I’m a South Korean adoptee in America. And I feel more invisible than ever

After “Parasite” won the Academy Award for best picture in February, South Korea dominated headlines. Two months later, this small cultural and economic powerhouse finds itself basking again in the American media spotlight — this time for its swift and effective response to the coronavirus outbreak.

While reports in the U.S. have focused little on such places as Hong Kong and Taiwan, with their nine confirmed COVID-19-related deaths combined, South Korea has continued to receive outsize praise for its handling of the crisis, despite its Big Brother tactics, which have also been a factor in Singapore’s approach to COVID-19.

The novel coronavirus struck terror in this conservative country in part because its wide-scale technological capabilities threaten those who visit LGBTQ clubs, mistresses, psychiatrists, cosmetic surgeons — all culturally shamed activities, though little of this is given much airtime here.

So why do most Americans view South Korea as a bastion of liberal democratic values?

I was adopted from South Korea in 1981 at 14 months old and raised by a white evangelical family who would tell me a movie like “Parasite” comes from the devil. Growing up, I never knew the reason I was adopted at all was that, in the 1950s, America was the parasite.

The Korean War, the third most devastating war of the 20th century behind World Wars I and II, produced 100,000 mixed race children, all unwitting catalysts in the birth of international adoption: half-white abandoned children of American GIs and prostitutes from the camptowns that were officially condemned but quietly expanded by the U.S. military.

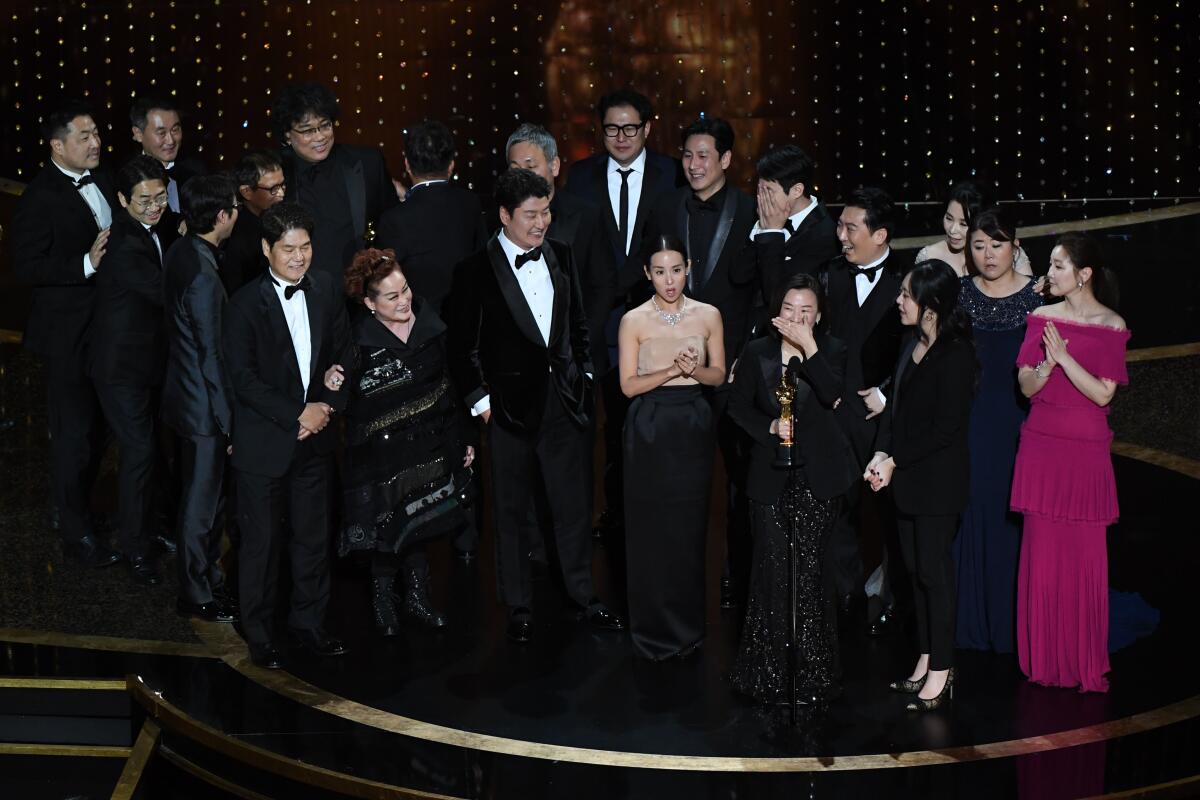

Seventy years, three generations and 250,000 Korean “orphans” later, South Korea broke the pagoda ceiling with Bong Joon Ho’s “Parasite,” which became the first foreign-language film to win best picture since the academy’s inaugural Oscars ceremony in 1929. The film, which is now streaming on Hulu, also earned more than $250 million at the global box office. Should I celebrate?

For novelist Steph Cha, K-pop band H.O.T. and action film “Shiri” are a few culture predecessors to this hallyu moment of global success for “Parasite” and BTS.

It was disorienting and disembodying to watch American culture, my culture, finally acknowledge a film — though not its actors — that came from a face like mine. It was even more dizzying to watch an Academy Award go to South Korea, the country that erases my existence as an adoptee even harder than the American media ignores Asians, unless we’re playing surgeons, convenience store owners, martial arts masters or Chinatown extras.

“Parasite’s” main competitor for best picture was “1917,” an epic all-white throwback to one of the only two wars most white people care to remember. From an adoptee perspective, which is better? The movie about white people fighting a white war over 100 white years ago? Or a film revered by a country that erases its Asians made by a country that erases its adoptees?

The booming postwar trade of international adoption in South Korea created and fed a market that served the combined interests of an occupying nation wanting to ignore the lives that its servicemen had fathered and a country economically devastated by the active fighting from 1950-1953. To say South Korea was poor after the fighting ended is an understatement of propagandic proportions. Some estimates cite that 10% to 20% of the population was massacred (this is without North Korea’s numbers), approaching the number of Jews killed in Nazi Germany.

More bombs were dropped in Korea than in Germany and Japan combined during WWII; nearly twice as much napalm was sprayed there as in Vietnam. It is the war where we coined the term, “weapons of mass destruction.” And this is without the nuclear bomb President Truman considered dropping the minute the war started. Hiroshima, Nagasaki and Seoul.

Korean religious sect with high coronavirus rate values secrecy

The main U.S. military base in the middle of Seoul was the only economy in the country for decades, and it shows. Landing at Incheon airport for the first time, I knew immediately that I wasn’t in China or Japan, not with all the neon crosses puncturing the skyline. No wonder a pivotal coronavirus outbreak happened in one of South Korea’s many Christian shadow-cults before it metastasized throughout the country.

In 2006, 13 years before his “Parasite” triumph, Bong Joon Ho made another film called — wait for it — “The Host.” But instead of embarking on a class-conscious domestic critique, “The Host” calls out the American military and its collusion with the South Korean government. It centers on an amphibious monster that suddenly emerges out of the Han River, attacking an unsuspecting crowd, striking terror throughout Seoul. After a mass funeral for the victims, the government rounds up survivors to place in quarantine: The creature is also the host of a deadly, unknown virus.

Except there is no virus: The “virus” serves as an excuse for the American military to release “Agent Yellow” into the atmosphere — a direct reference to Agent Orange, the toxic herbicide that the U.S. sprayed in Korea in the late 1960s (but didn’t admit using there until 2000). As our protagonists in “The Host” escape a conspiracy of hospitals, the police and South Korea’s Orwellian surveillance system, the U.S. military presence plays the unmistakable antagonist.

Unlike “Parasite,” which features no white actors, “The Host” opens with one — its first scene takes place between an American military scientist (Scott Wilson) and his Korean assistant (Brian Lee), both wearing full scrubs in a dingy lab lit with all of the charm of a basement bunker. Wilson commands Lee to dump 200 bottles of “dirty formaldehyde” down the drain into the Han River despite Lee’s protests; the scene recalls a real-life ecological disaster that occurred in 2000, when the U.S. military dumped 20 gallons of formaldehyde into the Han, the source of drinking water for Seoul’s 12 million residents. The first monster we meet in “The Host” isn’t a CGI creature, it’s the U.S. military, the monster that creates “the monster.”

South Korea still hosts nearly 30,000 American soldiers, and prostitution camps still exist to service these men, fueling its red-light districts. Americans call it the Forgotten War, but the Korean War is anything but forgotten in South Korea, which has made it the core of the country’s national identity, despite the fact that this war was never really between the two Koreas, but rather North Korea and the U.S. or, perhaps more accurately, the U.S. and China.

The new golf course and clubhouse will open next month.

Paranoia about this war is the explanation “Parasite” gives for the basement shelter in the chic residence at the heart of the film: “A lot of these rich people, they build bunkers and secret rooms in their homes,” the former housekeeper explains as she scans the secret, subterranean apartment. “You know, in case the North Koreans invade ….”

South Korea rose from the ashes of its bombed-out past to rank as the world’s 12th largest economy by following Germany’s post-World War II lead, from the “Miracle on the Rhine” to the “Miracle on the Han.” But it wasn’t entirely a miracle. South Korea benefited greatly from not only the profits (tens of billions of dollars) gained through the selling of its infant underclass via international adoption but also the untold costs saved by never having to create any social welfare program to speak of. Korea currently ranks 34th among the 36 OECD countries in spending on social programs as a percentage of GDP, sitting between Turkey and Chile.

With an economy thriving in the 21st century and technology from the 22nd century, South Korea’s social values are still smack in the middle of the 19th century. As recently as 2016, Bong was blacklisted along with 9,000 other artists. Abortion was decriminalized only last year, gay men are still being thrown in jail, there is still no way to force fathers to pay child support, sex ed guidelines suggest that victims are to blame for date rape and being drunk is a legal defense for rape.

If Asians like me feel erased in the U.S., it is minor in comparison to the alienation of adoptees returning to Korea, where the natives are mostly unaware we exist and meeting us is usually the first time they’re hearing about it. And why would they know? We are here, a quarter-million of us, scattered across white Christian nations. We do not exist in their textbooks or their museums. Though Holt International — the Amazon of adoption agencies founded in 1956 by a right-wing evangelical — has a predominant presence in Seoul, few Seoulites think to ask why. Likewise, even the most cosmopolitan Westerners often fail to ask themselves why so many Koreans in America are adopted (one out of every 10).

It’s been a long week for all of us, so forgive me if I don’t have the energy to participate in a debate about whether President Trump calling the virus “Chinese” is racist.

So how is an adopted Korean cinephile to feel when, knowing all of this, she sees South Korea score four major Oscars? When the country that sold her wins big in the country that bought her? When the country that doesn’t know she exists creates a groundbreaking work of art, a blend of Hitchcock and Kurosawa K-mashed into a cinematic genre-f—, and it receives film’s highest honor in the country that so rarely casts people who look like her?

In a way, it doesn’t feel like anything. It’s like if China won. Who cares? What even is South Korea anyway? BTS? A hanbok? An old Korean woman telling me I should get married while I stand there looking like a stereotypical lesbian in a country that erases gay people too? It feels like when I was a kid and something Korean happened, like the Olympics, and people looked at me as though I was supposed to feel some kinda way. And I really just don’t. Angry? Meh. Sad? I guess. It is, after all, another reminder that, in an existential sense, there is no country for adopted Koreans.

After a moment of stillness, however, I do get the feels — exactly as I did three years ago when I learned that, decades earlier, Bryant Gumbel had spilled the Korean tea about adoption during the country’s greatest moment of pride: the 1988 Seoul Olympics. “Though the Koreans enjoy showing off their country to the world during these Games,” he stated over international airwaves, “there are some aspects of their society they’d prefer we not examine so closely, and one of those concerns the exportation of Korean orphans for adoption abroad.”

A reporter had envisioned simply saying ‘thank you’ to his biological mother. But seeing her pain over giving him up and her shame at being a single mother, it was not so simple.

In his two-minute report, he described adoption as “embarrassing, perhaps even a national shame.” The media, including the New York Times, published stories criticizing the commodification of children and, for the first time, international adoption was placed under a critical lens: The narrative shifted from agencies, governments and Western parents to adoptees, no longer the secret in Korea’s basement.

There are now stories told by Korean adoptees over three continents in many languages, describing myriad lives that all begin the same way: We lose our mothers, our country, everything but our faces. And our voices, which communicate in different mediums: News & Documentary Emmy-nominated filmmaker Deann Borshay Liem, Belgian animator Jung Henin, Swedish graphic artist Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom and a growing community of Korean adoptee memoirists such as Jane Jeong Trenka, Nicole Chung, Jenny Heijun Wills and, soon, myself.

So watching “Parasite” win the Oscar, I feel empowered and proud, but not for the reasons anyone might think.

The truth is, when the light shines on South Korea, particularly from the constellation of American movie stars, it’s a moment for us adoptees to share the limelight, to be seen by the two powers and cultures that erase different parts of us. It’s a moment to show ourselves, our shared history. There is no South Korea without us, and yet we will never truly be Korean.

A South Korean man flown to the U.S. 37 years ago and adopted by an American couple at age 3 has been ordered deported back to a country that is completely alien to him.

But we can be American, or so we are told. We can be anything but the Korean face that never lets us forget that we came from a place that forgot us. In this, there is a lackluster redemption, like winning the popular vote but losing the election.

It makes sense that Bong would end “Parasite” with a broken fantasy, an impossible dream from a broken boy’s broken brain. Adoptees, too, have a fantasy: That America will someday hold the South Korean government and private adoption agencies accountable for hiding information, changing our names so that our birth families can’t find us and shifting our birth dates to make us younger and more marketable; that the Korean government will stop with its empty gestures, like setting up an “adoptee outreach” department with no English speakers or offering DNA tests to adoptees overseas while banning Korean birth mothers from being tested.

In a way, Bong feels more international than national, more like me than an actual Korean. A subversive outsider, a spiritual exile.

Perhaps as we, like him, speak our truth to the world, we can find a place in it. Maybe someday the world’s hosts will realize they are just parasites by another name, and my native and adoptive countries will reckon with their past. And maybe, when the virus clears — leaving so many truths exposed — the real healing can begin.

Mee-ok is a Boston-based essayist and poet who was raised in Morgan Hill, Calif.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.