In alarming shift, Latinos getting coronavirus at more than double rate of whites in L.A. County

Latino residents are bearing the brunt of an unprecedented surge in coronavirus infections, underscoring the racial and economic inequities the pandemic has had in California, and particularly in Los Angeles County.

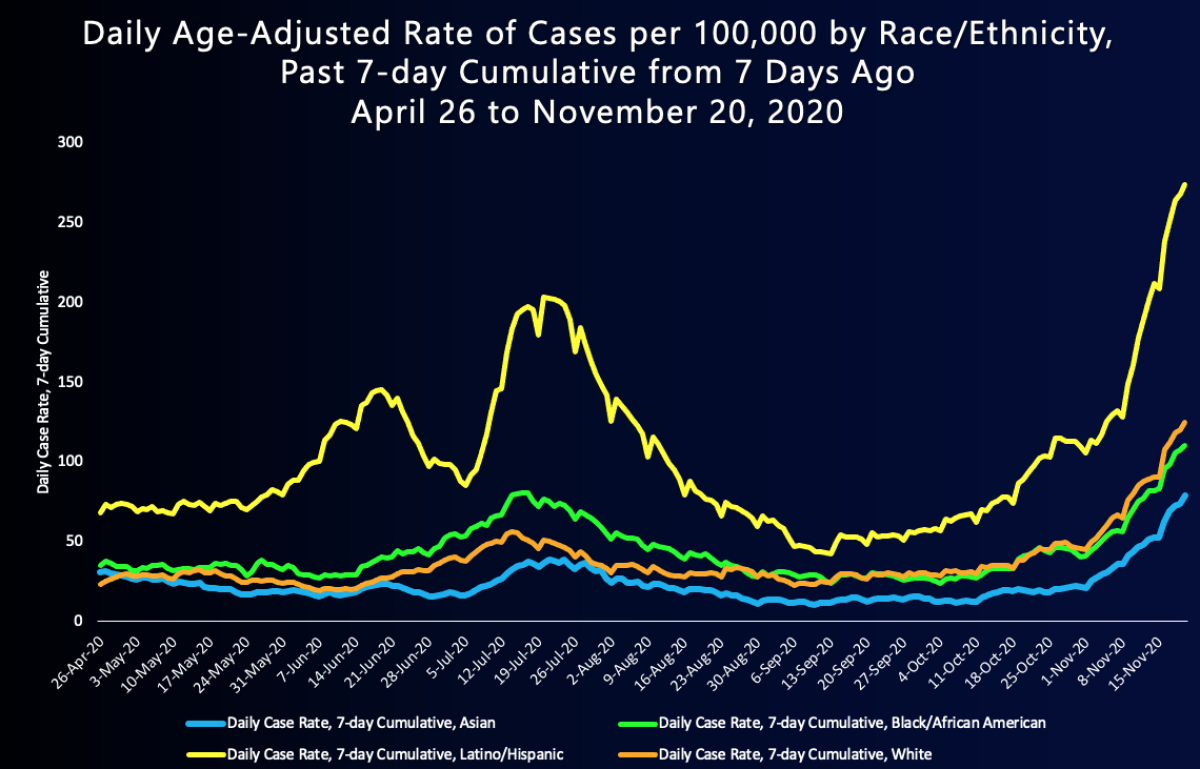

In L.A. County, Latino residents are now becoming infected with the virus at more than double the rate of white residents, according to data.

The increase is a reversal in progress the county saw in the late summer and early fall as the disparity among racial and ethnic groups lessened and the overall spread of the virus flattened. In August, county officials expressed optimism as COVID-19 infection rates and deaths in the Latino and Black communities tumbled. Now they are sounding new alarms.

“It is very clear and quite alarming that certain groups are once again bearing a greater burden than others,” Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said recently. “The gaps between race and ethnicity groups, where we made a lot of progress in closing in September, have now once again dramatically widened, particularly for our Latino residents. All groups, as you’ll see, are in fact experiencing increases.”

Latino communities are at higher risk for the illness for several reasons. They tend to be essential workers who must go to retail stores, manufacturing plants and other sites rather than working from home. That puts them at a great risk of contracting the virus. Some Latino neighborhoods are more densely populated, making the virus easier to spread.

In the coming weeks in L.A. County, hospitals will try to choreograph their staffing to best meet the needs of critically ill patients.

By mid-November, the age-adjusted daily case rate among Latino residents was about 274 cases per 100,000, more than double the case rate among white residents, which was 125 cases per 100,000. (Statistics that are adjusted to account for age differences among racial and ethnic groups provide more meaningful comparisons, according to epidemiologists.)

The gap had been less pronounced before the latest surge hit.

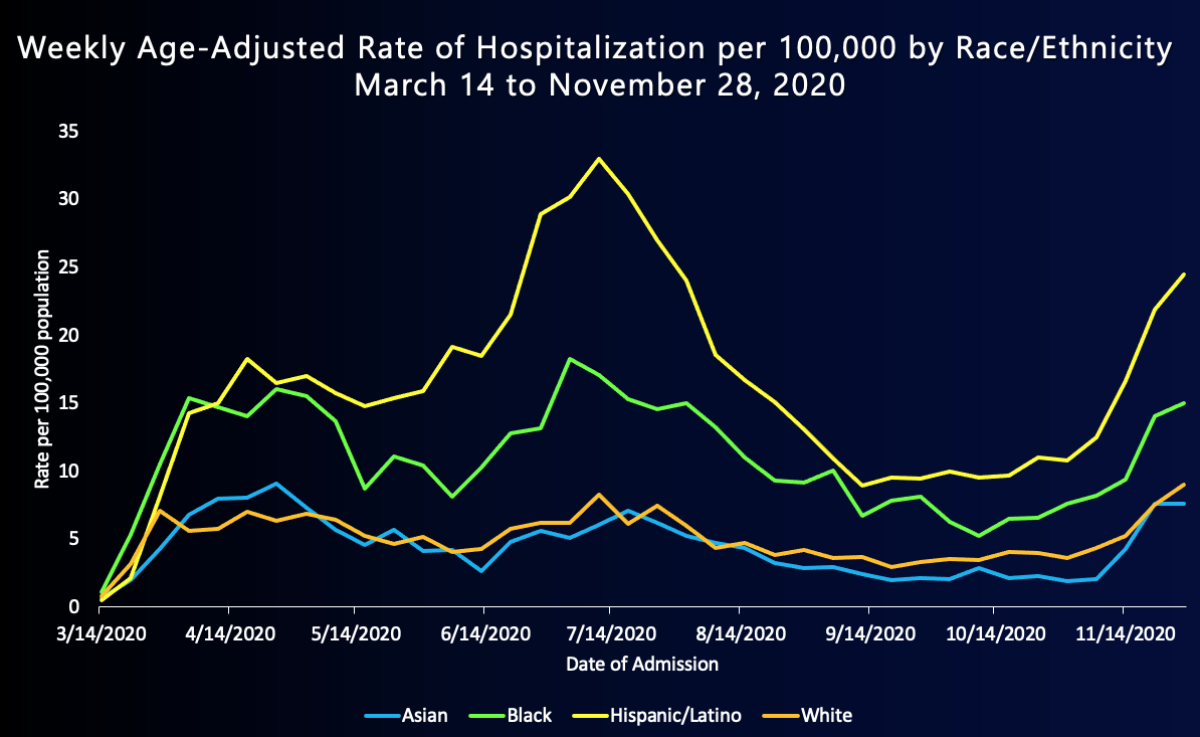

Latino and Black residents have disproportionately higher rates of hospitalization for COVID-19 than white residents.

Latino residents were nearly three times as likely, and Black residents nearly twice as likely, to be hospitalized after contracting the virus as white residents. While 9 of every 100,000 white residents were hospitalized for the most recent weeklong period available, in mid-November, the rate of weekly hospitalizations was 15 for every 100,000 Black residents and 24 for every 100,000 Latino residents.

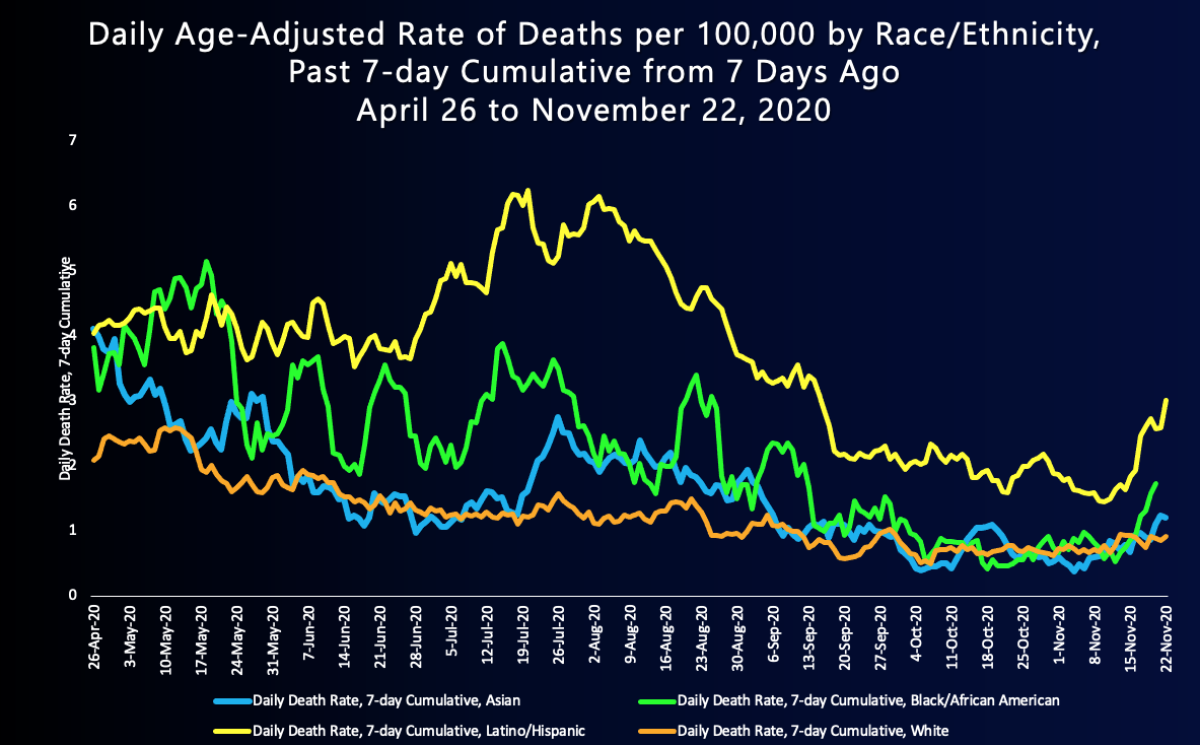

In recent weeks, the COVID-19 death rate has jumped among Latino and Black residents. Among white and Asian American residents, the death rate as of mid-November has been fairly stable.

Latino residents had a daily age-adjusted death rate of 3 deaths per 100,000; among Black residents, the rate was 1.7 deaths per 100,000; among Asian American residents, it was 1.2 deaths per 100,000; and among white residents, 0.91 death per 100,000.

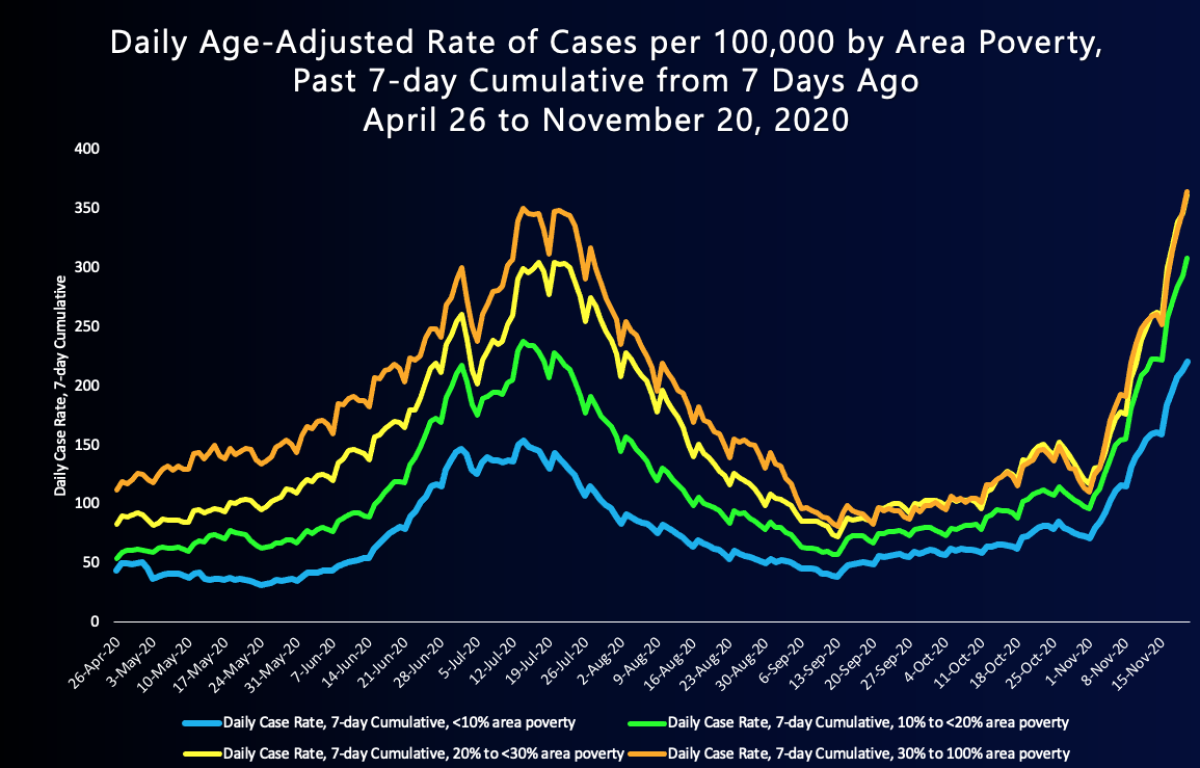

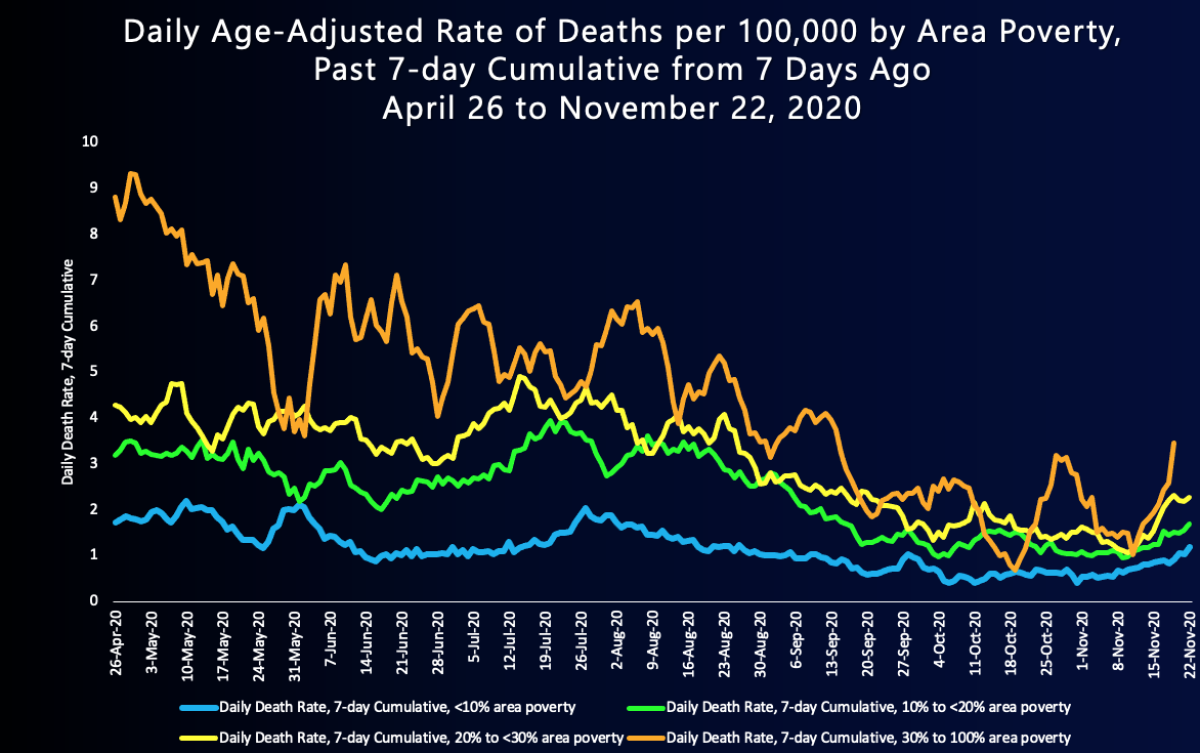

The chances of infection and death from COVID-19 also remain disproportionately higher among residents living in impoverished areas of Los Angeles County.

Those living in the poorest areas of L.A. County had a 65% higher rate of contracting the virus than those in wealthier areas. For a seven-day period in mid-November, people in areas with the highest poverty levels had an age-adjusted rate of 364 coronavirus cases per 100,000 residents, while those living in the wealthiest areas reported a rate of 221 coronavirus cases per 100,000 residents.

Death rates are also worsening among people in impoverished areas.

“As overall deaths have begun to increase, we see that people in the lowest-resource areas are bearing a great deal of this burden,” Ferrer said. “Death rates among people and communities with high rates of poverty is around three times that of people living in areas where there are more resources.”

Five of the 25 communities with the highest infection rates in L.A. County are in the northeast San Fernando Valley — in ZIP codes with high rates of crowded housing and areas that are home to large numbers of essential workers who are at prime risk of infection.

A statewide Times analysis showed that other heavily Latino areas are also among the hardest hit by the pandemic. Such communities along the 10 Freeway corridor in San Bernardino County have some of the state’s highest case rates, including in Bloomington, Colton, Fontana, Montclair, Rialto and San Bernardino, as well as those in the high desert, such as Adelanto, Hesperia and Victorville.

The same demographics are playing out across the state: In border communities in San Diego and Imperial counties, such as Calexico and San Ysidro; in agricultural communities in the Central Valley and Coachella Valley; and in a community in Berkeley, where an outbreak has spread among hundreds of workers at the Golden Gate Fields racetrack.

California has recorded more than 20,000 COVID-19 deaths. Latino residents account for nearly half of those, even though they represent only 38% of the state’s population, according to state data. They also represent 58% of total coronavirus cases.

Ferrer said it’s imperative that workplaces properly enact COVID-19 safety protocols, such as at manufacturing and food processing plants and grocery and retail stores.

“Those on the frontlines keeping healthcare facilities open, transportation and energy systems working and making sure that we are safe ought not to be asked, once again, to bear the brunt of rampant community transmission,” Ferrer said.

On Monday, she released data showing that less than 60% of workplaces visited by inspectors during a recent week were fully compliant with COVID-19 safety rules.

In L.A. County, only 61% of restaurants and bars visited between Nov. 25 and Thursday complied with coronavirus rules: 71% of gyms were in compliance, as were 69% of retail stores and indoor malls, 48% of food markets and 46% of hotels. None of the 14 garment manufacturers visited by the county was in full compliance.

Violations included workers and customers not wearing masks, and a failure to follow physical distancing and cleaning requirements, Ferrer said.

Nearly everything about Sunday’s 89th annual Virgen de Guadalupe procession and Mass was different from the year before: a new location, at the San Gabriel Mission, a scant crowd and social distancing.

The reality of COVID-19 in the Latino community was on display Sunday at the 89th annual Virgen de Guadalupe procession and Mass. There were still floats and celebrations, but the format was changed to avoid crowds and encourage social distancing.

This year’s procession — in San Gabriel — was the first held outside Los Angeles and the first in years to be relocated from Cesar E. Chavez Avenue in East L.A., in part to discourage large crowds.

Mass was limited to 120 in-person, physically distanced participants, but it was also livestreamed to 5,800 viewers, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles said.

Margarita Hernandez said it was more important to be involved in the event, even if changes had to be made to keep people safe.

“This has been a crazy year, and we needed this,” said Hernandez, 19, whose parish is St. Dominic Savio in Bellflower. “We have a chance to escape our house for a little while, but also to be safe and honor Our Lady of Guadalupe.”

Added Los Angeles Archbishop José H. Gomez: “This year, it was particularly important to continue this beautiful tradition celebrating the Virgen de Guadalupe because she is the mother of healing and hope.”

Times staff writer Ruben Vives contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.