Deaths among Latinos in L.A. County from COVID-19 rising at astonishing levels

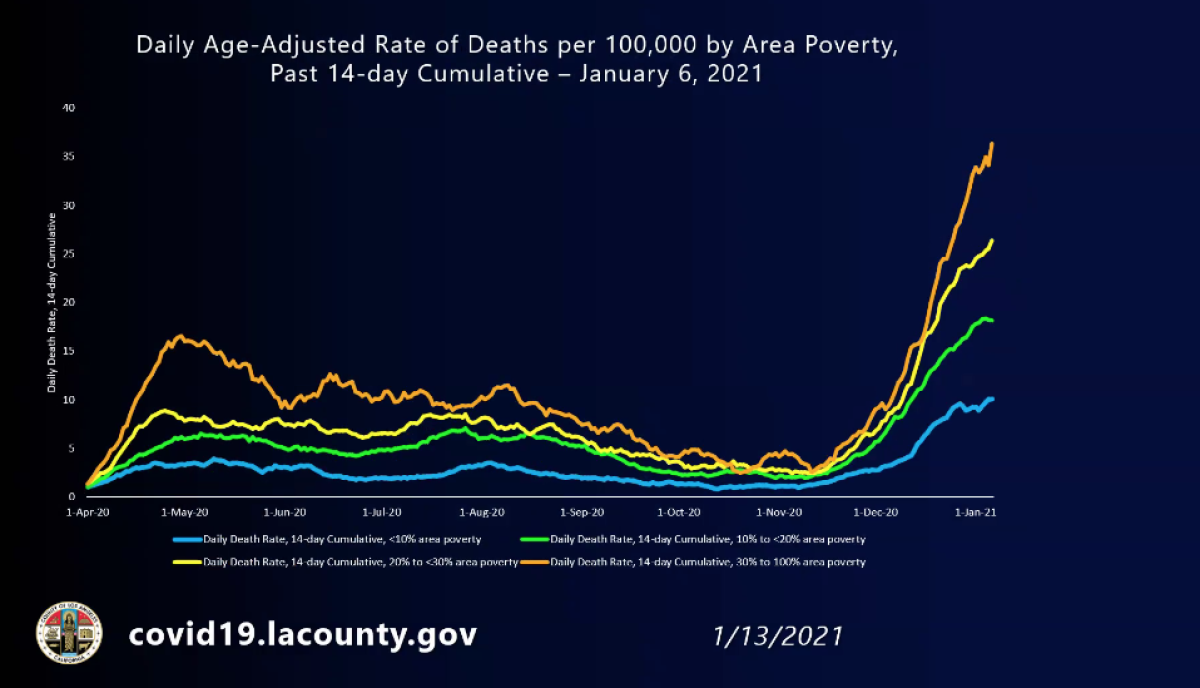

As the coronavirus spreads relentlessly through Los Angeles County, poor neighborhoods and the region’s Latino and Black communities continue to bear the brunt of illness and death, according to data released Wednesday.

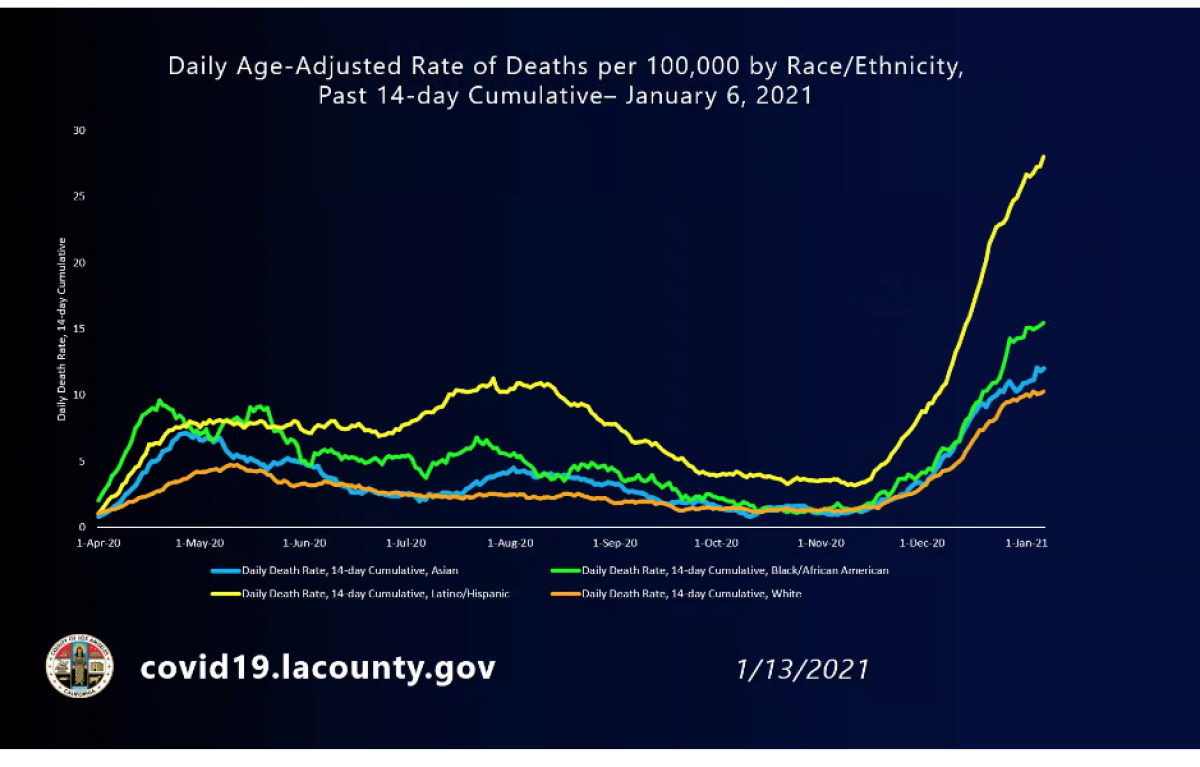

These groups have been disproportionately hard hit since the beginning of the pandemic, but the gap had eased during the summer. That progress has disappeared and members of those communities are now dying at rates far worse than at any previous point in the COVID-19 crisis.

Latino residents were nearly three times as likely, and Black residents nearly twice as likely, to be hospitalized with COVID-19 as white residents.

People living in the most impoverished neighborhoods of the county are now averaging about 36 deaths a day per 100,000 residents. By contrast, those living in the wealthiest areas are experiencing about 10 deaths a day per 100,000 residents.

Latino residents in L.A. County are dying at an astonishing eight times the rate they once did — from 3½ daily deaths per 100,000 in early November to 28 deaths a day now for every 100,000.

“This is a staggering increase of over 800% in a very short amount of time,” said L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer.

Poor Latino neighborhoods are highly susceptible to COVID-19 spread because of dense housing, crowded living conditions and the fact that many who live there are essential workers unable to work from home. Officials believe people get sick on the job and then spread the virus among family members at home.

The COVID-19 mortality rate among Black residents soared from 1 death a day per 100,000 to more than 15 deaths a day per 100,000.

“Deaths have also increased dramatically among our Asian residents,” Ferrer said. The death rate among Asian American residents has grown from 1 to 12 daily deaths per 100,000 residents.

White residents now have the lowest rate of death among the other racial and ethnic groups — 10 deaths per 100,000 residents. That’s an increase from 1 death per day per 100,000 in early November.

The data were released as the death toll continued to climb. L.A. County reported 266 COVID-19 deaths Wednesday, the fourth highest single-day total of the pandemic, pushing up the daily average of deaths over a weekly period to 232, a record. In the last week alone, 1,623 COVID-19 deaths have been reported.

On Wednesday, 12,121 new coronavirus cases were reported. The average number of new cases reported daily is now more than 15,100 — a level Ferrer has warned is a danger sign for even more COVID-19 patients entering L.A. County’s already overwhelmed hospitals.

Local health jurisdictions in California reported 520 COVID-19 deaths on Wednesday, the fifth-highest single-day tally. An average of 514 COVID-19 deaths are now being reported every day in California on a weekly basis, close to the all-time high.

Nearly every street corner holds some sign of the virus that has upturned lives, changing how the community mourns, learns, works and worships.

More than 40,000 coronavirus cases were reported in California on Wednesday; the state is now averaging about 43,000 new cases a day over the past week, just shy of the all-time high of about 45,000 cases a day.

L.A. County has cumulatively reported more than 959,000 coronavirus cases and 12,972 COVID-19 deaths. California has reported 2.8 million cases and 31,676 deaths.

California’s Latino and Black residents and people with no more than a high school degree suffered among the highest increase in deaths during the pandemic, according to an analysis by researchers at UC San Francisco published in December.

“A shutdown is beneficial only to a certain segment of the population,” said UC San Francisco epidemiologist Yea-Hung Chen, the lead author of the study, which is published in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine. “It’s saying that we want to protect those who can work from home, but we’re not applying the same sorts of protections to other people.”

By contrast, among people who had graduate and professional degrees, there were hardly any excess deaths during California’s springtime stay-at-home orders. Certainly, there were people with such degrees who did die of COVID-19, but the overall deaths among that group were not significantly higher than would be expected in a pre-pandemic year.

The study also showed that California’s springtime stay-at-home orders did result in declines in deaths among other racial groups.

“The lockdown that we had early does seem to be to coincide with declines in mortality,” said coauthor Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, chair of the UC San Francisco department of epidemiology and biostatistics. “What it means is that even our most effective strategies need to be coupled with a focus on the communities that are most vulnerable and ensuring that they have the resources in order to be able to to protect themselves, even in the midst of effective strategies like the lockdown.”

California counties with a greater share of low-wage and crowded households have been more likely to be hit hard by the pandemic, according to a study by the UC Merced Community and Labor Center last year.

Latino workers have the highest rate of employment in essential front-line jobs where there’s a higher risk of exposure to the coronavirus, according to the UC Berkeley Labor Center. For instance, 55% of Latinos work in such jobs and 48% of Black residents do as well, compared with 35% for white residents.

Latinos make up 93% of farmworkers; 78% of construction workers; 69% of cooks; 60% of laborers and material movers; 57% of truck drivers; 55% of cashiers; and 52% of janitors and building cleaners. Latino residents make up 39% of California’s population.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.