Greg Iles almost died writing his latest book: ‘This might be the last thing I ever do’

On the Shelf

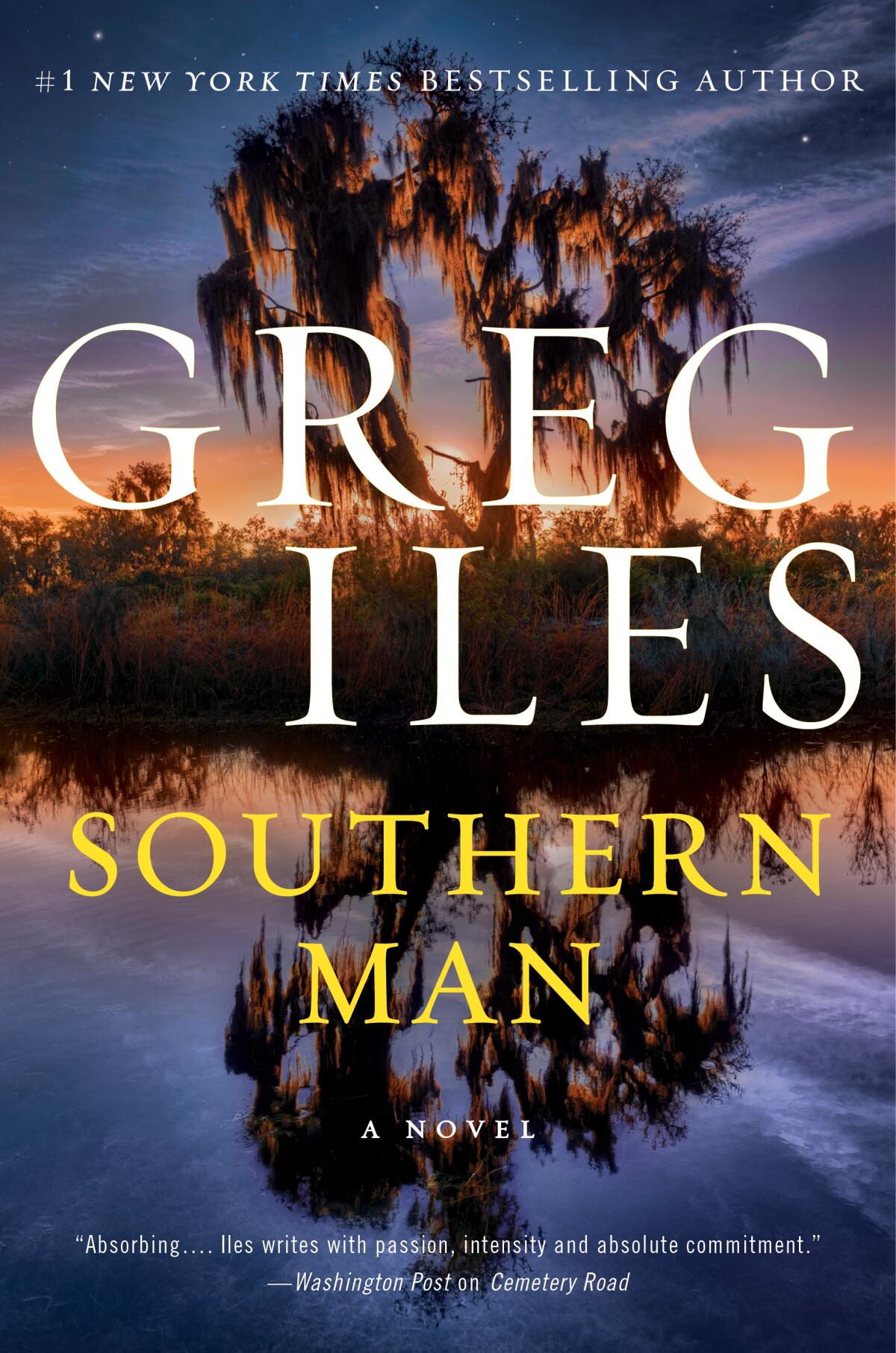

Southern Man

By Greg Iles

William Morrow & Company: 976 pages, $36

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores

Penn Cage leads a dramatic life — he’s a Houston prosecutor turned novelist turned mayor of his hometown of Natchez, Miss.

When his father, a beloved local doctor, was charged with murdering his former nurse — who was his long-ago lover — and went on the run, Cage dug for the truth, finding links to 1960s lynchings by a vicious KKK offshoot and to contemporary corruption and racism. Cage ultimately went outside the law to destroy the criminals; his fiancée and others were killed along the way.

More recently, while Cage was living in nearby Bienville, his daughter was shot and wounded during a rap concert and soon after, the mayor, who was Black, gay and relatively progressive, was murdered in cold blood. As racial tensions consumed the town, an ambitious war hero turned radio host named Robert E. Lee White caught Cage’s attention as he tried to capitalize on the chaotic situation. Again, Cage survived shootouts and broke the law for the sake of justice.

Cage’s saga exists only in Greg Iles’ bestselling books, most famously his 2,300-page “Natchez Burning” trilogy and now his latest, “Southern Man,” which runs nearly a thousand pages itself. They’re thrillers with the stakes raised by Iles’ exploration of the racism that has long ruled the South and haunted the nation.

But Iles’ own life story is novel-worthy. It’s an epic with twists and turns and his own brushes with death.

After nearly a decade playing guitar in the band Frankly Scarlet, Iles turned to fiction, finding success in the 1990s with a pair of World War II thrillers. Then, at 36, a routine exam left him staring death in the face. He had myeloma, at the time a “rapid death sentence,” he explained in a video interview from his Natchez home.

Iles was asymptomatic and the rare patient for whom the disease “smoldered” for decades. Living with the disease and keeping it secret to protect his career “was like walking in permanent shadow, with the hawk of mortality hovering over your shoulder day and night.”

He turned down opportunities, prioritizing for his family the financial security of his proven career. “The cancer affected every decision I made,” he says. “I wrote more commercial books than I would have and wrote much faster than I might have otherwise.”

Author Chris Bohjalian discusses his 25th novel, ‘The Princess of Las Vegas,’ and how ancestral trauma from his Armenian heritage contributes to the dread in his work.

Iles’ life changed again during “Natchez Burning.”

He’d written about Natchez in “The Quiet Game” in 1999, but looked back with “regrets,” having fallen victim to the nostalgic blinders of many white Southern writers. “I’m embarrassed by my view of the world then,” he confesses.

Reading the investigative journalism of Stanley Nelson, editor of the Concordia Sentinel in nearby Ferriday, La., Iles learned about the lynchings that happened in and around Natchez in the 1960s.

Nelson drove Iles around the region, sharing research and stories. “Greg took the issues and did a masterful job of exploring attitudes about race in his fiction with characters that can emotionally draw people in and get them to understand,” said Nelson, who was immortalized as reporter Henry Sexton in “Natchez Burning.”

Indeed, Iles says he uses his genre skills for a cause. “I’m writing for a white audience about a subject most would prefer not to think about but they can be seduced into reading a thriller,” he says.

Scott Turow, who became friends with Iles while performing in the Rock Bottom Remainders, their band that also features authors including Dave Barry, Amy Tan and Stephen King, says Iles reminds him of King for “his ability to turn serious matter into popular fiction.”

Don Winslow reveals why his latest novel, ‘City in Ruins,’ the final installment in the Danny Ryan series, will be his last.

The frankness and intensity in Iles’ books are essential to his personality too, Turow adds. Iles is charming and affable, a natural storyteller with a reflective side. But he grows impassioned while recounting the creation of the trilogy.

The more he learned about those real-life cold cases and the surviving killers, the more he wrote. Finally, he told his publisher this story needed three books. The answer was no. One day in 2011, Iles was driving while contemplating this conundrum.

Then everything went black.

After eight days in a medically induced coma, Iles awoke to learn a truck had hit his car. “I was missing my right leg below the knee, had a patched aorta and more broken bones than I can remember.”

This brush with mortality — a year after the death of his father, who was a doctor whom he admired greatly — made Iles determined to honor his personal vision. He again told his publisher he needed a trilogy, period.

The publishing house walked away, leaving him with “frightening” debt. He soon landed a new deal with HarperCollins and wrote relentlessly while recovering. When “in the flow,” Iles writes for 16, 24 or even 30-hour stretches. While going hard and fast, he also is “granular,” blending historical facts, people and places with fictional ones.

His instincts were spot on. The three books, released in 2014, 2015 and 2017, climbed bestseller lists. Still, he says, there was always backlash from some white readers. He expects even more for “Southern Man,” which was fueled by his outrage at the “the animus that Donald Trump released.”

He was so angry that the first draft of “Southern Man” was “virtually unreadable.” Upon stumbling on King’s “The Dead Zone” on TV, he had an epiphany: his novel needed a character like King’s Greg Stillson, a dangerously populist politician. So Iles introduced Robert E. Lee White as a “dark mirror of Penn Cage,” a conservative, but pro-choice and anti-Trump, third-party candidate for 2024.

Here are 20 upcoming books — publishing between late May and August — that we recommend to kick off the summer reading season.

White is more complex than Iles’ earlier antagonists, unnervingly confident in his own vision and in his belief that he can manipulate the public and boost his campaign without losing control of events.

But as Iles resumed writing, a new bombshell landed. The myeloma had “switched on” and his future was suddenly and immediately imperiled. Although his mother had just died in October 2020 from the same cancer, science had progressed tremendously since his original diagnosis, and he immediately began chemotherapy en route to a stem cell transplant.

Unsurprisingly, he couldn’t stop writing. “I couldn’t bear to go into such serious treatment and possibly never finish,” he admits. Chemotherapy kept him alive as he completed the novel and prepared for the stem cell treatment. Thinking he’d be done within two months, he says, “I worked harder than ever before.”

Instead, the book took two more years. That’s partly because writing Iles-style — those 20-hour marathons — during chemo nearly killed him. “I was hospitalized three separate times for extensive periods,” he says, and constantly battled chemo “brain fog.”

The process, and the book, ran so long because Iles understood “this might be the last thing I ever do” and because he saw America as equally endangered, he wanted to commit everything on his mind to the page.

Iles poured more of himself into Cage: his protagonist lost part of a leg in a similar car wreck and was now battling myeloma. In real life, treatment has left Iles diabetic and 40 pounds overweight. His chemo stopped working but his doctor found a successful new drug combination and he’s awaiting a stem cell transplant. “I’m hopeful and optimistic,” he says.

‘Blood at the Root,’ LaDarrion Williams’ first novel in a three-book deal — a series that centers on a Black boy in a YA fantasy saga — is the kind of fiction he wishes existed when he was a kid.

His optimism doesn’t extend to American society. While writing he realized many white Americans only want the democracy they grew up with, “where they sat atop the pyramid,” he says. “Otherwise, they’ll exchange democracy for autocracy in a flash.”

He worries that, as in the novel, white fear and panic puts us “on a ticking clock to real violence between now and November.”

Iles hopes the novel helps people move beyond William Faulkner’s notion that “the past is never dead.” “It’s incumbent upon us to outgrow and to transcend the past,” he says.

In “Southern Man” he gives Black characters more “page time.” The trilogy lacked significant Black characters until the third book, in part because he was focused on prying open white readers’ eyes but also because “I knew I had nothing to teach Black readers” about racism.

He remains wary of presuming to write from a Black person’s perspective, but “Southern Man” has three Black characters playing crucial roles; they even call out Cage on the limits of his understanding and allyship. He hopes their addition helps shape readers’ reactions.

“If I can make white readers see America — even a little bit — through a Black character’s eyes, we have a better chance of finding common ground,” Iles says.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.