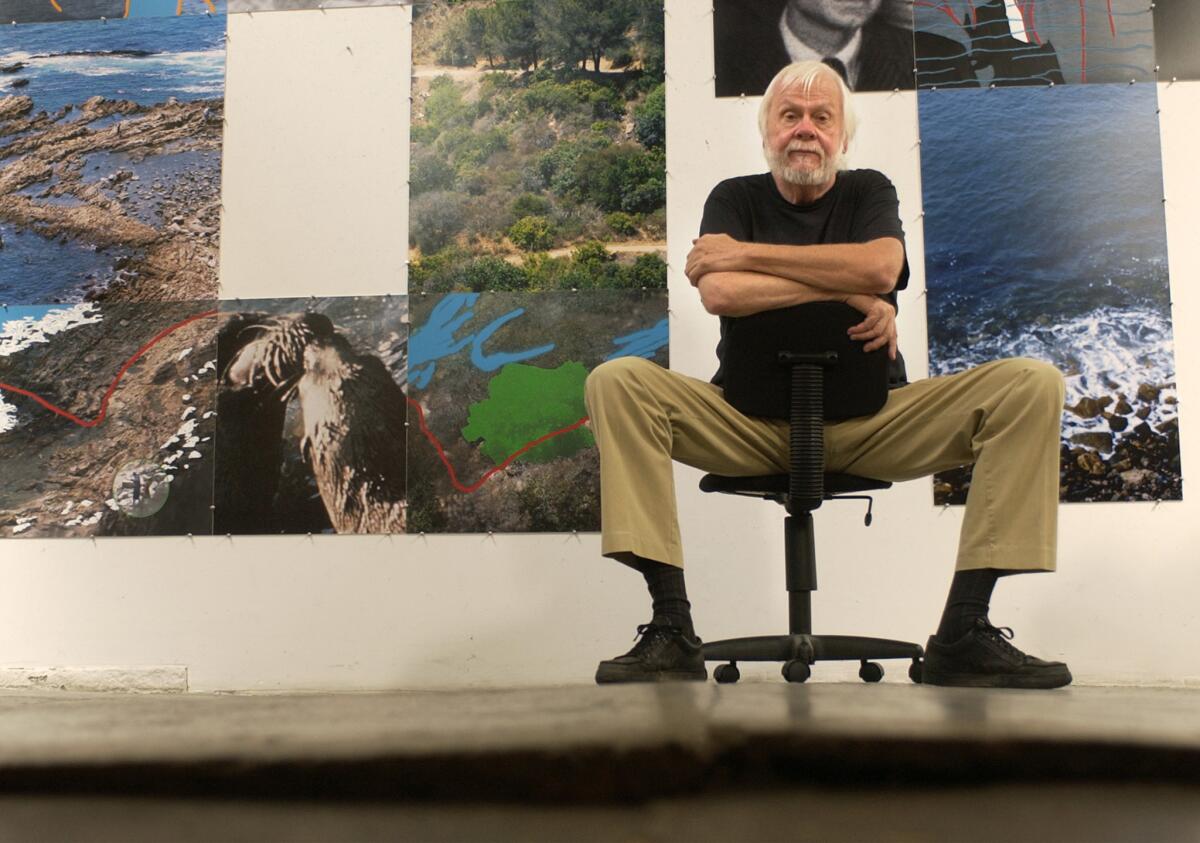

In the face of all this, I wondered what Baldessari would do because the awful year had begun with the artist’s loss. On Jan. 2, Baldessari died at the ripe age of 88.

He had been a central fixture of the city’s cultural life for so long — roughly half a century, the era that saw L.A. emerge from backwater to global art capital — that it seemed just about impossible to be without him. Amid the sadness, I remember thinking at the time that it was just like John to wait until the day after New Year’s to depart, so as not to spoil anyone’s holiday fun.

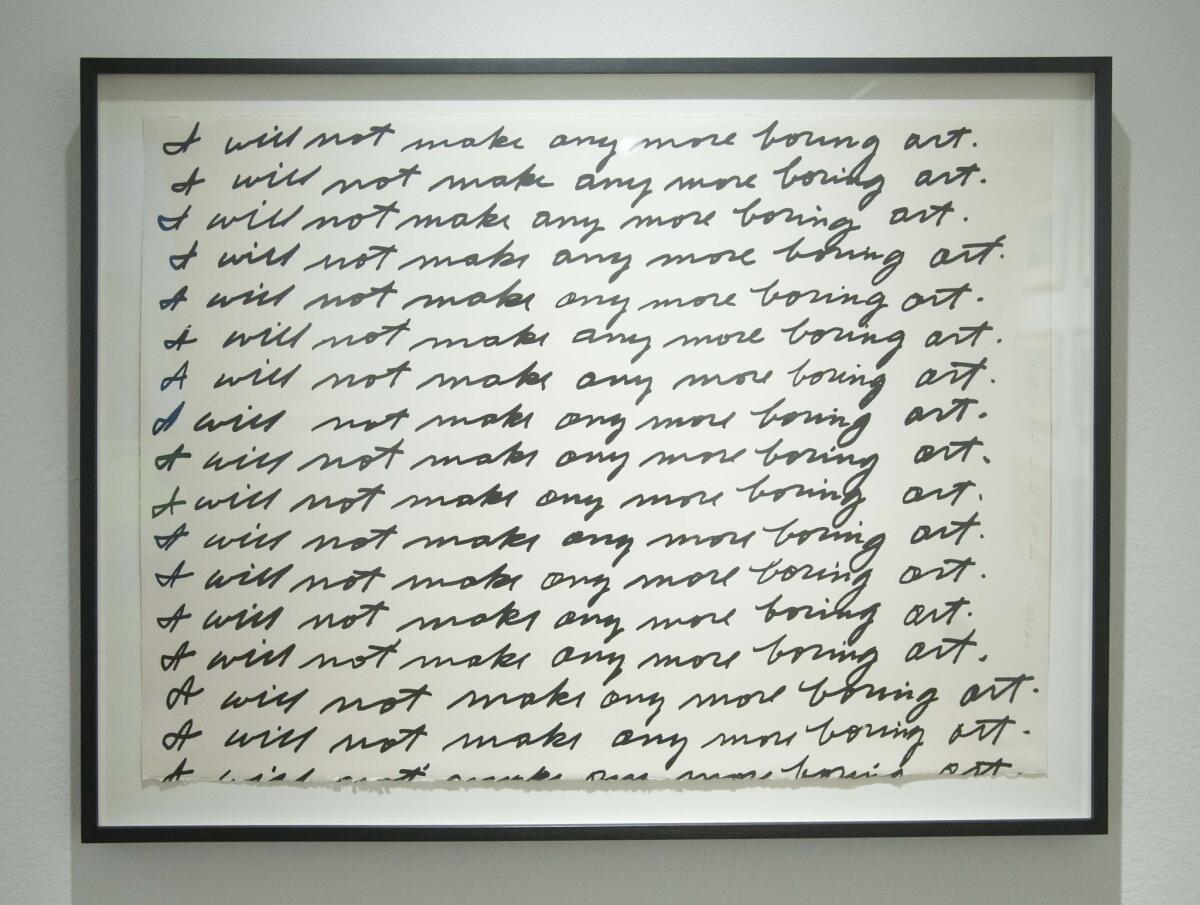

Generosity of spirit is a hallmark of Baldessari’s work. It formed the scaffolding for his famous 1971 pledge to never again make boring art. Why visit tedium on an audience?

Often overlooked is the genesis of that anti-boredom vow. It came in the form of a mural.

The Nova Scotia College of Art and Design was emerging as one locus for the new international genre that would come to be called Conceptual art. The school, however, didn’t have the funds to fly in Baldessari, foundational Conceptual artist, from 3,600 miles across the continent at his CalArts faculty perch in Los Angeles. So, instead, he gave instructions by phone that NSCAD students should make the art for him: Pull out markers and write “I will not make any more boring art” over and over, directly on gallery walls.

Like any elementary school punishment, the instructions were meant to ingrain a point of view in young and aspiring artists. Unlike an elementary school punishment, breaking rules rather than following them was being valued.

Often unnoticed: Marker on walls is different from erasable chalk on slate. Those kids covering gallery walls with art in Nova Scotia were unwittingly making a mural.

Conceptual artists were the latest in a long line declaring easel painting dead. It started with French painter Paul Delaroche in 1840 and exploded with Americans like Donald Judd and Frank Stella in the 1960s. But, like Conceptualist Sol LeWitt in 1969 mapping out mind-bending wall drawings, long live murals.

Baldessari loved easel painting — he started out making them — and he was no stranger to murals. He was born and raised south of San Diego in National City, just a dozen miles from the border with Mexico. All over Mexico and Southern California, murals are a familiar, democratically minded art with an impressive history. People speaking publicly through art is the political dimension that makes murals tick.

Some insist that politics is inimical to art, but politics is merely the assorted set of systems by which we organize our social lives together. Art is among them. Ordering up a long-distance mural by telephone removes the hand of the artist as singular marker of art’s value, substituting his brain instead. A mural declaring “I will not make any more boring art” is cultural politics writ large.

The lettering in Baldessari’s question about Picasso is neatly stamp-printed rather than written out by hand in cursive script. (The “no more boring art” mural was also soon turned into a printed lithograph.) The format slyly acknowledges his own inheritance from the Spaniard: Picasso introduced printed language into painting in a big way a century ago, when he added bits of text clipped from daily newspapers to his Cubist still lifes.

At the same time, Baldessari’s impersonal stamp lends a degree of anonymity to his sheet. It looks impersonal and objective. The artist disappears, removing himself as an authoritative voice speaking from above to supplicant viewers below.

We all know who Picasso was, more or less, so the whole culture — all of us — seems to ponder the question of what he might do.

Best of all, Baldessari’s question slices and dices received wisdom with rapier wit. It plays off the establishment rise of the Christian right in the 1990s, a pernicious phenomenon in American politics that has driven the malevolent culture wars. On wristbands and bumper stickers, the self-righteous crowd piously pondered, “What would Jesus do?” — all while pretty much flouting everything the biblical Jesus did and didn’t espouse.

In part, Baldessari’s querying joke is funny because he did something similar.

Conceptual art partly arose from pushing aside the settled convention of Picasso’s central place in the temple of Modern art, king of the early 20th century hill. Since the late 1950s, adventurous artists had been replacing Picasso’s influence with that of Marcel Duchamp, master of visual puns. Baldessari’s semiserious, stamp-printed jest surreptitiously bumped aside the Cubist painter being named.

Beyond a committed art public, of course, Dada punster Duchamp’s name wouldn’t ring many bells. One of the great things about Baldessari’s art is that it stays true to a democratic inclusiveness. All a viewer needs for access to his Picasso jape is the ability to read simple English. Yet the more you know about art, the more you have explored its extraordinary, enlivening histories, the deeper and more philosophically dense the imaginative joke gets.

Something for everyone.

The last lengthy conversation I had with Baldessari came at the unveiling of a witty new work called “Fake Carrot” (2016). A nearly 7-foot-tall orange vegetable topped with a cascading crest of feathery green fronds was suspended on a wire from a sleek overhang above a swimming pool at the Venice home of architect Kulapat Yantrasast. The artist, already in ill health and unable to walk without help — no mean feat, given his towering 6-foot-7-inch frame — sat quietly on a bench to one side.

As usual, he was grinning. He was cautiously glancing around, as artists often do at the opening of a show, anxious to see how the new work was being received.

What made this gigantic, artful carrot “fake,” it seemed to me, wasn’t merely the obvious plastic materials from which it is fabricated. (Who would mistake a colossal carrot for “real”?) What made it worth emphasizing as ersatz was its status as a stand-in for the artist himself, an outsize figure whose ungainly stature — 6 feet 7! — the dangling object not coincidentally evoked.

As artists’ veiled self-portraits go, this one is spot-on. Art is a carrot, not a stick, the smile-inducing sculpture insists — an inducement for contemplation and, sometimes, even a sweet bribe for tolerance and understanding.

Could it have been made anywhere else but Southern California? For a century the place has been the national dangling carrot for American dreamers.

Wondering what Baldessari would do in the face of 2020’s relentless onslaught of brutalities might seem foolish or strange, but finally it’s comforting. What he would do, just like Picasso — and Duchamp and thousands more before and after him — is get busy making art.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.