Jackson Browne on cancel culture, his ‘shelf life’ and how to survive rush hour in L.A.

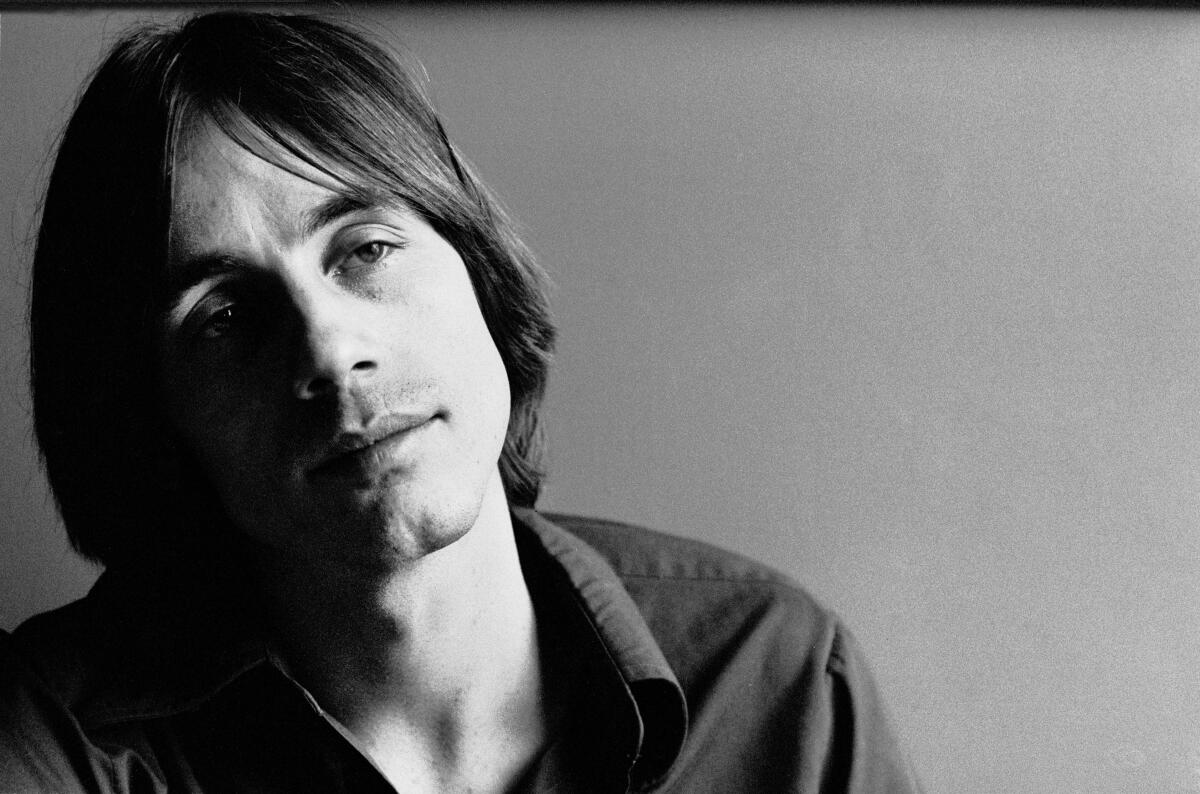

Jackson Browne knows people think he’s past his prime. Or “way out over my due date,” as he puts it on his new album.

“I’m talking about shelf life,” he says. “But I think a lot of stuff is still good after the date that’s printed on the package.”

At 72, the musician is grappling with what his life will amount to — that’s really what the lyric is about, he says: “An admission that you’re supposed to have settled stuff by this time.”

It’s not that he had a vision for what life in his 70s would be like; he’s never looked that far into the future. But he has always been a self-reflective sort, unafraid to question whether he’s squeezing all of the juice out of the fruit. Even one of his first hits, “Doctor, My Eyes” — released in the midst of the Vietnam War — told the story of a man puzzling over how to digest the hardships of the world.

Browne’s eyes are still wide open on “Downhill From Everywhere,” the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductee’s first collection of new music in six years. On the album, the singer-songwriter takes typically forthright stands on ocean pollution, immigration rights and gay marriage. Though he grows somber when he discusses current events, Browne also seems to have softened with age — exuding less an obstinate attitude than an equable one.

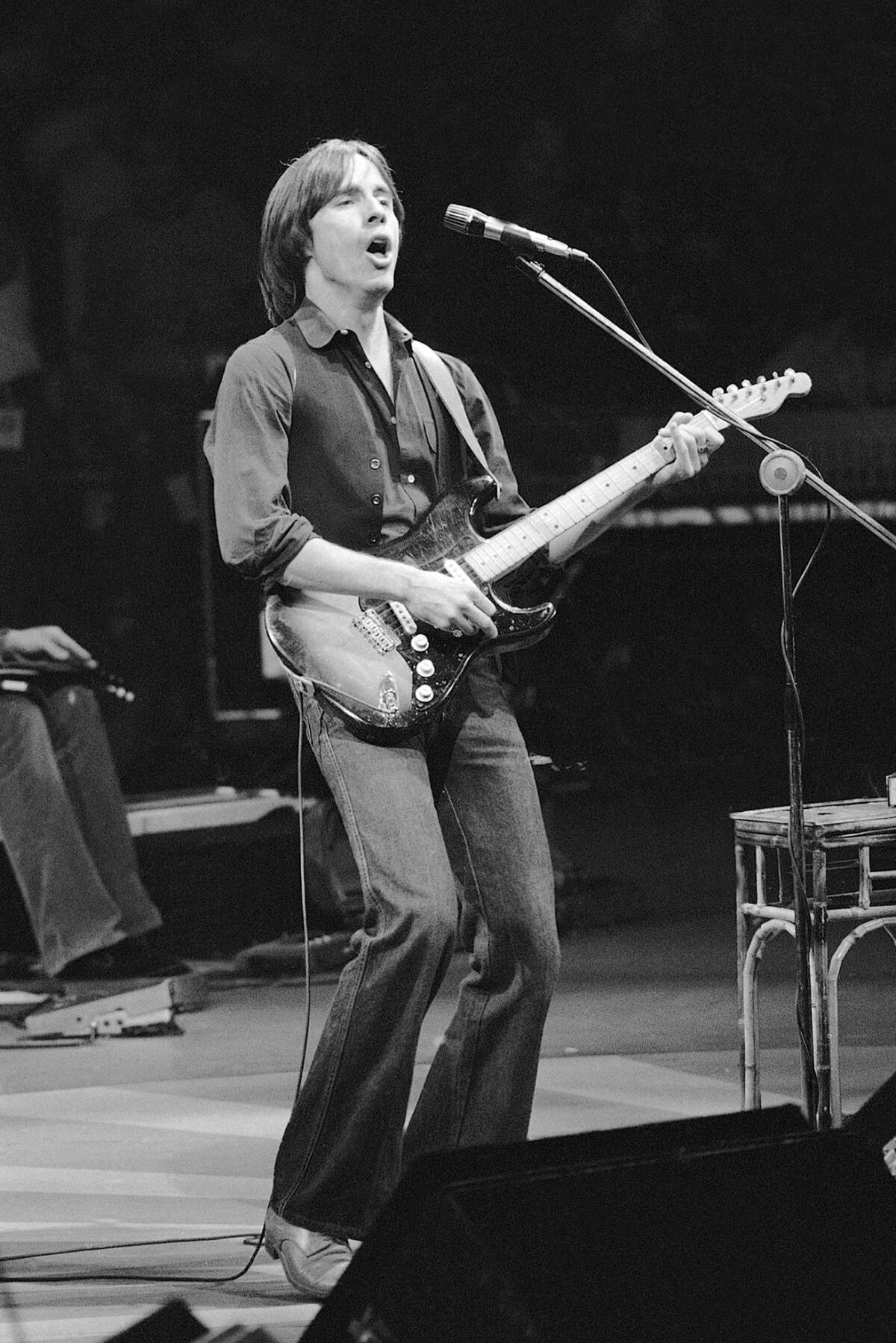

In the late ’60s and ’70s, Browne established himself as one of Laurel Canyon’s preeminent songwriters with now-standards like “These Days” (written when he was 16), “Take It Easy,” co-written with the Eagles’ Glenn Frey and “Running on Empty.” Back-to-back smash albums “The Pretender” and “Running on Empty” made him a full-fledged rock star, but gradually he would pivot his music and career away from pop philosophy and toward the political. He organized “No Nukes” benefit concerts against nuclear weapons and nuclear energy alongside Graham Nash and Bonnie Raitt in 1979 and condemned U.S. policy in Central America on his 1986 album “Lives in the Balance.”

Browne still champions numerous causes; he was performing at a fundraiser for the charity God’s Love We Deliver in March 2020 when he became one of the first stars to contract COVID-19. He likes experimental theater — he’s wearing a shirt from Tim Robbins’ Culver City-based the Actors’ Gang nonprofit — and seeing live music with some of the young artists he’s befriended, like Dawes, Jenny Lewis, Inara George and Phoebe Bridgers. (Earlier this year, Bridgers enlisted Browne to duet with her on a new version of her song “Kyoto,” and she in turn then appeared in a music video for his song “My Cleveland Heart.”)

Browne, who lives in Los Angeles’ Mid-City with his longtime partner, Dianna Cohen, has two adult children from previous marriages.

This week, he heads out on a three-month tour with James Taylor that will stop in Anaheim in October. The Times spoke with Browne at his Santa Monica recording studio, Groove Masters, where Bob Dylan, Frank Ocean and David Crosby have made music.

What made you decide to record an album after six years?

The way you pose the question presupposes that there’s getting ready. I’ve had a studio for 30 years. I’m always doing something. It’s more like there’s a residue you gather or a condensation that gathers.

You once said that your standards plague you. Do you still feel that way?

I think I was talking about the fact that it’s not a good idea to try to write a song as good as some other song you’ve already written. Because when you wrote that song that you thought so highly of, you weren’t holding it up to some other standard; you were just trying to write something new. Look, I’ve got a high opinion of some of my songs, but to write something new you have to forget everything you’ve ever done.

You sing on this album about being concerned for the future your children will inherit. What scares you?

I am in a state of grief for the world that my kids are inheriting — my grandson. Elephants and tigers are in danger. The ocean’s got dead spots in it. The reefs are dying. The natural world’s ability to bounce back from what we’ve done is an existential threat. ... We’ve got these electric cars, so why don’t more people have electric cars? Why don’t we phase out fossil fuels? They won’t until they’ve sold us every last thing they have. I don’t get to talk about this stuff very much in conversation. So for me, the challenge is to write a song that people don’t mind hearing and that helps galvanize some sort of feelings or helps them find some resolve.

When you started more politically themed music in the 1980s, were you worried about losing your audience?

I know it was considered problematic by some people in the music industry to talk about politics. But they were never my people. You hear people like, ‘Oh, he’s losing an enormous part of his audience by talking about this.’ They’re talking about sales and s— like that. That never mattered to me anyway. Please.

It didn’t matter to you at all?

When you sing about stuff that nobody knows anything about, the recognition for what you’re doing is gonna drop off. At the same time, a bunch of other things were happening that are probably more responsible for the popularity declining, like punk music. You’re just not 25, now you’re 33, and there’s a completely different aesthetic going on and an attitude about everything that’s come before, rightfully or wrongfully dismissing you.

Many of your reviews cite you as being a really serious person. Do you think that’s fair?

I’ve had people remark on that to me, like, “Oh, I expect you to come in with sheaths of newspapers and notes and stuff.” There was this great remark that Don Was made. He was asked about a song that was political, and he said, “Oh yeah, we’re kind of political. Well, we’re not like Jackson Browne, where we’re with a pointer and talking about troop movements.” It was a funny thing to say.

I was playing at a Christmas show in Asheville a few years ago, and I sang this song about war called “The Drums of War.” Later, I was talking to one of the guys on the show and said, “Maybe I kind of sandbagged these folks. You think I shouldn’t have sang them a song about the war [at] Christmas?” He said, “People know you, Jackson. They’re not gonna be shocked that you sing a song about the war.”

How do you get your news?

I’m just kind of old school: I read. I can’t stand television. Even calling it television shows I come from another century. There are newsletters I get and books, and I really like radio. KPFK Pacifica. In L.A., I try to drive when my programs are on. I don’t mind rush hour because the Tim Ferriss program is probably on, and it’s a good way to spend an hour.

You’ve developed relationships with a lot of younger artists. How did those friendships start?

That’s the music that really moves me. I feel really lucky to know all these people, and I guess I know them because I go to their shows. I met Phoebe at a party, but I hadn’t heard her play. It was a birthday party for [Australian singer-songwriter] Tal Wilkenfeld at an escape room. I was sure we were gonna escape, but we didn’t make it. Funnily enough, the room was about a pandemic. But it was hard to figure out. But later, when I heard her music, I went, “That’s Phoebe. That’s that girl I met. Holy s—.”

What did you like about it?

If I want to use the word “gratitude” in a sentence, it would be about artists like Taylor [Goldsmith, from Dawes] and Phoebe, who are bringing an emotional literacy and prowess with words to rock lyrics again. It hasn’t been absent; Lucinda Williams and Randy Newman have been there all along. But when you see somebody young applying themselves to those kinds of skills, it’s encouraging because it makes you think that is on the rise and that a more youthful segment of the population will be exposed to that.

Did any musicians serve as mentors to you when you were young?

David Crosby agreed to sing on my first record. He absolutely showed me how to record — how to multitrack vocals. He praised me to others and to myself, and that was really important. I feel a great debt of gratitude to David.

But you no longer speak to him?

That’s true. He said nobody he’s ever made music with will talk to him anymore. I would point out that his son makes music with him, and that’s really what’s at the heart of his productivity right now, is his great relationship with his son. I don’t really want to go into the details of why we’re not talking.

There was a good documentary made about him recently. Do you ever think about being a part of a film like that or writing a memoir?

I’ve thought about it because it’s been proposed. I may eventually not be good for much else, so I’ll leave myself enough time to sound off about stuff. I kind of feel like I don’t know anything.

I’m sure people would love to hear your stories — and about dating the likes of Nico, Joni Mitchell and Daryl Hannah. Carly Simon wrote a really good memoir about her marriage to James Taylor.

Who’s interested in that though? Who’s interested in Carly talking about James?

Uh, me? A lot of people!

I’m not very interested in that stuff. Have you read Linda’s [Ronstadt] book? Now that’s a good book. It’s about music. Yes! People don’t want to know about Jerry Brown and Mick Jagger and all of the people Linda had relationships with. Besides, you have to be a really good writer. And I can’t even write a postcard.

What are your thoughts on cancel culture?

I’m not very aware of cancel culture, because I’m basically helpless about social media and the kind of quick, fast-breaking news about s—. That washes over me. I’m concerned that “canceled” has become a reflexive thing. My version of cancel culture is just turn it off or change the channel.

To use an example involving people you know, Phoebe Bridgers and Mandy Moore — they were part of an investigation alleging that Ryan Adams was emotionally and verbally abusive. As a result, some say he should be canceled.

I think powerful men have been taking advantage of their status with women and that should stop. ... I think it made a big impression on everybody that [Bridgers and Moore] came forth and talked about it. That’s their right and their responsibility to tell the truth and why we like their work.

I worry about [cancel culture] though because there are examples of actors, supposedly, who I think are tremendously gifted and I don’t know what all they did. ... In some cases, it sounds really bad. In some cases, it sounds like, really? They patted somebody on the butt and so we should not see this person’s movies now? I don’t know. I’m not just trying to wriggle out of your question. I’m just trying to say that I’m actually not a good person to [talk about this] because I’m so uninterested in that stuff. I wouldn’t watch the O.J. trial.

What are you hoping your fans will take away from your new album?

You mean, you want me to boil it down? It’s not for me to say. There are no CliffsNotes for these songs. I’m not that self-conscious. I’m not worried about what people are gonna think about me. This is not an ad for myself. This is a collection of songs with me really trying to express myself.

So you don’t think about how you’ve evolved musically?

Honestly? The things that I think about are trying to sing in tune and making the song sound good.

Why keep making new music?

[Laughs] I just thought that this morning. There’s so many other things going on. What could possibly be a more glacial f—ing process than writing a song about climate change, for instance? What it gives me is a song to sing that can be sung on an occasion, and sometimes that occasion is where people have gathered together to do something about something. I like the way I just said that, because it’s very all-inclusive. It may sound like I’m being vague, but I mean it gives me a song I can sing that reaffirms what I think.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.