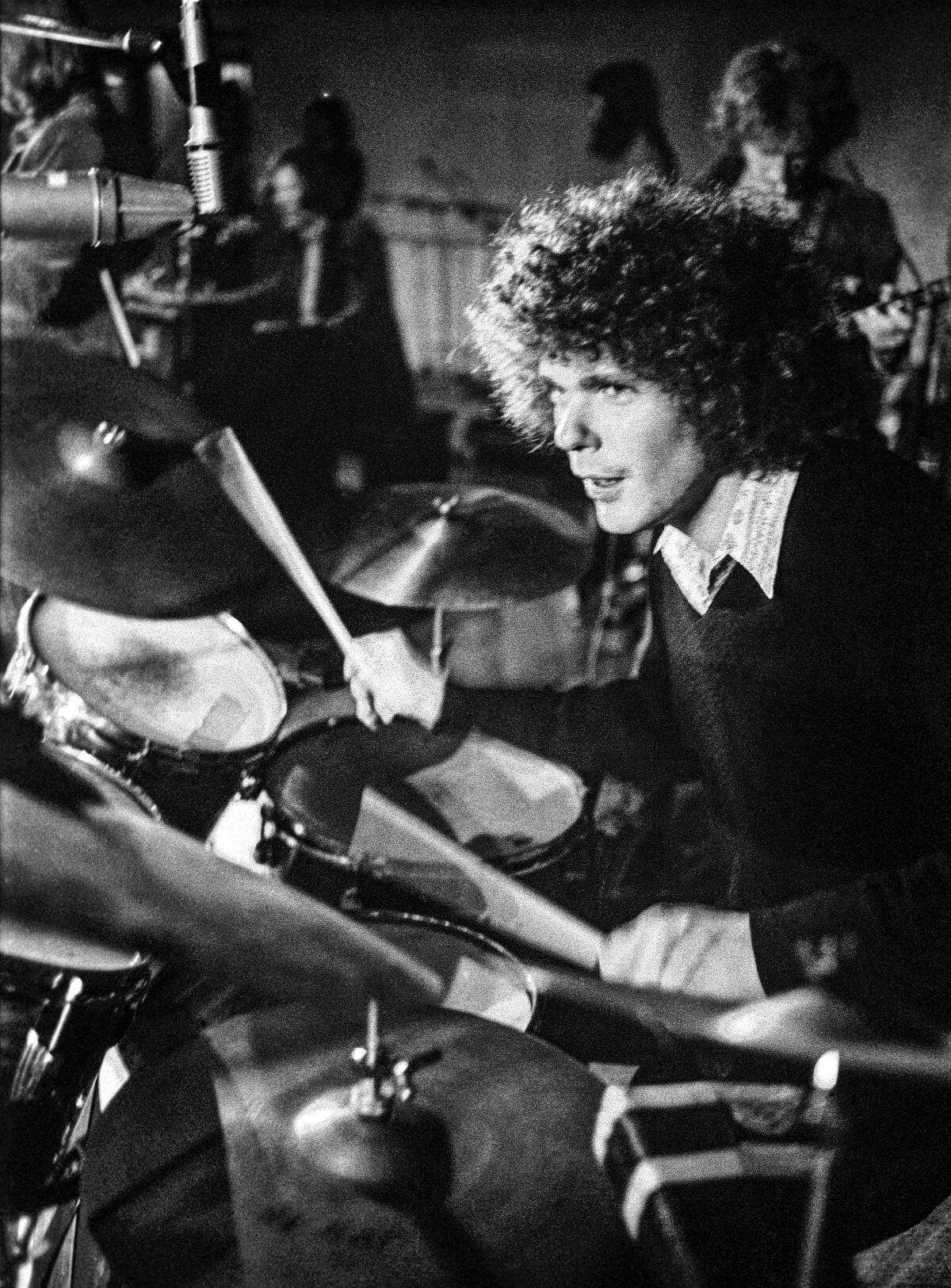

Jim Gordon, famed session drummer convicted of murdering his mother, dies at 77

Jim Gordon, the prolific session drummer who played with some of rock’s biggest stars — including the Beach Boys, several Beatles and Eric Clapton, whose classic “Layla” he’s credited with co-writing — before he was sentenced to prison for killing his mother, died Monday at the state-run California Medical Facility in Vacaville. He was 77.

His death was confirmed by a publicist, Bob Merlis, who said Gordon died of natural causes “after a long incarceration and lifelong battle with mental illness.”

A Los Angeles native, Gordon was a member of the so-called Wrecking Crew of studio musicians who shaped the sound of countless pop hits in the late 1960s. Among the records he appeared on were Glen Campbell’s “Gentle on My Mind,” Mason Williams’ “Classical Gas” and the Beach Boys’ influential “Pet Sounds” LP. In the ’70s, he played on Carly Simon’s “You’re So Vain,” a No. 1 hit on Billboard’s Hot 100; Albert Hammond’s “It Never Rains in Southern California”; and “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number” by Steely Dan, in addition to songs and albums by John Lennon, Harry Nilsson, Traffic, Van Dyke Parks, Seals & Crofts, Art Garfunkel and many others.

Gordon’s drum break on the Incredible Bongo Band’s rendition of “Apache” from 1973 became a foundational hip-hop sample used in more than 750 songs, according to the website WhoSampled, including tracks by the Sugarhill Gang, MC Hammer, L.L. Cool J, Busta Rhymes, the Wu-Tang Clan and Nas.

“Clapton always praised Jim for what he called ‘the big fill,’” said veteran rock critic Joel Selvin, whose biography of Gordon is due to be published next year. “And Ringo Starr thought he was the greatest rock drummer ever. It wasn’t just his surgical skill and his extraordinarily developed technique but this intuitive element that elevated his drum part on every record he played on.”

On the eve of ‘Songs of Surrender,’ featuring new takes on old classics, the singer and guitarist talk about reinventing their songbook and their future as a foursome.

James Beck Gordon was born July 14, 1945, and grew up in Sherman Oaks; his father was an accountant and his mother a nurse. After learning to play drums in high school, he got a gig at age 17 — “with the help of a fake ID,” according to a 1994 profile in the Washington Post — backing the Everly Brothers on tour in England. Later, his session work led to a job with Delaney & Bonnie, the soul-rock outfit whose guitarist at the time was Clapton; Gordon and Clapton went on to form Derek and the Dominos, who were first heard playing behind George Harrison on his 1970 triple album “All Things Must Pass.”

Derek and the Dominos released one studio album, “Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs,” in 1970; its seven-minute title track, which was inspired by Clapton’s infatuation with Harrison’s then-wife Pattie Boyd, made the top 10 of both the American and British singles charts. Gordon also toured in the early ’70s as a member of Joe Cocker’s famed Mad Dogs & Englishmen band, during which he was in a relationship with singer Rita Coolidge, who wrote in her 2016 memoir that Gordon physically abused her. (Gordon is also widely thought to have taken credit for Coolidge’s contribution to “Layla.”)

In 1983, Gordon — known by then to friends and family for being “tormented,” as the Post put it, by voices in his head — killed his mother, Osa Marie Gordon, bludgeoning her with a hammer before stabbing her with a butcher knife.

“When I remember the crime, it’s kind of like a dream,” he told the Post. “I can remember going through what happened in that space and time, and it seems kind of detached, like I was going through it on some other plane. It didn’t seem real.”

Gordon, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia, was sentenced in 1984 to 16 years to life in prison. He was denied parole several times.

He is survived by his daughter, Amy, from his first of two marriages.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.