Rudolph Isley, co-founder of R&B stalwarts the Isley Brothers, dies at 84

Rudolph Isley, a founding member of the R&B institution the Isley Brothers, died on Wednesday. He was 84.

A publicist for the group confirmed Isley’s death. No cause was given.

“There are no words to express my feelings and the love I have for my brother,” said Ronald Isley in a statement. “Our family will miss him. But I know he’s in a better place.”

Rudolph, the second eldest son of the Isley clan, and brothers O’Kelly and Ronald formed the vocal harmony group during the dawn of rock ’n’ roll in the late 1950s. They spent the ensuing decades nimbly navigating shifting styles, building a formidable body of work in the process.

Primarily a backing singer in the Isley Brothers, Rudolph retired from the group in the late 1980s, but he played a central role during the first 30 years of their existence, a period when the Isleys were one of the biggest acts in R&B.

The Isley Brothers didn’t pioneer styles so much as crystallize their essences, on singles that turned into enduring classics. Their biggest hits — “Shout” and “Twist and Shout,” which arrived in the late 1950s and early 1960s; “This Old Heart of Mine (Is Weak for You),” a smash during Motown’s heyday in the 1960s; “It’s Your Thing” and “That Lady,” two keystones of 1970s funk — lived on not only through constant radio airplay but also through covers and sampled interpolations by the likes of the Beatles, Rod Stewart, Public Enemy, Ice Cube, the Notorious B.I.G. and Kendrick Lamar.

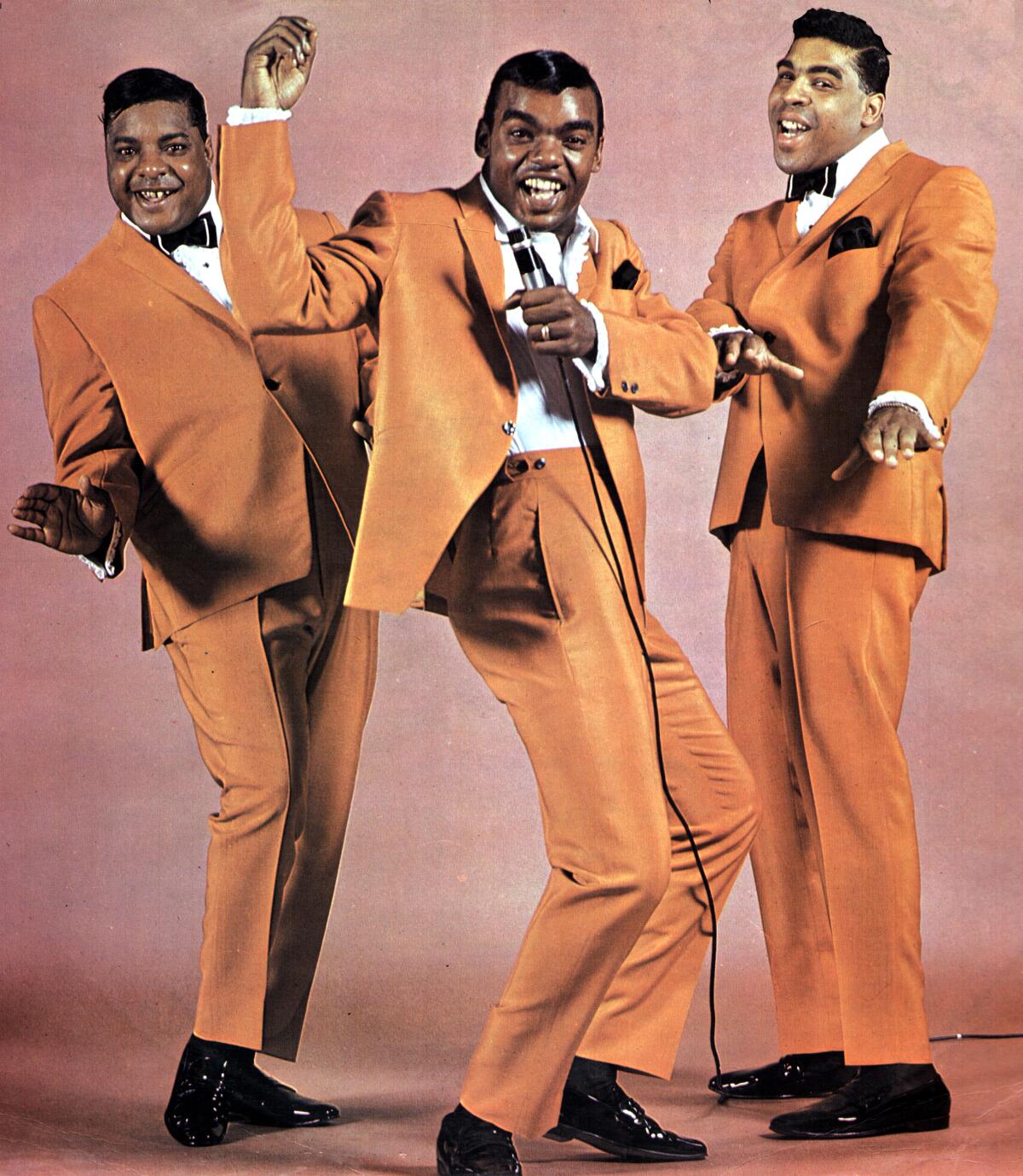

During their earliest years, the Isley Brothers balanced showbiz standards with gospel-inspired R&B, a blend that led them to their breakthrough single, 1959’s “Shout.” The frenzied call-and-response raver became a garage-band standard — rockabilly singer Dale Hawkins told music historian Elijah Wald, “Back then, if you didn’t play ‘Shout,’ you might as well stay home” — that was later immortalized by the fictional R&B band Otis Day & the Knights in the 1978 comedy “National Lampoon’s Animal House.”

“Twist and Shout,” the Isleys’ next hit, also became a standard thanks in large part to a cover cut by the Beatles, a version that received an additional run on the charts 24 years after its original release with its inclusion in the John Hughes teen movie “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.”

The Isleys’ time at Motown was brief, yet their biggest hit for the label, 1966’s “This Old Heart of Mine (Is Weak for You),” embodied the ebullience at the heart of the Motor City beat. After a transitional period ushered in by the hard soul of 1969’s “It’s Your Thing,” their first hit single on their own label T-Neck, the group dabbled in politically conscious progressive soul before the addition of three younger family members — brothers Ernie and Marvin, plus Rudolph’s brother-in-law Chris Jasper — transformed the group into their second, arguably most influential incarnation: flamboyant funk-rockers with a penchant for slow jams.

Although the pop hits didn’t dry up — “That Lady,” the first single from the expanded Isley Brothers, went into the Top 10 in 1973, with “Fight the Power” replicating its success two years later — Isleys 2.0 ruled the R&B charts in the 1970s. Their LPs — typically one side of funk, one of smooth soul — contained the grooves that would later power such hip-hop classics as Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” (“Fight the Power”), Ice Cube’s “It Was a Good Day” (“Footsteps in the Dark”) and the Notorious B.I.G.’s “Big Poppa” (“Between the Sheets”).

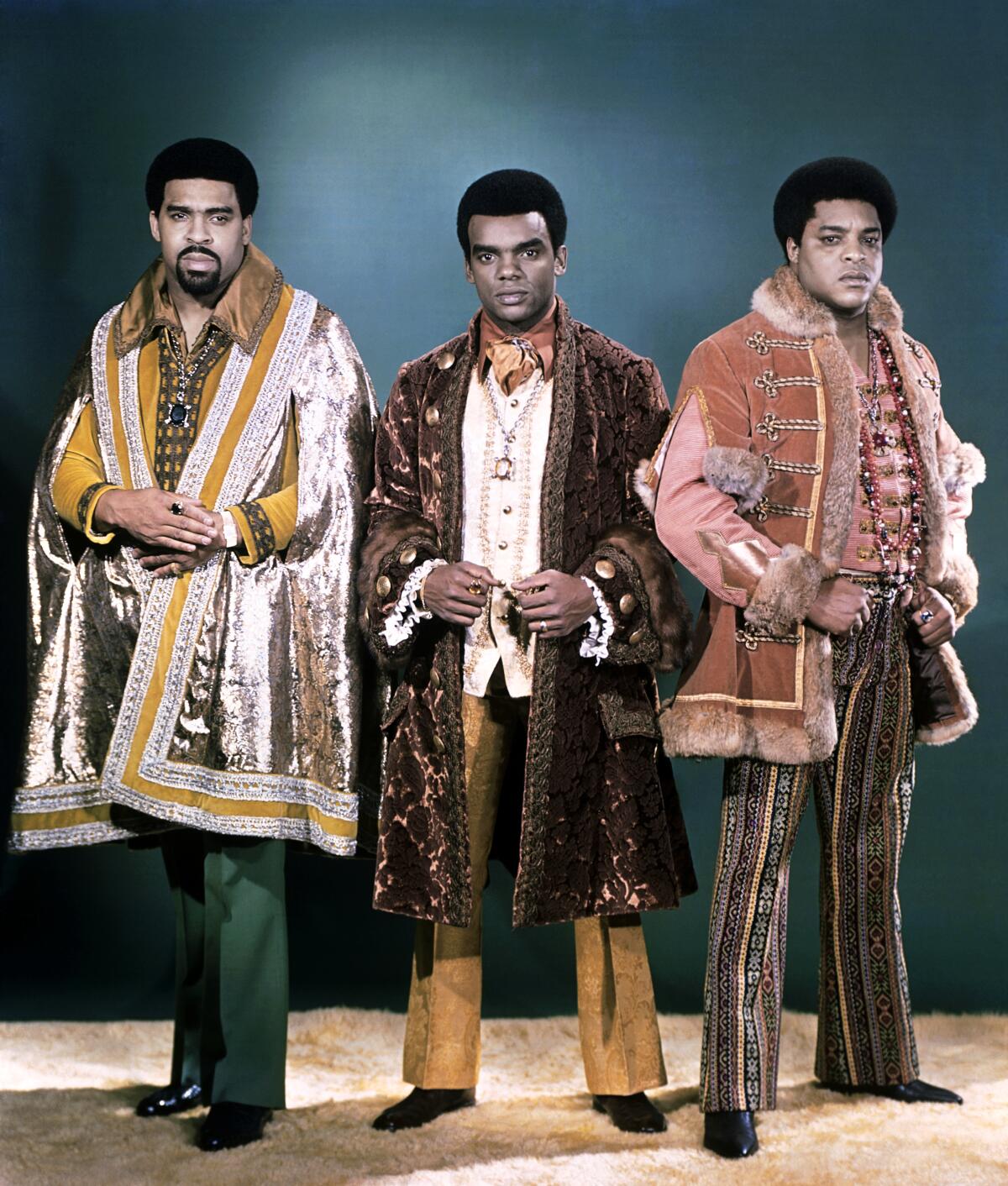

At the peak of the Isleys’ fame in the 1970s, Rudolph Isley could be an imposing figure. Big and burly, he sported fur-lined stage costumes created by renowned designer Bernard Johnson, outfits accentuated by a walking cane. Engineer John Holbrook, who worked on a few Isley Brothers studio albums in the late 1970s, remembered: “At times, it got pretty heated within the family, and they’d be yelling at each other. They were big, scary guys. Rudy was the giant and kind of intimidating.”

According to a memoir by his daughter Elizabeth Isley Barkley, “There was an ‘unspoken’ understanding that my dad was the overseer of the group. He was the one who gave final approval of what was to be.” That approval didn’t always come easily. Holbrook recalled, “One time, they’re working at Bearsville and there’s a big family row, and we can see them really going at it. And then we see Rudy storming into the control room and going for the briefcase,” a bag the engineer and his colleagues knew held a revolver. “And he opens it and takes out … a cassette!”

The fight underscored a simple truth Holbrook learned: “I did three albums with the Isley Brothers. At that point, I said, ‘I’d like to get a bit more of the action.’ Forget it, it was a brick wall. You’re dealing with a family business, and you’re not family.”

That family business started in 1954, when former vaudeville entertainer O’Kelly Isley Sr. and his wife, church pianist Sallye Bernice, assembled their children Rudolph, O’Kelly Jr., Ronald and Vernon into a vocal harmony group in their home in the suburbs of Cincinnati. Rudolph was the second oldest of six boys; born July 1, 1939, he arrived two years after O’Kelly Jr.

The four brothers initially sang gospel music with their mother, but their father steered them toward the supper-club stylings of the Mills Brothers; the boys themselves were drawn to the earthy R&B of Billy Ward and His Dominoes. With Vernon singing lead, the group was soon performing anywhere there was a stage — school, church, talent shows. In 1955, tragedy struck, as Vernon was killed after being hit by a truck; the brothers carried on with Ronald as their lead singer, developing a lively stage show that complemented their R&B and enlivened their repertoire of pop standards.

Early in 1957, the Isleys left Cincinnati for New York City, spending the next two years working the Eastern seaboard’s R&B circuit while cutting singles for tiny labels. None of the trio’s early records made a deep impression, but the Isleys could get work due to their spirited performances. One of those shows attracted the attention of executives at RCA Victor Records, which signed the trio in 1959. “Shout,” the group’s first single for RCA, was an original the trio had concocted out of a call-and-response vamp they added to their live cover of Jackie Wilson’s “Lonely Teardrops.”

The electrifying “Shout” joined the ranks of Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode” as a song all fledgling rock ’n’ roll bands needed to play. Their next hit, “Twist and Shout,” was first recorded by the Top Notes, but Bert Berns, who co-wrote the song, disliked the Phil Spector production so he brought the tune to the Isleys, who rearranged it, giving it a gospel makeover echoing the catharsis of “Shout.”

“Twist and Shout” gave the Isleys their first genuine pop hit, but the group struggled to gain traction after the single completed its run on the charts. In 1964, they founded their own imprint called T-Neck — the label’s name derived from their new home of Teaneck, N.J. — and released “Testify,” a single they wrote in hopes of riding the wave created by the Beatles covering “Twist and Shout.” Featuring lead guitar from a young Jimi Hendrix — then billing himself as “Jimmy” — “Testify” didn’t find an audience, so the Isley Brothers called in a favor with Berry Gordy Jr. in 1965, asking to record for his Motown Records. Gordy signed them, and they proceeded to have one of their defining hits with the buoyant “This Old Heart of Mine.” Although they had a few other hits for the label, including “Take Me In Your Arms (Rock Me A Little While),” Motown didn’t prove a good fit for the Isleys, and they left after a couple of years.

The Isley Brothers revived T-Neck in 1969, signing a distribution deal with the bubblegum label Buddha, and released the colorful funk number “It’s Your Thing.” Their first R&B No. 1 and their biggest pop hit, “It’s Your Thing” won the Isleys a Grammy for R&B vocal performance by a duo or group, laying the foundation for the success that came in the 1970s.

The Isleys began to hit their stride with “Givin’ it Back,” a 1971 album that was the first to feature guitarist Ernie Isley, bassist Marvin Isley and Chris Jasper, a keyboardist who was Rudolph’s brother-in-law. This trio of younger musicians pushed their older kin into progressive territory — their covers of Bob Dylan’s “Lay Lady Lay” and Carole King’s “It’s Too Late” lasted longer than 10 minutes each — and the Isley Brothers acknowledged their debt by making all three full band members starting with 1973’s “3+3.”

“3+3” was the cornerstone of the second phase of the Isley Brothers, the beginning of their time as a sextet and the first album to be distributed by the major label Epic. “That Lady” showcased the group’s vibrant makeover, a spangly funk-rock number that found a counterpart in the smooth, glistening reinterpretation of Seals and Crofts’ soft-rock standard “Summer Breeze.” The Isleys spent the next five years creating variations on these two themes, and while only 1975’s righteous “Fight the Power” replicated the pop success of “That Lady,” they routinely reached the R&B Top 10 with such hits as “Live It Up,” “The Pride,” “Take Me to the Next Phase” and “I Wanna Be With You.”

The Isleys’ hot streak began to cool off in the early 1980s. They could still manage a Top 10 hit, like 1983’s seductive “Between the Sheets,” but the friction between the older and younger trios led to the group fracturing in two. Ernie, Marvin, and Chris left to form Isley-Jasper-Isley, while Rudolph, Ronald and O’Kelly carried on as the Isley Brothers, releasing “Masterpiece” on Warner Bros. in 1985.

Not long after the release of “Masterpiece,” O’Kelly died of a heart attack in 1986. Rudolph and Ronald continued as the Isley Brothers, releasing a pair of albums at the end of the 1980s, but Rudolph’s interest in the group waned, and in 1989, he left to become a minister. Ronald brought Ernie and Marvin back into the fold with 1992’s “Tracks of Life,” then kept the Isley Brothers active for the next 30 years.

The Isley Brothers were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1992. The Recording Academy inducted “Shout” into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999; “Twist and Shout” received the same honor in 2010.

In 2004, when BET gave the group a lifetime achievement award, Rudolph reunited with his brothers. It would be the last time they shared a stage together. In March 2023, Rudolph sued Ronald, claiming that his brother registered the trademark for “The Isley Brothers” as an individual, thereby excluding his sibling from his rights in their partnership.

Rudolph Isley is survived by his wife, Elaine Jasper Isley, and their children Elizabeth, Valerie, Elaine and Rudy, along with his grandchildren.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.