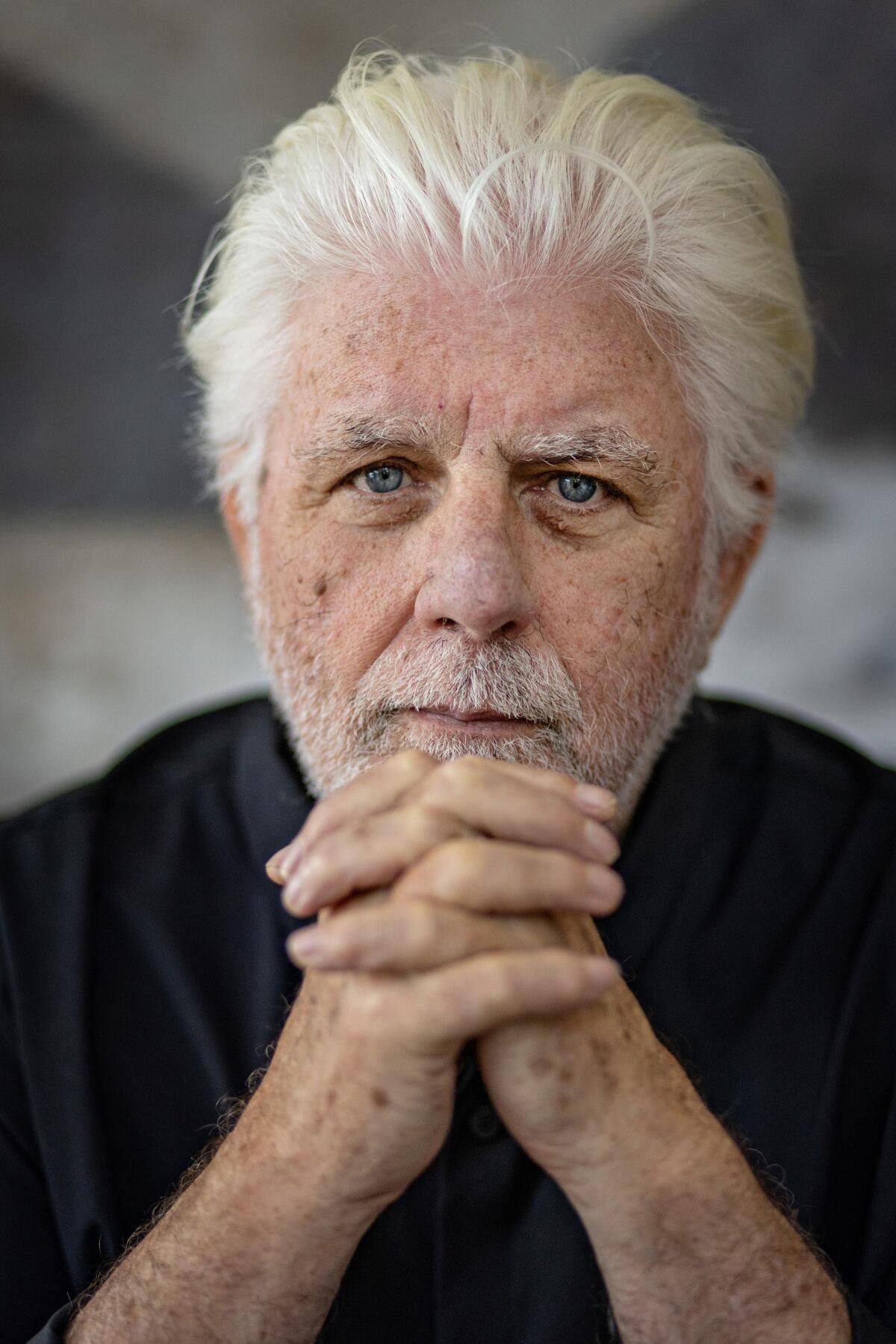

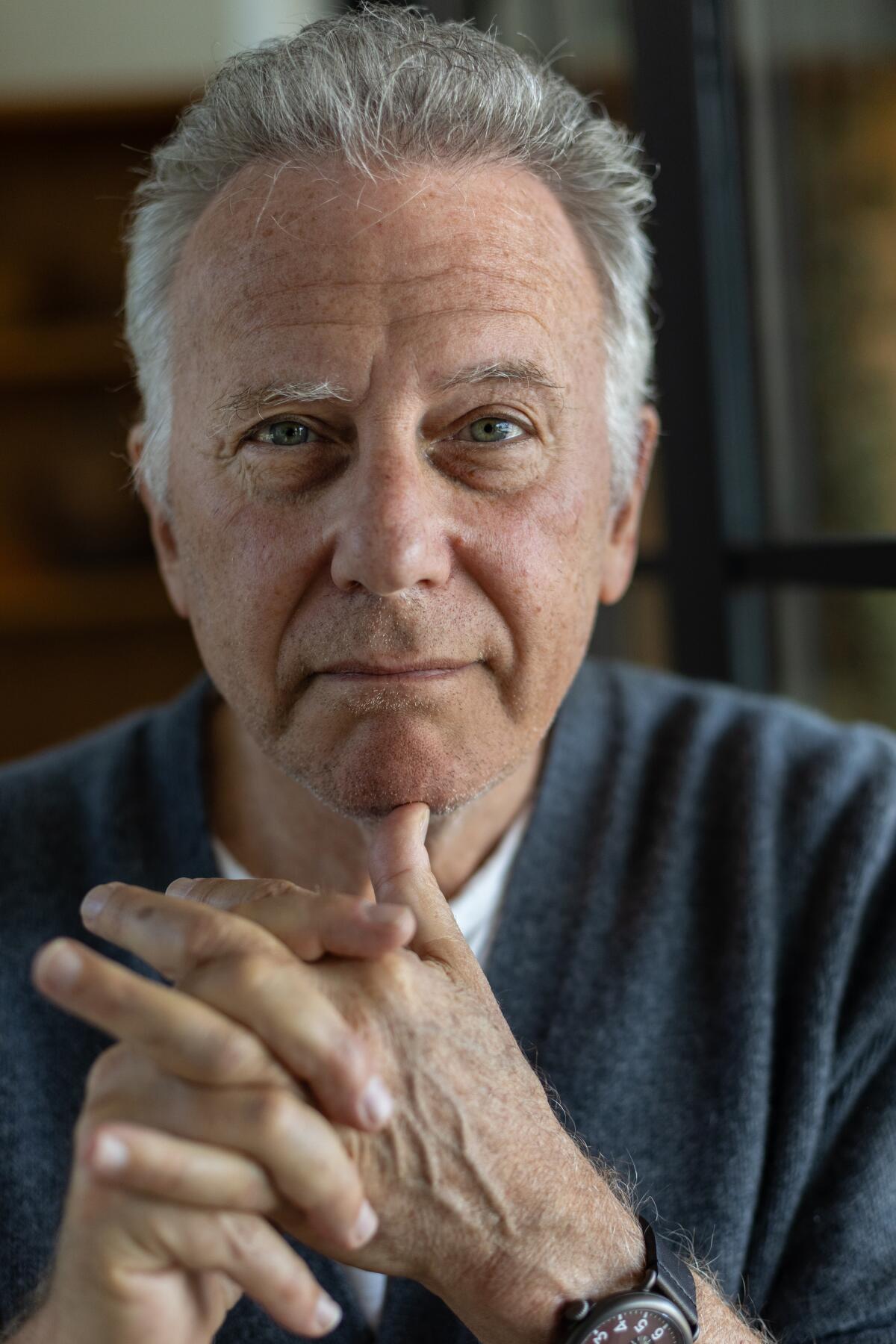

Michael McDonald and Paul Reiser on the importance of forgiveness and the problem with gossip

Michael McDonald and Paul Reiser — yes, the golden-piped white-soul singer, and yes, the veteran sitcom star and comedian — were at Reiser’s spread in Malibu the other day when something far more important than their new joint project came up.

“Forgive me, but I need to take a quick timeout,” Reiser said, calling up a menu on his phone. “Half of every writers’ room is: What are we doing for lunch?”

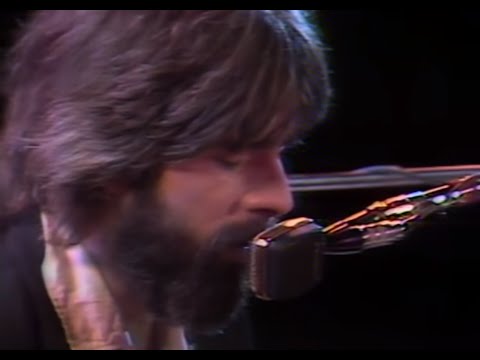

The two had earned the interruption: McDonald, 72, and Reiser, 68, teamed up to write McDonald’s memoir, “What a Fool Believes,” after they met at a party a few years ago and went back to Reiser’s to jam on side-by-side pianos. The book is titled after McDonald’s chart-topping 1978 hit with the Doobie Brothers; it covers his childhood in St. Louis and his eventual move to Los Angeles, his stints in Steely Dan and the Doobies, his eventual solo career and his struggles with drugs and booze. Reiser, whose previous books include “Couplehood” and “Babyhood,” said he volunteered for the job because he’d always been a fan but didn’t understand the arc of McDonald’s career.

“This way I could just ask him,” he added with a laugh.

On Wednesday night the two will appear together in a conversation at the El Rey Theatre; McDonald then will spend the summer on the road with the Doobie Brothers, including a June 23 stop at Inglewood’s Kia Forum. These days the singer lives with his wife, singer Amy Holland, in Santa Barbara — where, speaking of lunch, his all-time favorite Mexican restaurant recently shuttered.

“The old couple who ran it,” McDonald was sad to report, “they literally died in the place.”

Are you guys afraid of dying?

Paul Reiser: Only onstage. I’ve had some tough crowds.

Michael McDonald: I don’t know that I’m afraid of it. I let myself think about it once in a while.

Reiser: You’re not really gonna lead with this.

Hey, Mike brought up the subject.

Reiser: I’m gonna jump in front of you here.

Touring with Michael McDonald for the first time since the ‘90s, the Doobie Brothers are riding a vibe shift, driven by yacht-rock nostalgia and a Rock Hall induction.

All right, all right. The jam session that sparked this book — what were you guys playing?

McDonald: We were sitting at a couple pianos, like Ferrante & Teicher, playing Beatles songs, kind of analyzing our favorite bridges, which were so great, especially in that period of time we both love.

Reiser: Pre-“Rubber Soul.” We played some Motown too. I tried to slip in a couple of Michael McDonald songs: “While I have you here, is that an A-flat you’re playing there?”

Just two famous guys talking about chords.

Reiser: When you’re drawn to something, your brain goes there. I can’t help it —I’m watching a movie and I’m going, “How did they shoot that?” With the Beatles, it really is staggering — just this perfect 2-minute-and-39-second piece of work. I watched “Get Back,” and it was thrilling to get to see these songs as they’re forming.

McDonald: It kind of gives you hope as a writer because you realize there were moments when they had no f—ing idea how this was gonna work out.

The book grew out of a series of Zoom conversations between the two of you, right?

Reiser: That’s all it was. This was four years ago, March 2020, and I was asking Mike to explain to me this or that. I jokingly said, “You should write a book,” and he said, “Well, I’ve thought about it, but I don’t know how to do that.” I said, “I’ve written a couple — plus, we’ve got nothing else to do.” That was really a factor — that it’d be good during the pandemic to have something to wake up and do. So we both learned Zoom that week, and for about a month and a half, we’d just talk three or four days a week.

McDonald: My biggest fear was: How much of a story is this? I mean, nobody dies, nobody goes to prison.

The book does open with you in the drunk tank in Van Nuys.

McDonald: There weren’t many guys in that cell who showed up because they fell asleep in a booth at Du-par’s.

How would you rate your recall of long-ago events?

McDonald: Well, I thought if I wait another five years, I’m not gonna remember half this stuff. Lot of things I didn’t remember correctly — dates and places and times.

Reiser: He’s talking and I’m Googling: “Uh, Mike, that record came out four years earlier.”

The book has some nice writerly moments. There’s a part where you’re talking about the Doobie Brothers’ Grammy wins for “What a Fool Believes,” and you say that after the ceremony you couldn’t bear to face “the ominous quiet of my house in the hills.” Who wrote that?

Reiser: It’s all Mike. I put the conversations in a rough sequence and then he’d take it and write it so it didn’t just sound like chitchat. Sometimes he’d write it so well I’d be like, “We can’t have 47 essays.” So we’d tighten it.

McDonald: Paul was great at saying, “Here’s the story. All this other stuff, you’re kind of wasting the reader’s time.”

That’s the challenge, though, right? As a reader, I want the story but I also want the texture.

McDonald: That line you mentioned — that was a true thing for me. Going home that night was ominous because I didn’t like being alone at that point in my life. My demons were such that I usually found something to occupy myself with. I’d go out to clubs by myself just to get out of my own house.

Reiser: Now your goal is not to go out of your house.

McDonald: That’s exactly right.

“What a Fool Believes” was probably inevitable as the book’s title.

Reiser: I had to twist his arm a little bit.

McDonald: It just seemed too obvious to me. I wanted it to be something more offbeat — like, “Shut the F— Up, Teresa.”

Reiser: My sense was that you didn’t want to hang your whole life on a song title, which I understood. But there’s so many books out there. You want somebody to go, “Oh, that’s about Michael McDonald — I got to read that.”

McDonald: Now it seems like the perfect title.

Reiser: My next one’s gonna be “Does This Look Infected?”

A sunny if slightly wistful new documentary about the Beach Boys charts the band’s six decades of complicated harmony.

You write in the book about how you’d hoped to make your second solo album with Quincy Jones, but it didn’t work out: You had to move faster than he was able to, which you let a record exec tell him instead of doing it yourself. I was struck by how little resentment you seem to harbor about that.

McDonald: I think that’s the truest form of that story. Those were some big revelations for me — that even with people I was righteously indignant about, in almost every case, they did more for me than they ever did to me. With Quincy, I’m nothing but grateful. Whatever happened that stood in the way of us doing a project, that was my fault. But people I did have issues with, when I look back on it, I realize those are the key people but for whom I’d probably still be in Missouri.

Is seeing things that way a function of age? I realize you wouldn’t have written this book 30 years ago, but if you had, would you have had a different attitude?

McDonald: I’d probably still be stewing over those things. Not that I still don’t: You learn to forgive and you learn to realize your part in things — then, not an hour later, you’re at a stoplight going, “That son of a bitch…” Are any of us truly capable of total forgiveness? But to get to a point with all that is important, I think, to your own serenity. Otherwise you just keep drinking the poison hoping the other guy’s gonna die.

Reiser: Mike takes responsibility almost to a fault. I’d never spent this much time with a guy who’s so evolved. I went, “Oh, I’m really a piece of crap.”

McDonald: But the point is, those conclusions, I didn’t come to them easily. I came to them the hard way.

Reiser: Unlike Mike, I enjoy holding onto my resentments: You know, in 1994, I should have said to that son of a bitch…

You ever encourage Mike to talk a little trash?

Reiser: I’m not a fan of gossip. I don’t like it about other people, and I certainly don’t want anything being said about me that I wouldn’t want shared.

McDonald: Whenever I read one of those books, as much as I might enjoy it, I’m always left with that —

Reiser: You feel dirty.

McDonald: That, and the feeling that it’s just this person’s version of it. I wonder what the other guy would say, and so you’re left kind of unsatisfied.

See, I love it when someone’s reached a point in their life and career where they’re lighting people up.

McDonald: “F— it, I’m going in.”

Reiser: I did think Stevie Van Zandt’s book was great, and he’s just totally ripping people he felt like ripping.

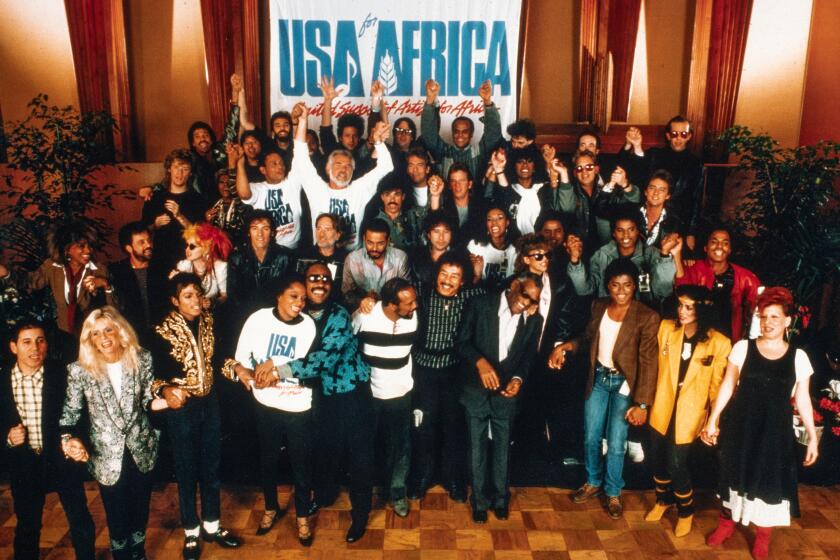

While we’re on the subject of Quincy: Why were you not on “We Are the World”?

McDonald: You’re not the first person to ask me that recently.

Reiser: Dan Aykroyd took his spot.

Lionel Richie looks back on the making of ‘We Are the World’ as seen in a new Netflix documentary.

Given your success at the time, it’s a conspicuous omission.

McDonald: I’m sure there are other people who weren’t on it. I mean, it was only a cast of thousands.

Reiser: The important thing is that you’ve made Mike feel bad about something from 40 years ago.

McDonald: If I said I didn’t give it a lot of thought, I’d be lying. There were other things I was on, like a Donna Summer session Quincy asked me to do. It was Bruce Springsteen and Stevie Wonder — I have a picture of this — and I’m standing over there looking like I was delivering sandwiches.

The unmade Quincy album made me wonder if writing this book made you mull over other missed opportunities.

McDonald: Oh yeah. And I always considered that a missed opportunity — I always regretted it. For such a fortunate person, I could f— up a good thing in a heartbeat. My M.O. was letting other people handle what I should have handled myself and then being pissed off at them. That was something I did far too many times in my life.

I enjoyed learning that the hair dye you used in the ’80s was called Chocolate Kiss.

McDonald: High-end stuff.

Reiser: I went with Don Ameche 7.

McDonald: That’s what I love about these rock ’n’ roll events with guys my age: You’re in line going in and that shoe-polish smell hits you from the guy in front of you. No one born to this world ever had eyebrows that black.

What gave you the gumption to stop dying your hair?

McDonald: I got tired of it real quick. I think in the back of my mind I had the idea that maybe it would get me out of having to make the next music video — because if I refused to do it, they weren’t gonna want me to be seen with white hair.

Of course, your white hair then became your visual trademark.

McDonald: I guess. For me, the ordeal of leaning over a sink with a towel around my neck while my wife is yelling at me — that was torturous. I said, “I can’t do this anymore or we’ll get divorced.” So I went to my hair cutter and had him do it, with the tinfoil and everything. That was even worse.

Did going back over your career make you think about why people have connected with you as a singer?

McDonald: I don’t know that I’d ever have the courage to really analyze that because I may not like the answer. Or I may find out I am the imposter I think I am. It’s kind of like staring at yourself in the mirror too long — you start to scare yourself a little bit.

Reiser: That’s one of the things that I found challenging to put into words. You say “Michael McDonald” to anybody, they go, “Oh my God, that voice!” But you can’t ask the guy, “What’s going on in your esophagus?” I realized it’s like asking George Clooney how he got so handsome.

McDonald: As someone who came into a band that was known for a certain vocal sound — Tom Johnston and Pat Simmons [of the Doobie Brothers] — I was met with as much skepticism as I was someone going, “I love your voice.” For every one of those, there was somebody who said I ruined the Doobie Brothers. “You sound like you have marbles in your mouth,” which is true.

You’ve been embraced in particular by some of the greats of R&B and soul music, some of whom cut duets with you: Aretha Franklin, Patti LaBelle, James Ingram.

McDonald: That’s been one of the most gratifying things I’ve experienced. When I heard Ray Charles for the first time I understood what soul music was. I’d heard other artists and loved them: Nat Cole and Louis Armstrong and Etta James. But it was something that was so explicit about how he approached it. Right away, you went, this guy never sings any song the same way twice — it’s a total improvisation of feeling in the moment. And that just blew my head wide open.

With pop acts like Taylor Swift cutting multiple editions of LPs and pricy back-catalog reissues, Fidelity pressing plant in Oxnard says it is ready to help the vinyl boom stay in the groove.

White singers operating in a traditionally Black cultural space can be viewed as interlopers or appropriators. That doesn’t really seem to have happened with you.

McDonald: I think a lot of that comes from the fact that when we grew up listening to music, it was very regional. Growing up in St. Louis, pretty much all the music we listened to was R&B from 10 or 15 years before us because it was passed down by the older guys. If you were in a band, you were gonna work up this Bobby Bland song that was out maybe before I was born. So I had a personal relationship with all that music because in that region, that’s what we listened to — just like Stax/Volt was a natural evolution of growing up in Memphis or like beach music in the Carolinas. Most people don’t even know what beach music is, but it was a day-to-day cultural experience for people who grew up on the southern East Coast.

When it came to writing about your family members in the book, did you feel like you needed to ask their permission?

McDonald: I did in my wife’s case because her journey in sobriety is not something I would normally ever talk about. You just don’t do that. But it was such a significant part of the story that I felt compelled to write about how it affected us as a couple. To this day, I think she’s one of the main reasons I’m sober — not because I did it for her but because she really pointed the way for me by her own example.

I was moved by your account of deciding to homeschool your son after his struggles in regular school. That wasn’t something I expected to encounter in a rock ’n’ roll memoir.

McDonald: I think parents should communicate across these perceived lines of the things we don’t want other people to know are going on in our house. I found great comfort in that with my son. He wasn’t easy, but he wasn’t terrible, you know? And I learned that by talking to other parents. All these things I was staying awake all night worrying about, I realized I’m not alone.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.