When Ted Sarandos moved to Los Angeles 25 years ago, he was surprised that the film industry — an industry he would soon transform as a top executive at Netflix — had no real center. No single place where you could take in the sweep of its storied history. No showcase for its most precious artifacts.

“I was shocked that there was no Hollywood to see,” says Sarandos, Netflix’s co-chief executive and chief content officer. “You could do a random studio tour here and there but basically there was Universal Studios and Hollywood Boulevard — that was Hollywood.”

What the city sorely needed, Sarandos felt, was a museum dedicated to movies. He was hardly the first to feel that way.

A film museum had been a seemingly chimerical dream within the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences virtually since its founding in 1927. Bringing it to fruition proved a long and at times tortuous process — beset by cost overruns, construction delays, competing visions, infighting, a pandemic and a racial reckoning. Like a troubled movie production, it seemed to some in danger of ending as an expensive, heartbreaking flop.

The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures has opened as the ultimate celebration of Hollywood history, Oscar lore and today’s movie makers.

Now, with the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures set to open its doors Sept. 30, Sarandos believes, along with other key players in the effort, that the long-awaited cathedral of movies is landing at just the right time — perhaps when the film industry needs it most.

“When you think about how complex something like this is — with creative differences of opinion and just the logistical challenges of building in a major city — we should have expected a lot of delays,” said Sarandos, who is chairman of the museum’s board of directors. “But ... almost every delay led to something way better.”

For an academy that has weathered the #OscarsSoWhite controversy and continues to wrestle with declining viewership for the Oscars telecast, the museum’s opening is not just a triumph of logistics but also a chance for the group to continue its attempts to celebrate the art form of cinema while acknowledging some of the industry’s failures.

“Were there hurdles? Were there obstacles? Were there problems to solve? Yes,” said academy Chief Executive Dawn Hudson. “But for me — and I think for the board — there was never a loss of faith. I remember one of our board members, when he saw the first model, said, ‘This will be a beacon for our industry and a destination for all of Los Angeles and the world.’ And that’s true.”

Spencer the hawk’s job: Discourage other birds that might dirty the gleaming, glass building. Why hawks like him command top dollar.

For the academy, the stakes — financially and reputationally — are extraordinarily high. Tremendous time, energy and money have gone into thinking about, and then rethinking, how the brand ambassador of Hollywood should showcase movie history to the world. The next step will be seeing whether the general public, and the academy’s members, will embrace the museum’s warts-and-all portrait.

“Who says that those nearly 10,000 people — every one of whom has firm ideas of what is exactly correct — are going to be happy?” said one academy insider who has been deeply involved in the museum but spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the issue. “Making everybody happy is a fool’s errand.”

But Los Angeles finally has the thing so many people expect to see when they visit — a movie museum.

In October 2012, the academy announced a plan to build a museum in the former home of the May Co. department store on Wilshire Boulevard. The budget was $250 million. It would open in 2017. The announcement was met with equal parts excitement and doubt. A few years earlier, the academy had purchased land and commissioned French architect Christian de Portzamparc to design a $400-million complex that would feature large outdoor screens.

On Sept. 29, 2008, the day De Portzamparc presented his plans, the stock market plummeted nearly 800 points.

“Fundraising stopped. Planning stopped,” said Sid Ganis, who was the academy‘s president at the time. “The board got skittish. We all said, ‘We can’t do it now.’” (The Hollywood site was eventually sold and redeveloped into a mixed-use complex anchored by Netflix. “Fitting and proper, but what the heck,” Ganis said with a dry laugh.)

How the Academy Museum scoured film history to bring fans face to face with iconic items from “Black Panther,” “Alien,” “Batman Returns,” “T2,” “Dark Crystal” and more movie faves.

But in 2012, with renowned Italian architect Renzo Piano on board in collaboration with Californian architect Zoltan Pali, the academy felt certain it would meet the new project’s budget, having already raised an initial $100 million.

“That $100 million in pledges was the test,” Hudson said. “We came back to the board and said: ‘Here you go. Here’s our community. They’re already all in.’”

Piano’s plans were enormously ambitious, featuring a massive 130-foot spacecraft-like sphere — nicknamed “the Death Star” — suspended on concrete plinths that would house a 1,000-seat theater and connect to the retrofitted May Co. building via three bridges.

It would have been an enormous undertaking even if everything had gone smoothly — and everything did not go smoothly. Three years passed before ground was broken. Construction hit a number of snags. The budget swelled. Fundraising slowed. Doubts reemerged.

By 2017, as the original opening date came and went, there was growing concern within academy leadership that the project was a financial albatross. A March meeting of the board of governors turned tense and fractious, with some saying Hudson had let the project go off the rails. But having taken on $360 million in debt in 2015 to finance the project, the academy was in too deep to do anything but press forward. Boosted by a $50-million gift from Cheryl and Haim Saban, fundraising began to pick up even as the budget ballooned over $400 million.

“Filmmakers are used to the vicissitudes of the struggle of telling ambitious stories,” said current academy President David Rubin, who at the time was a member of the board of governors. “We’re used to the bumps in the road on the way to opening weekend. So regardless of others’ observations, we were undaunted.”

::

Even as construction proceeded, a still larger challenge loomed: figuring out what exactly this grand, costly film museum would be.

Under museum director Kerry Brougher, plans had been developed for a permanent core exhibition of film history titled “Where Dreams Are Made: A Journey Inside the Movies.” But many found the approach rooted in an outdated notion of Hollywood and its history.

In August 2019, just as construction was nearing completion, the academy announced Brougher was exiting the project; he said simply that it was “the right time for me to pass the baton.”

Ganis maintains that Brougher, who had served as curator at L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art, has a heart and soul in fine arts.

“He had lofty and somewhat historical academic ideas: How did the movie industry start? Where did it go?” said Ganis, who this year became the museum board’s first honorary lifetime trustee. “We all felt we wanted more. ”

To replace Brougher, the academy hired back Bill Kramer, who had served as the museum’s managing director of development and external relations from 2012 to 2016. With the clock ticking toward the 2020 opening, Kramer scrapped the permanent exhibition — amounting to 60% of the exhibition space — in favor of a more thematic and modular approach eventually dubbed “Stories of Cinema.”

“To move away from a linear narrative allows us to tell different types of stories and more balanced, diverse stories,” Kramer said.

The greater flexibility immediately raised the question of exactly whose stories would be told, an issue of ever greater urgency in the wake of #OscarsSoWhite and the #MeToo movement. How would the film industry’s own historical problems with racism and sexism be reflected in its splendid new museum?

The director couldn’t land work despite the 2002 success of “Real Women.” Now Patricia Cardoso gets long-overdue recognition at the Academy Museum.

A curatorial team of mostly women has surfaced the intriguing back stories and undertold contributions of women in filmmaking.

Under Kramer, 17 task forces were formed to represent each of the academy’s branches — from acting and directing to executives and public relations — in developing the new exhibitions. An Inclusion Advisory Committee was charged with helping spotlight the work of diverse filmmakers and expose historical omissions.

Tasked with leading that committee, producer Effie Brown had been dismayed by the museum’s initial handling of issues of inclusion.

“After seeing a presentation, I was like, ‘Oh, no, wait a second,’” Brown said. “Between Asian, Latinx, Black, Native American, women, LGBTQ — it was like, ‘What about our contributions?’ Things that were forgotten. Celebrating a person who was — I won’t go into it but, you know, problematic.

“I was able to raise my hand and say, ‘Hey, I think we may be in a bit of trouble.’ And the academy heard us, which was really beautiful, because sometimes when you speak up you aren’t met with such open arms,” she said. “It was really a massive rethink. And in the end, we actually got to an amazing place.”

As the Academy Museum’s chief artistic officer, Jacqueline Stewart will be in charge of screenings and events, giving the past relevance in the present.

It’s a delicate tonal balance to simultaneously celebrate Hollywood and acknowledge its sins. (Along with Dorothy’s ruby slippers, for example, the gallery for “The Wizard of Oz” includes darker references to Louis B. Mayer’s mistreatment of Judy Garland.) The process of calibrating that mix will continue after the museum opens, and Kramer believes such a juxtaposition is not only possible but necessary.

“We didn’t want those conversations about racism, sexism and oppression to be put in a separate room where people could choose to listen and engage or not to,” he said. “Telling honest stories and being transparent can be both celebratory and hard. You can do both.”

::

Just as everything was finally coming together, a pandemic hit. The December 2020 opening — announced by Tom Hanks on that year’s Oscars telecast in February — was pushed back to April 2021, then delayed again to September.

Wreaking havoc on nearly every aspect of the industry, the pandemic accelerated seismic shifts in the way movies are made and consumed. Now the museum must not only celebrate the medium’s past but also make a case that it has a viable future.

Oscar-nominated producer and academy member Michael Shamberg, a longtime academy critic, recently told The Times that he worries the Academy Museum won’t have the same draw that George Lucas’ Museum of Narrative Art will have when it opens in L.A. in 2023.

“If the admissions are down at the museum, they can’t just kick the can down the road,” Shamberg said. “They’re simply going to end up as an institution whose only mission is to preserve the past, with nothing to contribute to the future.”

For the academy, the financial health of the museum — which went nearly $100 million over its 2015 budget of $388 million — is of crucial importance. The effect of the pandemic on attendance clouds the picture. But looking at continued fundraising and the pace of sign-ups for membership, academy leaders are confident.

“Every week we have over 100 — sometimes close to 200 to 300 — new members signing up,” Kramer said. “We closed the $388-million campaign last fall, and we’ve been raising money for our first year of operations. People are stepping up.”

Of the delays that led to this moment, Hudson argues concerns have been overblown: “I have done home renovations that have taken a third of this time for 400 square feet. To realize this dream in [10 years] — it’s still miraculous to me.”

And as the opening looms, academy leaders unsurprisingly remain optimistic about both the museum and the art form it showcases.

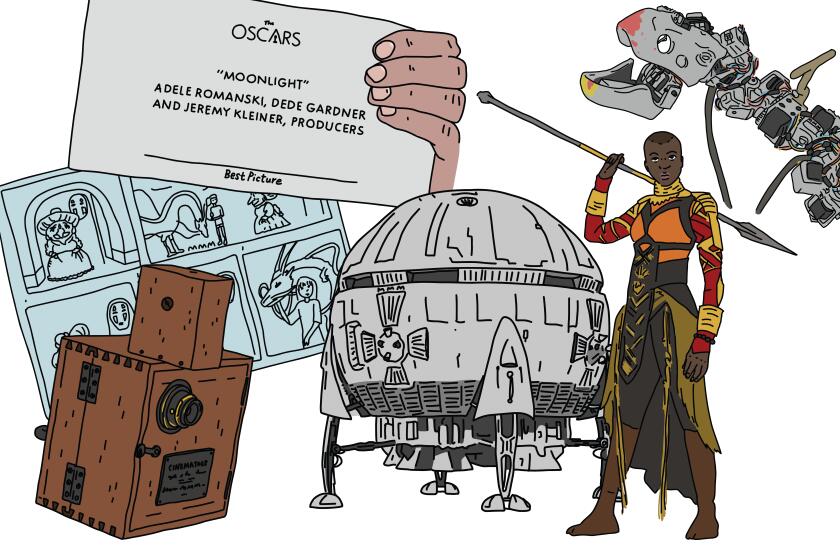

The Dude’s bathrobe from “The Big Lebowski.” The space shuttle from “2001.” The infamous Best Picture Oscars card for “Moonlight.” Insiders reveal their faves.

“This is a museum that really celebrates film, but it does it for the masses, in the language of the masses,” Sarandos said. “I think this is going to be a very commercially viable project for the city and for the academy.”

Ganis, who has been riding the roller coaster of the museum effort longer than almost anyone, wholeheartedly agrees.

“I say thank goodness we had those tough starts and stops and kvetches and moans over money,” Ganis said. “Because now we’re going to give the world this museum. When kids and adults come in … to see Hayao Miyazaki films on the big screen, the kids will say, ‘I want to be in that place. Take me to the movies.’”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.