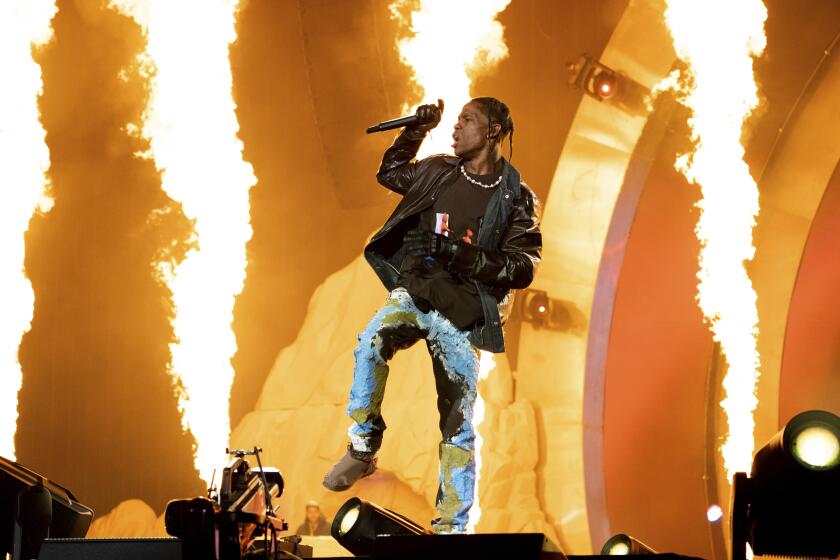

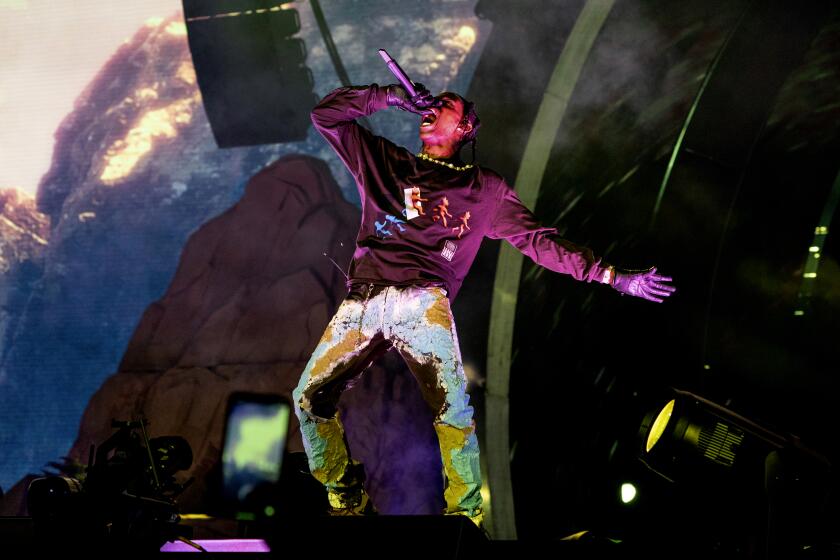

For Travis Scott, a history of chaos at concerts, followed by a night of unspeakable tragedy

In Travis Scott’s 2019 Netflix documentary “Look Mom I Can Fly,” in the aftermath of a particularly volatile May 2017 show at the Walmart Arkansas Music Pavilion in Rogers, Ark., one fan beamed at a camera crew while leaning on crutches. “I survived, I survived! It’s all good!” they said.

Following the show, Scott faced three misdemeanor charges of inciting a riot, disorderly conduct and endangering the welfare of a minor after he invited fans to overpower security and rush the stage. Scott pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct and had to pay more than $6,000 to two people injured at the show.

“I just hate getting arrested, man. That s— is whack,” Scott said in the documentary, upon his release from jail.

Eight people died and 25 were hospitalized after crowds surged at the Travis Scott’s Astroworld Festival in Houston on Friday.

Scott’s talent for stirring up a young fanbase with the fury of an underground punk act has long been a part of his appeal. On his 2018 song “Stargazing,” the rapper reveled in his crowds’ heaving energy: ”it ain’t a mosh pit if ain’t no injuries.” Yet the 30-year-old rapper is also one of the most successful figures in contemporary hip-hop, an endorsement-friendly business mogul in the vein of Jay-Z and Puff Daddy, and one of a handful of rap artists who can headline major festivals. His reputation as an incendiary live performer arguably exceeds his recorded music as the main driver of his current popularity.

But that penchant for inspiring chaos onstage has led to troubling situations, long before Friday’s Astroworld crowd-stampede disaster that killed eight people and left numerous concert-goers injured in Houston.

Scott has twice faced criminal charges related to inciting crowds into over-heated fervors. Before the incident in Arkansas, the rapper pleaded guilty in 2015 to charges of reckless conduct, after cajoling fans at Lollapalooza to climb over barricades and onto the stage with him during his show at the Chicago festival.

“Everyone in a green shirt get the f— back,” Scott said, referencing the festival’s security staff. “Middle finger up to security right now.” He then led the crowd in a chant of “We want rage.” (Scott often refers to his fans as “ragers.”)

Scott’s set lasted barely five minutes, whereupon he fled the scene and was soon apprehended by local police. A judge ordered him under court supervision for a year following his guilty plea.

In April 2017, a man named Kyle Green sued Scott after he attended a show at Terminal 5 in New York City, where Green claims fans pushed him off an upper-deck balcony. A different fan jumped from the same balcony in a widely seen video, after Scott pointed him out and encouraged him to leap off. “I see you, but are you gonna do it?” Scott said from the stage. “They gonna catch you. Don’t be scared. Don’t be scared!”

Green was left partially paralyzed by the incident. Reached by Rolling Stone after the Astroworld incident, an attorney for Green said that he’s ”devastated and heartbroken for the families of those who were killed and for those individuals who were severely injured. He’s even more incensed by the fact that it could have been avoided had Travis learned his lesson in the past and changed his attitude about inciting people to behave in such a reckless manner.”

In 2019, Scott wrote “DA YOUTH DEM CONTROL THE FREQUENCY,” on an Instagram video of fans storming barricades at one of his shows. “EVERYONE HAVE FUN. RAGERS SET TONE WHEN I COME OUT TONIGHT. BE SAFE RAGE HARD. AHHHHHHHHHHH.” Three people were hospitalized following a crowd stampede over security barriers at the 2019 edition of the Astroworld Festival.

“I could never imagine the severity of the situation,” Travis Scott said in his latest statement on the Astroworld Festival, where eight people died.

The 30-year-old Scott, whose real name is Jaques Webster, was born in Houston, a famed city for outlaw hip-hop that figures prominently in his work (His chart-topping 2018 album “Astroworld” was named after a now-closed local theme park). His father and grandfather were jazz and soul musicians, and he studied musical theater while growing up in the middle-class Houston suburb of Missouri City. In 2012, he signed deals as an artist (with T.I.’s Grand Hustle imprint for Epic) and as a writer/producer (with Kanye West’s G.O.O.D. Music). His music was both visceral and melancholy, produced with the weight and ferocity of trap but glazed over with vocal processing and distended samples.

On two early mixtapes and his 2015 major-label debut “Rodeo,” singles like “Antidote” set a template for how rap would sound in the coming decade — bruising, miserable, sleekly nihilist. The LP’s swarm of guest appearances — Justin Bieber, the Weeknd and Kanye West among them — announced that a new star had arrived.

His 2016 follow-up, “Birds in the Trap Sing McKnight,” had similar firepower, with Andre 3000, Kendrick Lamar and Kid Cudi as guests. That record yielded two of his signature singles — “Goosebumps” and “Pick up the Phone” — and topped the Billboard 200 album charts.

But it was 2018’s “Astroworld” that turned him into a pop force. It not only again topped the album charts, but placed all 17 tracks into the Hot 100 singles chart. “Sicko Mode,” with Drake, topped the Hot 100 and set a template for TikTok-ready rap with its hard edits between beats and tempos.

His arena tour for that album grossed $32 million in three months in 2019, according to Pollstar. That launched Scott into the caliber of acts that could headline the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, for which he was booked in 2020 and, as of now, is still scheduled to headline in 2022. (He is also currently scheduled to headline next weekend’s Day N Vegas festival, alongside Kendrick Lamar and Tyler, the Creator.)

Last year, more than 27 million fans logged in to see him perform a concert in the video game “Fortnite,” where fans bought reams of real and virtual merchandise for characters in the game.

Beyond music, his endorsement deals with Nike, at a reported $10 million per year, and McDonald’s, where fans could order a Scott-themed novelty meal, have made him one of the richest acts in contemporary hip-hop. This year, he launched a hard seltzer brand, Cacti, with Anheuser-Busch. Scott has a daughter, Stormi, with the reality TV and cosmetics mogul Kylie Jenner.

Scott founded the Astroworld Festival in 2018 in partnership with Austin-based ScoreMore Shows and Live Nation, the world’s largest event-promotion company (ScoreMore sold a controlling interest to Live Nation in 2018). This year’s lineup, at NRG Park in Houston, was to feature Tame Impala and Bad Bunny on Saturday, which was canceled following the events of Friday night. SZA, Lil Baby and Roddy Ricch performed before Scott on Friday.

In the run-up to the festival, Scott opened a community school garden initiative in Houston, Cactus Jack Gardens; a new basketball court at the city’s Sunnyside Park; and a design-centric academy partnered with Parsons School of Design. Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner told the New York Times that “I’ve worked with the family, I’ve worked with Travis, I’ve worked with his mom...This is the last thing any of them wanted to see happen.”

But on Friday, the festival experienced problems from the outset, as crowds overwhelmed security and broke through the entrance gates in the afternoon. At the outset of Scott’s 25-song set, fans were crushed, some fatally, as the crowd of 50,000 surged forward. Social media filled with clips of fans desperately pleading with Scott to stop the show, including some who climbed onstage to tell crew that audience members were hurt. Eight people, one as young as 14, died during the stampede.

The tragedy has left the rap world reeling. Ricch promised to donate his entire performance fee from the festival to the affected families. Scott’s team spent some of Saturday’s post-concert aftermath deleting social media posts that seem to encourage gate-crashing or other illicit behavior, including one May 2021 Twitter post in which he said: “We still sneaking the wild ones in. !!!!”

Judge Lina Hidalgo, the senior elected official in Harris County, where Houston is located, said at a news conference following the festival that “It may well be that this tragedy is the result of unpredictable events, of circumstances coming together that couldn’t possibly have been avoided. But until we determine that, I will ask the tough questions.”

One Astroworld attendee has already sued Scott, his guest performer Drake, Live Nation and the Harris County Sports & Convention Corp., which owns NRG Stadium. Texas attorney Thomas J. Henry filed the lawsuit Sunday on behalf of Kristian Paredes, according to the Daily Mail, accusing the defendants of prioritizing “profits over their attendees.”

“Live musical performances are meant to inspire catharsis, not tragedy,” Henry said in a statement. “Many of these concert-goers were looking forward to this event for months, and they deserved a safe environment in which to have fun and enjoy the evening. Instead, their night was one of fear, injury, and death.”

In a video posted late Saturday, a weary-looking Scott said that while he was onstage, “anytime I could make out anything that’s going on, I stopped the show and helped them get the help they need,” he said, “We’ve been working closely with everyone trying to get to the bottom of this.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.