Science + social justice + magic. The spellbinding formula of artist Glenn Kaino

This is what a wish looks like: It is delicate and flickering, luminescent aqua blue. A wish does not sit still. It is restless and searching, continually morphing in shape, an abstract paintbrush swoosh one moment, a speckle of raindrops the next.

Artist Glenn Kaino would like to give you three wishes, each packaged inside a small ceramic disk. His end goal? Bring a little magic into your life and transform the world.

That may sound hokey. But Kaino is decidedly unafraid of hokey — art world hipsterdom be damned.

“I’m trying to create hope,” Kaino says of two new installations — his most significant sculptural works in years.

At his Atwater Village studio, something of a percolating laboratory for art and activism, early versions of the works bubble and whirl inside two tents. They’re collaborations with scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory — one featuring tanks of frozen alcohol vapor, the other a vat of bioluminescent marine organisms — to create magical-seeming effects.

Kaino rushes over to one of them. “Take a look,” he says, lifting the corner of the tent, like an expectant circus ringleader.

Inside “Cloud Chamber,” otherwise invisible particles — protons, electrons, muons and alpha particles — manifest before the naked eye, swirling and sparkling when immersed in the tank’s frozen mist. A teeming mini-galaxy trapped in a fish tank. “Stardust,” Kaino says.

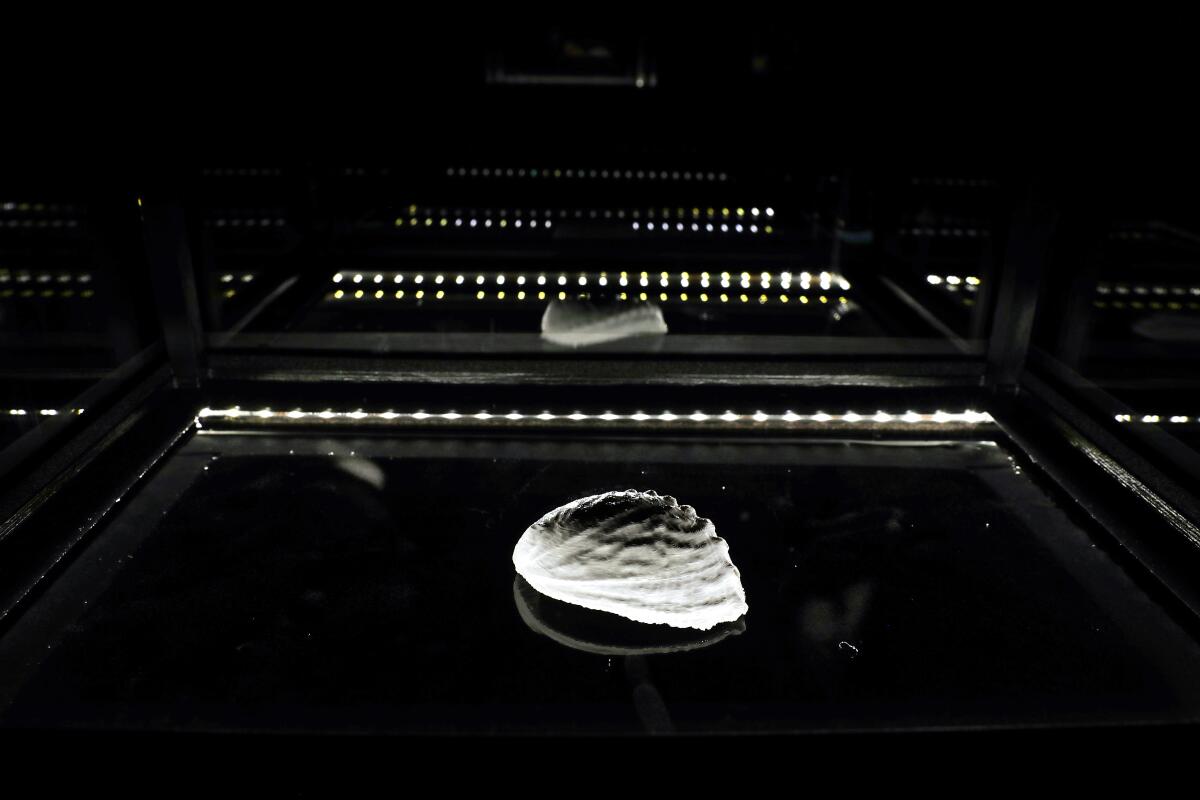

Inside the “Wishing Well” chamber, viewers are meant to toss sculpted coins into a tank of water, disrupting the glowing, aquamarine plankton and creating glittering abstract patterns and occasional explosions of light. Electronic music artists Jacques Greene and Nosaj Thing created the meditative sound bath for both pieces.

“They’re intended to create moments of visibility for things that are invisible around us. Most people don’t feel seen, understood. Making things visible is a form of empathy,” Kaino says. “And the glowing trail — you can actually visualize your wish!”

Kaino’s exuberance is understandable. The artist has a dizzying number of projects coming to fruition, all of them at the center of his interests in social justice, science and the environment, pop culture and magic. “Cloud Chamber” and “Wishing Well” make up an exhibition called “Tidepools,” a 20-minute, immersive solo experience that was intended to debut at the new Long Beach art and wellness space Compound in September, but which has been in limbo because of the coronavirus. Compound hopes to premiere the works in December, pandemic permitting.

A Mass MoCA solo exhibition of four new large-scale installations addressing global protests is planned for February. Several in-progress works for that show lie around Kaino’s studio in different stages of development. Kaino will soon be launching an online magazine called _Ships, featuring long-form articles, interviews, photography and videos from prominent writers and artists, echoing ideas in the Mass MoCA show.

Kaino also co-directed a feature documentary film about sprinter Tommie Smith, who famously raised his gloved fist to protest racism in America at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, where he’d won the gold medal in the 200-meter race. The film, “With Drawn Arms,” co-directed by Afshin Shahidi, premiered Nov. 2 on Starz.

“That image, it’s one of the most powerful protest gestures of the 20th century,” Kaino says of Smith’s raised fist. “And it’s especially relevant now.”

Activism is central to Kaino’s practice. The 48-year-old artist toggles between two-dimensional works, sculpture, installations and multimedia. But activism — mining it conceptually and creating works intended to “spark change” — is a through-line. Often his work takes a phenomenological approach, as the Compound works do, playing with light, color and shadows to toy with viewer perceptions, a skill he honed over a decade studying magic and illusion. Altering viewers’ perceptions in this way is an act of social consciousness: It shows that things aren’t necessarily as they seem, that the world can be a different place, if they so desire.

Collaboration — with other artists, activists, scientists and celebrities — is something Kaino turns to so earnestly and often, it’s practically a material in his artist’s toolbox, as integral as paint and paper. These often counterintuitive partnerships are a form of “conceptual kitbashing,” as he calls it, meaning reassembling disparate elements in new ways.

A more than 10-year partnership with illusionist Derek DelGaudio spawned the art collective A.Bandit and the hit off-Broadway show, “In & Of Itself,” which premiered at the Geffen Playhouse; his performative dinner club, “The MSG Club,” with chefs Niki Nakayama and Carole Iida-Nakayama of n/naka restaurant, has hosted events in L.A., New York and Mexico City; and his media company with actor-activist Jesse Williams, Visibility, will soon launch a Latinx trivia videogame app, Ya Tu Sabes. When talking about his art, Kaino almost always uses “we,” crediting everyone in his six-person studio with the ideas behind the work.

The movie “With Drawn Arms” is the result of an eight-year partnership with Smith, one that spawned multiple artworks and a 2018 exhibition at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, where Smith lives.

“Turning Tommie’s original intention to the happenings of the moment has been inspirational for me, and changed my life for sure,” Kaino says. “It allowed me to understand that there are still ways for us to make contributions to history.”

Kaino didn’t seek Smith out. Like so many of his creative partnerships, it came through chance. Kaino had a black-and-white image of Smith and American bronze medalist John Carlos performing their Black Power salute taped to his computer in his studio. He’d admired Smith since high school, and the image inspired him. One day in 2012, a visiting friend, Michael Jonte, glimpsed it: “Oh, Coach Smith,” Jonte said, referring to Smith’s former job as a track coach at Santa Monica College.

Jonte connected them, and two days later Kaino was on a plane to Atlanta.

After that initial visit, Kaino made a cast of Smith’s arm with fist, which he used to create multiple works, pieces that celebrate Smith’s bravery and illuminate the consequences that the athlete faced afterward. He was banished from the U.S. track and field team and had trouble finding work back home, where he received death threats.

“The gesture was so powerful, it flattened the man who performed it,” Kaino says. “My work was meant to re-dimensionalize the man so we can learn from him.”

That meant Tommie-inspired prints as well as a sculpture of the athlete, “Invisible Man (Salute),” that’s dark aluminum on one side and mirrored steel on the other, so that it seemingly disappears on one side. Kaino’s “Bridge” installation — a 100-foot-long, wave-like suspension bridge with gold-painted resin casts of Smith’s arm — speaks to protests across generations.

All the while, Kaino’s team filmed the visits with Smith and the art-making, footage that’s woven into the documentary. The movie also tells the story of Smith’s origins growing up in Lemoore, Calif., where, as a young boy, he picked cotton to help his family get by. But at its heart, the film celebrates Smith’s 1968 protest, while weaving in historical moments from the ‘60s civil rights movement. Williams appears in the film, as do former President Obama, Colin Kaepernick and the late congressman and civil rights pioneer John Lewis.

Speaking about his Black Power salute now, 52 years later, Smith’s voice chokes with emotion.

“That action, it wasn’t me, Tommie Smith the Black man, up there on the victory stand, it was all those unjustly treated on the victory stand. It was a power fist for everyone,” Smith says. “I was completely surprised at the attention it got. My hope, today, is that [the gesture] sparks the improvement of conversation — that we move forward through conversation — and justification for equality across the board.”

Interviewing Lewis for the documentary, Kaino says, was the catalyst for the upcoming Mass MoCA exhibition, “In the Light of a Shadow.” The show draws on the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery march in Alabama, which Lewis led, and the 1972 Bloody Sunday killings incident in Derry, Northern Ireland. Kaino had heard stories about the latter from former Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams; Lewis relayed stories about Selma to Kaino during filming.

“I was inspired to figure out a way to connect those stories,” Kaino says. “What it meant to have these two monumental instances of public resistance against police brutality, two Bloody Sundays.”

One piece in the exhibition, still untitled, is a 26-foot-long twisted steel ship with a translucent resin skin surrounded by about 5,000 chunks of hanging asphalt — protest rocks — that Kaino sourced from around the world. They appear to be tiny ships at sea, with used postcards as sails.

Another work, “Revolutions,” is a 10-foot-tall circular “sound sculpture” made of steel pipes, conceived as a border wall wrapped around itself forming a cell. It plays the U2 protest anthem “Sunday Bloody Sunday.” A Kaino-directed music video that premiered this summer — in which his studio’s political director, Deon Jones, sings a slow and soulful version of the U2 song with Stephen Colbert’s bandleader, Jon Batiste, on piano — will be projected, intermittently, through the bars of the work. Visitors will be invited to play the pipes, COVID-permitting, when the show opens.

Kaino picks up a rubber mallet and slowly circles a study of the structure, tapping each pipe gently but intently and sending those first few familiar notes ringing throughout his studio. “Sun-day… Bloo-dy … Sun-day …”

“The entire show is about how we can create moments of progress in the face of many different seemingly conflicting crises,” Kaino says. “People think we have to choose — climate justice, social justice — it’s all one crisis. Caring is not bound to one thing.”

Eight months into a pandemic and with post-election political tensions still roiling across a country divided, “there is still room for hope,” Kaino insists. “For magic.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.