‘This is my pantheon’: Tour Spike Lee’s Academy Museum exhibit with the man himself

The unmistakable voice boomed through the quiet galleries of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures: “Look at this! Two GOATs together, side by side!”

The source of the declaration was eyeing two massive framed photos of Muhammad Ali and Michael Jordan in action.

“GOAT!” he said, pointing to Ali and using the acronym for “greatest of all time.” “GOAT!” he repeated, pointing to Jordan with a mischievous smile. “Not LeBron! Not LeBron!”

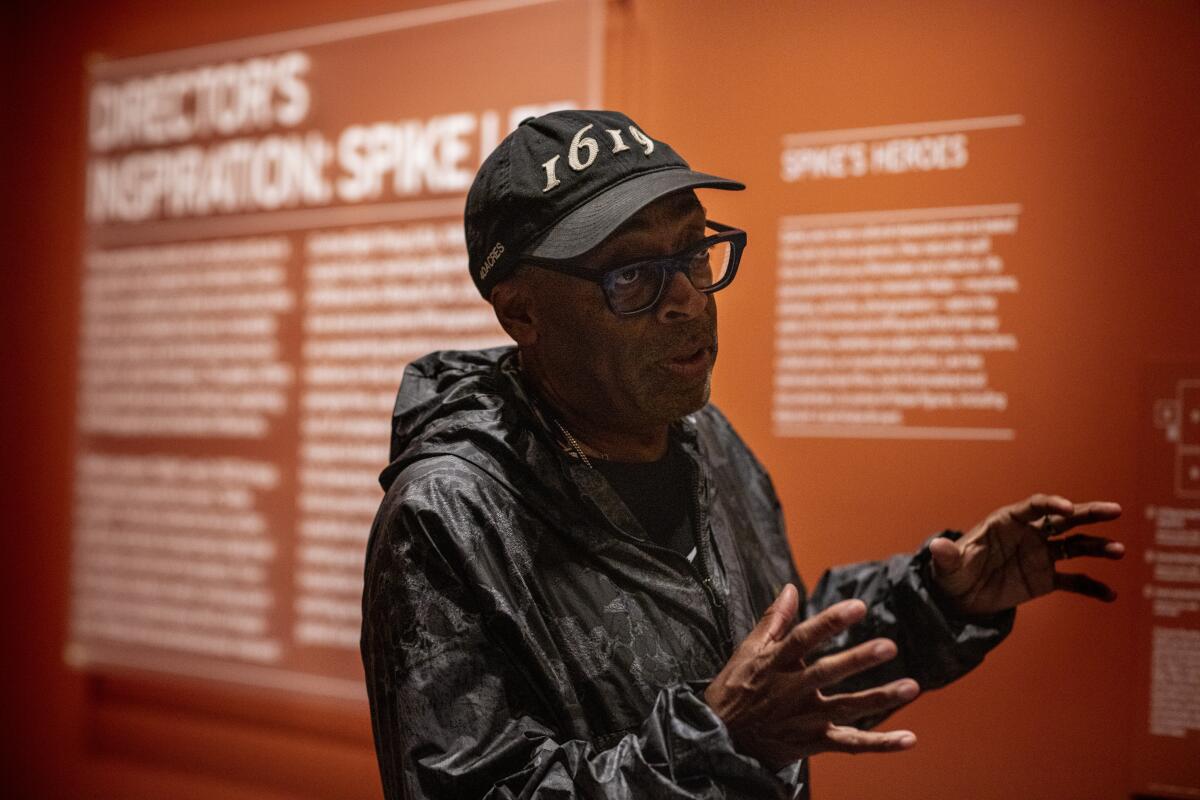

Spike Lee was in da house — or, more specifically, da museum.

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The writer-director-producer, who ranks among the most prominent and influential filmmakers of modern cinema, was in town last Friday to preview the gallery focused on him, his heroes and his inspirations, which will be a centerpiece of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ new museum dedicated to the craft and art of film. The huge photos — both signed by the legendary athletes — were just a few of the items featured in the gallery.

Visitors will be able to trace Lee’s career through props and memorabilia dating back to his 1983 award-winning student film “Joe’s Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads,” moving through his features (“Malcolm X,” “Do the Right Thing,” “School Daze,” “Jungle Fever,” “Bamboozled” and his most recent, “Da 5 Bloods”), documentaries (“4 Little Girls”) and his two Oscars — one honorary and one for his adapted screenplay for “BlacKkKlansman”).

“I’m elated,” said Lee. “I’m happy and honored that this exhibition is here for the opening of the museum.”

The rutted road to the Academy Museum’s long-awaited premiere was marked by behind-the-scenes infighting, financial woes, ousted leaders and a racial reckoning.

Far beyond an examination of Lee’s provocative, often controversial projects, the gallery is an eye-filling, emotional journey into the mind of an artist, one that spans decades — reaching back before the days when Lee first picked up a film camera. For Lee, the gallery serves as a tribute to the moviemakers, athletes, musicians, writers and political icons who have changed the world and helped him form his vision.

Sitting down briefly, Lee gazed around the room. “You know what this is about? This is about love. These are people who touched me, inspired me. I’ve been lucky enough to be friends with some of them.”

The installation is filled with rare posters, film stills and lobby cards signed to Lee by a who’s who of elite directors, including Akira Kurosawa, Billy Wilder, Jean-Luc Godard, Lina Wertmüller, Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola. There’s an original Playbill from the 1943-44 Broadway production of “Othello” signed by its star, Paul Robeson, the first Black actor to play the role in a major production, and an original poster from the 1959 film version of “Porgy and Bess” signed by stars Sidney Poitier and Brock Peters.

The items from his extensive personal collection had been previously housed at his production company, 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks, in Brooklyn.

Said Lee, “This is really a very, very small part of all the stuff I have. I could fill the Brooklyn Museum. I’ve always been a collector. This is a real life’s work. People come to my office, and they say, ‘This is a museum.’ This is my pantheon.”

As he talked, audio clips from Lee’s films — the molasses-smooth jazz of “Mo’ Better Blues”; the vocal alarm clock of Samuel L. Jackson’s Mister Señor Love Daddy from “Do the Right Thing”; the cry of “Wake up!” from “School Daze” — played in the background.

Highlighting the gallery are autographs and personal notes from former President Barack Obama, Al Pacino, Harry Belafonte, James Brown and many others. Also featured are photographs of Lee with some of those who have moved him: One shows Lee with the late musician Prince and Chris Rock. Another shows him laughing it up with Scorsese, Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci.

Jacqueline Stewart, chief artistic and programming officer for the museum, said the Lee exhibit will be a key destination within the facility, situated between a large gallery featuring a timeline of Oscar winners and a gallery devoted to “The Wizard of Oz.”

“We want the museum as a whole to give people a sense of the labor and the imagination that go into filmmaking,” she said. “Part of that is demystifying the filmmaking process, and the start of that is thinking about where artists’ inspirations come from. Being able to occupy the mind space of an artist is what we’re able to do through Spike Lee’s collection.”

Calling Lee “an unapologetically Black filmmaker,” Stewart added, “It’s not just about the logistics of how he approaches cinematography, editing or writing. It’s about the core of what he surrounds himself with in his own workspace. We see that he surrounds himself with images and signatures, his personal contacts with a global range of filmmakers.”

As he started to move around the gallery, Lee outlined his early interest in connecting with his heroes: “It started as a kid growing up in Brooklyn with baseball cards and comic books. Me and my friends knew when the San Francisco Giants would come to New York. We knew where they stayed, and we’d wait for Willie Mays to sign our baseball cards. With the Atlanta Braves, it was Hank Aaron, and with the Pittsburgh Pirates, it was Roberto Clemente.

As a shrine to the Oscars and, more important, a tribute to the movies, the new museum is at its best when it sidesteps the obvious.

“In high school, I would swipe posters off ads in the subway. In my room growing up, I was surrounded by Walt Frazier, Willie Mays, Muhammad Ali.”

Although he was already in good spirits, Lee grew more excited as he pointed out items as if he was seeing the rarities for the first time.

He paused before a vintage poster of Marlon Brando: “This is the French poster from my favorite film, ‘On the Waterfront,’ and one of my favorite actors, Brando.”

Nearby were vintage posters for the Kurosawa classic “Rashomon.” “When I saw this in film school, it was the genesis for my first film, ‘She’s Gotta Have It.’ You have one event and people’s different interpretations of that event. These Japanese posters were signed to me by the late, great Kurosawa.”

Lee bent down before a poster for “Boyz N the Hood,” signed to Lee by the late director John Singleton: “My brother.” Above that was a poster for 1971’s “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song,” signed by its writer-director, Melvin Van Peebles, who died last week.

Lee said of Van Peebles, “The Godfather of modern Black cinema. The poster is signed ‘To Spike with love.’ This movie changed everything. Many people say blaxploitation followed this, but I don’t think that was Melvin’s intent.”

A section of one wall is occupied by original posters for “Star Wars,” “Apocalypse Now” and “Days of Heaven,” signed by their respective directors — George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola and Terrence Malick. “All these films mean something to me.” Close by were autographed posters for “Breathless,” “Bicycle Thieves” and the Brazilian film “Pixote.”

A poster for “Cool Hand Luke” drew a huge chuckle: “Here’s my man, Paul Newman! Signed ‘To Spike, who is Luke incarnate!’”

A circular podium in the center of the gallery contains the custom purple Gucci suit that Lee, who directed the 2009 documentary “Kobe Doin’ Work,” wore to the 2020 Oscars to pay tribute to Lakers great Kobe Bryant, who was killed in a helicopter crash the previous month. A podium also holds a custom gold guitar that was a gift from Prince, who had contributed several songs for Lee’s 1996 film “Girl 6.”

“I asked Prince for a guitar, and it showed up a year later,” said Lee. “He didn’t tell me it was coming — it just showed up. I said, ‘You gonna sign it for me?’ and he said, ‘Spike, you’re lucky you got the guitar!’”

He burst out laughing: “We had it like that, you know? We were good.”

As the Academy Museum’s chief artistic officer, Jacqueline Stewart will be in charge of screenings and events, giving the past relevance in the present.

Items will be rotated in and out of the exhibit, but Lee was already noticing things he would like to include. He’s been trying to track down Pam Grier to sign his “Friday Foster” poster. He really wants a harmonica from Stevie Wonder, who did the soundtrack for “Jungle Fever.”

Lee was also less than pleased that there were no items referencing “Bad 25,” his 2012 documentary about Michael Jackson and the 25th anniversary of Jackson’s 1987 “Bad” album.

He pointed to steps on the podium displaying trumpets from Terence Blanchard and Wynton Marsalis, as well as a tenor sax from Branford Marsalis. All those celebrated musicians have contributed to Lee’s films.

“MJ should be up there!” said Lee. “You gotta have Michael in here. I know they’re going to rotate stuff, but Michael Jackson can’t be coming off the bench. He’s gotta be in the game when the horn blows!”

While Lee is being celebrated by the Academy Museum and by New York’s Lincoln Center — which honored him in early September at its Chaplin Award Gala — the filmmaker is sharply focused on the future.

“I’m just beginning,” he declared. “I’ve got a lot of work to do, a lot of films, stuff I haven’t done before, other art forms. We had to shut down for COVID, but I’m ready to go.”

Ya’ dig? Sho-nuff.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.