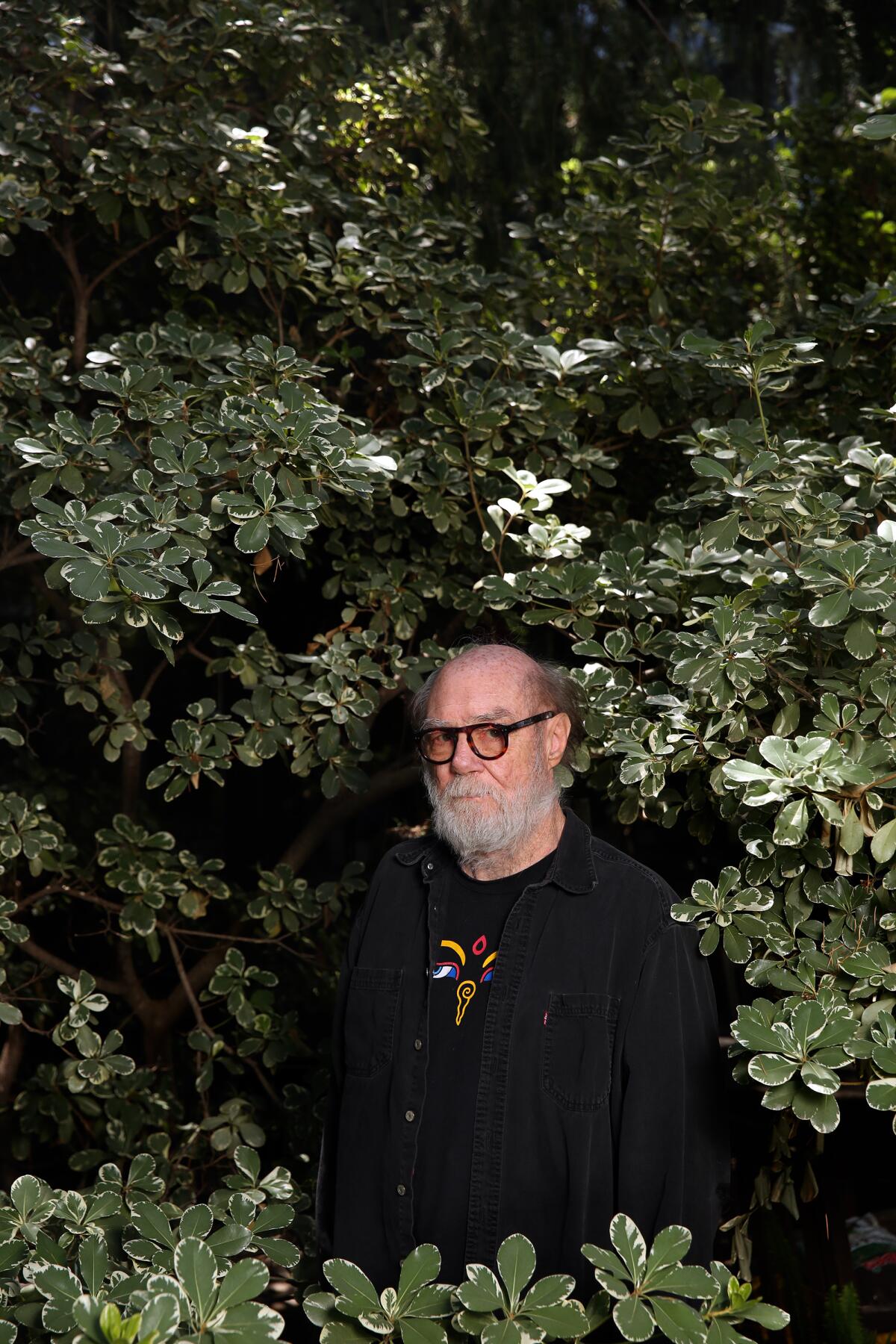

What artist Paul McCarthy has drawn and learned from Instagram in the pandemic

For half a century, artist Paul McCarthy has made work inspired by a most abject muse: the toxic male ego at its most infantile and belligerent. Sailors, pirates, cowboys, U.S. presidents from Reagan to Trump, even Walt Disney, that authoritarian inventor of antiseptic fairy tales, have materialized in various guises in his fornicating sculptures and gross-out films.

Yes, the Los Angeles artist knows how to generate a headline, such as the time in 2014 that his sculpture “Tree,” an 80-foot inflatable resembling a luminous green butt plug, was vandalized in Paris.

But girding this sensational work is an unblinking examination of our crude national id, accompanied by a lifelong drawings practice that has served as a way of tackling these ideas visually.

Over six decades, there isn’t a way in which McCarthy hasn’t employed drawing: as storyboard, as architectural schematic, as gag, as poignant visual diary, as conceptual piece, as charming doodle.

In February, the Hammer Museum gathered more than 600 of these works in the exhibition “Paul McCarthy: Head Space, Drawings 1963-2019,” co-curated by Connie Butler and Aram Moshayedi. The show captures the artist’s dexterous range.

His materials include wallpaper and bathroom stalls. His tools include his own penis and hunks of charcoal. Some of his drawings overwhelm with scale, such as the majestic “Baby World,” from 1984, which reaches an expanse of more than 21 feet and somehow makes testicles and winking anuses seem ... well, majestic.

Paul McCarthy’s drawings crawl inside your head space, making the Hammer show deft, exhausting and painfully timely.

The exhibition was shut down by the pandemic — and though it remains installed, it is unclear whether it will ever reopen. However, the show’s well-rendered catalog reproduces the works in the exhibition (even if scale and texture are lost). And the museum has placed a selection of images from the show online. Which means it’s possible to see McCarthy’s work — at least in facsimile.

Plus, on June 25, Hauser & Wirth will feature an online exhibition of drawings made right before the safer-at-home orders were issued.

Since March, the artist has been housebound in Altadena. During this time, he, like many other artists, has taken refuge in drawing. In this lightly edited conversation (which took place before cities erupted in protest over the killing of George Floyd), McCarthy talks about what he is drawing, how his high school work materializes in his museum shows and why he is intrigued by Instagram.

What were you working on when the safer-at-home orders landed?

There are these groups of drawings that are called the “A&E” drawings and the “NV Night Vater” drawings. They’re done with [Lilith Stangenberg], who is an actress in Germany. We had planned on shooting a film in August and doing a series of drawings, scheduled for the March period. We worked for about seven days, then the shutdown happened. When the studio shut down, we continued to make the drawings, but with no people around.

In the beginning of this thing, I thought we would film in August. That’s how naive I was. But with each step, you get a grip on the extreme nature of this, the horror of it.

Have you continued to work during the pandemic?

I’m working everyday, all day, but it’s not so specific to something. At home, I have a big room that I draw in. Right now, I’m drawing scenes from a script. They are not really storyboards. A storyboard will pin you down. I am using them to understand what things might look like. It’s using the script to initiate a drawing. So I do a set of these very detailed drawings. And I do drawings from books that I’m reading.

What books?

I’m reading this Norman Mailer book, the last book he wrote, [“The Castle in the Forest”]. It’s a fictional book based on the autobiography of Adolf Hitler. I’m drawing that, and I’m drawing scenes from the script that I’m writing. Those I’ve been doing for the last week or two. They are smaller and made with colored pencils, which I’d never really used before.

I just made some drawings that are the exact opposite of the very detailed ones. They are very fast and very hectic. I draw on the iPad too. I do that a lot — experiment. That’s why there is so much variation in the drawings.

The show at the Hammer begins with a self-portrait from 1963 in which you depict yourself as a monkey. It’s also the cover of the catalog. What inspired it?

That’s when when I was in high school in Utah. That monkey or chimpanzee or gorilla — I don’t remember where I got the image — I’m sure I took it from a photograph. I don’t exactly remember drawing it, but I remember giving it the title and saying, “That’s me!” I was aware of the criticality of the title [“Self-Portrait”]. Humans aren’t that far removed from animals, our conscience isn’t that far from animals.

I’ve learned a lot on Instagram — like how violent nature can be.

— Paul McCarthy

When I was in high school, I made a sculpture [of a torso] that looked like a Henry Moore. It’s about a foot tall and made of plaster. I carved it and molded it. When I was in the Whitney Biennial [in 2004], I had it computer rendered, and I had an inflatable made and I put it on top of the Whitney building. So what I did is made an inflatable of a sculpture I made in high school and used the Whitney building as a pedestal for the sculpture.

So, a work of art from high school appearing in some central way, it has happened before.

Your work is often figurative, but you made drawings in the 1960s and ’70s that were architectonic. How has your interest in architecture shaped your work?

Being an artist in the ’60s was being aware of minimalism and Frank Stella and Kenneth Noland and hard-edge painting. And you have Clement Greenberg and concreteness in art, and that minimalism is not representational.

But I’m making minimalism with reference to the body. In “Dead H,” the “H” is for human. The “Dead H” was the cross between the arms and legs. When I made the sculpture, it’s my size, but without my head. If you look into the leg, you could see down the shaft, which was hollow. It tells you that there’s a void.

They were all pieces dealing with the void — the existential void. So you had these pieces about interiors and exteriors and referencing architecture and architecture being a body.

The architecture started coming into play in performances I was doing in the 1970s. “Onion Film” and “The Fly Film” [which featured variations of a camera spinning or looping around a room] are related to architecture. Later, the performances began to merge with the architecture.

The films now, like “Night Vater,” they’re shot on a set. The set is about 100 feet long and about 40 feet wide and it has like 15 to 20 rooms and hallways and it’s this maze and in the center is the operation — the brain. The architecture begins to be occupied by the dream. It’s the container of perception.

The “Sailor’s Meat” drawings can reach a height of 17 feet. “Baby World” is 21 feet wide. How do you draw at such as massive scale?

They are performative, in a way. Those big “Sailor’s Meat” drawings, to make the lines, you have to move the whole body. I do it on hands and knees. There is no stick. Until four years ago, I always painted or drew on the ground. There were some splatter paintings I made standing up, but 99% of the paintings I’ve done were on the ground. That way you can get on top of them, especially the big ones.

When “Baby World” happened, I made 10 or 15 drawings. That’s the biggest one. I made those all about the same time in the ’80s. I kind of quit doing public performances in ’82 or ’83, and so the drawings started up again. I had been stuck in Europe with no money and, psychologically and physically, I was like, “I can’t do that anymore.”

The art world had also changed. The alternative spaces became more institutionalized in the ’80s. It became more theater-based or cabaret. So I think the combination of the art world changing and wondering what I was doing, I decided I’d go back and draw.

Plus, “Baby World” — we had kids. I did make a number of pieces about having kids and babies. [Our son] Damon is born in ’73 and by ’73, ’74 and ’75, stuffed toy animals start entering my work. I have pieces where I imitate babies. I do this piece where I put an American flag up my ass with a Pampers box on my head while [my wife] Karen is holding [our daughter] Mara. It’s all going to find its way in.

What’s the most surprising thing you turned up in putting this show together?

The “Wallpaper Drawings” [from the early 1990s, produced on wood veneer wallpaper]. At the last minute, I shipped them to L.A. — they were in Europe or somewhere. It was expensive, and I paid for it. Someone said, “Damn, that was crazy, Paul.” I said, “Why was this so expensive?” And they got here and I couldn’t believe how big they were. I thought they were much smaller.

When you moved to L.A. in the early ’70s, you wanted to draw a straight line across the city, then walk it — but you couldn’t because of all the private property and freeways. How has L.A. shaped your work?

There was a period of time where I’d say I could have made this work anywhere. I don’t think that anymore. Disneyland plays a part in my work directly. Hollywood does too.

Karen and I both chose L.A. We were in San Francisco, but the attraction to that world of ’60s and ’70s San Francisco was over. We had been part of collectives and communes and we were essentially escaping them. So coming to L.A., it was so many things. It has so many communities. It is such a huge place. So that piece, making a straight line across L.A., it’s very structural. It’s about trying to understand location.

COVID-19 has Thom Mayne, Michael Maltzan, Barbara Bestor, Rachel Allen and more Los Angeles architects rethinking design, from balconies to doorknobs.

I remember Hollywood Boulevard — I was just obsessed with the windows on Hollywood Boulevard. The store windows were these things of reflection. You could see the object in the window, but it also reflected the outside. The interior-exterior reflected beyond the glass, it spoke of what was real, but also what was not real, and this confusion of where I was.

What do you do when you’re not working? What does Paul McCarthy do for fun?

Instagram. I’m a lurker. When I was younger, I was obsessed with magazines. I would go to magazine stores all the time. I made a piece when I first got to L.A., it’s the same shape as a Carl Andre [floor installation], except I replaced all the copper plates with Life magazines and copies of the Post.

So Instagram is kind of like magazines for me. I follow 400 or 500 people, but I’m really obsessed with what it gives me. So I’ll spend a day putting my finger on flowers and the next day I’ll get a lot of flowers. I’ve learned a lot on Instagram — like how violent nature can be. I can’t do it anymore, but there’s a whole thing of animals killing animals. And then the people — men, women. It’s a whole world. You ask for entertainment, that’s entertainment.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.