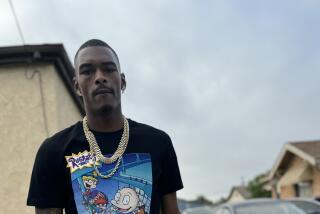

Compton Cowboy Randy Savvy has lost friends to violence. This time, he put his grief to song

It was a story Randy Savvy had heard countless times before: Another Black man had been killed in Compton. Hearts and lives were shattered. A community grieved.

In early 2020, Savvy, born Randall Hook, learned that a friend’s boyfriend was fatally wounded by gunfire on his way to a store.

Savvy, 31, understood her grief. He’s lost loved ones to gang violence too.

He wrote “Colorblind,” his first single, in response.

“That song came from a really inspired place of thinking about the life that we live in inner cities, how we lose lives and how it just seems to be a normal way of life in our culture,” said Savvy in a phone interview. “It’s a toxic, tragic cycle: People die. There’s a little celebration to honor their life. Then the next person dies and the same thing happens. The next person dies and the same thing...

“It’s really saddening to me.”

In 2020, homicides in Los Angeles County rose by 20%, to the highest level in a decade. Much of the violence occurred in South L.A. In November, Los Angeles reached a bloody benchmark not seen in a decade with 300 homicides in a single year, the first time since 2009. Shootings increased more than 32%. Much of the surge has been fueled by gang violence.

As the leader and cofounder of the Compton Cowboys, Savvy has dedicated his life to curbing cycles of gang violence. He learned to ride horses as a kid in what was then called the Compton Junior Posse, a riding and gang-prevention program founded in 1988 by his aunt, Mayisha Akbar, in Richland Farms.

Walter Thompson-Hernández, author of “The Compton Cowboys,” joined Metro reporter Angel Jennings for a virtual chat about his new book.

Several years ago, after his aunt retired, Savvy took over the nonprofit and rebranded it the Compton Junior Equestrians, entrusted with the huge responsibility of reshaping the organization for a new generation. In 2017 he founded the Compton Cowboys, a group of childhood friends working to fight harmful stereotypes about Black people and Compton with horseback riding.

Its members adopted the doctrine: “Streets raised us. Horses saved us.” Walter Thompson-Hernández, who grew up seeing the Black men and women riding horses in the streets of South L.A., wrote about them in his debut book, “The Compton Cowboys: The New Generation of Cowboys in America’s Urban Heartland,” published last year.

Savvy grew up listening to West Coast rap icons like N.W.A, Snoop Dogg and DJ Quik. At rodeo shows, he’d often blast country stars such as Alan Jackson, Toby Keith and Reba McEntire. When he started writing music with friends as a teenager, those two musical worlds sometimes collided. Their first song, “My Wood,” about being “cool” and “flier than everybody else,” was a remix of and a play on Young Jeezy’s “My Hood.”

“We were terrible but we had so much fun doing it ... it never occurred to me that I would end up wanting to take music seriously as a career,” said Savvy.

That drive established itself while Savvy was studying for his bachelor’s in sociology at Occidental College years later. By the time he founded Compton Cowboys, Savvy “had found himself and what I wanted to do in the world.” Music was at the fore.

“When someone says something is colorful, that’s usually a good thing,” said Savvy of “Colorblind.” “Colors are normally inspiring and can make you feel good, like the rainbow, art, paint, stuff like that. But colors in the context of the ’hood are really traumatizing.”

Walter Thompson-Hernández’s “The Compton Cowboys: The New Generation of Cowboys in America’s Urban Heartland” tells a grand story in granular detail.

Savvy associates red and blue with the lights of police cars and the rival Crips and Bloods gangs. The color green makes him think about “the things people do for money in the ’hood.” Yellow elicits thoughts of yellow barricade tape found at crime scenes. White conjures chalk on the ground.

As for the color black, he imagines Black faces, lifeless, lying on cold concrete.

“Sometimes I wish I was colorblind because then I wouldn’t see these traumatizing colors all the time … maybe my life wouldn’t be so emotionally unstable seeing all this,” he said.

In the spring, as the deadly coronavirus swept through the United States and disproportionately affected communities of color, Savvy found himself struggling to maintain the ranch and its horses. Film and TV production came to a grinding halt, extinguishing a big financial source for the ranch.

Savvy turned his panic into hustle: He called and emailed “the big playmakers” from Compton he thought could lend a hand. Dr. Dre, a fellow Compton native and among his musical idols, was top of mind.

Through a series of networking connections, the two men got in touch. Dre offered a year’s worth of funding for horse feed. He asked what else was going on.

Savvy was reluctant to mention his musical inclinations because “in my head I’m like, ‘I’m sure everybody that talks to Dre tells him that they have music,’” he recalled. But he went for it. Among the songs he sent him, “Colorblind” stood out to Dre. They left it at that.

Fast-forward months later when George Floyd, a Black man in Minneapolis, was killed at the hands of a white police officer. Black Lives Matter protests erupted, and “Colorblind” suddenly took on a new meaning.

“The chorus, the lyrics, go: ‘Red light blue light yellow tape black face white chalk on the ground.’ Originally, that addressed a murder scene. The police are there investigating and handling the murder scene of somebody who got killed in the streets as a result of gang violence,” said Savvy.

But in the context of Floyd and the BLM movement, he thought: “This murder scene, maybe the police killed this man that’s on the ground. So these red and blue lights, these cop lights that are there, are not there as a reaction, they’re the potential suspects to this murder.”

He called up Dre, who excitedly agreed to mix the track. Savvy officially released the song and music video in late November. The music video features some of Savvy’s beloved horses, footage from BLM protests and scenes of Dre and the Compton Cowboy recording in the studio.

Last month, Savvy dropped a live acoustic performance of “Colorblind” on his Instagram page. Shot in Richland Farms — his Tennessee Walking Horse Goldie Loc in the background and friend George Magallanes Jr. on a nylon-stringed guitar — Savvy raps:

I wonder will it ever change

Been praying all my life for better days

Too many vacations

Mamas pillows looking like they been out in the rain and n— still gang banging

Nah I can’t blame them

Tell me what you would do if that was the only family you ever knew

Red or blue you gone die for them because they done died for you that’s the truth

Eulogies to prove it

The song, said Savvy, is about love and valuing life. But more specifically, it’s a call to action to end the gang violence that has afflicted neighborhoods like his for generations.

“I’m hoping that young cats on the streets can hear it and it’ll awaken a message for them of like, ‘Maybe I should put the gun down’ or ‘Maybe I should try to go legit with what I’m doing for money.’ We have to stop hurting our community and killing each other before we even get a chance to maximize our potential.

“I’m tired of seeing Black and brown bodies on the streets and hurting our families, our mothers, everybody,” he added. “There’s just too much hurt in the ’hood, and we’re self-inflicting a lot of that hurt. We have to address that from inside.”

Savvy will release his six-track EP, “Late Night Ride,” later this year.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.