Singapore says its coronavirus app helps the public. Critics say it’s government surveillance

SINGAPORE — One of the most effective ways authorities can limit the spread of a pandemic is to immediately locate, test and isolate anyone who’s had contact with a carrier of the disease.

But pinpointing those contacts is painstaking. An infected person can’t reliably remember the dozens or more people they’ve crossed paths with in the preceding days or weeks.

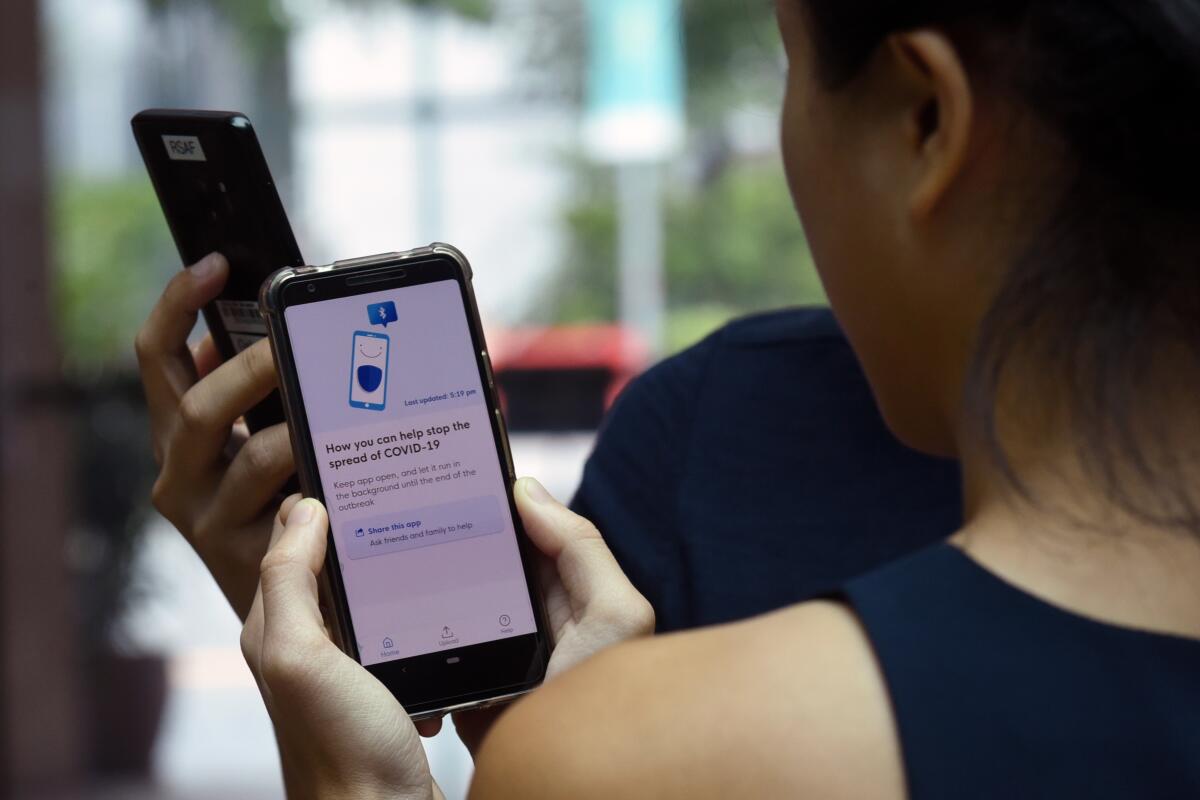

With that in mind, the Singaporean government introduced an app that will alert users if they’ve been in close proximity with a confirmed case of the coronavirus, helping authorities slow the spread of a disease that’s surged in the city state over the last week.

The app, called TraceTogether, works by exchanging short distance Bluetooth signals with other users of the app, giving officials a database to track potential COVID-19 carriers.

The app is being offered voluntarily but it comes at a time when governments across the globe are increasingly seizing on location data to combat the pandemic. The targeting of an individual’s movements is stoking tensions and raising civil rights questions over public health and personal privacy.

Countries including China, South Korea and Israel are tracking users’ cellphones to varying degrees to warn their citizens about potential infections and to chart the spread of the disease — a technological tool that didn’t exist during past outbreaks.

Such advances are leading to wider surveillance and a deeper reach by governments into the lives of their citizens. They require a growing acceptance of diminished privacy — a sacrifice many are willing to make against a global health crisis — in an age when more than a few governments and companies have squandered public trust in their ability to safeguard personal information, experts say.

“The attitude around digital technology has certainly changed since the 2014 West Africa Ebola epidemic. Back then, it was very difficult to deploy digital technology for surveillance due to doubt in its utility,” said Anne Liu, a health technology expert at Columbia University. “Six years later we’re seeing more confidence in the tech, but less so in the people who deploy it and their intentions with the data.”

South Korea’s aggressive testing and radical transparency have contributed to a dramatic decline in the rate of coronavirus infections.

But it’s come at a price for some of the 9,000 people who have contracted COVID-19. South Koreans are provided such immense detail about new cases and their recent whereabouts that it’s given citizens fodder to speculate on alleged romantic affairs and the means to dox suspected cases.

The deluge of information prompted the National Human Rights Commission of Korea to warn that people sickened by the virus now face a second trauma of harassment and ridicule, leading some South Koreans to fear social stigma more than the disease itself.

In Israel, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has been accused of using the pandemic as a pretext to enhance his powers after the government issued emergency measures allowing internal state security to track citizens’ cellphone data to curb the disease.

The move drew an immediate rebuke from critics and civil rights groups who feared it would set a precedent for the embattled prime minister to exploit.

This month, millions of Iranians were reportedly pinged by the government on their smartphones, urging citizens to download an app that claimed it could determine if users and their loved ones were infected by the coronavirus. Millions signed up despite the software’s dubious claims, ostensibly giving the autocratic regime access to personal location data for swaths of the country.

Taiwan, lauded for its early success combating the coronavirus, recently introduced a digital fence using cellphone data to enforce quarantines of people required to stay at home. Those under watch must leave their devices switched on and are called unannounced by authorities to ensure they haven’t left their homes.

No country, though, has matched the technological lengths to which China has gone to restrain the virus. Partnering with internet giants Alibaba and Tencent, the government is assigning citizens color codes that denote their health status, which in turn grants them access past checkpoints or even entrance to a restaurant or a subway station. Users have reported being color-coded erroneously and being unable to contact the app providers to change their status.

The software strengthens the ability of Chinese authorities to track people in a country that already uses widespread facial recognition to suppress opposition. Human rights advocates say the technology will probably remain in place after the pandemic is over.

“In many cases, the fear and panic have allowed governments to impose quite drastic measures which can be very difficult to roll back,” said Maya Wang, a senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Once you have a system implemented, they become normalized.

“Governments have a responsibility to ensure public safety and health; however, in emergencies like this they still have to respect human rights, which includes rights to privacy,” Wang added. “Any interference in privacy has to meet standards of legality, proportionality and necessity.”

Expectations of privacy and a patchwork of laws — along with revelations that after Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the government increased phone surveillance — make it difficult for contact tracing based on cellphone information to take hold in the United States.

The Trump administration, however, is in talks with Facebook and Google to use aggregated, anonymized location data to track the disease, the Washington Post reported last week. There’s growing sentiment in the U.S. that technology can play a vital role in stemming the pandemic.

A group of technologists, epidemiologists and medical professionals recently signed an open letter outlining ways Silicon Valley, whose companies, including Facebook, have been blamed for an eroding personal privacy, can assist. Among them was a call for Apple, Google and other mobile operating system vendors to provide their users an opt-in contact tracing feature that would also protect people’s identities.

“If such a feature could be built before SARS-CoV-2 is ubiquitous, it could prevent many people from being exposed. In the longer term, such infrastructure could allow future disease epidemics to be more reliably contained,” read the letter, whose signatories included Peter Eckersley, a distinguished technology fellow at the digital-rights-focused Electronic Frontier Foundation.

A computer scientist at MIT led a team that developed a prototype app called Private Kit: Safe Paths that shares encrypted location data for contact tracing between phones rather than sending it to a central database. The aim is to ensure a user will know they’ve come in close contact with someone carrying the coronavirus while preserving the carrier’s anonymity.

One of the keys to any such app will be reaching critical mass to reverse the growth of the outbreak.

New COVID-19 cases have surged in Singapore over the last week as returnees from overseas raise the risk of more community transmissions. To promote Singapore’s TraceTogether, which was launched Friday, schools and private companies have advocated the app’s use, calling it a social responsibility, like hand washing.

Unlike many parts of the U.S., the island nation of 5.7 million has resisted lockdowns. But in a sign of the deteriorating situation, the government announced Tuesday that starting Thursday night, bars, nightclubs and movie theaters would close and gatherings of more than 10 people would be prohibited for at least the next month.

Until recently, Singapore appeared to be a rare bright spot in the battle against the coronavirus. The rise in confirmed cases will probably now aid the government’s bid to have TraceTogether widely adopted.

Privacy matters don’t elicit concern in the de facto one-party state like they do in the U.S. or Europe. Government surveys show more than three-quarters of Singaporeans trust the way authorities handle personal data.

That sentiment has allowed Singapore to embark on its Smart Nation initiative, which aims to digitize vast corners of everyday life with cashless payments and facial recognition cameras on lampposts, with little resistance.

Still, the country isn’t immune to data breaches. In 2018, its largest health network was hacked, resulting in the theft of 1.5 million patients’ records. Last year, a former American expatriate leaked the names of more than 14,000 HIV-positive individuals in Singapore after gaining access to the data through his partner, a Singaporean doctor.

Developers of TraceTogether say that users’ identities will be anonymized and that the app doesn’t track location, but proximity between users by using Bluetooth, not GPS or cell signals. The information collected is stored on phones and erased after 21 days. The only information stored on government servers is provided by users confirmed to have COVID-19 who agree to share their logs.

The app can identify users within a 6½-foot radius with a duration of contact of at least 30 minutes. Information gleaned from the app will only be used for contact tracing, the government says.

The government says it will make the app’s underlying technology available to other countries.

Times staff writers Victoria Kim in Seoul and Alice Su in Beijing contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.