In stunning new documentary, Todd Haynes makes the Velvet Underground come impossibly alive

Though the most famous incarnation of the Velvet Underground was only around from 1965 to 1968, its influence on the direction of rock music is incalculable.

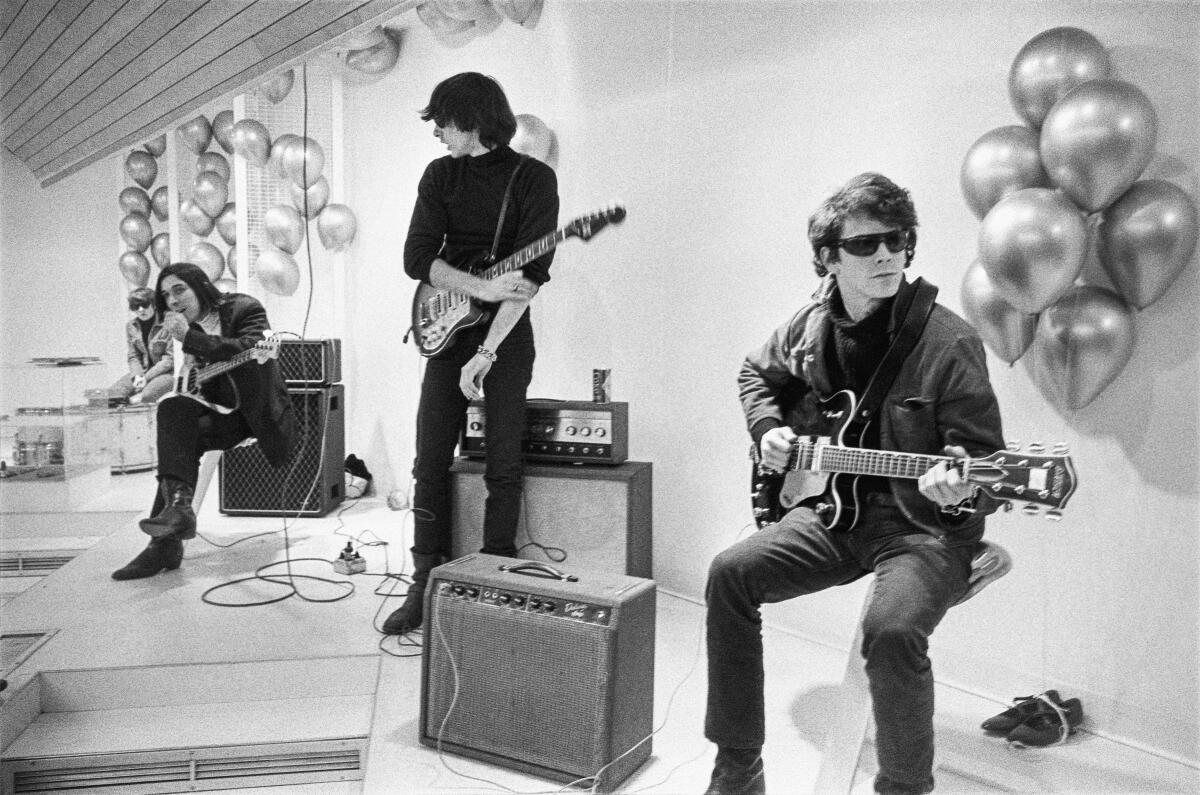

Founded in New York by Long Island-born Lou Reed and Welshman John Cale, and soon joined by Sterling Morrison and Maureen “Moe” Tucker, the quartet and its beguiling sometimes-singer, Nico, served as the house band at Andy Warhol’s art space the Factory, where their glorious, drone-heavy din and wild Warhol-created light shows were a magnet for a cross-disciplinary posse of experimental filmmakers, painters, models, musicians and hangers-on.

On Friday, “The Velvet Underground,” director Todd Haynes’ visually stunning, musically mind-blowing documentary on the band’s origins, influences and work, will premiere in theaters and on Apple TV+.

Starting in 1967 with “The Velvet Underground & Nico,” which featured as its cover art Warhol’s famous “peel slowly and see” banana sticker, the band released four studio albums. Though they were a commercial failure, their transgressive sound on songs such as “Heroin,” “All Tomorrow’s Parties” and “Venus in Furs,” combined with the delicate ballads “Sunday Morning,” “Pale Blue Eyes” and “Candy Says,” helped crack open a thematic world where countless inheritors now reside. While West Coast hippies were celebrating peace, love and LSD, the Velvet Underground was writing and performing songs about shooting heroin and engaging in S&M, paving the way for future outsiders to establish the aesthetics of punk and new wave music.

As the years passed, those albums would ignite the muses of countless artists, including David Bowie, R.E.M., Nirvana, Joy Division and Big Star, all of whom covered Velvet Underground songs.

Singing great Dionne Warwick, riding the viral success of her Twitter persona, has helped her son open a sound bath and meditation center in Venice.

“The Velvet Underground” is the first feature-length documentary for the acclaimed Haynes (“Safe,” “Carol”), whose prior music-focused projects revealed the creative depths of his fandom: “Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story,” a controversial short film that used Barbie and Ken dolls to represent the sibling soft-rock duo; “Velvet Goldmine,” set in early ’70s glam-rock London; and his kaleidoscopic Bob Dylan biopic, “I’m Not There,” featuring six different actors playing Dylan.

The Velvets project sprung from a desire on behalf of Reed’s widow, Laurie Anderson, and Universal Music Group, which owns the band’s masters, to renew a conversation about the Velvet Underground’s legacy while taking advantage of the footage and material housed in Reed’s and the band’s archives. (Reed died in 2013.) Anderson had identified Haynes as a potential director, and when the ask arrived, Haynes didn’t hesitate.

“I said, ‘Absolutely. Hands down.’”

Featuring new interviews with surviving band members Cale and Tucker, the late filmmaker Jonas Mekas, inhabitants of Warhol’s art studio the Factory, musicians Jonathan Richman, La Monte Young and his artist-wife Marian Zazeela, Nico collaborator Jackson Browne and others, “The Velvet Underground” doesn’t just document the complicated characters at the center. Through visually striking use of tiling and split screens, via Warhol’s single-shot experimental films, including “Empire,” “Sleep” and the many “Screen Test” shorts, the documentary augments the central story with layers of visual cues and accents.

Cale, 79, said via email that after seeing the completed film, he was struck by “Todd’s ease and charm in navigating the channels of each member of the list of characters he encountered on the journey — many of whom have passed on. He set the table for the subject to fill the screen and take over all the senses without use of the standard documentary format.”

Although this period of his life was etched into his memory, Cale added: “Seeing this film reminded me of the magnitude of ‘others’ that were not necessarily front and center, but played a valuable role in carving out a space in spite of mainstream constraints. What Andy provided most was the springboard and encouragement to live dangerously outside the margins.”

Haynes sat down to talk about “The Velvet Underground” from Portland, Ore., via Zoom.

When did you first hear the Velvet Underground?

I started listening to them when I was at Brown University. I’d already been listening to Roxy Music and David Bowie and Patti Smith and going to punk clubs in downtown L.A. As is true for so many people when they discover the Velvet Underground, I was already attracted to genres of music that would not have existed without them.

With this film being driven by the Velvet Underground’s music, what was your approach to scoring it?

It was our hope that the film would be led by the images and the music, not the interviews, and that you’d leave feeling like you almost dreamed the words and the stories. But we also spend a great deal of time before getting to the first Velvet cut [“Venus in Furs”] in the film. We spend a lot of time excavating the musical origins and avant-garde music that John Cale was exploring with La Monte Young, and a lot of the early Lou Reed compositions where you’re seeing the seeds of what the Velvets might sound like.

All these things almost make you forget that you’re watching a movie about the Velvet Underground. Then you get to the Velvets song, and by holding it back a bit I think it lands more powerfully. It’s almost like “The Wizard of Oz,” where you watch Dorothy and her friends come together down the Yellow Brick Road, and then they’re off to Oz because they’ve found each other and they know where they’re going.

Why did you decide to restrict yourself to firsthand witnesses instead of bringing in experts or outside musicians to augment the band’s story?

I didn’t want to make a movie that told you why the band was great. I want to make a movie that showed you why they were great and let you hear it. The biggest challenge for music that has finally gained its rightful place in the canon is to make it be heard with the violence of its freshness.

It’s almost like when you go to the library — and I did this when I was doing a film about Arthur Rimbaud in college as a thesis project. There is [pinches his fingers] this much original writing of Rimbaud, and then there’s shelf after shelf of analysis and interpretation.

It’s comparable to the Velvet Underground. There are so many people who could tell you why they’re great, why they matter, but it’s overwhelming. It could go on and on, and where do you stop? So it simplified the list of interviews.

As the film proves, Jonathan Richman was just about the only musician you needed.

Seriously. He ends up qualifying as fan, musician, critic and, of course, witness. I knew he was there, but I didn’t know how profoundly Jonathan was there, going to 60 to 70 shows in Boston. Him being brought into the bosom of the band, in turn, revealed a lot about the band. It was hard to imagine them being so generous and open to this teenage musician.

Mick, Keith, Ronnie and Steve Jordan on saying goodbye to Charlie Watts, filling a legend’s drum seat and why it was ‘the right decision to keep going.’

There are so many ways to watch this documentary. How did you come upon the idea to use tiling, multiple frames and parallel movement to tell the story?

The way into telling this story was, by definition, going to be different from other rock documentaries. The decision to only interview people who were there was my own, but there were other things that we inherited. There are no traditional kinds of visual materials that exist of this band — concert footage, interview footage, promotional material, etc. — like there would be of so many other bands that are this influential.

What you do have is this band appearing in the work of Andy Warhol. He was so deeply embedded in and bound up in the avant-garde filmmaking that was going on in New York, and he had an inherent curiosity about breaking down the boundaries between mediums.

He was just one example of what was happening among a lot of different artists — but no one was as central and influential in creating a scene as Andy. So it was handed to me as, “This is an extraordinary visual culture — and it’s relevant to this story. Let’s visualize this time and place, and let’s let it visualize the music.”

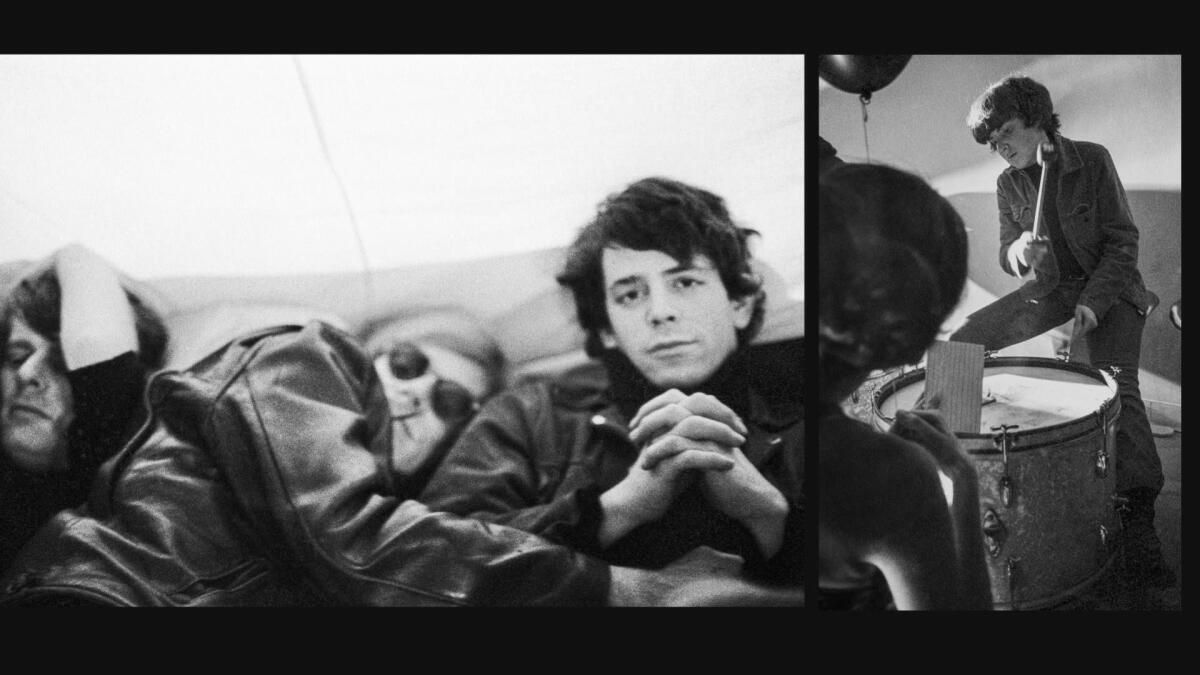

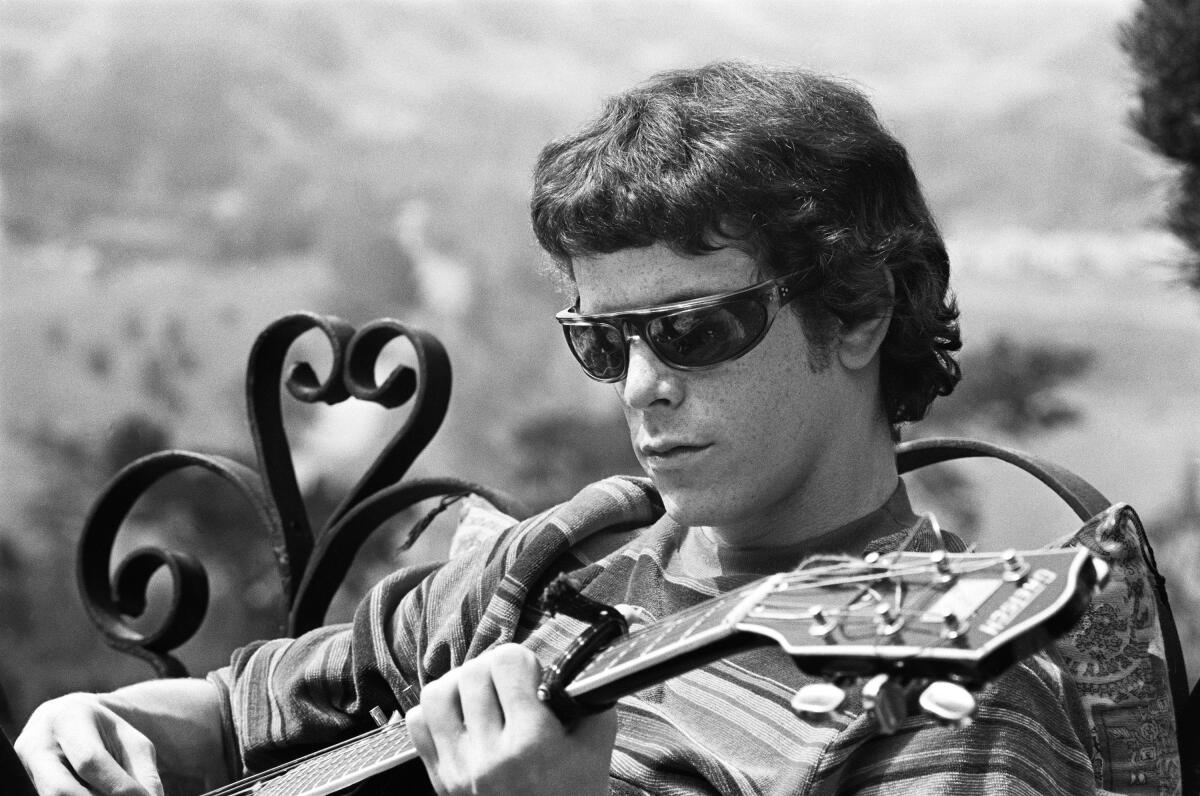

Lou Reed isn’t always a sympathetic character in “The Velvet Underground.”

He’s inherently complex and full of a lot of aggressive defenses and shields. But some of that aggression is essential to his work as an artist. He employs that language, that toughness, that coolness, in his creative language and his stage persona.

I didn’t realize that his main goal as early as high school was to be a rock star.

I didn’t know that either about his high school ambitions and how tough-minded he was about wanting to be in the spotlight. But then he’s the same person who, when trying to make a hit record, would [in 1964] compose “The Ostrich,” which was an all-out garage-rock noise song.

That is a fascinating contradiction in him, and contradictions, of course, describe a lot of really great and compelling creative people — the way they shuffle those contradictions around in their work.

You hear it in the testimony of people closest to him, like Shelley Albin, his girlfriend in college. They had the first real, sincere relationship of his life together before some of his volatility got the better of him. She was an artist and they lived as an artistic couple and swapped paintings and poems. And Lou’s explorations into sexuality, going into dark and unknown places — his sexual curiosity was also always there, even in his high school years. He was so fully formed. He wrote “Heroin” in high school. It’s phenomenal how coherent he is from the beginning.

I’m surprised that artists as strong-willed as Cale and Reed would allow Warhol to invite a singer like Nico into the fold, who for all her allure couldn’t really hold a note.

I think [Warhol confidante] Paul Morrissey may have even had a stronger role in this, and felt that for commercial or presentational reasons, or for the glamour of the band, they should have Nico be this singer.

What’s so remarkable is that Nico is finding her voice. And it wasn’t a traditional kind of voice, but Lou and John and Sterling all helped find this way of using Nico so that the first album now seems inconceivable without her.

Who were you thinking of as the audience when you were plotting this story?

It is a balancing act between trying to introduce this time and band to new listeners, and yet not oversimplify the richness of what they were.

This may or may not appeal to every audience, but I think it lives up to the incredible risks that this band took and why they are considered so ahead of their time. They were talking about things that nobody else in the 1960s was talking about: What it’s like to live in your own skin, to feel ambivalent about life, to feel dread and isolation and sometimes to want to nullify your life. They had a non-affirmative view of the world.

They opened the doors for so many other artists to talk about vulnerability and uncertainty and pain.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.