James Cameron’s old comments prompt Native American boycott of new ‘Avatar’ sequel

If you haven’t seen “Avatar: The Way of Water” yet, a social media campaign led by Native Americans hopes it’ll stay that way.

After the premiere of the long-delayed “Avatar” sequel, a renewed campaign is calling on would-be viewers to boycott the sci-fi film, which has already grossed more than $300 million internationally.

“Join Natives & other Indigenous groups around the world in boycotting this horrible & racist film,” Yuè Begay, a Navajo artist and co-chair of Indigenous Pride Los Angeles who is behind the campaign’s resurgence, wrote in a tweet that has been liked by more than 40,000 users. “Our cultures were appropriated in a harmful manner to satisfy some [white flag emoji] man’s savior complex.”

While James Cameron’s ‘Avatar: The Way of Water’ dominated the weekend box office, it remains to be seen whether the film will prove a true success.

The Native American movement to boycott “Avatar” sprang up after the first film’s release in 2009. But calls to skip the franchise found new life in recent weeks with resurfaced comments made by the film’s director, James Cameron, in 2010 about the Sioux nation, including the Lakota people, which the campaign calls “anti-indigenous rhetoric.”

In 2010, the Guardian wrote about Cameron’s efforts to oppose the Belo Monte hydroelectric dam, which eventually led to the displacement of Indigenous people living in the Amazon. In the article, the Oscar-winning director said his time spent with the Amazon tribes led him to reflect on the history of Indigenous people in North America. Cameron credited Native American history as the “driving force” behind writing the script for the 2009 “Avatar” film.

“I felt like I was 130 years back in time watching what the Lakota Sioux might have been saying at a point when they were being pushed and they were being killed and they were being asked to displace and they were being given some form of compensation,” Cameron told the Guardian.

“This was a driving force for me in the writing of ‘Avatar’ — I couldn’t help but think that if they [the Lakota Sioux] had had a time-window and they could see the future … and they could see their kids committing suicide at the highest suicide rates in the nation … because they were hopeless and they were a dead-end society — which is what is happening now — they would have fought a lot harder.”

Representatives for Cameron were not immediately available for comment Monday.

Thirteen years after the first ‘Avatar,’ James Cameron finally returns to the distant moon of Pandora in this transporting, radiantly personal sequel.

The original “Avatar” film focuses on a human solider, Jake Sully (Sam Worthington), who is sent by resource-hungry colonists from Earth to infiltrate the Na’vi people, but he eventually sympathizes with them and becomes a Na’vi himself. He fights off the colonizing forces from Earth, but the Na’vi are still displaced from their home.

“The Way of Water” takes place more than a decade after the events of the first film and follows Sully family members after they have fled their land-bound home for a new oceanic one, where their conflict with the invading earthlings continues.

Cameron has long been clear that “Avatar” is a fictional retelling of the history of North and South America in the early Colonial period, “with all its conflict and bloodshed between the military aggressors from Europe and the indigenous peoples,” according to a Business Insider report. The report cited court filings from 2012. Cameron has faced lawsuits from many who allege he stole their film ideas.

“Europe equals Earth,” he wrote. “The Native Americans are the Na’vi. It’s not meant to be subtle.”

Cameron’s offending comments were resurfaced last week by Johnnie Jae, an Otoe-Missouria and Choctaw artist living in Los Angeles. The remarks, which were largely overlooked a decade ago, drew intense backlash on social media from some Native Americans who specifically took issue with the implication that Native people could have “fought a lot harder” to avoid displacement and genocide.

“James Cameron apparently made Avatar to inspire all my dead ancestors to ‘fight harder,’” wrote Johanna Brewer, a computer science professor at Smith College. “Eff right off with that savior complex, bud.”

“Eww, way to victim blame & not reflect on your own positionally/ privilege,” wrote Lydia Jennings, of the Wixárika and Yoeme people. “Saw original avatar; was annoyed people celebrated the story while not reflecting on how many Indigenous Nations in the present are fighting to do so.”

How free divers, tech experts and dauntless actors helped James Cameron redefine underwater photography with ‘Avatar: The Way of Water.’

Brett Chapman, a Native American civil rights attorney, called “Avatar” a “White savior story at its core” in a tweet decrying Cameron’s comments.

“I won’t be seeing the new one,” Chapman wrote. “It does nothing for Native Americans but suck oxygen for itself at our expense.”

Native American TV writer Kelly Lynne D’Angelo, who has written episodes of Netflix’s “Spirit Rangers,” suggested people could “donate the avatar money to Native communities,” instead of watching the film. “You took our land, then our children, then our skin,” she wrote. “Can’t you see this is *still* manifest destiny in action?”

Autumn Asher BlackDeer, a social work professor at the University of Denver who is of the Southern Cheyenne Nation, responded to the comments by compiling a list of movies by Indigenous filmmakers for those who “don’t wanna watch the colonial glorifying blue people movie.”

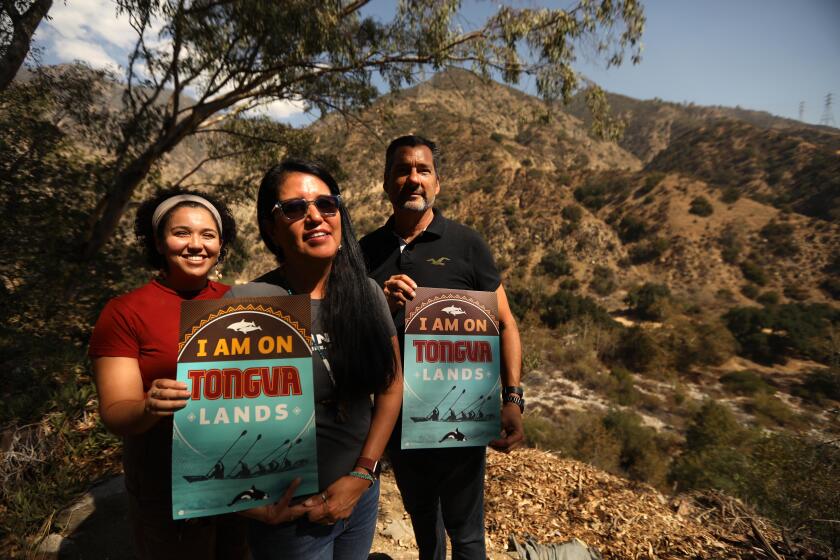

A one-acre property tucked within a canopy of oak trees and shrubs in Altadena has been transferred to Los Angeles’ first people.

The boycott campaign also zoomed in on Cameron’s decision to cast white actors as leads to play the Na’vi, an indigenous people in the film’s fictional Pandora, which Cameron previously said were based on Indigenous cultures across the globe.

The campaign called such creative decisions “blueface,” in the tradition of the racist performance practices of “redface, blackface, yellowface.” Blueface refers to when a creator appropriates nonwhite cultures to create a fictional world with characters who are mostly played by white actors, the campaign said. These creative decisions, the campaign said, invalidate the experiences of actual Black, Indigenous or other marginalized people of color.

“We should’ve been the ones whose faces and voices appeared onto the screen,” Begay wrote in an open letter to Cameron. “We are the experts in portraying our hurt, suffering, and more importantly, our resilience.”

“White people being aliens based on actual indigenous people,” the letter continued, is “actual colonialism.”

When a coveted ranch on the most pristine river in California was suddenly up for sale, a shocking history — and a massacre — bubbled to the surface.

Chapman, who is a citizen of the Pawnee nation and also of Ponca and Kiowa heritage, has been a part of tribal sovereignty cases in Oklahoma and has long protested stereotypical portrayals of Native Americans.

He told The Times that renewed criticism of the film franchise showed the progress made in the fight for racial justice since Cameron’s 2010 comments. Yet he recognized the continued negative impact films such as “Avatar” could have on people’s understanding of Native American history.

He called Cameron’s “Avatar” films a “whitewashing of history to let everybody feel good about themselves.”

“At the end of the day, he’s not exploring anti-imperialist, anti-colonial themes,” Chapman said, “he’s making movies to make money.”

He pointed at the film’s use of tribal tattoos, characters with dreadlocks and warrior-culture elements used in the film’s portrayal of the Na’vi.

“They’re taking all these tropes with the white gaze, putting it in outer space, making them blue and not human,” Chapman said. “But Native people are real-life people here on Earth.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.