‘We have all quiet quit U2 over the years’: A conversation with Bono and the Edge

“I’ve written a book with a title I’ve yet to fathom or properly grasp,” U2 singer Bono inscribed on the title page in my copy of his recent memoir, “Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story.” U2’s long, blockbuster career — 14 studio albums that have sold 170 million copies worldwide, plus 22 Grammys — is rooted in a similar quixotic ideal of trying to fathom big topics like love, faith and community.

From their origins as a guileless, almost emo Irish post-punk band to their mulleted mainstream success in the late ’80s through their subsequent decades as stalwart rock elders who can sell out stadiums, they’ve asked questions of us and themselves, then rejected the answers in favor of more questions. They’ve never settled for big when they could aim for huge and epic.

Bono’s memoir also inspired a new album, “Songs of Surrender,” to be released on Friday, on which U2 — Bono, guitarist the Edge, bassist Adam Clayton and drummer Larry Mullen Jr. — revisit 40 of their previous songs, as far back as their debut album, and not only strip down the arrangements, but in several cases revise the lyrics as well.

In separate Zoom interviews — Bono, 62, from his Los Angeles hotel and the Edge, 61, from his Malibu home — some personality differences were obvious. The guitarist, in a gray hoodie and his ever-present beanie, spoke prosaically and held his cards close to the vest. The singer, in a black T-shirt and his ever-present circular purple sunglasses, spoke floridly, often poking fun at himself and his bandmates, and leaned in close to the camera when he got excited — which is his characteristic state. (Shortly after the interview, he Fed Ex’ed me the signed copy of his memoir, unprompted.)

Our topics included the arrogance of great songwriting, Bono’s new uncharacteristic vocal style and whether Mullen is “quiet quitting” U2.

The simpler arrangements on “Songs of Surrender” reminded me of MTV’s “Unplugged” series. Does an “Unplugged” analogy seem accurate to you?

Bono: Yeah it does, although we made a point of including some songs that weren’t unplugged. The overarching theme is intimacy, and the way to achieve it was mostly through acoustic instruments. If we were to strip songs down to just voice and guitar, or voice and piano, we’d find out if the emperor was wearing any clothes. We’d at least see what the naked self looks like. Songwriting wasn’t our preoccupation when the Edge and I were younger.

What was your preoccupation?

Bono: The impact, the sonic blast, the feelings, and staking our claim on new territory, emotionally and musically. We were that obnoxiously inclined.

With Adam and Larry more in the background on “Songs of Surrender,” is this U2 reinterpreting U2 songs, or is it Bono and the Edge reinterpreting U2 songs?

Edge: Ooh, a very good question. Adam and Larry’s contributions were not as big because we were trying to come up with the minimum arrangement we could get away with. Everyone’s personality is there, and also the songs are U2 songs — so of course it’s a U2 album.

Bono: They didn’t need to play on all the songs, because then we’d be just a rock band.

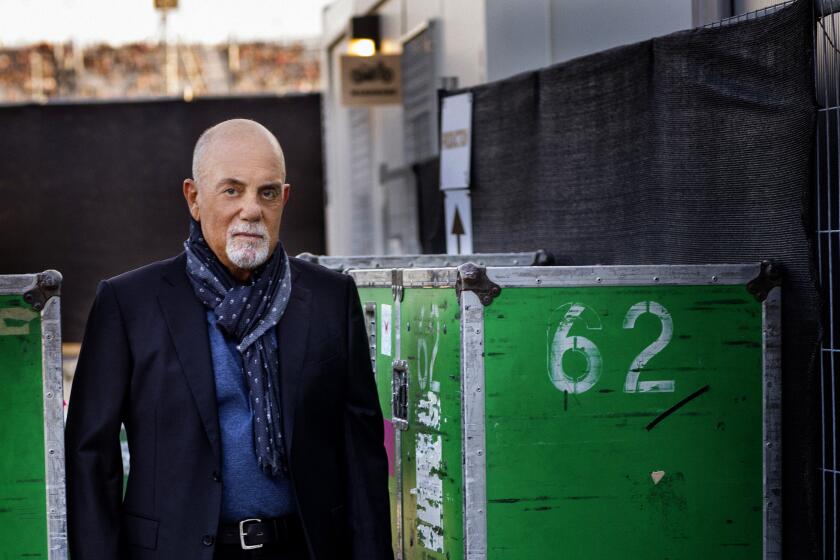

Joel, who performs with Stevie Nicks on Friday at SoFi Stadium, on the inspiration for ‘Piano Man,’ farewell tours and his ‘70s hit he now calls ‘dreary.’

These songs mean a lot to a lot of people. Why change them?

Edge: We didn’t go out of our way to change them, as such. In the case of, say, “Stories for Boys,” it was written when we were boys, and it explains what we were going through. It’s hard for a 60-year-old man to make those lyrics believable, so we rewrote the song. It’s got a pathos now, where the original version had exuberance and bravado.

One of the new lyrics in “Stories for Boys” is, “In my imagination, there’s only static and flow/No yes or no” instead of, “Sometimes a hero takes me/Sometimes I don’t let go.” What does the change signify?

Edge: That’s about self-acceptance. At the time of our first album, we were, like most kids, self-doubting and self-critical. We were inspired by “Lord of the Flies” and by a beautiful movie called “If.” The new lyric acknowledges that we were way too hard on ourselves. It’s a little pat on the head.

Once you decided to reinterpret the songs, how did the process start?

Edge: Mostly the tracks started with me. I’d make a simple outline — what’s the key, what’s the tempo, add some acoustic guitar or piano. When Bono started singing, we knew instantly if it was working.

Bono sounds much more sedate and understated on these versions.

Edge: U2 songs quite famously have an emotional connection. The new versions often got too drenched, too sentimental, so Bono quite consciously kept his singing a little more deadpan than normal. With “Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For,” we reined it in so much, it’s almost like a Johnny Cash country song.

Bono, when you revisited those older lyrics, what did you think of the young man who wrote them?

Bono: I have been a little red-faced at the outpouring [of emotions]. I’ve had phases of embarrassment, but I’m out the other side of it now. That’s the job of our music presently: Can we be as barefaced, as defiant, as vulnerable as we used to be? Can we be as uncool?

Edge: We were aware, back then, of being way too open-hearted.

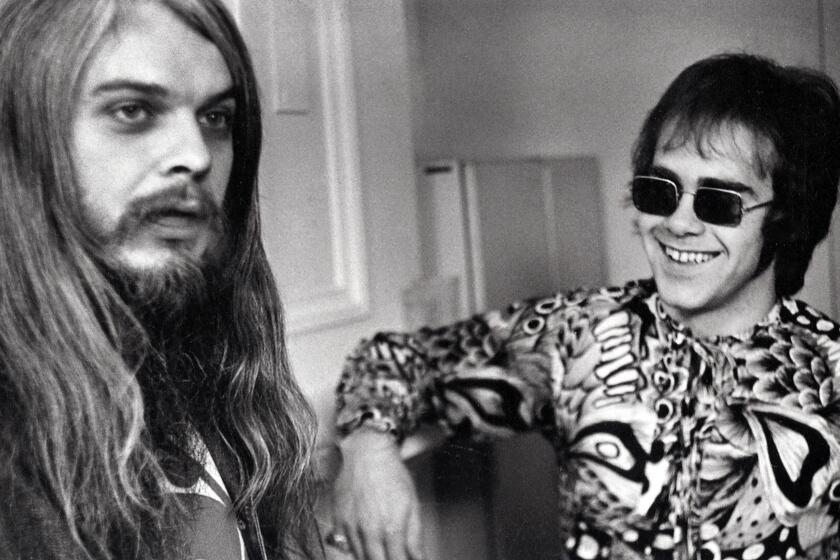

In “Leon Russell,” Bill Janovitz tracks a rocker who played with Jagger and Dylan, turned Willie Nelson into a hippie, made six gold records and faded away.

U2 started out as a post-punk band, a style that’s inherently “cool,” in the Marshall McLuhan sense of classifying media, but you flipped it around and made it “hot,” right?

Edge: That might be the Irish influence. There was always a kind of opera, and an emotional intensity to our work.

We met [U2 producer] Brian Eno in the mid-’80s, after he worked with David Bowie and then Talking Heads, who definitely were on the cool side of media. Eno said to us, “It would be a mistake for you guys to try and be cool, because what you are is hot and passionate.” At the time, we did want to be a bit cool.

Bono: I remember Eno saying, “What’s unique about your music is that a lot of it is not influenced by Black music.” And we’d say, “Large swaths of it are, Brian.” He’d say, “No. Small swaths of it are. And that’s the least interesting thing about you, anyway.” (laughs) That was the end of the argument. He’d point to “Pride (in the Name of Love),” “The Unforgettable Fire” or “Beautiful Day” and say, “You own that. That’s your territory.”

So is being uncool part of what characterizes U2?

Bono: Our first album is really an ode to innocence, whereas if you’re in a band, you’re usually trying to deface your innocence. It’s sex in the back seat of a Cadillac. Here’s these Irish teenagers saying, no, we want to hold on to our innocence. I’m amazed at how audacious that was.

I’m a huge U2 fan. I saw one of your first six or so American shows and most of the tours since then. But a few years ago, to be blunt, I realized I was losing interest in U2, as well as some other artists. It dawned on me what those artists had in common: straight white men who were bellowing their emotions. Was there any similar impulse for you, that led to the more sedate approach on “Songs of Surrender?”

Bono: I wish I had the courage and phraseology to say exactly that. We have an internal parlance within the band: “Hello, I’m having a feeling.” It’s one of our descriptions of our music. (laughs) I think it’s OK to ask the question, “Do I need any more of that? Haven’t I felt that from you before?” If you have, I could argue, change the channel as fast as you did. We can take the punches, so throw them any time.

On our last two studio albums, I wanted to go back to first principles: “Don’t bore us, get us to the chorus.” I was tiring of our songwriting. Rock had gotten so unambitious. The Beatles never thought like that! They wanted the whole world: melodies, words, those revelatory moments. They were generous.

But you’re right to be hard on singer-songwriters, especially ones that are overtly confessional. Elvis Costello refers to this music as “f— me, I’m sensitive.” (laughs) I’m a little tired of the “Hello, I’m having a feeling” situation, including when it’s me singing.

One of the most marked reinterpretations is “Two Hearts Beat as One,” which you turned into a kind of pared-down Philly soul/disco track. How did that evolve?

Edge: That’s me singing it. I did a demo vocal on pretty much everything, and on a couple of occasions Bono would go, “That sounds great. I’m happy for you to sing that one.” It happened with “Stories for Boys,” “Two Hearts,” “Desire” and “Peace on Earth.” We worked so fast. I recorded “Peace on Earth” in my bedroom with two microphones and a laptop. It took literally 10 minutes.

Some songs took longer. The first version of “Pride (in the Name of Love)” was too insipidly nice. We didn’t want this to be U2 Light.

Which versions of these songs will you be playing later this year at your Las Vegas residency?

Edge: Probably a combination. It’s going to be a rock ‘n’ roll show, for sure, and we’ll probably dip into these interpretations for part of it.

Bono: Some people say that the lifeblood of U2 is concerts, not our albums — which is very hurtful. (laughs)

Your Las Vegas residency, tentatively scheduled for the fall, will be your first live shows since December 2019. You’re initiating the MSG Sphere, which is being touted as a state-of-the-art concert hall. What’s different about it?

Bono: At the Sphere, the entire building is a speaker. We should be able to get to levels of intimacy that we’ve never had before in concert. That’s going to be interesting. Edge said to me, “You know, we rely on a certain degradation of signal.” I said, “I think I know what you mean, but go on.”

He said, “If we have full fidelity, we may not like what we sound like.” (laughs) We haven’t put tickets on sale because we don’t know yet that we can fulfill the potential of the place. Edge has gone in there with his hard hat — and his hard head — and so far, the results are good.

For the Vegas shows, you have Bram van den Berg on drums instead of Larry, who can’t play, reportedly due to neck and elbow injuries. In November, he gave a prickly interview in which he described the band as a dictatorship rather than a democracy and seemed very unhappy. Is Larry quiet quitting U2?

Bono: We have all quiet quit U2 over the years. After the article appeared, Larry texted me and said, “You probably won’t be asking me to do many interviews after this.” (laughs) He has a funny side, despite being caricatured as a surly fella. When I’m mouthing off about some disaster in the world and how we might be able to help, he’s looking at his watch and saying, “Hurry up. I want to see my kids, Bono.” That’s partly humor.

In the interview, he said the band had turned into a dictatorship, to which Edge replied, “There are four dictators in U2.”

Larry also said “Everyone has their limits. And you only do this if it’s a great time you’re having,” which sounds like a threat, doesn’t it?

Edge: Anyone can have a bad day, and I’m sure Larry was frustrated by not being able to perform with us in Vegas.

Is there a chance that I’ll wake up one morning and “Songs of Surrender” will have been automatically downloaded into my iTunes, as you did in 2014 with “Songs of Innocence”?

Bono: God bless Apple for allowing me to talk them into that, even if it went far past where it was meant to go. I hope we don’t stop looking for ways to get our music across. Slipping it under the pillows of our audience would be better for “Songs of Surrender” because they’re whispers, not screams, these songs.

It’s been 45 years since U2 first played in public. What does it take to keep the same four people together for so long?

Edge: It takes a lot of good luck. In our case, the origins of the band were based on friendship. As we got older, there was a sense of group purpose. We took on a band ego and left our own egos checked at the door because if the collective wins, we all win. That makes it so much easier to deal with each other’s idiosyncrasies. Most bands break up because one or more members decides they’d be better off being solo. It’s more every man for himself.

There’s a Gore Vidal quote: “It’s not enough to succeed, what you really want is for your friends to fail.” That’s not the case for us.

Gore Vidal also said, “Never miss a chance to have sex or appear on television.”

Edge: I fundamentally disagree. I think you have to be super-selective in both cases. (laughs)

The band has mentioned two new albums in progress: “Songs of Ascent” and something Bono calls a “noisy, uncompromising, unreasonable guitar album.” What’s the difference between the two?

Bono: “Songs of Ascent” is a reflective, lyrical album, very different from the unreasonable guitar record, which is not to say they might not end up mating. We didn’t want to put either album out before we could play live, so we were waiting for our drummer to heal.

After years of legal entanglements, and the recent death of one of its members, De La Soul’s first six LPs will soon be on streaming platforms.

Edge, here are three things Bono writes about you in his memoir: “Edge is the silence inside every noise,” “Edge is not a complainer and doesn’t do melodrama” and “Edge is from the future.” Are all of them true?

Edge: (laughs) The first two I’ll own up to. And “from the future” is a joke we’ve used a few times. Bono means I live in the future. I’ve come back here to reassure people that the future is, in fact, going to be OK.

He also says that when you were 15, your favorite album was “Close to the Edge” by Yes. Is that true?

Edge: It was one of my favorites. I probably learned how to play harmonics because of Steve Howe. Weirdly, my nickname was given to me a bit later, and I don’t think it was in reference to that album.

The biggest change on “Songs of Surrender” is in “Walk On,” which you released in 2000 and wrote for Aung San Suu Kyi, the Burmese political prisoner who won a Nobel Peace Prize and was later criticized, after she gained high office in Myanmar, for not objecting to the country’s persecution of Muslims. You rewrote it and now it’s about Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky. Why did you make that change?

Bono: Once I got the line, “If the comic takes the stage and no one laughs,” I had to finish it. President Zelensky, the most important person standing up for freedom, was a stand-up comic. I’m not surprised, because comedians are the truth-tellers of our time, more than rock stars are.

I felt so let down by Aung San Suu Kyi, like many people did. So I gave the song to another figure. Then President Zelensky invited us to Kyiv, and we went off to Ukraine [in May 2022] to sing it for him. You can’t do much as artists, but you can show solidarity.

The funniest thing was, we were busking on a train station platform and it was perfectly lit. We’re in the middle of a war! Who’s lighting the buskers like this? But, of course, Zelensky is an actor and comedian. His No. 2 is a film producer. Storytelling is essential for their survival, and he wanted it to look right.

Even before U2 had a record deal, we played an anti-apartheid show. We were insufferable from a very early age. (laughs) This is the arrogance of great songwriting. John Fogerty had it. Bob Dylan, Kendrick Lamar, John Lennon, Bob Marley … If U2 communicated anything, outside of the personal conversations of our songs, I hope it was: The world is more malleable than you think. These immovable objects are not immovable.

So it’s always been important for you that the music is of some use?

Bono: We try to, but if it’s a s– song, it’s like, “No! Don’t make things worse! No more U2 songs!”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.