The afternoon I heard that Los Angeles was shutting down to fight the deadly new coronavirus, I did what my gut always tells me to do in times of crisis. I headed straight to the beach.

Whenever stuff is rough, whenever a reset is needed, the ocean is a salve. I’m not a boat owner, an ocean sports enthusiast or even a surfer. But I am a native coastal Southern Californian. Thus, two things were immediately clear in my mind.

First, we had to join together to fight back the COVID-19 respiratory disease. And second, we could not allow ourselves to lose our spirit as people of this land. I had to run to the beach.

In childhood, my mother would tell us as explicitly as she could that SoCal beaches were “ours,” all of them. It didn’t matter that other people had boogie boards and lavish barbecues, while all we could afford for picnics at the time were a few plastic tubs full of quartered oranges doused in chile salt. We were from the barrio but enjoyed the beach just the same as the wealthy around us. The beach was an equalizer.

Luckily today, I live close enough to the beach to make it an easy, spur-of-the-moment drive, the same as other Angelenos who maintain intimate relationships with their respective hills or canyons farther inland, or those who find their escapes in shopping malls or urban parks. I watch and listen to the waves, inhale the salty air, read a bit, or not, and then leave. This is how I find solace at the sand.

On March 12, the day after the World Health Organization first called the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic and the NBA suspended its season, when a flurry of entertainment events were postponed or canceled, and cultural institutions all over began shutting down, I spent a prudent and necessary half-hour at the quietest beach I know in L.A. city limits, Playa del Rey, to watch the sunset.

Bikers, joggers, couples sped along the walk in the chill of the waning light. A pink and crimson sunset gave way to purple over the rocky edges of the marina. I really needed the air and the sight of other Angelenos sharing the collective emotions of grief and fear as the ramifications of the looming crisis were becoming clear.

Would California be able to “flatten the curve” successfully while not losing its soul? Our silent glances seemed to carry the question into the air.

Every day since, I’ve gone outside, usually to the water or to a park near home. I haven’t been alone. And that’s a problem in these coronavirus days. From Echo Park Lake to Malibu, from the craggy south-facing cliffs of San Pedro to the creeks of the San Gabriel foothills, L.A. residents say they have found reassurance and rejuvenation in the open air, even as officials seek to clamp down even further on our use of public space.

On Monday, Laguna Beach announced a closure of its beaches and trails, citing too many visitors “from inland cities” overwhelming the city’s ability to ensure social distancing outdoors. The move followed closures of parking lots at Santa Monica and Venice beaches. Upping the ante, Gov. Gavin Newsom later ordered the locking-up of parking lots at state parks, a “soft closure” delivered like a stern parent’s warning. The same day, L.A. County said it was closing all unincorporated trails, which felt like another punishment.

I had one response to these developments: Gulp. I followed this with another quick in-and-out trip to the shore.

One of the last channels of social cohesion and mental well-being that we have left as societies fight the global pandemic is access to public lands, and the public right-of-way. Access to the sea. Especially here.

Being outside is how we make life happen as Southern Californians. It is a sensation that unites all, from folks who pine from a cramped stucco apartment balcony to those who bask in the luxury of a backyard with citrus trees. Our instincts take us to fresher air, in good and in ill. Our obsessions with gardens, plants and trails are hopelessly intertwined with the grace of the region’s fine weather. We are bound, at a mountain called Disappointment, or along a concrete river that once spewed as it pleased, untamed, across the floor of the L.A. Basin.

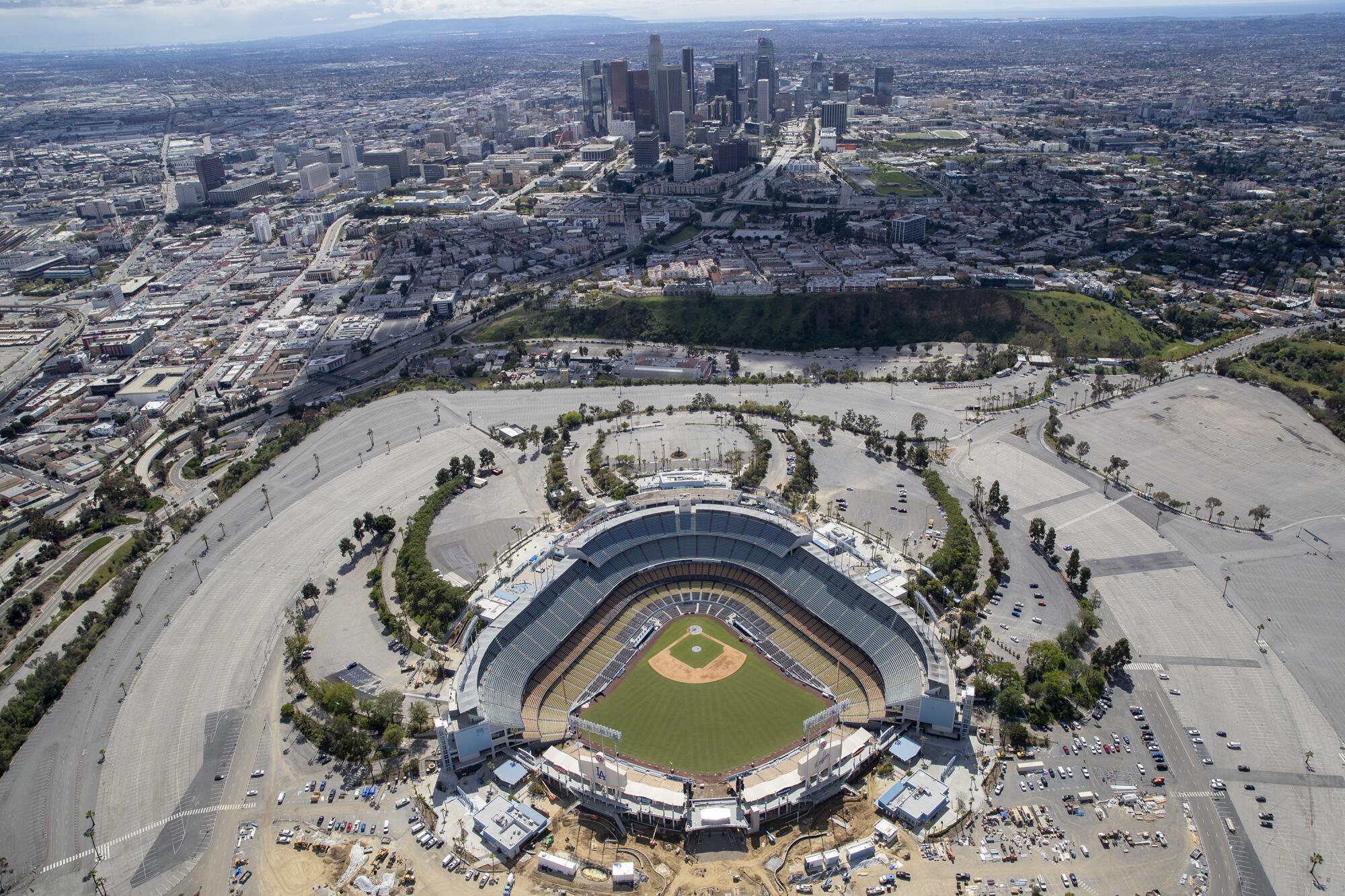

As I did that first day, and since, I’ve spent many hours alone fretting over the threat of COVID-19, and mourning the loss of life. I’ve also spent time fretting over the threat that local officials may soon attempt to forbid us from going outside at all — as Italy and Greece have done, to help fight the virus. In the meantime, Angelenos are largely heeding the instructions: Big, wide places where we’ve always seen humans interacting — malls, piers, even the freeways and overpasses, designed as spaces where we can move — are now devoid of people, on pause, without purpose.

Access for all

Christopher Hawthorne, chief design officer for the city of Los Angeles and the former architecture critic for this news outlet, said in an interview that he and city officials up and down the City Hall ranks were aware of the needs of regular Angelenos to enjoy their parkland and coastline. The crisis is forcing all of us to make sacrifices, he said.

“It’s really a matter of common sense,” Hawthorne said on Monday. “There’s a lot of space to operate, but people have tended to concentrate in popular spots. It’s certainly not the case that the entire city is crowded. There are plenty of places to go.”

Indeed, Los Angeles has more than 450 parks at our disposal, said Parks and Recreation spokeswoman Rose Watson. Indoor facilities such as city recreation centers and museums are closed — and on Thursday, outdoor sports facilities (skate parks, tennis courts, baseball fields, basketball courts) were closed. But the land and grassy plains that surround them currently remain free for all those not in a hard virus-related quarantine if we can keep 6 feet away from others.

Yet recent displays of overcrowded trails at Runyon Canyon and Griffith Park, Hawthorne noted, are cause for concern.

“We’re asking everyone to think of the city and the region as a whole. This is about keeping that common good in mind,” Hawthorne said. “We’ve seen scenes of crowded public spaces all over the country, but my own sense is that people here in Los Angeles on the whole are being very careful and respectful, and we appreciate that.”

Mayor Eric Garcetti seemed to bolster the necessity for fresh air and safe socializing in statements he made March 20 as he described what he saw on walks in his neighborhood. “Suddenly, our big city feels like a small town,” Garcetti said during a briefing.

“People literally were waving, singing, shouting nice things — at a safe distance, of course — interacting with each other,” Garcetti went on. “It was wonderful to see the spirit of the city, and its hope on the streets, the goodness of its people, in each one of these interactions.”

He dubbed the general vibe of the moment as “L.A. Love.” Solidarity with others during the crisis must guide our personal choices, he argued. Stopping the spread of the coronavirus is the top priority.

“Right now, this is about socially coming together, even as we physically distance from one another,” the mayor said. “And here’s just a parent hack: You can do P.E. and instruction at the same time, if you walk and talk.”

By Sunday, Garcetti had adjusted his message. The mayor warned of more closures if L.A. residents did not adhere to the guidelines. “Too many people, too close together, too often.” By Wednesday, Garcetti announced the closure of Runyon Canyon, Bronson Canyon and the Venice Pier. On Thursday, the U.S. Forest Service closed campgrounds, picnic areas and other recreation sites in forests throughout California. And on Friday came the final blow when Supervisor Janice Hahn announced that all L.A. County beaches would temporarily close.

Reasonable distance

On a recent afternoon with his family at the Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area, Larry Briggs, 42, a nursing assistant at an L.A. hospital, said he understood the need for physical distancing. But, he added, “people are going to be out here, no matter what.”

“Just making sure to keep a safe distance from others,” said his partner, Lori Brown, 50, who also works in a hospital.

Briggs and Brown and their two children ambled around the Martin Luther King Jr. memorial obelisk, set on a ridge with a commanding view of the downtown Los Angeles skyline. The setting was spectacular. “We’re just trying to be outside,” Briggs said, “while we still can.”

The implication was clear. After President Trump on Tuesday suggested the country could reopen in time for Easter, Garcetti pushed back, saying that Angelenos should be “prepared for a couple months like this.” But are we really?

Steven W. Thrasher, a journalism professor at Northwestern University, studies HIV/AIDS as well as prisons. Home isolation in a public health crisis is a meager “taste” of the “torture” that many incarcerated people endure on a far steeper scale, he said. Balancing the needs to retain physical distance from others should force a discussion of associated risks amid a pandemic, such as the threats to mental health, and for survivors of domestic abuse.

“I’m not saying social distancing isn’t helpful; it is, and it’s something that we have to do right now,” Thrasher said Wednesday. “But it comes with risk and sacrifice, and those risks and sacrifices need to be distributed correctly and rewarded.”

If the restrictions are lifted too soon and COVID-19 cases spike, he said, it could render the sacrifices of the last weeks moot.

Leticia Servin, a teacher in Long Beach, says she has been doing everything in her power to comply with the “Safer at Home” orders. Servin is leading online learning, taking yoga sessions via YouTube and practicing proper social distancing. She’s also been following an aspect of the crisis orders that she considers essential to survive it: taking walks for fresh air and exercise.

Servin, 50, has lived in Long Beach most of her life. It wasn’t until the shutdown that she began learning about green space in her general geographical sphere that she simply didn’t know about before. One such space is Signal Hill Park, at the top of the city of Signal Hill, featuring breathtaking views of the L.A. and Long Beach harbors.

“It’s been years and I didn’t realize [the park] was, like, five minutes from my apartment, and I feel like I’m kind of savvy with public places,” Servin said. “And obviously I’m not. But it’s been great, because I’ve been discovering Long Beach in a new way.”

It helps — or hinders — that spring began March 19, ensuring that bouts of fresh rain and the corresponding flower bloom that follows may draw people outdoors even more than before. But, she reasoned, what else are people going to do?

“I am going stir-crazy, it’s true,” said Servin, whose walks offer moments of tranquility and renewal in days troubled by anxiety and dread. “For your mental health, it’s not OK. It’s also causing a rift, because people when they panic do horrible things, and that’s when you see how people truly are. It’s not ‘Kumbaya,’ because we’re still in the we-don’t-know phase.”

Immunity booster

The Santa Monica Pier, one of the most famous in America, with its 1941 Streamline Moderne neon sign, concessions and vintage amusements rides is currently closed. On Sunday, Santa Monica officials also decided to close the large beach-front parking lots that feed visitors to the historical landmark. A few blocks away, the Third Street Promenade was deserted. As rain moved into the region, Santa Monica police cruisers used loudspeakers to urge rambunctious groups of young people congregating on street corners to “keep 6 feet apart.”

Nick Muller, 30, and Camille Gomez, 22, strolled hand-in-hand along the Santa Monica walkways in a light drizzle. “When I heard they were thinking of shutting everything down, we just had to come down here, and thought since it started raining, there would be less people,” Muller said. “We just want to enjoy it while we still can.”

Not long after leaving Muller and Gomez, I got a call from Denise Resendez, an educator and resident of Marina del Rey who has been a casual contact of mine since we found ourselves cavorting in Venice Beach with mutual friends last fall, in far happier and freer times.

“I can’t, I can’t, I can’t,” she said with a wail. “They’re, like, filming people out hiking right now, and shaming them.”

She was angry and unsettled by the quarantine scolding she was seeing on the news, not just against the crowds of spring breakers on Florida beaches, but also against small groups of people outdoors accused of being irresponsible or defiant of public-health orders. Who is to know if they are not families who are already in close quarters at home?

We decided to meet — outdoors, at a distance — by the ocean. It was before the beach ban was announced and she’d been in self-quarantine for days, fielding mounting calls from harried parents of her primary-school-age students. She needed air.

The rain didn’t hinder our determination. We ordered tacos and caldo to-go from Teddy’s Red Tacos on Winward Avenue and headed in the quiet drizzle to the basketball courts nearby to sit down and eat.

There, a dude dribbled and shot jumpers alone. We minded one another but didn’t share words. Behind us, two bleached-blond guys wearing half of their wetsuits, barefoot and barechested to the rain, carried surfboards toward the water.

“That’s what I’m talking about,” Resendez yelled at them with laughter. “Boost your immunity.” The surfers responded with affirmative shouts and thumbs-up.

Just then, a woman who called herself Sam pushed a grubby cart toward us and asked if we wanted any “refreshments.” Huh? we asked. Beers were three dollars and shots of whiskey were five.

My jaw dropped. I had never seen something like this in Venice, or really anywhere in L.A. Sam was under economic stress and said she had to make a living. Times are tough. Resendez and I could not stop smiling.

“See this right here? This boosts my immunity; this is part of my health,” she said from a safe 6-foot distance. “This is my Vitamin C — community.”

More to Read

Updates

1:40 p.m. March 27, 2020: This story was updated to reflect the announcement on Friday that all L.A. County beaches would be closed temporarily due to coronavirus concerns.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.