Inside the Academy Museum room where you’ll meet R2-D2, E.T. and more icons of movie magic

In 1978, Nigerian artist Bolaji Badejo was discovered in a London bar and cast in the only film of his career, his thin 6-foot-10 frame making him well-suited to don the uniquely proportioned costume for a role a local production was desperately trying to fill: that of a menacing extraterrestrial with long limbs, razor-sharp teeth and acid for blood, stalking the crew of a spaceship.

The film was Ridley Scott’s “Alien” — and the nightmarish Xenomorph that Badejo helped bring to life would go on to spawn a sprawling sci-fi horror franchise, terrorizing Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley into the annals of cinema history.

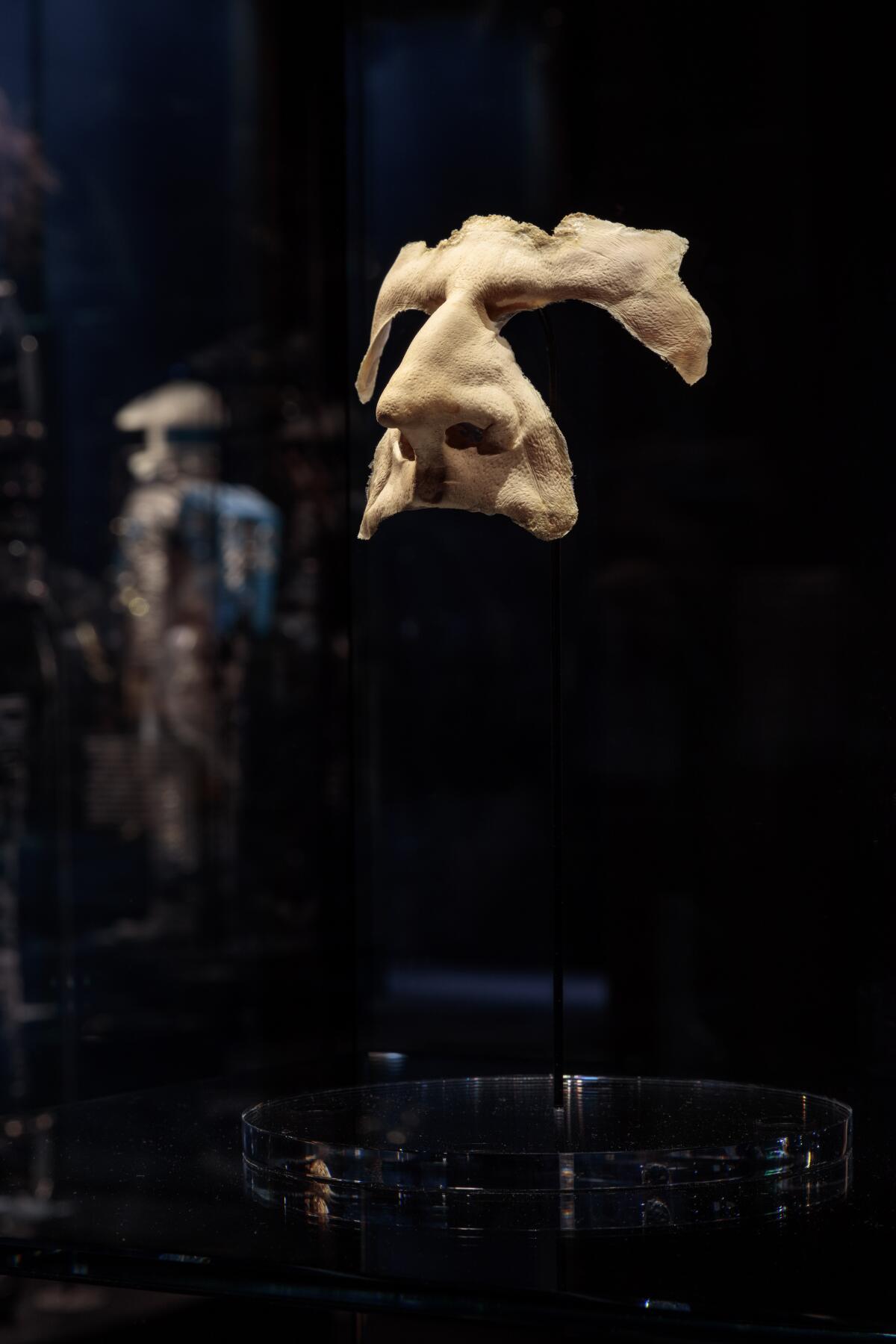

It’s one of dozens of iconic movie characters presented in the Academy Museum’s most fantastical, up-close and personal experience: The “Encounters” room, where the actual Xenomorph head worn by Badejo — designed by H.R. Giger and created by Carlo Rambaldi for 1979’s “Alien,” an Academy Award winner for special effects — greets you as you step through the entryway, its jaws open wide.

Nearby, fixtures from other fan-favorite universes invite visitors into their own nostalgic immersions: Okoye’s “Black Panther” outfit stands sentry with her spear-tipped staff, and both C-3PO and R2-D2 beckon “Star Wars” lovers for a closer look.

Even if these are not the droids you’re looking for, “Encounters,” part of the “Stories of Cinema” exhibition, is designed for different fandoms and (re)discoveries as guests wander from one vivid display to the next, taking in meticulously restored screen-used costumes, models and props from such films as “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “Blade Runner,” “Edward Scissorhands” and “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.”

Any number of feelings — awe, inspiration, romance, fear — can come flooding back in the span of a moment reconnecting with a movie that touched you.

The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures has opened as the ultimate celebration of Hollywood history, Oscar lore and today’s movie makers.

“It’s interesting how memory works, and that’s also the beauty of cinema because we remember dialogue and lines and things that are part of the pop culture landscape,” exhibitions curator Jenny He said in advance of the museum’s Sept. 30 opening. “But where did they come from? To make those neural connections because you’re in a space surrounded by these original objects is an experience you can only have when you’re in the space.”

Museum-goers taking in the three-part “Stories of Cinema” will first survey a kaleidoscope of transportive inventions from throughout film history, from early animation cels and stop-motion maquettes to the Dinosaur Input Device innovation that helped bring “Jurassic Park‘s” Tyrannosaurus rex to life.

It’s interesting how memory works, and that’s also the beauty of cinema because we remember dialogue and lines and things that are part of the pop culture landscape. But where did they come from?

— Exhibitions curator Jenny He

Then in “Encounters,” the moody final chamber of the multi-room “Inventing Worlds and Characters” section, the lights dim; here is where fans come face to face with creatures and characters that movies have lodged deep within their subconscious hearts and minds. That spark of remembrance, the specificity of place, time or emotion an image can evoke even years after seeing a film, is what curators hope will make the gallery a visceral experience for cinephiles.

“Visitors might come in to see one character or one object from a film but then be reminded by another of a memory that’s in the back of their head,” noted He.

Showcasing a small fraction of the academy’s collection of more than 8,000 items, the gallery includes several significant objects obtained at auction and on loan from private collectors, filmmakers and studios. The focus is on some of the biggest and most beloved Hollywood genre films of the last 50 years; each is presented in such a way that one may simply commune with an iconic object, or learn more about the craft, people and history behind the movie magic.

Bathed in shimmering light using an underwater effect designed to highlight its UV-painted details, the Amphibian Man from Guillermo Del Toro’s best picture Oscar winner “The Shape of Water” (2017), designed by Mike Hill and on loan from Legacy FX, commands attention from the center of the room.

“Del Toro wanted it to be believable that [Sally Hawkins] could fall in love with him,” He observed.

To the swoonworthy fish-man’s left, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s disembodied head — one of several animatronics used in the making of 1991’s “Terminator 2: Judgment Day” — shows the T-800’s endoskeleton peeking out from beneath fleshy cranial damage, as seen in the film’s finale.

“This was used for scenes where the metal was exposed. It would be cut together with Arnold and makeup, so the effects makers had to be very precise in matching his makeup,” said He.

In contrast, the Gelfling heroine Kira from 1982’s dark fantasy classic “The Dark Crystal” offers a different example of animatronic wizardry — part of an extensive assemblage on props and creature puppets in the academy’s collection gifted by the Jim Henson Co. and the Henson family.

With space limitations to think of, careful consideration went into the curation of the inaugural displays, which will be updated post-opening as different items cycle in and out. Many items highlight the academy’s own collection of memorabilia obtained through private auction, gifts, donations and rescue.

When effects company Matte World Digital closed its doors in 2012, for example, the academy obtained several pieces that were used to bring 1992’s “Batman Returns” to life. Matte paintings of the Bat Cave and Gotham Park and a miniature model of Cobblepot Manor, home of the young Oswald Cobblepot, are featured together in “Encounters,” drawing focus to the film’s atmospheric world-building and design.

But displaying the miniature seen at the start of the Tim Burton film was made possible only with the help of John Goodson, one of the original fabricators, who worked with the academy’s conservation team to restore the piece to its original condition decades after it was created. It turns out that calling up filmmakers for help verifying, restoring and locating certain items otherwise lost to time is much easier with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Rolodex at your disposal.

That’s how He’s team was able to procure a piece of Wakandan history for the gallery. Seeking a specific item from “Black Panther,” curators tapped the help of Oscar-winning costume designer Ruth E. Carter to track down actor Danai Gurira’s Okoye costume. The display, on loan from Marvel, allows visitors to zero in on the specifics of the design, such as how her rank as general is reflected by her gold collar.

“Even though it’s a uniform that every one of the Dora Milaje wears, her costume is very distinctive and that detail really comes forth when you’re able to see it in person,” said He. “It’s emblematic of Ruth Carter’s use of Afrofuturism in the costume designs of ‘Black Panther.’ Here, not only are we looking at ‘Black Panther’ as the work of art, but we’re looking at her costume as a work of art.”

Film objects can transport you to the moment you saw a movie for the first time, but they also give you a direct and tangible connection to the precise moment an image was caught on camera, says collections curator Nathalie Morris, who is always on the lookout for historically meaningful acquisitions that speak to the organization’s mission of advancing the “understanding, celebration and preservation of cinema.”

But most of these items were never designed to last years, decades or centuries. “They’re made for the purpose of getting a movie made and capturing an image on-screen, so you’re often fighting against the inherent nature of that object,” said Morris. “Everything wants to degrade that. That’s the nature of life.”

So before many of the pieces in the academy’s collection make their way to public view, they first spend time in the Debbie Reynolds Conservation Studio, downstairs at the Academy Museum.

It’s there, ahead of the gallery’s long-awaited opening, that one of three rare full-body animatronic E.T.s from Steven Spielberg’s collection is being prepared for its “Encounters” debut — coincidentally also designed by “Alien” artist Rambaldi, who won visual effects Oscars for his two very different out-of-this-world creations.

Conservators also did extensive work to restore a 6-foot-tall Gourmand Skeksis from “The Dark Crystal,” seen on display draped in elaborately layered robes with delicate tactile body detail, by resculpting and reattaching various elements that had deteriorated over time.

It’s not uncommon for academy conservators to rewatch a film hundreds of times to match original details of a piece. Armed with a laser pen and a cinephile’s deep knowledge of facts, dates and behind-the-scenes lore, He pointed out two of the gallery’s most extraordinary pieces.

A silver spacesuit worn in Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey,” one of the most influential films of all time, is one of the first items visitors might see upon entry. But objects, like the movies themselves, have secret lives of their own. Purchased by the academy at auction, He says, the previous owner was said to have worn the suit walking around Manhattan’s West Village.

“This is another film that we’ve watched thousands of times, frame by frame, to see how the spacesuit looked during filming, and then we, of course, had to restore some elements,” said He.

When the academy purchased the Aries 1B trans-lunar space shuttle visual effects model, another rare “2001” item, at auction in 2015, it began a five-year restoration and conservation project.

“When I looked at the object in person for the first time, I remember thinking, ‘Oh, wow — this is the way the ship flew.’ All of these things just came back to me just from looking at that object,” said He.

But to restore the 32-inch-high Aries 1B to its original 1968 screen appearance, conservators had to source parts and replace missing components. The final installation includes lighting elements that illuminate the model from within, as if the spacecraft has just touched down on the moon with Dr. Heywood Floyd inside.

“Our conservation team went to the original model kits to restore these elements. It’s such a great journey,” He marveled with a smile. “And the story, of course, is a story in and of itself.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.