How much Beatles is too much? Our experts gorge on the new docuseries ‘Get Back’

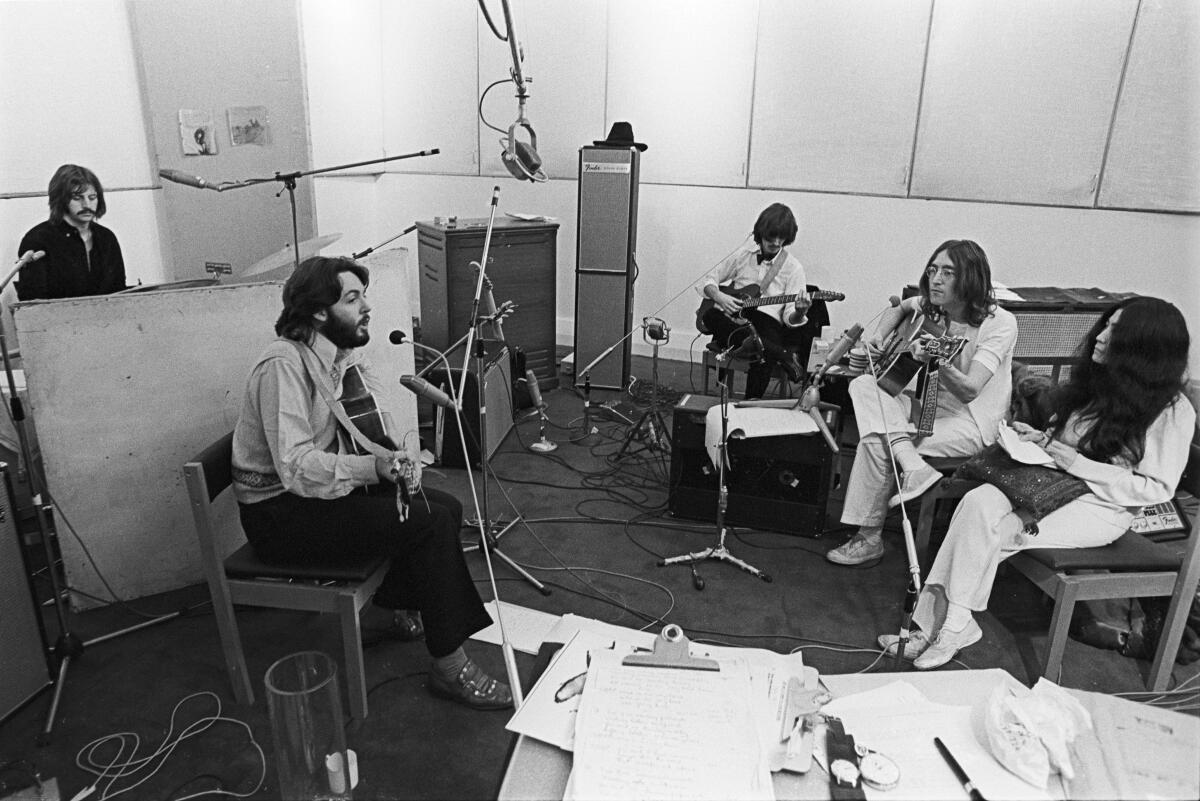

Paul McCartney sits in a chair, bass guitar propped on his knees, and plucks out a riff — nothing fancy, not yet, though he can tell he might be onto something. (His years in the world’s biggest rock band have sharpened his instincts.) Slowly — though not so slowly! — a vocal cadence begins to take shape, then a melody, then a lyric about getting back to where you once belonged. McCartney looks over at George Harrison, his band mate in the Beatles, who’s lounging across from him inside a cold London studio in January 1969, and lets his eyes sparkle ever so slightly: He’s just created “Get Back,” which will go on to become a rock classic still beloved by fans half a century later.

The scene in “The Beatles: Get Back,” director Peter Jackson’s nearly eight-hour docuseries, is just one of many that can make you feel like you’re in the room with McCartney, Harrison, John Lennon and Ringo Starr as they write and record tunes that will end up on the group’s final two studio albums, “Abbey Road” and “Let It Be,” and rehearse for the famous rooftop concert that served as the Beatles’ last public performance.

Painstakingly assembled by the Oscar-winning “Lord of the Rings” auteur from dozens of hours of fly-on-the-wall footage originally shot by director Michael Lindsay-Hogg for his 1970 film “Let It Be,” “Get Back” — which just premiered in three parts on Disney+ — revisits a contentious period in Beatles history with fresh eyes; it explores McCartney and Lennon’s complicated partnership, Harrison’s feelings of being under-appreciated and the effect that Yoko Ono’s presence had on the band. It’s also a showcase of some glorious beards and knitwear.

“Get Back” isn’t the only music documentary this year to find remarkable new life in recovered source materials; think of Todd Haynes’ “The Velvet Underground” and Questlove’s “Summer of Soul,” both of which allow us access to people and moments we might’ve thought were lost to time. But Jackson’s epic is a singular immersion. Times pop music critic Mikael Wood, staff writer Randall Roberts and columnist Gustavo Arellano gathered to discuss it.

MIKAEL WOOD Let’s start where everything ended — or at least where we’ve always thought everything ended.

So much of the hype around “Get Back” is based on the idea that Jackson’s film challenges the conventional wisdom about the Beatles’ demise; it argues that early 1969 wasn’t quite as miserable for the Fab Four as previously assumed, a revelation that in turn has been marketed as a kind of balm for fans still traumatized by the band’s breakup.

As someone born in 1978, nearly a decade after the group split, I’ve never had an emotional investment in the end of the Beatles per se. My experience of the band (which I love!) happened totally out of order; I think the first LP I pulled from my parents’ vinyl collection was 1970’s “Hey Jude” compilation. So the sense of loss people felt after riding with the Beatles on such an insane journey — for me, that’s more of an intellectual proposition than a visceral one.

Peter Jackson and ‘Let It Be’ director Michael Lindsay-Hogg explain how 57 hours of footage from 1969 tell a different story in ‘The Beatles: Get Back.’

But what about you guys? Did “Get Back’s” framing — its explicit appeal to your emotions — entice you the way it seems to have enticed others?

GUSTAVO ARELLANO I was born a year after you, Mikael, but the Beatles remain my favorite band of all time — no one else even close. I mourned their premature end once I learned about it and still do to an extent. But the framing that Jackson is using isn’t new.

“The Beatles Anthology” video/CD/book series from the 1990s already showed what “Get Back” is trying to tell us: Yeah, the Beatles broke up, but all things shall pass, blah blah blah — and wow, they were doing superhuman tunes and joking with each other even as they were falling apart! I didn’t buy it then, and I don’t buy it now. No breakup is so simple, or easy, so why try to state otherwise?

Older me wonders why Paul, Ringo, Yoko and Olivia Harrison (who’s a Chicana from Hawthorne, by the way) think it’s important to reframe the end of the Beatles as, if not necessarily happy, then definitely not sad. What does the Beatles empire gain from being as positive as possible, or reinterpreting the very messy end we slowly see unfolding here as just something that happened?

RANDALL ROBERTS I was born a few years before the Beatles broke up and was inculcated into the Beatles cult in the mid-1970s through my older sister. I love almost everything about the band except for culture’s obsession with them. I also hold a grudging admiration with the ways in which the band’s estate has retrofitted their marvelous mausoleum for each new generation of potential fans.

“Get Back” feels to me like a mix between “Song Exploder” and a reality-show challenge. The synopsis of Part 1 lays out the stakes: “The Beatles arrive at Twickenham Studios and have three weeks to complete 14 songs and a live show.” There’s an inherent drama in that angle, one aimed to draw in both newbies looking for an entry point and experts eager for minutiae.

Gustavo, as you point out, the way in which Jackson frames the nature of their disagreements doesn’t convey much new info. Early on, he beams in on one major issue — George’s second-class status as a songwriter — as a narrative driver. For a Beatles fan, to witness that power struggle and the subtle ways it played out was riveting. I loved watching Harrison demo “I Me Mine,” a song about the band’s disintegration. You can hear the anger and frustration in his voice as he sings words he can’t seem to utter sans music.

I also think that we’ve been blaming “interloper” Yoko Ono for the Beatles’ split for 50 years when obviously we should have been equally focused on Harrison’s tripped-out Hare Krishna entourage.

ARELLANO I grew up thinking Yoko was the villain that destroyed the Beatles — to the point that when “The Simpsons” parodied the idea in the episode about the B Sharps, I cheered all the way. But in “Get Back,” she’s just hanging out. Never gives any ideas, sometimes sings some songs. But I saw none of the venom I was long led to believe existed in the “Get Back” tapes. Where was the infamous anecdote that whenever Paul sang “Get back to where you once belonged,” he’d shoot dagger eyes at Yoko? Turns out it was a parody of anti-immigrant politician Enoch Powell all along.

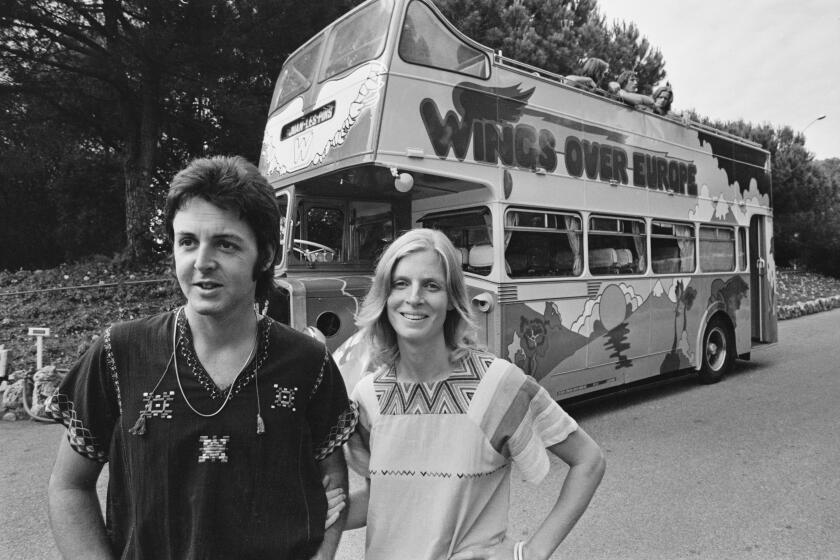

We assess 50 years of post-Beatles Paul: from DIY solo to Linda and Wings, from Stevie to MJ to Rihanna and Kanye.

Maybe the anti-Yoko anger happened later, as John got even more into her. But it wasn’t here. As Randall points out, George had two hangers-on. And Linda Eastman was by Paul’s side almost as much as Yoko, yet she never got anywhere near the blame Yoko did.

But I wasn’t surprised about George’s seething anger. Hell, he was already communicating his gloomy-gus vibes on “With the Beatles” way back in 1963 — a geologic age, in Beatles time — with his first composition, “Don’t Bother Me.”

WOOD Let’s talk more about “Get Back’s” roots as a protest song.

One thing that struck me, especially in Part 1, was how cloistered the Beatles seem at this point in their career — they’re living deep inside the rock-star bubble, with every need met by the many members of their staff. The scenes inside Twickenham are almost claustrophobic in that way.

At the same time, we keep seeing the band with their noses in newspapers, and not just to see what the gossip columnists have said about them now. They’re hungry for news from the outside world; they’re worried in particular about what Powell is fomenting in England.

I like the specificity of the message in the early version we hear of “Get Back,” where Paul is satirizing Powell’s anti-immigrant rhetoric. It’s not vague peace-and-love stuff; it also risks being misinterpreted, which is always exciting for an act as popular as the Beatles were.

Can either of you imagine the band sticking with this idea for “Get Back”?

ARELLANO The Beatles were always quiet progressives. They refused to play segregated audiences in the South as early as 1964, they had the Eastside Chicano band Cannibal & the Headhunters as openers for their Shea Stadium and Hollywood Bowl shows. McCartney says “Blackbird” was his allegory on the civil rights struggle in the U.S.

But they never wanted to be too radical. “Revolution” would be ridiculed by progressives today for sounding as though it’s against activism. There’s a reason the National Review ranked it as the seventh greatest conservative song of all time (“Taxman” was No. 2).

The Beatles weren’t the Kinks or the Animals — brilliant commentators on class in Great Britain; they were worldwide ambassadors of peace and love. So no way was Paul going to be so specifically against Enoch Powell for long.

ROBERTS I thought their brief conversation about the poetics of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech was fascinating, as was Lennon’s brief reference to it as Billy Preston first enters the studio.

For me, the biggest surprise of Part 2 was Preston, whose keyboard work gave wings to the band’s increasingly electrified sound. The conversation the Beatles have about asking Preston to join as a fifth Beatle was drool-worthy, as was Harrison’s cheeky idea to invite Dylan to join the band. Little did we know that the seeds of the Traveling Wilburys were planted in 1969.

ARELLANO Preston lived up to the hype about him and the “Get Back” sessions — that everyone shaped up once he showed up. They’re happier and sharper, and the rooftop concert crackles, down to McCartney ridiculing the bobbies who shut them down. We’re all familiar with the rooftop tracks that landed on the original “Let It Be” album and on “Anthology 3,” but to see the show in its entirety was incredible. There’s a joy built of age and relief that I didn’t expect.

WOOD The band’s sound on the roof really is something else. They’re somehow so tight and relaxed at the same time; the harmonies are crisp but the grooves swing. And Preston adds so much detail and energy.

ARELLANO That’s why it surprised me that he’s reduced to just a couple of blocked background shots. Didn’t Michael Lindsay-Hogg — in his smarmy, cigar-chomping wisdom — think maybe he should have one of his 10 cameras trained on the invited guest?

I’m seeing all this as a Beatles fanboy, and it still was too much for me to see without getting distracted. So who is this for? Us diehards? Or did the Beatles’ estate task Jackson with trying to grab some new fans in the process?

WOOD In my mind the series’ length — and its occasional tedium — make it the ultimate in diehard fan service. Does anyone not already in the tank really want to see the Beatles play “I’ve Got a Feeling” 37 times?

Like all documentaries where the subject is also a producer (think of recent movies about Billie Eilish, Lady Gaga and Taylor Swift), “Get Back” has to be thought of at least a little bit as a commercial; let’s not forget that it arrives accompanied by a pricey coffee-table book and a lavish box-set reissue of “Let It Be,” neither of which is intended for the casual fan.

So what’s it advertising beyond product? I think the heart of the movie is the endurance of John and Paul’s unique relationship, how close they remained even as their worldviews diverged. You can hear it as they talk about George’s quitting; you can see it in the way they work, bicker, joke, egg each other on, cut each other down and sometimes stare into each other’s eyes like two people in love. McCartney, I’d imagine, wants the world to know more about that bromance, which softens his reputation as the group’s operator.

That said, it’s not always flattering in the way it depicts him — though Jackson, a guy with plenty of experience presiding over complicated creative endeavors, pretty clearly sympathizes with McCartney’s desire to impose some discipline on the band.

“Daddy’s gone away and we’re alone at the holiday camp,” Paul says at one point, referring to the death not two years before of the Beatles’ manager, Brian Epstein.

What’s most moving about the series is seeing how music — whether it’s a cover of an old Hank Williams or Isley Brothers song or an original just beginning to find its form — repaired all their divisions (at least for the moment). I loved watching them crowd into the control room after every take to hear what they’d just laid down. The excitement is so pure.

ROBERTS Like you, Mikael, I question the lack of editorial freedom that comes with having the estate involved in the production. This series is the sanctioned story and hits all the right plot points. But wouldn’t it be wonderful if they now gave this same 60 hours of footage to, say, Werner Herzog so he could make a documentary about the true hero of this film: roadie, cigarette boy and human music stand Kevin Harrington?

ARELLANO I’ll see your Kevin, Randall, and raise you a Mal Evans, who I always thought from the chroniclers was an oaf but was far from it. Good bloke!

For all the Disney+/Beatles hype, Paul — pardon the pun — just can’t let these sessions be. He tried to torpedo Phil Spector’s Wall of Treacle remixes before the release of the original album (although who can blame him?). The original film has never been released on DVD. In 2003 he released “Let It Be … Naked.” Now this.

We as fans are beneficiaries of Paul working out his trauma. But he should just admit what John, George and everyone else who was there has said almost from the start: The “Get Back” sessions were a disaster, the beginning of the end for the Beatles — and that mostly falls on Paul.

But look at what this disaster is: gorgeous, soulful, ever-listenable music that wins new fans anytime anyone with a heart and good taste listens to it.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.