‘An unfinished masterpiece’: Revisiting Selena’s landmark crossover album, ‘Dreaming of You,’ at 25

“Growing up, I’d hear the same story every March, as if it were a holiday,” says Times Metro reporter Alejandra Reyes-Velarde. “My mom would say, ‘On March 31, 1995, I was chatting with friends in my hometown when a radio announcer somberly broke the news of Selena’s murder’.”

More than 25 years since her tragic death, the mythos of Tejana pop superstar Selena Quintanilla-Pérez remains as compelling as ever. This month, Netflix launched season one of “Selena: The Series,” a scripted drama based on the life of the young Mexican American singer.

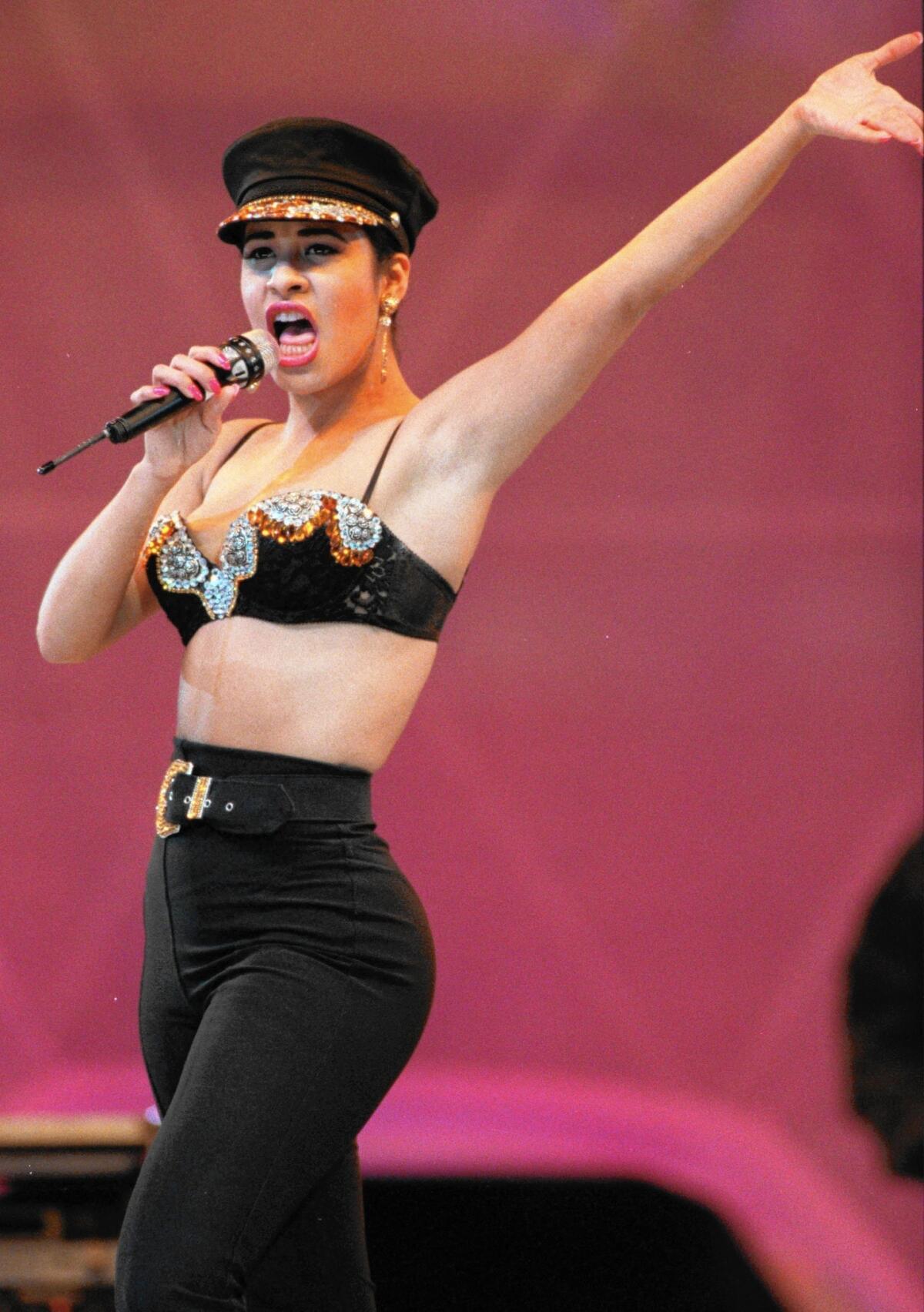

Executive produced by members of the Quintanilla family, the show follows the career of Corpus Christi-born Selena and the family band, Los Dinos, as they search for a deeper sense of belonging between American and Mexican cultures. Selena, played by Christian Serratos, is shown learning Spanish from cassette tapes to woo the Mexican music industry. It was after their performance at the 1989 Tejano Music Awards that José Behar, founder of EMI Latin, approached her band with a record deal — which her father-turned-manager, Abraham Quintanilla Jr., accepted on the condition that they would produce an English-language album. Titled “Dreaming of You,” the album would become Selena’s last; it was released on July 18, 1995, almost four months after she was shot dead by her fan club president, Yolanda Saldívar.

An inspired mix of original pop and R&B songs, posthumously interspersed with Los Dinos’ most popular Tejano and cumbia tracks, the album’s release was nothing short of historic. It was the first majority Spanish-language album to debut at the top of the Billboard 200; it would also become the best-selling album in Latin music for the next two decades. Its positive reception, heightened by the tragedy of Selena’s death, became a testament to Latin music’s market viability in the United States, paving the way for Ricky Martin and Shakira to stake their claim in American pop.

In light of the new series, four Latinx contributors at The Times revisited the album, as well as their own memories of Selena. Fidel Martinez, audience engagement editor, once saw Selena perform a free concert in Reynosa, Tamaulipas in 1993. Upon hearing of Selena’s death in 1995, staff writer Daniel Hernandez mourned with classmates in his San Diego high school, while music reporter Suzy Exposito, then 5 years old, began learning Selena’s songs from the radio. Reyes-Velarde, born three weeks after Selena’s death, knew the singer best from Jennifer Lopez’s portrayal in the 1997 biopic, “Selena.”

“After so many tributes in TV and film,” says Reyes-Velarde, “I wondered from a young age: Why were we still talking about Selena?”

Exposito: In both the 1997 movie and the 2020 show, we see how much Selena — like many Latinos born and/or raised in the U.S. — struggled with living in the liminal space between American and Mexican cultures. Despite being in a Tejano band, Selena modeled herself after R&B stars like Jody Watley, Paula Abdul and Janet Jackson. And she finally got the leeway to make the kind of music she wanted to with “Dreaming of You.” Do you feel like her personality came through more when she sang in English?

Hernandez: I know this album is referred to as the crossover, but listening to it again makes me ask: “crossover” for who? Selena still leaned on mariachi and cumbia sounds, so in a sense, this “crossover album” is really for the legions of English-speaking American listeners who were poised to become her next wave of biggest fans. Twenty-five years later, “Dreaming of You” sounds like an entry point of traditional Latin or Mexican music genres for people who might otherwise never have given this music a chance. To me that group includes Americanized, or acculturated first and second-generation children of immigrants — the people most identified as her core audience today.

“Selena: The Series” turns the focus to the men behind her — creating a self-serving, controlled narrative that fails to illuminate the late singer herself.

Reyes-Velarde: My mom, who immigrated from Mexico in 1995, recalls Selena as very much an American artist who learned Spanish to capture a lucrative audience. So for a long time, I believed she was an English-to-Spanish crossover artist — not the other way around!

Hernandez: There is nothing more “American” than R&B and rock ‘n’ roll! So it made perfect sense for Selena to segue into pop and R&B. It’s all we were listening to back then: SWV, Mary J. Blige, Mariah Carey and Janet Jackson.

Martinez: The thread running through the album is Selena’s willingness to experiment with different genres and largely succeeding at it. She did this in Spanish — dabbling in cumbia, Tejano, corridos and mariachi, and injecting them with electronic and pop elements.

Exposito: “Donde Quiera Que Estés” with Barrio Boyz was an excellent new jack swing fusion. And just listen to that dancehall influence in the 1995 remix of “Techno Cumbia” — Selena was already on that reggaetón tip! I’m being a little facetious here, but one of her superpowers as an artist was how prophetic she was. She was consistently on the pulse of what was happening, not just in Tejano or Anglo-American music.

Martinez: It’s really hard to think of this album as anything other than an unfinished masterpiece, one which makes the listener fill out the missing part of its canvas with their own interpretation of who Selena was and what her legacy is. Only a handful of these songs were originally recorded before she was murdered, and it’s really hard to say what Selena singing in English would actually look like from this small, albeit great sample.

Exposito: “Dreaming of You” was the song that Selena was begging to do from the time she was a kid. We saw how much she wanted this in the Netflix series — her dad pushing EMI Latin to let Los Dinos put out an English album.

Hernandez: It’s a perfect song. When you listen to the audio liner notes that accompany the record on Spotify, it’s clear that “Dreaming of You” was her song, she really loved it, and recorded it with a fullness of conviction and devotion that shines through. It is just crushing, thinking about how this song bookends the 1997 biopic, and almost tells the story of her entire life. We’re all “dreaming of” Selena. I’m triste.

It was the year Latinas took over the Super Bowl, and Bad Bunny — like everyone in quarantine — twerked alone.

Martinez: I think it’s hilarious when her brother, A.B. Quintanilla, says he didn’t initially like this song, which just goes to show you that, as pivotal a role as he played in shaping Selena’s music, he didn’t define her sound. “Dreaming of You” is as peak Selena as “Como la Flor.” And “God’s Child (Baila Conmigo),” which featured David Byrne, is wholly something else.

Exposito: David Byrne explained on a recent Apple Music special that they wrote “God’s Child” together for the movie “Don Juan DeMarco,” starring Johnny Depp and Marlon Brando — but the producers never used the track, so it went on “Dreaming of You.” He’s also said it was the last song Selena recorded before she was murdered.

Martinez: This album was supposed to be her first foray into the so-called American mainstream, and what does Selena Quintanilla-Perez do? She records a track with the dude from the Talking Heads, an artist whose other notable collaborators include Brian Eno. “God’s Child (Baila Conmigo)” sounds like a hypnotic chant that just sucks you in. It might be the most mainstream track that David Byrne has ever been a part of, and he has a Mexican American to thank for that.

Reyes-Velarde: A song that stands out to me is “Tu, Solo Tu.” Selena sings: “Mira cómo ando mi amor por tu querer/Borracha y apasionada, nomás por tu amor.” It’s the type of lyric I hear in corridos about drinking your sorrows away, but they are almost always sung by men. To me this song is a reminder that she broke many barriers for women in music.

Exposito: Lorraine Ali reviewed the new Netflix series in The Times — she critiqued the portrayal of Selena, saying it was missing her voice. How do we feel about this assessment of the show?

Hernandez: I think Lorraine is spot on. Selena the character definitely feels like a peg in an ensemble and not the lead; it would have been more accurate to call the show “The Quintanillas.” Having said that, there are some truly moving moments in the series, and the majority of the writers in the room were women.

Reyes-Velarde: The show is basically about the Quintanilla men… and somehow still bears Selena’s name. It’s disappointing to see how many of Selena’s scenes focus on her appearance. So many interviewers used to comment on her appearance and Selena was obviously not into it. In one interview, she’s asked whether her husband ever got jealous because of the way she dressed, and why she doesn’t like it when people say she’s “sexy.” Selena says, simply, “I don’t think of myself that way.” She was a successful businesswoman at 23, defending herself in Spanish TV interviews while still learning the language and navigating her new fame. I want to see a show about all of that.

Hernandez: I know people have been making fun of the wigs, but that’s how hair looked in the late ’80s and early ’90s — don’t be fooled! The house setting is perfectly ’80s, U.S. Latino middle-class coziness, down to the cereal boxes and the clothing. I’ve seen worse, kitschier versions of the ’80s in many television shows, and this one is expertly done.

Martinez: Any retelling of Selena’s story is bound to be flawed, if only for the fact that the Quintanilla family was involved in the production of the Netflix series. What were people expecting? That Abraham and Co. would sign off on a story that offered nuance and depth at the risk of taking Selena down from the altar they’ve built, and we’ve all worshipped at?

Exposito: Selena really is the closest thing U.S. Latinos have to a saint, or better yet, a Marvel superhero. There have been 23 posthumous compilations, box sets, live albums and soundtracks released since Selena’s death — the latest being the music from the Netflix series. Is it time to put her brand and her spirit to rest?

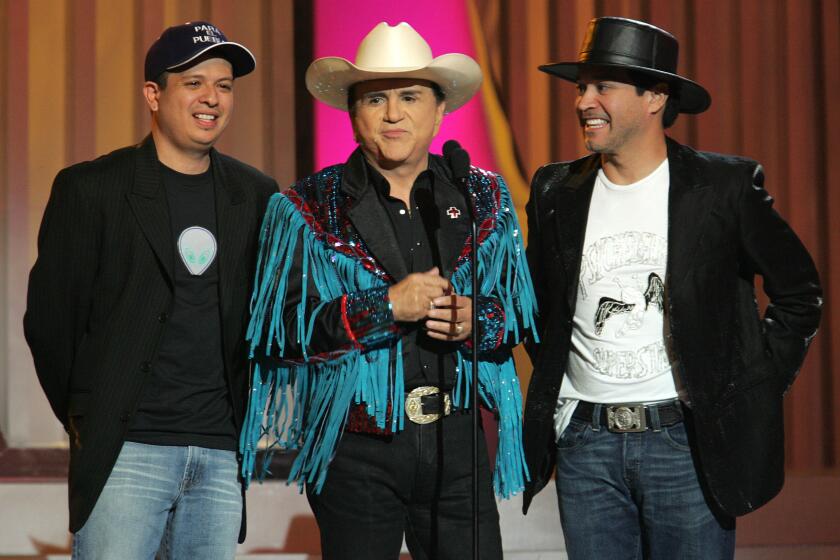

“The Johnny Canales Show” was a mainstay of Spanish-language TV in America, launching the careers of countless Tejano, conjunto and norteño music stars.

Martinez: Yes — but only if this moratorium on obvious cash grabs is extended to the likes of the Beatles, Elvis, Tupac and the Notorious B.I.G.

Hernandez: Although I welcome the efforts intended to introduce new generations to her music and her persona, there has to be a respite at some point, no? The fact is the tragic loss of Selena can only recycle so many times before it starts feeling exploitative.

Reyes-Velarde: Before watching the Netflix series, I would have said yes, it’s time to take a break from Selena. But the series left me craving another retelling of her story, without the family controlling the narrative. I hope that doesn’t cloud our ability to recognize new Latina superstars, though.

Hernandez: That’s an excellent point, Alejandra. What this idea also makes me wonder is: Where are the next Selenas? Are there no other Chicana artists who can appeal to a broad range of audiences? Becky G is the first that comes to mind, but can anyone come close to Selena? I think the industry, and the culture at large, should ask themselves why “new Selenas” haven’t emerged in the last quarter-century.

Reyes-Velarde: I’m fascinated by just how present Selena has been throughout the lives of millennials like me who were born after her death. Whether or not you love her music, she remains such a huge part of Mexican American, and by extension, Latinx culture.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.