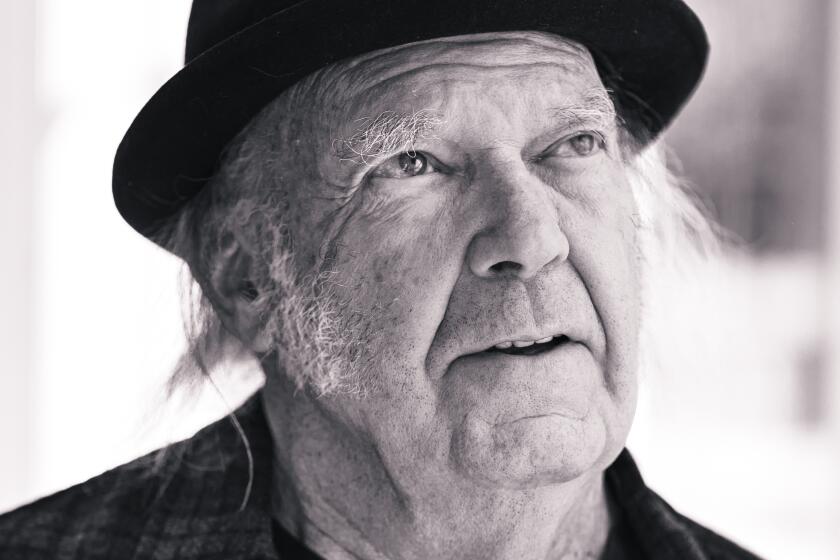

The nightclub is mostly empty as Lou Adler slides into a booth at the Roxy Theatre, the iconic music venue he co-founded half a century ago on the Sunset Strip. The stage will be dark tonight, but Adler looks pleased just to be here at age 89, his beard white and full, ready to talk about the decades of musical history that have unfolded at the club.

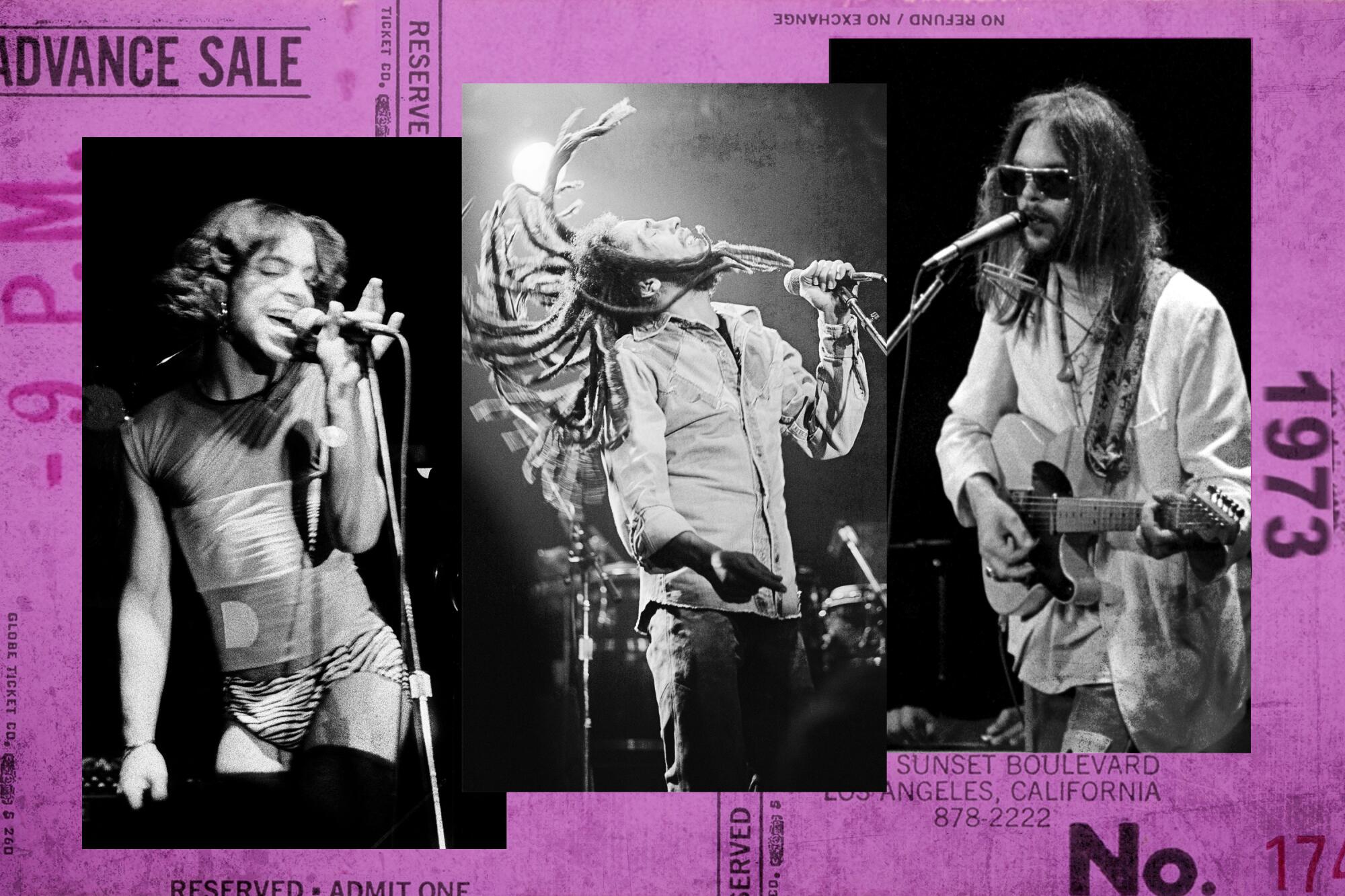

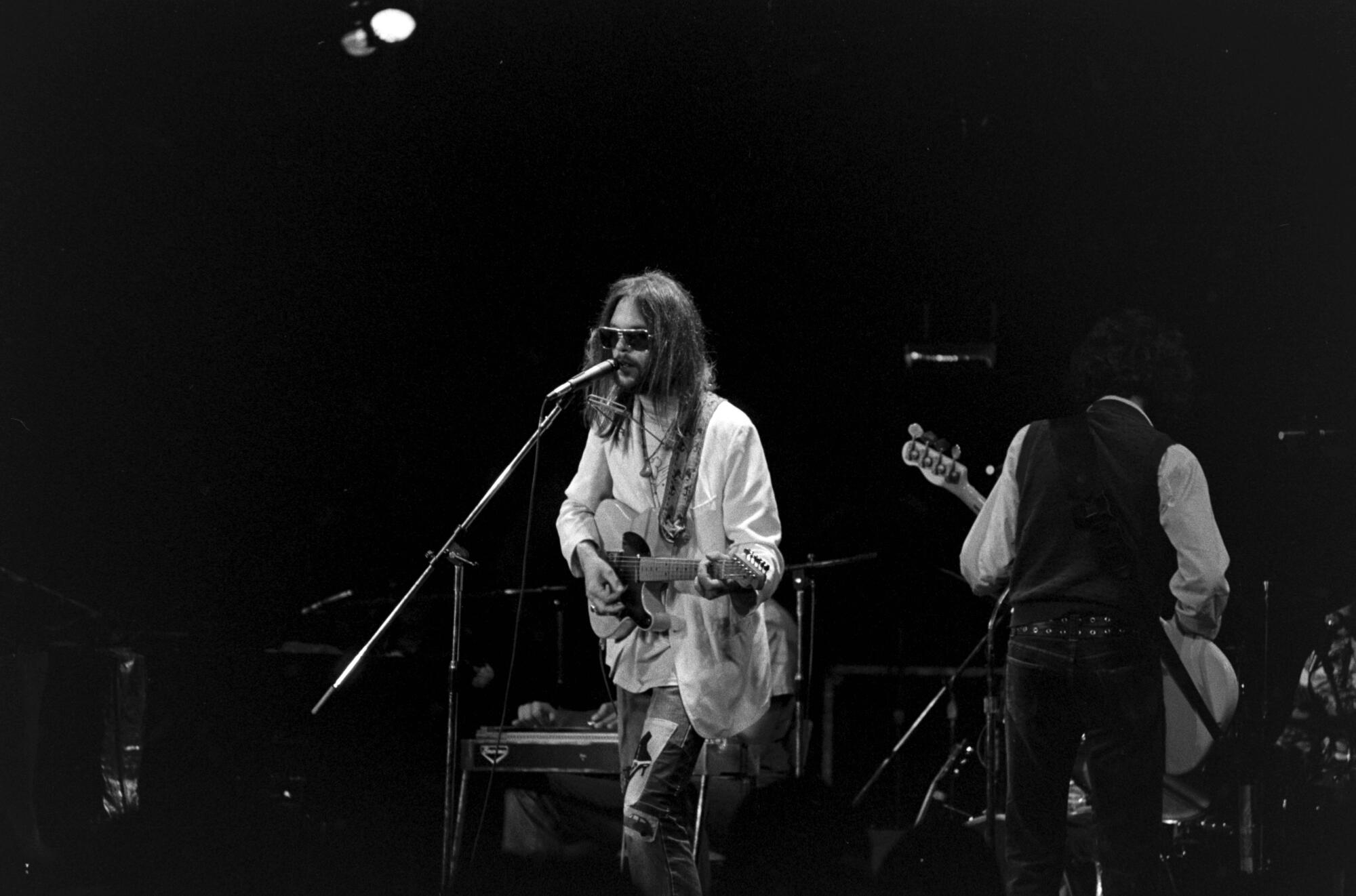

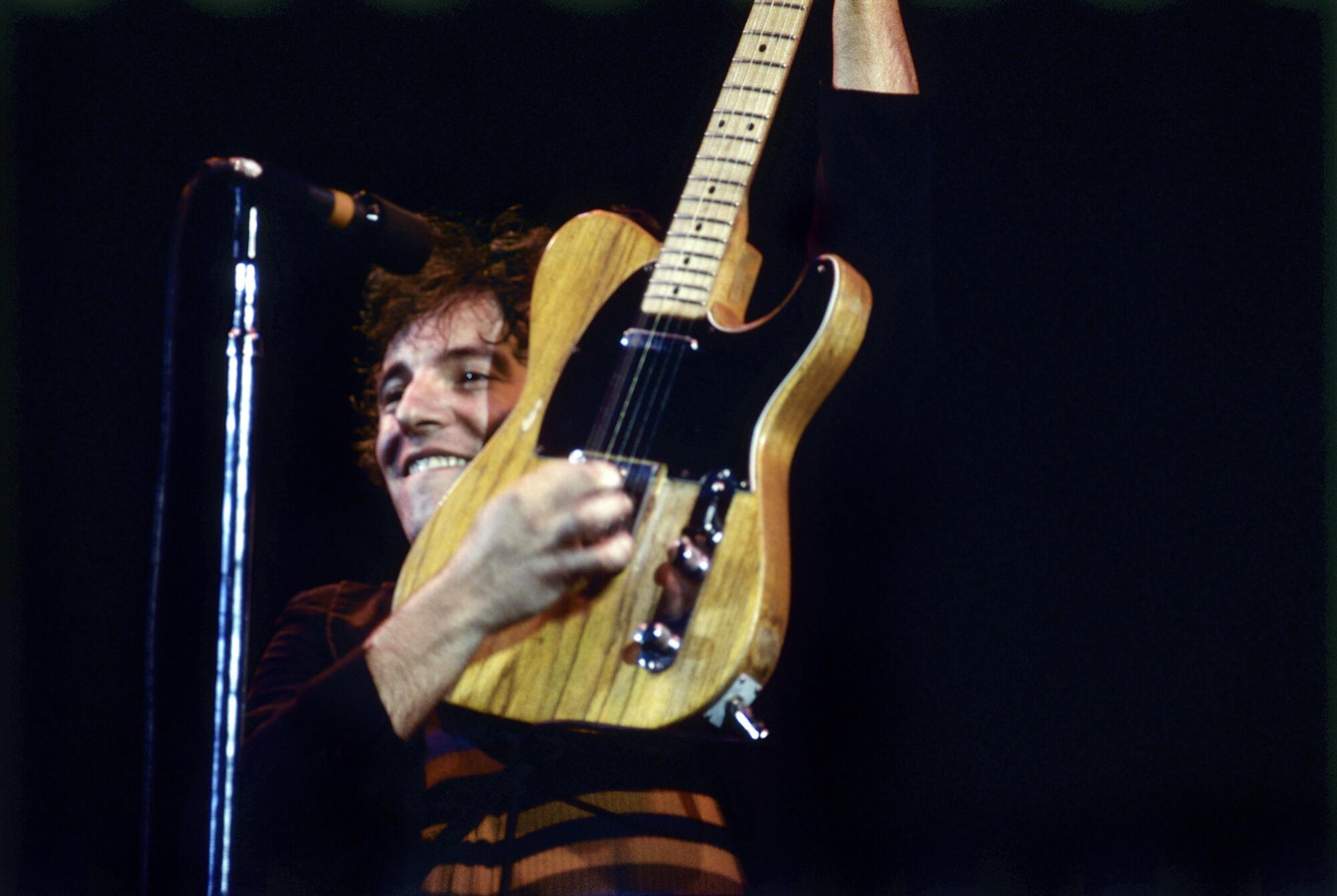

There’s been a lot of it, starting with Neil Young opening the Roxy with three nights of shows in September 1973 and a subsequent roll call of superstars and icons ever since, from Bruce Springsteen to Bob Marley, Linda Ronstadt to the Clash, Lou Reed to Prince, Slayer to Jay-Z.

Beloved nightclubs come and go, but the Roxy has few peers in L.A. or elsewhere, both a hallowed venue where rock gods minted their legends and a still-thriving venue at the heart of the city’s musical nightlife.

“At this point in my life, numbers always surprise me. My own age surprises me,” Adler says with a smile, dressed in color-coordinated shades of orange and brown, including a pair of futuristic designer Crocs. “I certainly have pride in the fact that we’re sitting here talking about something that we opened 50 years ago.”

That history will be the focus of a series of Roxy50 honors and events this fall, including a return engagement by Young to the 500-capacity nightclub on Sept. 20. Beginning Sept. 15, the Grammy Museum will host an exhibit of photographs documenting famous performers at the club and other artifacts, plus the small cabaret piano that was once upstairs at the Roxy’s private club, On the Rox. The West Hollywood Library will host an exhibit of photographs, and Adler is being awarded a key to West Hollywood.

“When Guns N’ Roses was starting out, that was the place we aspired to,” says Slash, the band’s lead guitarist, describing their rise on the L.A. club circuit that included gigs at the Whisky, the Troubadour and the now-defunct Starwood. “Because Lou Adler was such a name, and he attracted a high-profile clientele, it established a certain kind of glamour that the other clubs didn’t really have. It’s held up to this day.”

With the release of his new Rick Rubin-produced album, ‘World Record,’ Young talks the climate crisis, boycotting Spotify and the 50th anniversary of ‘Harvest.’

At one time, opening the Roxy might have seemed a surprising side hustle for Adler. Before the Roxy, he was a co-founder of the groundbreaking Monterey International Pop Festival in 1967 and had enjoyed huge success as a talent manager, record-label owner and the producer of hits by Carole King and the Mamas & the Papas.

And yet the Roxy soon became a second home and a permanent part of his life.

The idea was to create a “1940s nightclub” for rock, he says now, with excellent sound and sightlines and respect for artists and fans. It was partly inspired by some rude treatment Adler had received at the nearby Troubadour, where King was making her first appearance as a solo artist. Adler was King’s manager and producer, and she was signed to his label, Ode Records. “You’re not on the list,” he was told twice by a Troubadour doorman and given the brush-off.

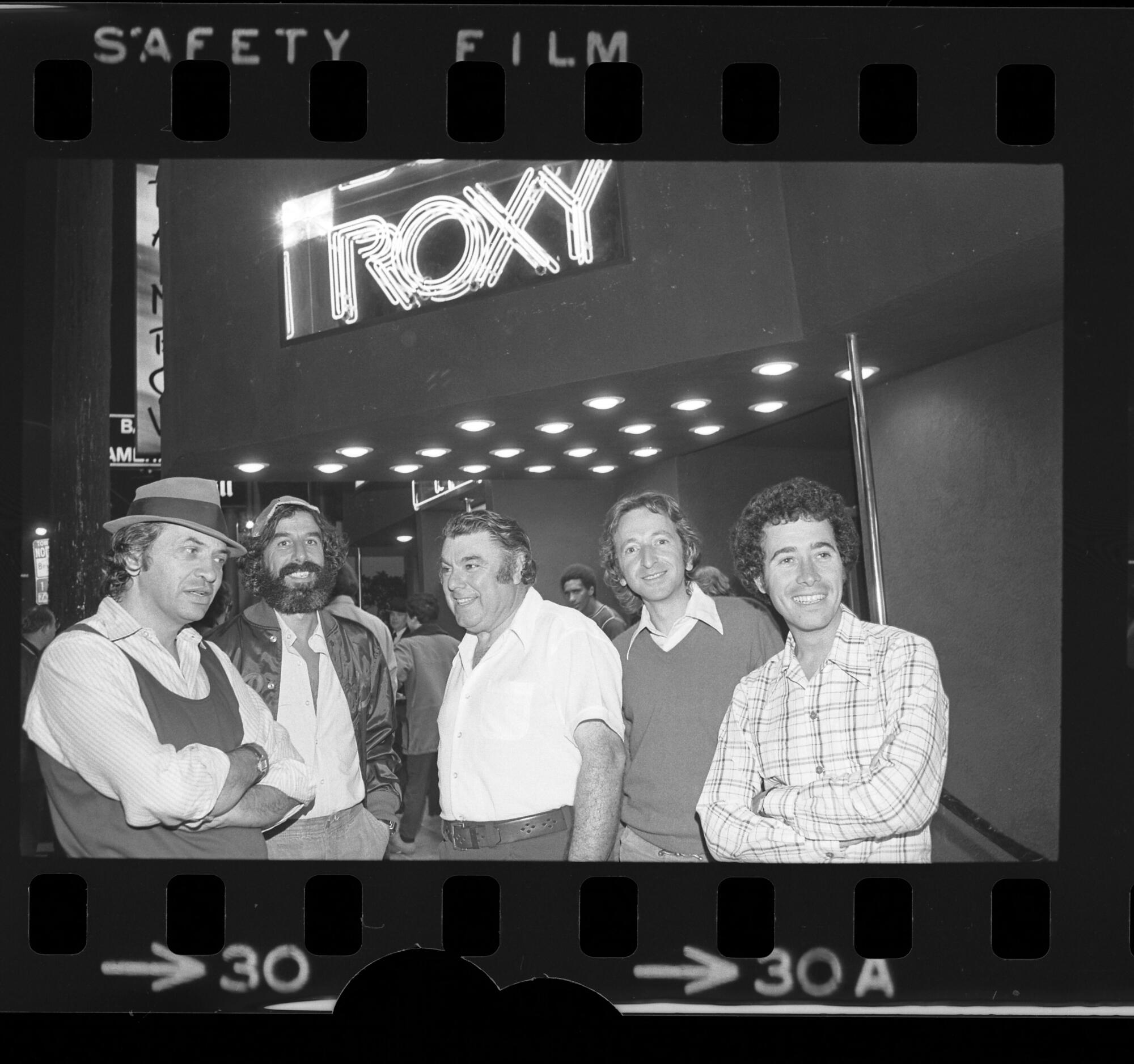

He relayed the incident to his friend Elmer Valentine, who founded the Whisky a Go Go in 1964. They were already partners (along with Mario Maglieri) in the Rainbow Bar & Grill and decided the Strip needed another rock club. Conveniently, next door to the Rainbow was a strip club called Largo, boasting “the biggest burlesque floor show in the U.S.A.,” which they took over and renamed the Roxy Theatre to evoke a vintage nightclub.

In addition to Valentine, Adler gathered a dream team of music-world impresarios as owner-investor-advisers in the Roxy “to validate it before we ever opened,” he says. That group included San Francisco-based rock promoter Bill Graham; Elliot Roberts, who managed Young and Joni Mitchell and co-founded Asylum Records; David Geffen, fast-rising manager and label executive-owner; and manager-record producer Peter Asher, who worked with James Taylor and Linda Ronstadt. Chuck Landis, who ran the Largo, was also part of the group.

“It was a high-powered team,” Asher says now.

On Sept. 20, 1973, fans lined up along the Strip as Young headlined the first of several shows with support from Graham Nash and the comedy duo Cheech & Chong. Young performed songs almost exclusively from what would become his wounded and ragged “Tonight’s the Night” album. Between songs, the rocker noted the room’s previous entertainers: “They say Candy Barr used to dance right here on this stage.”

That November, Ronstadt played a few nights at the Roxy and invited her friend Emmylou Harris to join her onstage. At the time, Harris was best known as the singing partner of Gram Parsons, who had just died of a drug overdose in Joshua Tree.

“Emmylou had just lost Gram Parsons, and she was feeling pretty sad,” Ronstadt says now by telephone. “And I said, ‘Why don’t you come out and we’ll do some singing?’ So she came out and she brought the cowgirl outfit, brought one for me. I was really thrilled to be able to sing with her.” Among the songs they performed together was a cover of Dee Dee Warwick’s “You’re No Good,” soon to be a No. 1 hit for Ronstadt.

During those first months, the club hosted famed artists including Jackson Browne, the Temptations, Frank Zappa and Genesis. But its life as a nightclub was about to be interrupted.

From intimate clubs to picturesque outdoor theaters to state-of-the-art arenas and stadiums, there’s no better place to see live music than SoCal.

During a 1973 trip to London, Adler took in a subversive hit stage musical called “The Rocky Horror Show” and within two days signed a deal to bring it to the Roxy for its U.S. premiere. Fueled by ‘50s-style rock ’n’ roll and the era’s exploding glam-rock movement, the production was an outré sci-fi horror satire swirling around a cross-dressing scientist in fishnets and sparkling heels called Dr. Frank-N-Furter, played by a wildly charismatic Tim Curry.

The actor made his nightly entrance at the Roxy from the lobby to the stage, belting out the signature tune “Sweet Transvestite.” “Tim’s entrance was phenomenal,” recounts David Foster, the Grammy-winning composer and producer, who early in his career was the show’s pianist. “The place just went berserk because, of course, he was so much bigger than life.”

Photographs from opening night reveal a star-studded scene, with John Lennon, Mick Jagger and Cher in the crowd. Adler stood smiling in a satin jacket beside longtime friend Jack Nicholson, dressed like Jake Gittes from the soon-to-be-released “Chinatown.”

After a year of “Rocky Horror” performances, the Roxy turned back to live rock and soul. Among the more electrifying concerts was a series of shows by Bob Marley and the Wailers.

“That was one of the best shows I’ve ever seen,” Ronstadt says. “To see something that authentic and that close to the root, and with that caliber musician. We’d all been listening to the records, but there it was right in front of us. And there was nothing that could replace that.”

Upstairs from the Roxy, with its own entrance on Sunset, was On the Rox.

“It was that Vegas thing: What happened there stayed there,” says Adler, whose famous friends became regulars, along with a rotating crowd of stars from music, Hollywood and, later, sports. Asher remembers the club in those first years as a blur of “hot women and drugs — a reliable combination, I suppose.”

For Cheech & Chong, the Roxy became a location for the filming of their first movie, “Up in Smoke,” directed by Adler. The scene involved the comedy duo engaged with a battle of the bands in front of a rowdy crowd.

“It was our home territory,” Cheech Marin says now. Adler discovered the duo during a performance at the Troubadour, signed them to his label and produced a series of popular albums that led to a movie career. “He’s a spotter of talent,” Marin says of Adler. “He can see something that’s new and, more importantly, he knows how to promote it.”

In 1978, Todd Rundgren performed a week of concerts, two shows a night, at the Roxy. He was joined by an all-star cast of guests, including Stevie Nicks, Hall & Oates and Rick Derringer. Rundgren recorded the shows and included several tracks on his live compilation, “Back to the Bars.”

One night, he says, a fan gave him a purebred lhasa apso puppy. Another fan gifted him an exotic bird. He kept the dog. “We couldn’t figure out how to get the bird home,” Rundgren says. “Somebody else wound up with the bird.”

Punk rock arrived later that decade, represented at the club first by New York City acts like Patti Smith and Television. If the Roxy didn’t immediately embrace the homegrown punk-rock scene, it soon became an essential venue for leading lights from its first wave, hosting shows by the Screamers and the Germs, which were graduating from underground clubs like the Masque.

X hosted four nights celebrating the 1981 release of “Wild Gift,” the band’s acclaimed sophomore album, decorating the stage with garlands of fake flowers.

Singer-bassist John Doe compares the Roxy to other favorite venues across the country, including the Fillmore in San Francisco and Irving Plaza in New York, though the Roxy is smaller in size. “It’s big enough so that it doesn’t feel like a small club, but it is,” Doe says.

In 1995, a new band called System of a Down played its very first show at the Roxy and quickly made the club an early home for its frantic, metal-folk eruptions. System became a platinum-selling band and ultimately moved on to bigger rooms, but singer Serj Tankian fondly recalls the Roxy and Adler. “I’ve seen some club owners that are total jerks, act horribly with bands and denigrate all their employees and the artists,” he says. “Not at the Roxy.”

As time rolled on, Adler began stepping back from running the club. His oldest son, Nic, started to manage things on-site, as Adler pursued his growing obsession with attending Lakers games at the Forum, where he could usually be found courtside with Nicholson. “I just changed my stage,” Adler says.

On Wednesday, Drake became the latest artist to get hit by an object hurled by a fan at a concert. Should we blame the pandemic? Social media? Lazy bouncers?

The Roxy remains a family business, and three more of his sons have become involved. Booking is now handled by Goldenvoice Productions, which Adler first encountered as a street-level company promoting punk, metal and goth shows in Southern California. It is now the force behind the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, a kind of latter-day manifestation of Adler’s Monterey Pop Festival.

Adler attends Coachella every year, and he’s grown close with Goldenvoice President Paul Tollett. “Paul’s part of the family,” Adler says.

Two decades ago, Adler bought the land underneath the Roxy to protect the club’s future. As other popular clubs in Southern California were absorbed by Live Nation in recent years and overtures to the Roxy were made by the company, Adler says he was determined to keep it in the family.

“Pretty soon, it becomes a numbers game, and it’s run for somebody that doesn’t come in contact with those people every night,” Adler says of the club and its clientele. “You’ve gotta have a feel — Elmer called it a ‘face.’ There’s got to be a face that they know.”

The club is still going strong, hosting established acts and rising new voices like Blondshell on Aug. 2. The Roxy has survived the COVID-19 pandemic and dramatic changes on the Strip. The bulldozers that swept away the House of Blues now threaten the Viper Room, but not the Roxy.

“Oh, I think we’ll be here forever. It may turn into a building that houses the Roxy and has apartments,” Adler says. “Whatever’s going to happen to Sunset Boulevard we’ll sort of go along with it, as long as there’s always a Rainbow, a Whisky and a Roxy.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.