For living proof of the determination and persistence required to conquer the art world, consider Magdalena Suarez Frimkess. Her artistic talent, first noted by nuns when she was 9 and living in a Venezuelan orphanage, has brought the painter and sculptor her first major museum retrospective — at age 95.

For decades, this force of nature has made a daily ritual of manipulating earth, water and fire to create perfectly imperfect stoneware dishes, bowls, teacups and vases as well as animal and cartoon character figurines. Using her own made-from-memory glazes and stains, she painstakingly renders an idiosyncratic visual language: flowers, Aztec pictograms, Japanese patterns, classic Popeye and Felix the Cat and Mickey Mouse comics, even one of her recent CVS prescription labels. Her deft brushwork, dazzling sense of color and unpretentious approach transform her humble, charming ceramics into artworks that captivate the eye and engage the heart and mind.

“I am very sloppy. I do it quickly and let it be, and some pieces come out better than others,” declares Suarez Frimkess, who prefers the understatement and deadpan humor of her favorite comic strips to art world pontification. “But doing the work keeps me alive no matter what.”

And in a manner fitting the artist, she concludes: “I did OK.”

Already collected by fellow artists Cindy Sherman and Kaws, director Sofia Coppola and music mogul Benny Blanco, and having produced two collaborations with Italian fashion house Marni, the plain-spoken ceramist is doing decidedly better than OK. She’s the subject of her first museum retrospective, “Magdalena Suarez Frimkess: The Finest Disregard,” which runs through Jan. 5 in the Resnick Pavilion at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Composed of 178 works, the exhibition features never-before-seen drawings, paintings and ceramics from 1970 to today. It also includes collaborations with her husband, Michael Frimkess, 87, who created towering wheel-thrown vessels in classical shapes that she decorated with a mash-up of autobiographical and pop cultural imagery.

“The more you look at her work, the more you see personal histories, mythologies, cultures and media, all interwoven into a totality of human experience,” says Michael Govan, chief executive and director of LACMA. “And it’s all brought down to this delicate pinch of the fingers with clay and small lines made by quivering energetic hands.”

Reflecting on the subtitle of the show, curator Jose Luis Blondet observes that what is distinctive about Suarez Frimkess’ work “is her finest disregard for almost everything, including technique. Her work is intentional and incorporates whatever crosses her mind.”

Depicting the Venice canals, Hollywood toons and herself riding a BMX bike (which she is said to have done into her 80s), he adds, “she has a strange ability to connect to the cultural life of the city, and she occupies a space in the imagination of younger artists.”

Seen, perhaps, as a response to 21st century digital overload, Suarez Frimkess’ hand-wrought creations have long looked fresh to generations of art lovers who would become increasingly obsessed with ceramics. Her work was spotted by The Times in 2003 at the now-defunct Little Tokyo Clayworks, a gallery where acclaimed ceramic artist Karin Gulbran first encountered the magic of Magdalena.

“I was blown away by her incredible sense of design, how she uses a very tiny brush to make little lines that keep the glazes separated, similar to the look of cloisonné,” Gulbran says. She purchased a mug sculpted into a face and signed “Magdalena” for $60 (similar works now can fetch thousands of dollars at auction) and spread the word among her artist friends.

Over the next two decades, Magdalena fans came to include a crop of L.A. art stars, including gallerist Ryan Conder, ceramists Gulbran and Shio Kusaka, sculptors Ricky Swallow and Evan Holloway, painters Mark Grotjahn, Jennifer Guidi, Lesley Vance and Jonas Wood.

Swallow, who says Suarez Frimkess “definitely played a part in establishing a resurgence of pop sensibility in ceramics,” included her in a group show in L.A. at David Kordansky Gallery in 2013 and exhibited alongside Magdalena and Michael at the Hammer Museum’s “Made in L.A.” biennial in 2014. Gulbran curated a 2014 solo show in New York City, and Wood has paid tribute to her in his own work, including a rendering of the 55-inch-tall Asian-style lidded jar “Mercado Persa” that appears in the LACMA exhibition.

“This is a show you have to see in person,” Swallow insists. “You don’t want to be the fool who said you saw it on Instagram.”

Suarez Frimkess is too well educated to be considered a naive or outsider artist, and her love of cartoons and consumer goods is too sincere to be considered Pop Art, like the practitioners of the 1960s, who were making a commentary on consumerism and society, Govan says. “Magdalena takes cartoon characters as a starting point and imagines the possible psychologies and narratives these characters may experience,” he says.

Often the scenarios she creates with toons reveal an “attempt to map the human condition in all its sparkle and grit,” says Swallow, who lent a vase depicting Superman in a wheelchair to the exhibition. Curator Blondet describes a sculptural work called “Chariot” that contains two figurines of Minnie Mouse and one of Popeye in a green cart with pink wheels. “And they don’t have a horse,” he says. “They are stranded. And I find that so profoundly sad.”

Gulbran adds that a lot of the cartoons in Suarez Frimkess’ work have “a severe edge.”

“They’re not cute and funny, they’re very cunning,” Gulbran says. “One of her favorite images is Olive Oyl being dangled over a school of sharks.”

For Suarez Frimkess, comic strip characters are more than mere avatars, they are teachers. “Maybe I am a child,” she says, “but I understand their humor. When you are young, it’s silly. Now that we are grown up, we can see Popeye, Olive Oyl, Snoopy as philosophers. They make fun of everything and know all the answers to life.”

Her favorite is Condorito, a Chilean comic strip based on the exploits of a somewhat lazy but ingenious condor. “He’s been my psychiatrist for many years,” she says with a smile. “He says, ‘Don’t be too serious, just live through it and keep doing what you’re doing.’”

The Norton Simon in Pasadena may get overshadowed by LACMA, MOCA and the Broad, but its 12,000-piece collection is one of SoCal’s best. Our critic offers a shortlist of don’t-miss works.

Her early life story has more of the makings of a telenovela than the Sunday funnies. Born in Maturin, Venezuela, in 1929, Maria Magdalena Suarez Matute moved with her family to the capital city of Caracas, where she lived in one room with her father and two brothers as her mother sought treatment for tuberculosis. After her mother’s death, 9-year-old Magdalena was raised in a Catholic orphanage. Nuns persuaded her father to place her in art classes, where she studied painting and printmaking at the leading art school in Venezuela.

In 1949, she moved to Chile with an older man in the military. “I got pregnant with a married man,” she recalled in a 2021 short documentary, “I had to run away.”

After 10 years and the birth of two children, she returned to school and impressed a series of visiting American professors. In 1962, she received a fellowship for a residency in Port Chester, N.Y. The father of her children told her that if she accepted, she would go alone.

“I paid my price, I can tell you,” Suarez Frimkess says. “I lost my kids and my country.”

During her residency, she met Michael Frimkess, a Los Angeles potter who had studied with ceramic revolutionary Peter Voulkos at what would become the Otis College of Art and Design. She married Michael in Los Angeles in 1964, and by 1971, when he was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, they had set up shop on Abbot Kinney in Venice.

“I have to blame Michael’s family,” she recalls. “His father rented this place that was very cheap in those days and put us to work, and the rest is history. I refused to get into the pottery wheel, that was his thing.”

It was the heyday of studio pottery, and Michael created the pots she could decorate, while she also kept the house, cared for their daughter, Luisa, sold clothes she designed in the front of the studio and made her own work from scraps of clay.

“Magdalena told me it was a boys’ club back then,” says Conder, founder of the Chinatown gallery South Willard, an early supporter of Suarez Frimkess. “And her work was free of the concerns of the art market, so she could just be herself.”

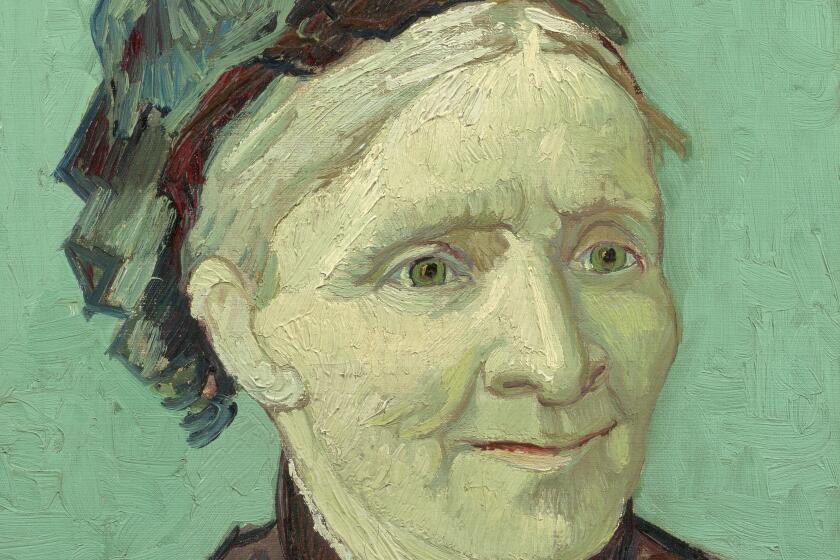

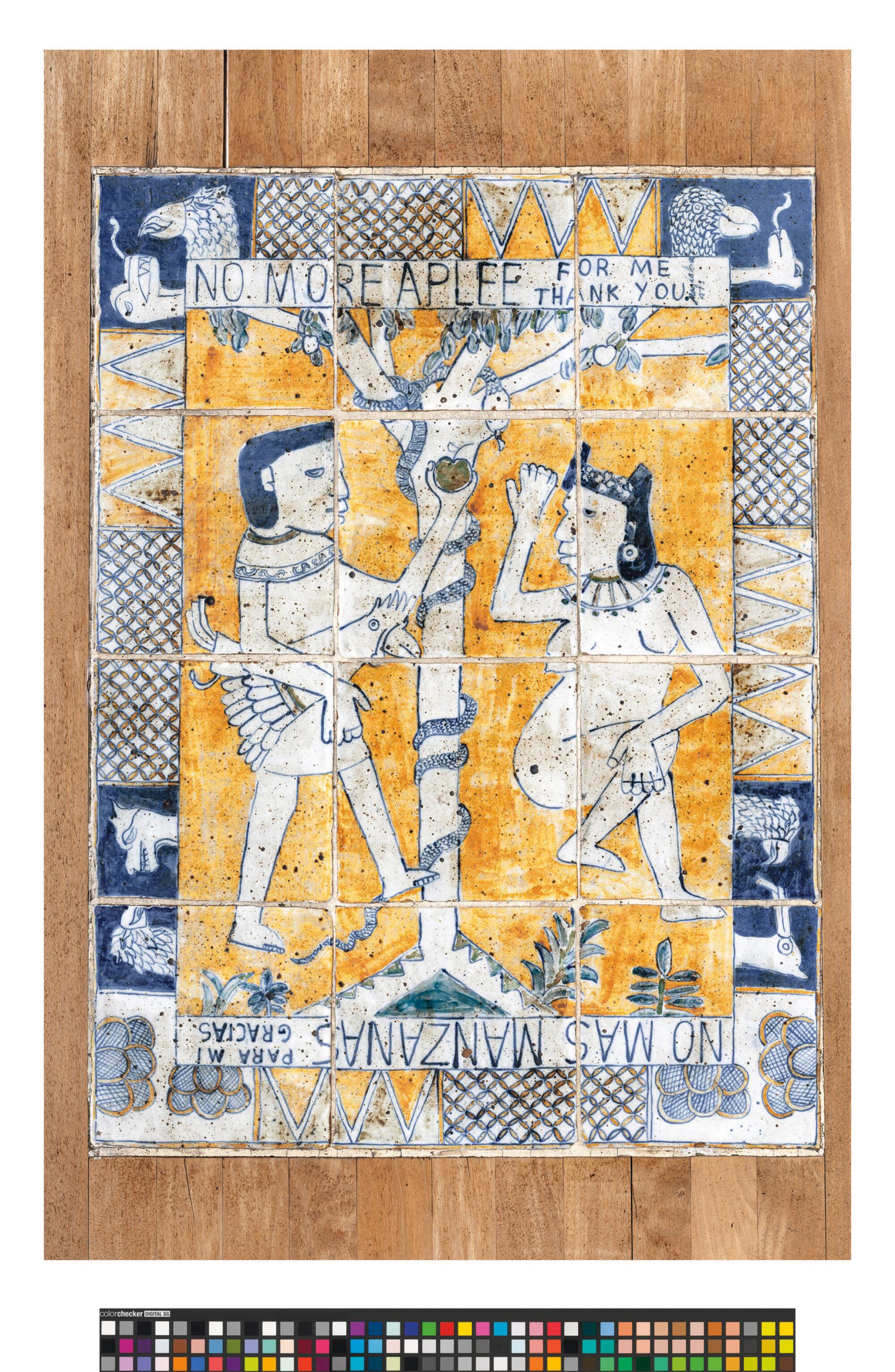

Part of her self-expression leaned toward empowering messages to women, including hand mirrors with reverse sides that illustrate nude Aztec women looking at themselves in mirrors. “One of my favorites is Olive Oyl pulling Popeye by his ears,” Swallow says. “This skinny woman dragging a muscled sailor across the surface of a plate.” The LACMA show includes another example that was published in the journal Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics. That untitled 1973 work is a table inlaid with a tile mural depicting an Aztec couple and the Tree of Wisdom. “I make a joke about Adam and Eve,” the artist laughs. “She says, ‘No more apples for me, thank you.’”

Old tires become artistic totems in the hands of Betsabeé Romero, whose profile is rising thanks to an exhibition timed to the Venice Biennale that will come to Long Beach.

“My mother is a survivor,” says her daughter Luisa Frimkess. (Magdalena brought her two children from her earlier relationship to the United States in the ’70s.) “She’s raw and honest. And she’s proud of the recognition that’s been due her; she’s been hidden behind her husband for many years.”

Though she has said, “it’s about time,” Suarez Frimkess remains mostly modest about her accomplishments. When told that one of her works, a square Orphan Annie box with a horse finial on the lid, recently sold for more than $23,000 at auction, she exclaims, “My God, that’s a lot of money. It kind of surprises me, but that’s the commercial world, and I am not out in that world.”

Since 2014, Suarez Frimkess has been represented by kaufmann repetto, which has galleries in Manhattan and Milan, Italy. “We’ve worked hard to change the narrative of her just being a woman who makes tchotchkes and understood as a resilient and dedicated artist, an exceptional ceramicist and painter,” says founder and co-owner Francesca Kaufmann, who intends to keep up the momentum from the LACMA exhibition.

On Sept. 6, kaufmann repetto in New York City will unveil “Now Girls Allowed,” a solo show; in October, Suarez Frimkess will be included in El Museo del Barrio’s 2024 La Trienal in Manhattan; and a 320-page monograph on the artist’s work will arrive in early 2025. European exhibitions and travel are in the works.

“Before, I took it all so serious, the poverty and misery; now, I have the luxury to put that aside and do the work I love,” Suarez Frimkess says. “I don’t have the energy to go to many places anymore, unless it’s outer space.” She sighs, and then adds with a laugh, “If only they’d invite me.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.