DEL NORTE COUNTY, Calif. — Here in this forgotten corner of coastal California, nestled amid a curtain of redwoods so far north it feels otherworldly, the state’s most pristine river harbors more than a century of secrets.

Its emerald-green water once flowed red with Native American blood, its wetlands haunted by one of the largest massacres in U.S. history. Today, the Smith River is the last major waterway in California that runs freely without a single dam — a precious refuge for salmon, for steelhead and a bygone timber community still searching for a future.

Settlers came here for the gold, and then the trees, but this river is the true lifeline for Del Norte County, a coastal California outlier where farmers now call the shots and environmentalists are met with disdain. The politics lean red, and many here are inclined to secede from a state where most would pronounce Norte as “nor-tay.” (It’s “nort.”)

“My whole life, I grew up hearing there’s no law north of the Klamath,” one resident said. “It’s like the Wild West out here.”

And for more than six generations, one family has held the keys to this exhausted frontier: 1,668 acres of pastureland right by the river mouth, where clear, cold water winds its way from the Siskiyou Mountains to the sea. Known as Reservation Ranch, this coveted property has been off limits to most, deforested and quietly altered over the years by a system of levees, pumps and wetlands packed with discarded waste and dead cattle.

So when Reservation Ranch suddenly went up for sale, chaos ensued. Conservationists have sought for years to restore this final piece of the river, and the owners, shoved into the spotlight, are now facing the full force of state regulators who rarely make it this far north. Rumors exploded as fellow farmers met privately to rally against the demise of yet another livelihood.

The Tolowa Dee-ni’, decimated then sidelined for more than 150 years, have also joined the fray with a bold plea to be reunited with the land — an appeal that shocked many in this mostly white community.

This collision of interests now coming to a head at Reservation Ranch strikes at the heart of an uncomfortable truth: California, like the great American West, was largely built on violence — violence to not just the land, but also the native people of the land.

::

Before Jedediah Smith, an American frontiersman who arrived in the 1820s, this land of redwoods, spruce and serpentine was known as Yan’-daa-k’vt.

For centuries, Tolowa people lived in balance with the elk that roamed free, the smelt that returned each summer and the thousands of Aleutian geese that once fanned across the forested coast. They stewarded this land through complex laws and time-honored stories. They had a name for every riffle in the river.

Then the Natlh-mii~-t’i, the knife-brandishing white man, arrived and ran them to near-extinction. Today, the Tolowa are largely unknown.

One tribal leader recalls how her son’s third-grade class could choose a Native American tribe to study. When his teacher handed him a list, he saw Navajo and Cherokee but not his own people.

“What about the Tolowa?” he asked. His teacher had never heard of them.

It wasn’t until Loren Me’-lash-ne Bommelyn, a culture bearer for the Tolowa Dee-ni’, started documenting the language with elders that he unearthed horrifying details of a not-so-distant past.

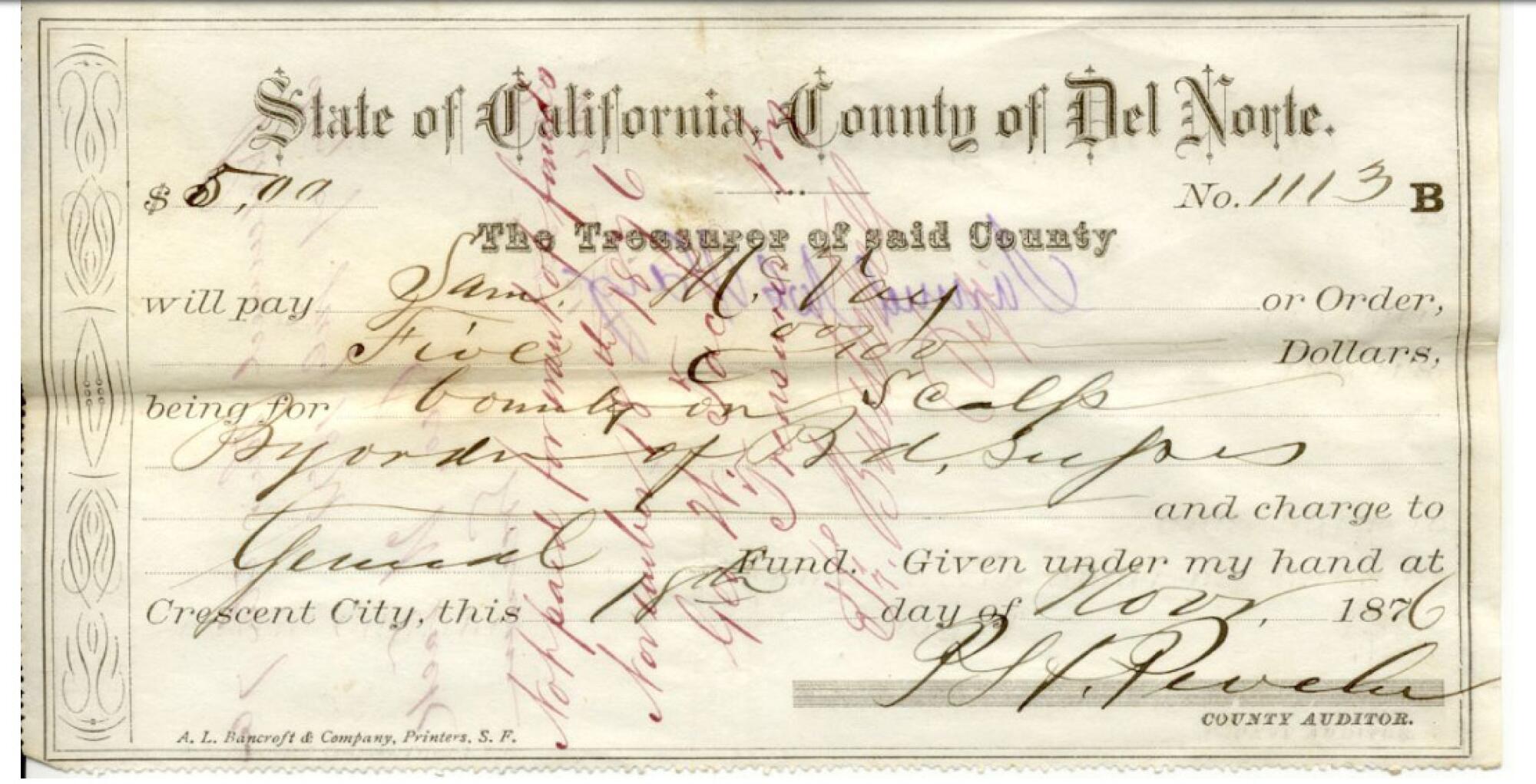

There were government-sanctioned bounties beginning in the 1850s that awarded those who brought in Native American scalps — one receipt showed a payment of $5, Bommelyn discovered. Then in the winter of 1853, while hundreds of Tolowa people gathered for their world renewal ceremony, local militia swarmed Yontocket.

They slaughtered the villagers. Lit everything afire.

“The flames of the burning houses reached higher as even the babies were thrown to their deaths,” said Bommelyn, who wove in and out of fluent Tolowa as he spoke. So many bodies were burned or tossed into the river that no one could do a complete count.

White sources put the death tally at about 70 to 150 people. Tolowa accounts put it closer to 450, perhaps even 600.

“Even if we halve the latter estimate, Yontocket may rank among the most lethal of all massacres in U.S. history,” wrote Benjamin Madley, a historian of Native America at UCLA, in his book “An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe.” “Yet, it remains unknown except to a few scholars, locals, and of course, the Tolowa.”

It was a time shaped by the words of Peter Burnett, the first governor of California, who declared in 1851 that “a war of extermination will continue to be waged … until the Indian race becomes extinct.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

As the Gold Rush continued to draw fortune seekers to Del Norte, the Tolowa suffered systematic attacks and imprisonment; their children were taken away. Within a span of five years, their population was reduced from as many as 5,000 to no more than 900, Madley said.

By 1862, an agreement finally allowed for the establishment of a roughly 40,000-acre reservation that included Yontocket. But this peace lasted barely six years: The Tolowa were shoved into concentration camps in 1868 and their land, right by the river mouth and prized along the coastal plain, went up for grabs to any qualified white man.

Enter Heine “Henry” Westbrook, who ended up with the parcels where the reservation headquarters once stood. By the mid-1900s, the Westbrooks had become local royalty. Celebrated as hardworking outdoorsmen who pulled themselves up by the bootstraps, Henry “Hank” Westbrook III and his brother “Chopper” worked the land and tamed the wetlands as they transformed the family operation into pioneering ventures that included timber, dairy, Easter lily bulbs, a seaside resort and even the first privately run fish hatchery in California.

The ranchers altered the estuary as they dredged and blocked the channels, pumped and rerouted water for irrigation and even dumped manure (and dead cattle) into the river, according to multiple state and federal agencies. An estimated 40% of the original wetland has been diked, drained or destroyed. These violations — which could add up to millions of dollars in fines, as well as restoration orders — are now being duked out with the Westbrooks.

Through it all, the Tolowa watched the center of their world deteriorate. Life withered along the riverbank. Water vanished. Lonely redwood stumps remained where the tallest trees in the world once stood.

Then in the latest twist of fate, the ranch last year was suddenly put up for sale. For the first time in more than 150 years, somebody new — somebody with $12.95 million — could own this critical piece of the river.

The Tolowa Dee-ni’ — today a federally recognized nation with roughly 1,800 members — lacked the money to buy the property outright. They tried at first to raise the funds with a public call for help, but those hopes were quickly crushed as other interested buyers rushed in. State regulators made it clear that regardless of who owns the ranch, the environmental violations must be resolved.

Tribal leaders are now running up against what some call green colonialism: Left out of the sudden flurry of high-level negotiations over the future of Reservation Ranch, they have been scrambling to figure out the bureaucratic maze of California land management. Each local, state and federal agency seems to be in charge of a compartmentalized zone of land, river, coast — a baffling, fragmented way to oversee a place that, to the Tolowa Dee-ni’, is all interconnected.

In an almost two-hour discussion with a Times reporter, the tribal council explained that what they want, at the very least, is to be included in any restoration plans. Too often, they said, the council finds out about a land-trust deal or management strategy after everything has already been decided. Looping in the Tolowa Dee-ni’ often feels like a box that gets checked at the very end of the planning process.

Standing in a field of reed canary grass, not far from where Yontocket once thrived, Scott Sullivan, the tribal vice chairperson, reflected on how the health of his people and the health of this river valley are one and the same.

He pointed to a cluster of willows just out of reach. For his whole life, Reservation Ranch has been right there.

“No matter who the new owner ends up being, this is still the center of our world,” Sullivan said. “We want to work with every agency to ensure that the restoration that needs to be done, will be done. We are not abdicating from our responsibility to steward the land.”

There’s no word in Tolowa for land “management” or control. There’s just shu’-nelh-‘i~. To care for the land.

::

When the conservation world first got word that Reservation Ranch was for sale, the excitement was electric. Many called the obvious guy: Grant Werschkull.

Werschkull, who co-leads the nonprofit Smith River Alliance, has coordinated numerous efforts over the years to acquire properties that could then be put into the care of public agencies such as the U.S. Forest Service, California State Parks and the Department of Fish and Wildlife.

His team made an offer immediately.

In a state where most rivers are now choked by dams and where mass fish die-offs have become increasingly routine, the Smith serves as a final stronghold for California’s vanishing salmon, steelhead and cutthroat trout. Born in freshwater streams, these anadromous fish rely on a complicated journey down the river, through the estuary and finally out into the ocean. The population survives only if enough make it back upstream to lay and fertilize eggs.

This unique life cycle weaves together the needs of fresh and saltwater ecosystems. The returning fish bring nutrients back from the ocean — feeding the wildlife along the river, which then distribute their remains throughout the forest. Without salmon, life along the entire watershed starts to unravel.

On a clear Wednesday afternoon, months after putting in his bid, Werschkull marveled at the old-growth forests still standing along the south fork of the river. He has a story for every tributary of the Smith and can recite all the riparian species that mark a healthy riverbank.

“Take a look at this,” he said, unfurling a large, color-coded parcel map. White squares indicated private land. Green, public. Highlighted in pink, yellow and blue were hard-fought acquisitions from the timber companies.

There was the 25,000-acre Mill Creek acquisition that cost $60 million. Then the 9,500 acres at the mouth of Goose Creek. He proudly pointed to the most recent victory — 5,400 acres along Hurdygurdy Creek, which a developer had tried to buy and turn into subdivisions. This deal took almost 10 years to complete.

A former consultant for fish and wildlife officials, Werschkull brings a seasoned touch to the politics of funding and environmental bureaucracy. Considered a power broker in town, he and his team have hammered out complex transactions and forged ambitious collaborations to ensure the Smith remains one of the most pristine — perhaps the most pristine — river in the country.

Restoring the river mouth is the last piece to the equation. The estuary — gated and degraded by decades of dairy farming — is home to at least 38 fish species, as well as red-legged frogs, bank swallows and waterfowl. State wildlife officials note that on Reservation Ranch alone, there are three major tributaries and two critical staging holes for salmon migration.

Werschkull and his team have spent years knocking on doors and negotiating win-win agreements with property owners — fixing a broken culvert, for example, that would help fish passage as well as the farm. On Reservation Ranch, they finally have a project in the works to restore an area known as Delilah Creek.

These efforts to play nice with everybody, including ranchers, have stirred occasional suspicions. It’s not easy being a conservationist in Del Norte, where many would rather put the land to economic use. Relations have also been strained at times with tribal leaders, who challenge the notion of an untouched wilderness. It doesn’t help that the public agencies tasked with maintaining this wilderness are often underfunded.

Werschkull sighed. Since Smith River Alliance first put in its offer, the jostling for Reservation Ranch has taken quite a few turns. In a county where he needs to remain collegial with everybody, Werschkull’s choosing to step back for now. Perhaps there’ll be a chance later to weigh in.

He pulled over to a spring by the river where he knew the water was particularly sweet. He took a sip, gathering his thoughts as he considered what to say next.

“I just want what’s best and most efficient for the river,” he said. “It remains to be seen who will be involved in a lead role, and I certainly hope it’s a team of very capable people with a good restoration focus.”

::

There’s a bitter saying in this old timber community that not one more acre of private land should become public. More than 80% of the land today in Del Norte County has come under state or federal control — mostly as parks, national forests or wildlife preserves.

“Our fishing fleets have been reduced to nothing, our timber grounds have literally been reduced to nothing, and we’ve got what’s left of a dairy industry here barely hanging on,” said Chris Howard, chair of the county Board of Supervisors. “When you’ve got people sitting at home making nothing and trying to figure out where their next meal is coming from — you create a community that’s very resentful.”

Sitting on the riverbank at Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park, Howard recalled arriving in Del Norte in the 1990s as the last sawmill shut down. Three hundred and fifty people lost their jobs. The tourism industry never became the economic savior that state and federal officials had promised. Young people — the ones who make it out of Del Norte — don’t come back.

Howard gazed across the water and pointed to a towering grove of redwoods.

“Those trees don’t pay the taxes,” he said. He points to another cluster. “Those trees aren’t paying for our roads to stay open.”

A zoologist by training, Howard’s first job was to study spotted owls for the timber industry. But with logging on its way out and so many neighbors without jobs, Howard found himself trimming his hippie-length hair and devoting more energy to the community’s economic plight.

He’s since led the Chamber of Commerce and served on numerous boards — he even oversaw economic development for Elk Valley Rancheria, a smaller tribal nation near Crescent City. Most recently, he’s been working with Alexandre Family Farm, a growing and influential dairy operation touted for its regenerative and organic practices.

Critics say he’s become a walking conflict of interest. Others say it’s hard not to be in such a small world.

Howard was cautious while speaking to a reporter from a big liberal city and painfully aware that everybody knows everybody in town. He’s tired of having yet another issue explode in a community that cannot afford to be further divided. He’s tired of big government swooping in from Sacramento, telling people here what is best.

With Reservation Ranch, he’s been trying to facilitate some kind of truce between the state and the Westbrooks. He personally would like to see agriculture remain on the land.

“I think you can have a viable agricultural operation there and still have fish swimming up and down those creeks in massive numbers. It can be done,” he said. “That would be a benefit for everybody, no matter who owned it.”

As for the Westbrooks, it hasn’t been easy ending what the family started generations ago.

When reached by The Times after a day of moving cows, Bobby Westbrook sighed and said the reason why he and his brother Steven were selling the ranch was simple: “None of our kids want to come home and run the ranch like we have.”

He called many of the allegations nonsense. Regarding some of the state violations, he and his brother did agree to move the manure out of the estuary and work it into the land as fertilizer. They’ve also agreed to dispose of a wood debris pile that had accumulated for about a decade and conduct a fish passage study on four key sections along the estuary.

The sale is in limbo until the remaining violations get resolved. For now, Westbrook said they’ve leased the ranch to the Alexandre family. He and his brother want to make sure their staff still have jobs when they move on.

“Our heart is to sell the ranch to someone who would keep the land in agriculture. We employ quite a few people who have families to support,” he said. “It is very meaningful to us that the land goes to the right people.”

::

For the Tolowa Dee-ni’, playing ball in such a small community has also been strange. Bommelyn, the culture bearer, said his great-grandmother Delilah was the midwife who delivered Hank and Chopper Westbrook. (Yes, the same Delilah of Delilah Creek, the portion of the estuary that Werschkull has been working with the Westbrooks to restore.)

Some tribal members have worked for, and with, the Westbrooks. Everybody’s kids seem to play on the same sports teams at school. For years, the Westbrooks and tribal leaders even sat together on the board of the local fish hatchery.

The Westbrooks have also sold them land in the past — though whether they were fair deals is up for debate. Their 65-acre Ship Ashore resort, previously home to a major village known as Xaa-wan’-k’wvt (Howonquet), turned out to be a mess of hazardous waste and building code violations. Tribal staff ended up shutting things down and seeking help from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which agreed the site was unsafe.

Some in town saw the shuttered hotel as Del Norte once again losing jobs and land. Tribal staff clarified that they plan to reopen the site once they’ve cleaned up the contamination.

They understand the resentment that the Tolowa Dee-ni’ nation seems to be yet another government taking away land. But this fear is misguided, they say. Yes, they’ve cobbled together funding over the years to reclaim parts of their ancestral territory — but all told, the tribal nation today owns less than 960 acres, 875 of which they pay local taxes on like everybody else.

No group in Del Norte has the money to take on a property as large as Reservation Ranch. The future of the estuary relies on everyone understanding the benefit of working together.

“There are good jobs that can be had there,” said Tom Wheeler, executive director of the Environmental Protection Information Center, a grass-roots group that has been advocating for a solution that reunites the Tolowa with the land. “I would hope we could start to recognize that the restoration economy is a good one for Del Norte County to embrace and develop — and not view as necessarily hostile to its existing agricultural and timber community.”

Ultimately, California — with its many environmental protection agencies and conservation groups — still needs to figure out where a sovereign tribe and a languishing rural community fit into this ecosystem of co-stewardship.

“We need a paradigm shift,” said Wade Crowfoot, who oversees the state’s management of natural resources and has been developing ways to work better with tribal nations. “The modern conservation movement that catalyzed around Earth Day created this perception that environmental protection is protecting nature from people … but people have always been part of nature.”

::

On a late-afternoon hike near a coastal lagoon known as Lake Earl, just south of Yontocket, Sandra Jerabek ruminated on how much the land, and its people, still need healing.

These ancient wetlands had been plundered for timber, then ranched, and finally acquired by the state in the 1970s to nurture back to life. Few know that this nature preserve is also the site of another massacre that took place a year after the first one in 1853.

Tolowa people had gathered here at ‘Ee-chuu-le’, another prominent village, after their main village burned down. But on New Year’s Eve, local militia once again torched the Tolowa’s plank houses as they slept — and killed those who came running out.

Some tried to hide in the lagoon and were shot when they came up for air. All told, seven layers of bodies were stacked and burned.

“I always felt like it was our duty to educate the community,” said Jerabek, clutching a history book she had scribbled with notes. “As much as I love living here, there’s a strange disconnect and fragmentation because there has never been a public airing of what happened here.”

Jerabek, who co-founded the volunteer group Tolowa Dunes Stewards, has spent the last two decades doing much of the work that state parks and wildlife officials never had enough funding to do: pull out invasive plants, make park signs, work side by side with the Tolowa.

A marsh wren trilled in the distance as Jerabek pondered the future. She stooped down and to her delight, uncovered a tiny yellow wallflower.

For years, her volunteers have pulled out, root by root, an overwhelming amount of European beachgrass that carpeted the coast. Now this rare flower, believed to be found only in this far-flung corner of California, finally has space again to grow.

The plant had been displaced for so long that it needed a new name. Jerabek knew just what to call all this renewed color emerging from the land.

She named the flower the Tolowa Coast Wallflower, after the people who have been here all along.