Column: Just when they need it most, 800 Compton residents are about to get free money

For five years, Georgia Horton had worked to rebuild her life, no easy task for a Black woman who spent years in prison.

She found an apartment in Compton. She started working as a motivational speaker and evangelist. She wrote a book. She found her home church. But, in just one day, it almost all fell apart again.

In December, Horton found herself on the verge of eviction. She was hopelessly behind on her rent, her income gutted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The odd jobs she was doing to make up for lost speaking gigs, particularly at shuttered prisons, detention facilities and community centers, were no longer cutting it.

If not for an out-of-the-blue invitation to join the “Compton Pledge” — among the largest and most ambitious guaranteed income experiments in the U.S. to date — Horton probably would’ve ended up on the streets.

“It really made me able to breathe again,” she said. “To reset and say, ‘OK, now we can, you know, get back on track.’ And try to think not just what to do during the pandemic, but beyond the pandemic.”

Horton is one of some 800 Compton residents who, by the end of February, will be receiving between $300 and $600 every month, no strings attached. They will get the deposits on prepaid debit cards or through Venmo for the next two years.

The hope is that, by giving struggling people a bit more financial stability, they will be able to move from merely surviving to thriving. And with COVID-19 continuing to wreck lives and the economy in Southern California, there’s perhaps no better time and no better place to study how cash infusions can help people escape poverty. Ultimately, though, the effectiveness will be judged by data.

No public money is being used to provide guaranteed income. Rather, an unknown number of anonymous private donors are bankrolling the Compton Pledge, which is being managed by the Fund for Guaranteed Income, a charity led by Nika Soon-Shiong, the daughter of Los Angeles Times owner Patrick Soon-Shiong.

She also is a co-director of the Compton Pledge. But it is Mayor Aja Brown who has become the face and biggest proponent of it.

The way the mayor sees it, entrenched economic inequality leaves people trapped. And, in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, severely sick and dead.

Latino and Black communities have been disproportionately hard hit since the beginning of the pandemic. Members of those communities are now dying at rates far worse than at any previous point in the COVID-19 crisis.

Consider that Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital, a few blocks from Compton in the unincorporated Willowbrook neighborhood, has been one of the busiest hospitals in Los Angeles County in recent weeks. And that’s saying something, given that 1 in 3 Los Angeles County residents have been infected with the coronavirus.

Brown has watched the ambulances come and go. What bothers her most is that so many of the patients inside are Black and Latino essential workers. When we spoke last week, the mayor lamented how, almost a year into the pandemic, we see it as normal that millions of poor people risk their lives for a paycheck every day, stocking grocery store shelves and delivering packages to support millions of affluent people who get to work from home.

“That disparity of choice is something that really is a public health concern,” she said. “There are just certain segments of people who are disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, and amplified by the systemic disparities and injustices.”

How many workplace super-spreader events would Los Angeles County have avoided if essential workers had enough money to pay rent and, therefore, felt free to take two weeks off at the first sign of a cough or fever? How much safer would we all be if the least among us had options?

Horton is living the answer as a participant in the Compton Pledge.

Once the Bakersfield native realized that she was starting to run out of money, she started cooking meals and selling them on street corners to make ends meet. She also started going to farmer’s markets to sell copies of her book, “Elegant Sister, What Happened?”

Horton knew that by being around so many strangers, she was putting herself at risk for COVID-19. But she felt she had no choice.

“I had to do what I had to do to eat. I had to survive,” she said. “I need that money in my hand.”

::

It wasn’t that long ago that almost no one supported the distribution of free money for people to spend however they wanted. Pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps Republicans despised the idea as a handout and moderate Democrats dismissed it as un-American.

But a double-digit rate of unemployment has a way of changing things. Two rounds of stimulus checks later, and the narrative has forever been altered. If not for those checks from the congressional coronavirus relief packages, the U.S. economy would have cratered and millions more would have suffered as states order businesses to close to slow the spread of COVID-19.

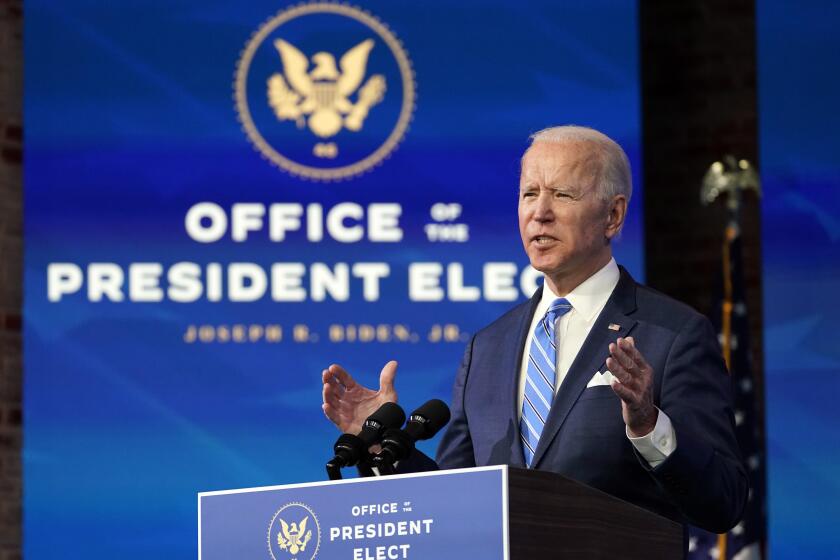

Now, Gov. Gavin Newsom has said that he wants to send “Golden State Stimulus” checks worth $600 to the neediest Californians. And on Thursday, President-elect Joe Biden announced a plan to send another round of checks to Americans, this time for $1,400.

This is a much different political landscape than what then-Mayor Michael Tubbs faced in early 2019, when he launched the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration to give 125 residents $500 a month for 18 months.

President-elect Joe Biden’s pandemic response plan centers on a mass vaccination campaign and closer coordination among all levels of government.

Back then, much of the push for guaranteed income was coming from Silicon Valley types, who were eager to convince lawmakers to help soften the blow as their technology disrupted industries. What better way to take care of truck drivers and cabbies sidelined by autonomous vehicles?

The organizers of the Compton Pledge, in contrast, are overt about their goals of addressing systemic racism and inequities. In fact, that’s why Brown’s city was chosen.

Nearly 70% of residents are Latino and 30% are Black. About 20% of households are below the poverty line. Many residents are undocumented immigrants or, like Horton, were incarcerated, making them ineligible for many government benefits.

Unlike in Stockton, the organizers of the Compton Pledge worked to specifically include those immigrants and ex-offenders among the pool of participants. To do so, they provided the city and several community groups with parameters for the experiment, including an ideal age range and income level, and got back a list of thousands of potential candidates. From there, the list was anonymized and selected for invitations largely at random.

Once the experiment is fully underway with all 800 participants, the nonprofit Jain Family Institute, which designs guaranteed income programs, will conduct several studies, including on spending habits. More rigorous, academic research will come later with the goal of influencing state and federal policy.

There is a lot riding on the findings, given the yawning economic need made worse by the pandemic. But Brown isn’t worried.

“I believe that the body of data that will be formulated through this pilot will help really lay the groundwork and make the case with empirical data that this is a necessary vehicle to begin to undo systemic racism in a tangible way,” she said. “And in a way that actually can be measured.”

In other words, money can’t buy everything, but it can buy options.

For Horton, it bought hope.

“I was ecstatic,” she said, explaining that it took a flurry of emails and a couple of phone calls to believe that the offer to join the Compton Pledge was really real. “It was dark not knowing how things were going to work [out], and when that came, it brought hope. It was a light.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.