Chick Corea, pioneering jazz pianist who helped define ‘fusion,’ dies at 79

Chick Corea, the Grammy-winning pianist and keyboardist whose work at the intersections of jazz, experimental music, funk, progressive rock and classical music with his band Return to Forever helped define the sound of jazz fusion in the 1970s, has died.

Corea’s death was announced in a statement on his official Facebook page.

“It is with great sadness we announce that on Feb. 9, Chick Corea passed away at the age of 79, from a rare form of cancer which was only discovered very recently,” wrote a statement attributed to Corea’s family.

Best known for his work with Return to Forever and with artists including Miles Davis, Gary Burton and longtime collaborator Stanley Clarke, Corea is responsible for essential jazz albums including “The Song of Singing,” “Return to Forever,” “Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy” as well as dozens of band recordings.

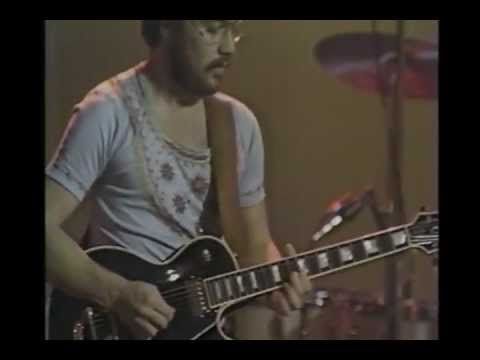

At the peak of his success, Corea was one of the most recognizable figures in jazz. With a thick head of black hair and trademark wire-rimmed glasses, starting in the 1970s he proved to be both a masterful technician capable of moving through gymnastic time shifts with the ease of an Olympian and a nuanced romanticist able to ease through lovely melodies.

Corea won 23 Grammy awards and was nominated 67 times. He was named a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master, considered the highest honor available to an American jazz musician, in 2006.

Supremes co-founder Mary Wilson, who died Tuesday at age 76, was the group’s linchpin and actively promoted their legacy long after their breakup.

The statement from the family also included a final message from Corea himself. “I want to thank all of those along my journey who have helped keep the music fires burning bright. It is my hope that those who have an inkling to play, write, perform or otherwise, do so. If not for yourself then for the rest of us. It’s not only that the world needs more artists, it’s also just a lot of fun.”

To his “amazing musician friends,” he wrote, “It has been a blessing and an honor learning from and playing with all of you. My mission has always been to bring the joy of creating anywhere I could, and to have done so with all the artists that I admire so dearly — this has been the richness of my life.”

Born Armando Anthony Corea on June 12, 1941, in Chelsea, Mass., the musician earned his nickname after it morphed from “Cheeky,” which an aunt used to call him. His trumpet-playing dad led a Dixieland band and regularly filled the household with jazz. Corea’s first instrument was a drum kit, but he gravitated to the more melodic percussion instrument, piano, soon thereafter.

Obviously gifted, after high school he moved to New York, where after brief stints studying music at both Columbia and Juilliard, he started gigging with Latin jazz artists Mongo Santamaría and Willie Bobo. By the mid-1960s he shifted focus to electric piano, where he beamed in on a tone using a waveform modulation process that produced a rich, distinctive signal. Over the next few years, he played on albums by artists including Stan Getz, Cal Tjader and Hubert Laws.

Corea signed to respected jazz and soul label Atlantic in 1968 and issued his solo debut, “Tones for Joan’s Bones,” on imprint Vortex that same year. His 1969 album “Is,” a crucial free-jazz document, found him aligning with players who would remain musically connected to him for years, including drummer Jack DeJohnette and bassist Dave Holland.

Corea earned his highest-profile gig to date when he joined trumpeter Davis’ band, starting on the 1968 album “Filles De Kilimanjaro.” That’s him opening “Bitches Brew” with a keyboard run that rings with distortion during Davis’ 1970 set of shows at the Fillmore West in San Francisco. Corea played on Davis’ crucial studio album of the same name.

In 1970 he also teamed with Holland and young horn and reed player Anthony Braxton to release music as Circle. “Return to Forever,” the keyboardist’s breakthrough solo album, came out in 1972 on ECM Records, a then-fledgling German label that would serve as an outlet for Corea’s more minimal recordings over the next decade. It was on “Return to Forever” that he hooked up with bassist Clarke and initiated a project that would reshape jazz.

Originally including vocalist Flora Purim, Return to Forever eventually gelled around a lineup of Corea, Clarke, guitarist Al Di Meola and percussionist Lenny White. That quartet, in various incarnations, became one of the most successful fusion bands of the decade. A subgenre built for expert players to flex their instrumental and rhythmic prowess, fusion featured tightly wound time signatures, slap-bass funk runs, electrified instrumentation and structures that could abruptly twist and turn.

Along with John McLaughlin‘s Mahavishnu Orchestra and Weather Report, Return to Forever propelled jazz back onto the commercial charts. Their 1974 album “Where Have I Known You Before” peaked at No. 32 on the Billboard charts. Their followup, “No Mystery,” earned Corea his first Grammy Award.

Return to Forever called it quits in 1977, and by that time Corea had relocated to Los Angeles. An avid reader, he’d become a fan of science fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard and joined Hubbard’s Scientology organization not long after. In another tax bracket due to his success, Corea eventually bought a mansion in Los Feliz that had a view of the Scientology Center on Sunset Boulevard. He adorned his home’s woodwork with decorative accents drawn from Scientology and played host to many group gatherings.

He remained an outspoken advocate for Scientology for the rest of his life and moved to the organization’s headquarters in Clearwater, Fla., more than two decades ago.

“My study of Scientology has also enabled me to write more music,” he said in a statement quoted on Scientology’s website. “I have become quicker and am able to use all of the musical abilities that I already have.”

In a 2019 short documentary video made by the organization, Corea explained his creative process: “I have never been that interested in being a soloist that is accompanied by others, where I am like feature guy and I am the one, but the game I like is where we become a union and everyone’s giving and taking and all creating the music.”

That love of communal creativity extended into the 1980s and 1990s through two complementary units: the Chick Corea Elektric Band and the Chick Corea Akoustic Band. Both earned Grammy nominations for Corea and landed at the top of Billboard’s jazz charts. Across his creative life, Corea was unapologetic about his popular success and how it related to his creative impulse.

“You can’t create in a vacuum and just fail to relate to people,” he told the late Times jazz critic Leonard Feather in a 1975 interview when asked about balancing his stylistic approaches. “At the same time, you cannot compromise your integrity. There has to be a middle road, where some sensible balance is made between, on the one hand, pure creation, and, on the other hand, the reality is that we live with, eating and survival and money and business.”

Citing artists as varied as Stevie Wonder, Andre Watts and Charlie Chaplin, all of whom succeed in what he called “that middle way,” Corea marveled at the way, for example, that the Marx Bros. could shift from slapstick to melodicism in a single edit: “Suddenly you saw Harpo alone, up in an attic, and for five minutes in this very commercial movie the whole plot was suspended while he just played the harp. It was beautiful.

“Art like that it’s just timeless,” he concluded. “That’s the paradox in the problem, the challenge that confronts every artist, and I hope I can always find that magic center ground in my own particular way.”

Corea is survived by his second wife, Gayle Moran; a son, Thaddeus; a daughter, Liana; and two grandchildren.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.