In another time, not long ago, an elevator was a conveyance to reach a higher floor, an open office was a spot to clock eight hours while hoping your boss didn’t catch you checking Facebook and a doorknob was one of those banalities of architecture that seemed to warrant attention only when it needed replacing.

What a difference a virus makes.

To live through the COVID-19 pandemic is to see the surfaces of our cities rewritten by invisible narratives of contagion. Elevators now seem like intolerably small spaces to share with a stranger. The open-plan office, with its recirculated air and countless shared surfaces, feels like a flu buffet. And that humble doorknob? It could play a starring role as a protagonist named Critical Vector in an over-the-top summer movie about an outbreak.

The pandemic has changed everything about the way we live. It is bound to change architecture too.

“If you take the great architectural inventions of the 20th century: the airport, the high-rise, the freeway — those are the things that are challenged the most right now,” says Brett Steele, dean of UCLA’s School of the Arts and Architecture. “They have great density or they promise movement at high speeds. Those are exactly the things that sit at the crux of the crisis we are going through.”

“It’s a reset button for the entire world,” says Mark Lee, co-founder of the Los Angeles firm Johnston Marklee and chair of the architecture department at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. “Do we need so many new buildings? Do we need such specific programs? It raises questions that are really helpful.”

Already the pandemic has had architects and architecture schools (which spent their spring semester improvising classes and project reviews over the internet) considering the nature of buildings at a time in which one of architecture’s core purposes — creating containers that bring people together — seems almost inconceivable.

“I’m working on a synagogue, and that is a crazy problem,” says Barbara Bestor, founder of Bestor Architecture, a 25-person firm based in Silver Lake. “How do you do High Holidays after COVID with 2,000 or 3,000 people?”

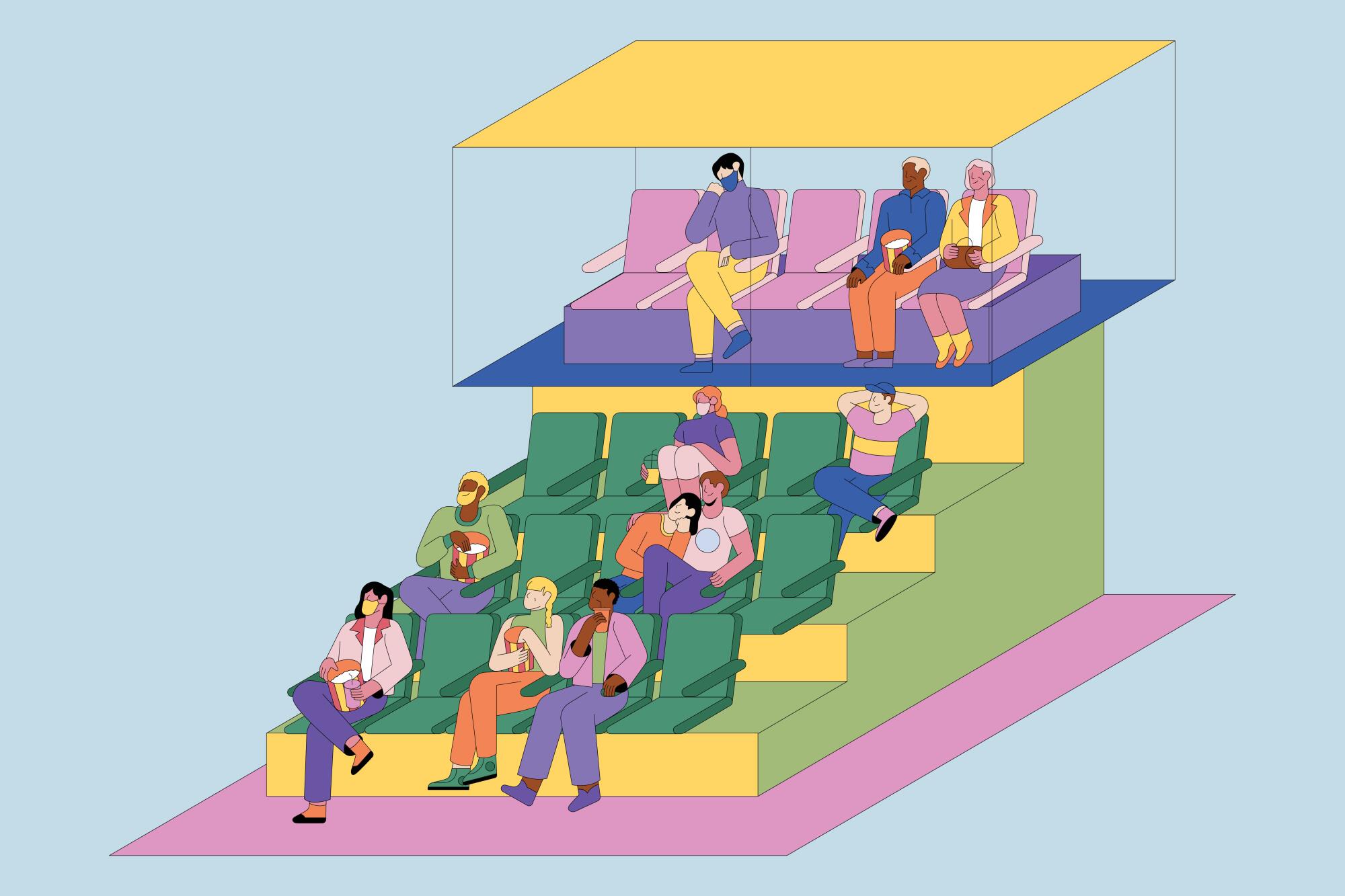

The solution may involve segmenting larger spaces and segregating the most vulnerable in a separately ventilated environment — the virus version of the glassed-in “cry rooms” contained within some churches and movie theaters. Or it may involve designing a physical space that, Bestor says, features “a robust video component so that people can watch remotely.”

It’s a reset button for the entire world. Do we need so many new buildings?

— Mark Lee, co-founder of Johnston Marklee, chair of the architecture department at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design

Gatherings via videoconference could become a way of life. Architects could find themselves designing spaces just for that purpose.

In the early 20th century, concerns about tuberculosis and sanitation helped shape Modernism — consider Richard Neutra’s influential design for the Lovell “Health House,” filled with windows and sleeping porches tailored to promote air circulation in California’s dry, sunny climate. Similarly, COVID-19 is likely to reshape the ways in which today’s architects design houses and offices, transit hubs and medical facilities. It will have architects reaching for new technologies and reintroducing old ones — say, a little less air conditioning and a lot more cross ventilation.

People do not want the executive holed up in the corner office. And cubicles are nasty.

— Barbara Bestor, founder Bestor Architecture

Weathering the storm

But first, architecture firms, like all other businesses, must weather the pandemic. Design studios have atomized, with staffs working remotely from home. And though construction on existing projects remains underway in many locations, including California, where it has been deemed essential, the design of new buildings has largely halted, threatening the economic stability of many firms.

Every month, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) reports on architectural billings for an estimated 700 U.S. firms — an index that can generally be used to project construction spending over the following nine to 12 months. From February to March, billings tumbled “dramatically” according to the April report. (An embedded graph looks like a literal cliff.) The most recent index, published in May, showed a continued plunge — “the steepest decline on record.”

Of the 12 Los Angeles firms contacted for this story — including a small seven-person shop, studios that employ dozens and the L.A. outpost of a global design office with more than 1,200 employees — 11 reported having projects suspended. For now, they are holding onto most of their employees. Only two studios reported laying off employees and two reported furloughs.

The majority of architects interviewed, however, expressed anxiety about what is to come. “We might not,” said one architect, “have any new starts in the fall.”

Kermit Baker, who serves as the AIA’s chief economist and helps produce the organization’s various economic reports, says he has seen a couple of major downturns in his 25 years at the AIA but never anything like the pandemic. “The first was the 9/11-dot-com bubble, and the other was the recession of 2008 and 2009,” he says. “There is little meaningful comparison.”

The economics are dire. And yet there is a determination to not waste the moment.

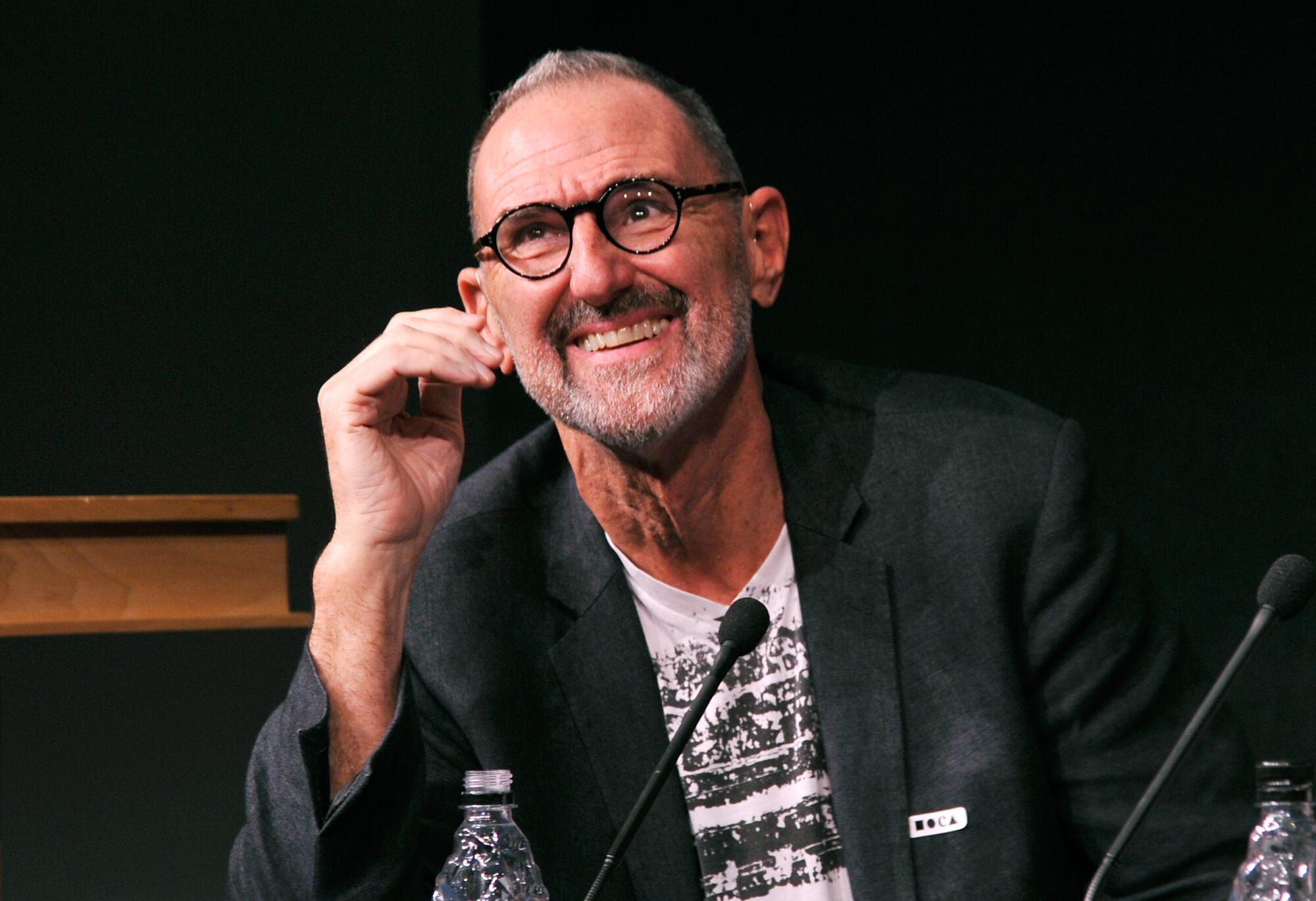

“Every crisis is an opportunity,” says Hernán Díaz Alonso, director of the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc). “The optimist in me believes that this will force us to reevaluate everything that we do.”

This is a time, he says, to ask “the big metaphysical questions” about architecture and its purpose. It’s also about considering the nuts and bolts. “If we don’t get a vaccine, what does that mean? What does that mean in terms of physical space? What do you do with a doorknob?”

Do we keep the open office?

We work in teams. ... It’s a matter of putting barriers between groups as opposed to every individual.

— Paul Danna, design partner for Skidmore Owings & Merrill

Some of those immediate questions revolve around the office.

In 2015, almost a quarter of the U.S. workforce was already doing some or all of its work from home, according to data published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In early May, Twitter announced it would make remote working a permanent option for its employees. Later in the month, Facebook announced a similar move. If others start doing the same, it will have a tectonic effect on commercial real estate markets. It also means that the office as we know it is about to be transformed.

Bob Hale is partner and creative director at L.A.-based RCH Studios, a 160-person architectural firm that has worked on office projects around the U.S. He says that some of his recent office designs called for “densities that were twice what it was 20 years ago.” COVID-19 is likely to put the brakes on that trend. “Densities of offices will change,” he says.

This raises questions about one of the most popular — and widely reviled — workplace designs: the open-plan office, in which rows of workers are jammed around long bench desks.

These are settings that have a poor track record when it comes to producing actual work. They also, according to a Danish study from 2011, account for significantly higher rates of sick leave — a phenomenon that played out in a study published by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in April, which showed the ways coronavirus hopscotched around an open-plan call center in Seoul. (Also, is it too much to want to sit at your desk and eat a sandwich without feeling like you’re on display?)

For years, design writers have penned obituaries for the open office. And some are certain coronavirus will put another nail in the open-plan coffin. But Lawrence Scarpa, a founder of Brooks + Scarpa, a 22-person firm with offices in L.A. and Fort Lauderdale, says “the open office is not going away.”

For one, real estate in cities like L.A. is too valuable. Moreover, office culture is increasingly casual, and therefore architecture is unlikely to go back to the formal, private dens of “Mad Men.”

“It satisfies a younger generation who wants a spatial equality in the office space,” says Bestor. “People do not want the executive holed up in the corner office.”

That said, Bestor does not see a triumphant return for the cubicle, which at least gave the illusion of privacy. “Cubicles are nasty,” she declares.

Instead, many of the architects I spoke with visualize once-cavernous spaces segmented into more intimately scaled settings with small clusters of desks. “We work in teams, so it’s easy to think of people in groups,” says Paul Danna, a design partner in the L.A. office of Skidmore Owings & Merrill, a global firm at work on an office development in Pasadena. “It’s a matter of putting barriers between groups as opposed to every individual.”

Ultimately, most architects said the office of the future will likely be less focused on desks and more on meeting and gathering spaces.

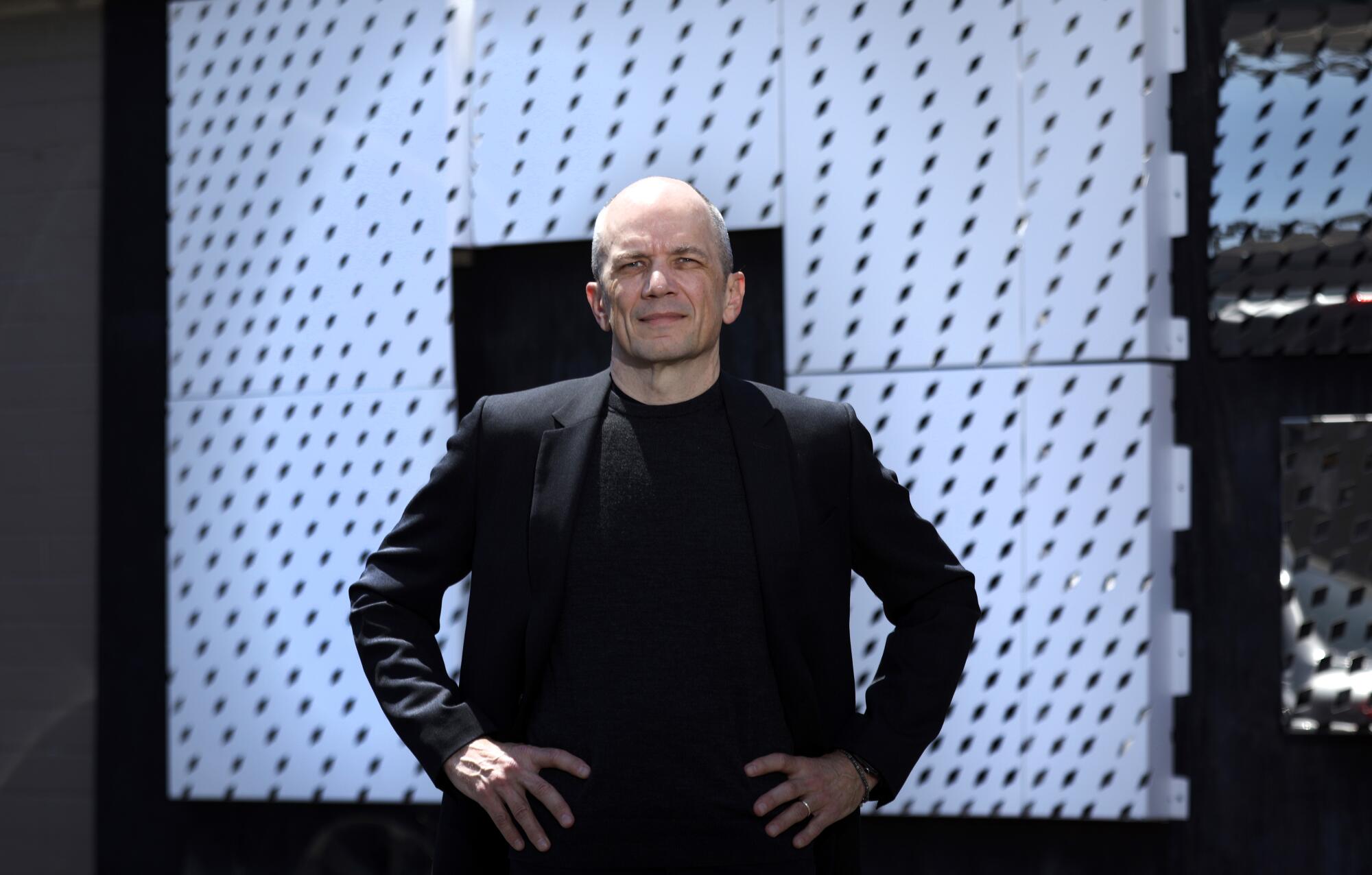

It’s a future that some designers are already envisioning for their own firms. “I’m meeting with my associates and we are planning a radical shift in how we work,” says Thom Mayne, the Pritzker Prize-winning architect who founded Morphosis, the 90-person studio that designed the CalTrans District 7 headquarters in downtown L.A.

He says the pandemic has been a great test of remote working for his office, one that has offered a bevy upsides: more flexible work schedules, hours gained by not sitting in soul-crushing traffic and the improved air quality that comes with less car commuting.

“I am moving two-thirds of the desks out of the office and it will be more of a meeting place,” he says of his Culver City office. “We need couches and tables and comfortable chairs instead of just desks. It redefines the idea of everybody has a desk.”

I’m meeting with my associates and we are planning a radical shift in how we work.

— Thom Mayne, architect

In fact, the office of the future may look like the office of the 1990s: Scarpa says that once fears of transmission have passed, we may see a return to “hot desking” — a “flexible,” “more space-efficient” environment in which “people no longer have their own desks but a shared rotating desk” — and plenty of sanitized wipes, we assume.

Home and the air that we breathe

Balconies should be a human right. Shade and balconies.

— Barbara Bestor, founder Bestor Architecture

Change is also coming to the home. Certainly, the coronavirus has made glaringly evident L.A.’s shortcomings in the areas of housing construction and design. Single families in single-family homes have been waiting out the governor’s safer-at-home orders in relative comfort; others, not so much. The pandemic, says Mayne, “makes extremely clear the importance of urban housing at multiple economic types. That is the biggest urban problem in Los Angeles.”

Nearly 60,000 people in L.A. County are without permanent shelter — a figure that is unconscionable on an ordinary day but at the moment represents a public health tinder box. Countless other Angelenos have been crowded into small apartments with little access to fresh air.

“I have one employee who lives in an apartment without any outdoor space,” says Rachel Allen, founder of RADAR, a 10-person firm with offices in Chinatown. “She’s the one going the most crazy. She hangs out in her parking lot.”

Nursing homes are going to be very unpopular for a long time. More folks than ever are going to want Grandma in the backyard where they can keep eye on her.

— Rachel Allen, founder RADAR

For starters, L.A. needs to build more housing, faster and more efficiently. The design solutions for that may already be at hand.

Prefab construction, in which a building’s key components are manufactured in a factory and then assembled on site, is already going mainstream in places like Japan, Germany and Sweden. In Los Angeles, Michael Maltzan Architecture used prefab techniques in its design of the Star Apartments for the Skid Row Housing Trust in 2014. Now Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects (LOHA), is doing the same for a 54-unit project for Clifford Beers Housing that is under construction in South L.A.

Isla Intersections, designed to serve formerly homeless individuals and families, is being crafted from custom-built shipping containers. If it had been constructed as a regular apartment complex, the development would have taken four years to complete. By employing prefab, it will take two. Says the firm’s founder, Lorcan O’Herlihy: “Speed is the essential issue.”

It’s a method that can be applied to other housing types as well. LOHA is also at work on a pair of modular homes crafted from wood. “We think,” he says, “this will really be of interest.”

But to use these time-saving methods with more regularity, the city’s Department of Building and Safety will need to be more open-minded about permitting prefab designs.

“It’s still challenging,” says O’Herlihy, of contending with the red-tape. “The city is better at it now, but they are still apprehensive about it.”

The pandemic, likewise, has put a spotlight on the need for residential design that is more humane — especially when it comes to multifamily units and apartment buildings. “Balconies should be a human right,” says Bestor. “Shade and balconies.”

Cross-ventilation, roof decks, balconies, courtyards, gardens and other outdoor spaces have been considered luxury amenities. O’Herlihy, who has long applied these principles to his work, even in his affordable housing designs, says the pandemic could make them essentials.

“There is an opportunity to give more gravitas to our clients about passive design, about greening up buildings,” he says. “One can imagine that all of those aspects will now be taken far more seriously.”

With all of this, the shape of the home as we know it is also liable to change.

Speed is the essential issue.

— Lorcan O’Herlihy, founder Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects

For one, the average middle-class home will likely include a home office as a standard feature. It will mean adjusting homes in other ways too.

Already, over the last decade, the so-called Boomerang Generation — adults in their late 20s and early 30s — have increasingly returned home to live with their parents. For architects, this has meant thinking about designing multigenerational homes that serve children when they are small but also as adults. Now the pandemic has added work-from-home to the mix, creating a scenario in which multiple adults may be working in a home at one time.

Home design may, as a result, shift to incorporate larger bedroom spaces that children can inhabit over time and also use as a remote workspace. “Something like a loft within a family home,” says Allen.

And every home may need a corner or two that functions as a ready-made Zoom backdrop (or risk having your decor deconstructed on Twitter). “There is this intersection with built and virtual space,” says Díaz Alonso. “That will be a factor moving forward.”

Smart density

In late April, urbanist Joel Kotkin wrote an op-ed for The Times in which he noted that L.A.’s “dispersed urban pattern has proven a major asset” in the midst of the pandemic, noting that infection rates were below that of denser cities like New York. It’s probably wildly premature to be doing any end-zone dances in favor of sprawl, given that the pandemic has yet to fully play out. And, as Scarpa notes, sprawl, with its traffic and attendant accidents and pollution, “is killing us — slowly.”

In fact, almost every architect I interviewed for this story says that it remains essential for L.A. to move forward on increasing density. But, says Milton Curry, dean of the school of architecture at USC. “We need to do it smartly.”

Currently, the model for density in L.A. consists of podium apartments: two stories of concrete parking structure, topped by several stories of apartments. Or as Bestor likes to describe it: “Parking, followed by three stories of crap.” Outdoor space may consist of a few decorative hedges at the perimeters. Only the most high-end ones feature courtyards or roof decks.

Bestor says the pandemic has revealed the urgency for better models.

In a development that occupies a whole block, for example, parking could be relegated to one corner, apart from the residential structures, she says. “You put the parking in one corner and then you walk to your apartment through an open space.” From there, you have groupings of three- and five-story buildings with their own entrances. “That’s a good form of density for L.A.” she says, “and it’s easier to manage COVID situations because it’s not one lobby for a million people.”

Ideally, urban planners would then find ways to incentivize the connection of green spaces so that these outdoor areas aren’t happy accidents but a continuous green lung.

“This is the moment to push for pocket parks and other things that allow us to exist together in a dense environment,” says Sharon Johnston, cofounder of Johnston Marklee. (It’s a strategy her firm deployed in its renovation and expansion of UCLA’s graduate art studios, which has a courtyard and open-air work areas.)

In the interim, the efficient use and reuse of our existing infrastructure will be critical. If fewer buildings are used as commercial office space (which looks highly likely), that could make way for those buildings to be turned into housing. “We are already seeing some office-to-housing conversions in Koreatown,” says Allen.

And in January, California relaxed rules for constructing ADUs — accessory dwelling units, or granny flats — which continue to bring smart density to the city. “Nursing homes are going to be very unpopular for a long time,” adds Allen, whose firm has worked on many of these. “More folks than ever are going to want Grandma in the backyard where they can keep eye on her.”

But many of these shifts will depend not just on architects but on city planning.

Michael Maltzan, whose 25-person firm has worked on a range of civic-minded projects, including various supportive housing projects and the design of the Sixth Street Bridge (which has remained under construction during the pandemic), says now is the time for the city’s various design and planning branches to convene working groups.

“They need to get feedback from a wide group of people who are involved in medicine, in resources, in mobility, in architecture, to talk through these issues and begin to set out guidelines and ambitions for buildings,” he says. “One of the things I’m focused on is how we can continue to maintain the increase in density, especially in housing, to help with the affordability problem — which is not going to get better.”

Cities have evolved in relationship to past crises and pandemics.

— Michael Maltzan, founder Michael Maltzan Architecture

The critical piece of this puzzle will be for government to include architects in the planning process rather than bringing them in after the fact.

“We have too long ceded decisions of development to the financial community,” says Curry. “There needs to be more pressure on government to do things that are in the interest of the city.”

The role of technology

)

Health benefits will have to be weighed against privacy issues.

— Paul Murdoch, founder Paul Murdoch Architects

One challenge facing architects and engineers in the coming months will be to figure out how we might safely co-exist in buildings that bring a wide spectrum of people together: community centers, medical buildings, office towers, classrooms, airports and train stations ... the list is long.

Initially, it will likely be the more mundane technologies that receive scrutiny, such as heating and ventilation systems. Danna at SOM, at work on a design proposal for a trio of high-rise towers in downtown L.A., says that in the short-term, concerns over COVID-19 will mean more frequent filter changes and a greater proportion of fresh versus recirculated air in ventilation systems.

But the pandemic could bring a literal top-to-bottom change to how ventilation systems are designed.

Typically, air is brought through ceiling ducts and blown down into a room, then extracted back into the ceiling — creating a circular pattern. But some buildings now feature underfloor air systems that bring in air from below at a lower velocity. As the air warms it rises naturally to the ceiling, where it is extracted.

“It’s more efficient,” Danna explains. “You don’t have to have equipment that is working so hard ... you have to expend a lot of energy to blow it down.” It also means that potential contaminants aren’t so easily circulated around a sealed room.

The pandemic will likely hasten the deployment of existing technology: hands-free systems such as automatic doors and cellphone payment systems.

“One of the projects we are working on right now is e-gates for the Tom Bradley Terminal,” says Paul Murdoch, of Paul Murdoch Architects, a seven-person firm that has designed highly trafficked public spaces such as libraries, as well as administrative and other facilities for LAX. “It’s an electronic gate. It uses facial recognition. There are no boarding passes to exchange. There is nothing physical.”

He also envisions spaces such as airports developing health screening protocols that require flexible forms of architecture that can adapt to conditions.

“There may be certain thresholds that are created physically” — say, a set of sliding glass doors — “and at those thresholds you get your temperature scanned,” he says. “Those could be modulated depending on the level of danger. If there is a high threat level, you set up that threshold as an airlock or a set of doors. If the threat level is low, it can be left open.”

Kulapat Yantrasast, founder and creative director of the L.A.-based firm wHY, has been working on putting together a working group of arts leaders, architects and engineers to produce a white paper on how museums might safely reopen. (Among various other cultural projects, Yantrasast’s firm is working on interior design for the new Academy Museum of Motion Pictures.) “Before capacity was calculated by fire safety,” he says. “Now capacity will be recalculated with distance in mind.”

He says he’s been looking into rising technologies such as nanocoatings, molecular sealants that could be placed on high-traffic surfaces — such as banisters and doorknobs — to prevent the accumulation of contaminants. Currently, these are used in anti-graffiti coating, which prevent paint from adhering to a surface. But their medical use is still in development.

Before capacity was calculated by fire safety. Now capacity will be recalculated with distance in mind.

— Kulapat Yantrasast, founder and creative director of wHY

He and other architects interviewed are also studying the use of other technologies: UV light for disinfecting highly trafficked environments, smartphone apps that can trace transmission and infrared monitoring systems that can visually distinguish people with fevers.

But, says Murdoch, in some of those latter cases, “Health benefits will have to be weighed against privacy issues.”

Old technologies too

Lee, of Johnston Marklee, cautions against getting too caught up in all the new tech. As the pandemic ravages the economy, it may be the simple solutions that are the most functional.

“It’s a good time to look at ancient ways of dealing with passive solar and air,” he says. “We don’t always need the latest technology to help us.”

The key, says Johnston, will be to design buildings that can be easily adapted to unforeseen uses. “We think of architecture as a frame,” she says. “We think of it as a place where there can be multiple uses over time — so, straddling the line between creating a specific type of environment and allowing other things to take place in it.”

This is the moment to push for pocket parks and other things that allow us to exist together in a dense environment.

— Sharon Johnston, co-founder Johnston Marklee

In other words, a home that can function as an office. An office that feels a bit like a lounge. An airport that can screen for health. A convention center that can be turned into field hospital.

“Cities have evolved in relationship to past crises and pandemics,” Maltzan says. “I expect that the form of our cities will continue to do so.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.