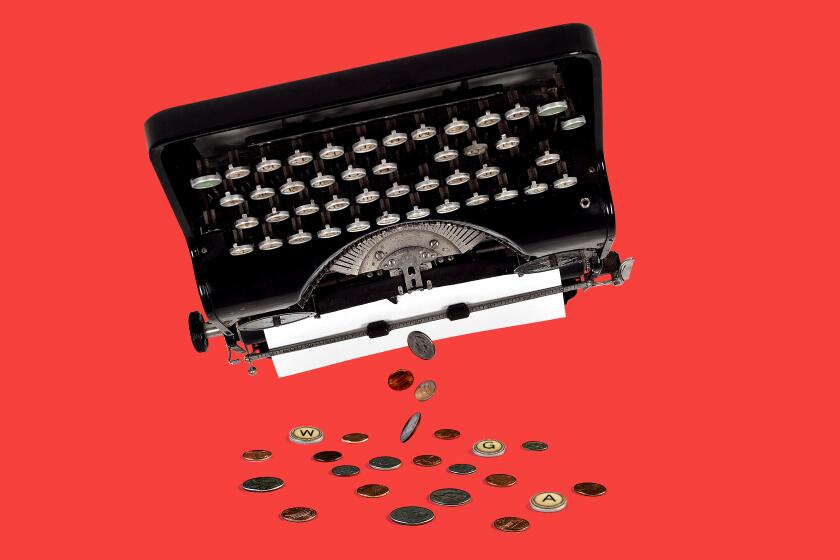

They’re on strike, but these writers are finding ways to write and create

In 1955, James Thurber, whose peerless wit made him one of the most important American writers of the 20th century, recounted the following exchange:

“I never quite know when I’m not writing. Sometimes my wife comes up to me at a party and says, ‘Dammit, Thurber, stop writing.’ She usually catches me in the middle of a paragraph.”

Thurber, whose prolific career included “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” and “The Battle of the Sexes” (both adapted into films), captured the occupational hazards inherent in the writer’s mind. Writing is not some industrialized, mechanized process; there is no time card.

The writers’ strike, now in its third month, has done for the thousands of members of the Writers Guild of America what Mrs. Thurber had demanded of her husband — forced them to stop writing.

Under WGA strike rules, union members are prohibited from providing writing services for any and all companies that are part of the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers and a host of related ancillary activities.

In other words: no writing, no pitching about writing and no talking or schmoozing about said writing.

While it’s one thing to stop writing, it’s another to turn off the creative spigot entirely. Writing is a profession in which a constant stream of thoughts courses through one’s mind, tumbling into ideas and words onto pages that become TV shows, feature films, books and plays. Stop writing? Might as well ask a hen not to lay eggs or the sun not to shine.

The 2023 writers’ strike is over after the Writers Guild of America and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers reached a deal.

Or as Rachel Shukert, a writer on “Glow” and “Supergirl,” expressed in a tweet less than two weeks into the strike: “I pitched my entire vision of seasons 2,3,&4 of AND JUST LIKE THAT to our nanny this morning. She needs me to get back to work.”

Although cut off from the economics of putting pen to paper or finger to keyboard, scores of WGA members are using their downtime and when not picketing the studios to channel their creative élan. Hollywood scribes have sought to scratch their creative itch without running afoul of guild rules, doing such things as writing books, mentoring war-torn playwrights, making pottery and tending chickens.

Last year, after Russia invaded Ukraine, screenwriter and playwright Jacquelyn Reingold began working as a writing mentor with Young Playwrights Ukraine. Reingold is one of 16 screenwriters and playwrights mentoring teenage Ukrainians, most of whom have been displaced by the war. The strike, she says, has given her more time to devote to the project.

They meet thrice weekly over Zoom, as the Ukrainians write 10-minute plays distilling their experiences with the war.

Workers in film and TV, most of whom are pro-union, have been trying to make ends meet amid a dual strike of Hollywood actors and writers.

The program was created by playwright and screenwriter Laura Cahill. In July 2022, the works were performed over Zoom by professional actors and subsequently produced at the Orion Theater in Stockholm. Another performance is being planned for August, and a collection of the plays is scheduled to be published as well.

During the strike, the New York-based Reingold, who has worked on the Paramount+ series “The Good Fight” and the NBC series “Smash,” began writing a play of her own, but she said she has found a wellspring of inspiration and dedication in the young Ukrainians.

“My other creative muscle is working with other writers,” she said. “I’m not allowed to be in a writers room. And this is kind of like a writers room, except we are a group of adults and then a group of teenagers who are living through a traumatic experience that they’ll never forget in their lives. So we are both sharing ideas about writing and teaching.”

It is precisely the kind of activity that “happens naturally in a writers room,” she said. “I hope these teenagers find meaning in what they’re going through, through their writing.”

For Kale Futterman, writing is a basic element of life, much like oxygen.

“I struggle to process the world without making stories out of it,” she said. “Even when I am telling myself I don’t need to go write a new sample or a new pilot, there is just something about my writer brain that everything I encounter ends up becoming, ‘Oh, can I make a story out of this?’”

I struggle to process the world without making stories out of it.

— Kale Futterman, writer

When the strike began, the Santa Monica-based Futterman, whose work includes the Netflix series “Ginny & Georgia” and the Lifetime feature “Black Girl Missing,” had just finished the script for a pilot and was just hours from sending it. But rather than dive into another script, she decided to try her hand at another creative passion, a fantasy novel.

“I’ve been sort of afraid to try for a while,” she said. “I’m a huge reader. I especially love reading a lot of fantasy. I’ve done a lot of grounded contemporary stuff for my professional career, but I have all of this time, so I figured, let me try something that feels completely out of left field for me.”

Beyond her novel being “set in a world different from our own,” Futterman said the project is allowing her to stretch in other ways.

“In screenwriting, it’s so much about what can you actually see is onscreen. For me, a pivot has been thinking about the internality of character.

“I’m really allowing it to just be a creative exercise that I’m enjoying.”

The current fight between writers and their studio bosses is nothing new. The quest for respect goes back to the earliest days of Hollywood.

When the strike turned to dust a project Donal Lardner Ward was pitching, he decided to dust off what he called the 40-year “elephant in the room.”

Ward, who co-wrote and co-directed the 1993 independent film “My Life’s in Turnaround” and more recently was a writer on the Showtime series “The Affair,” had a childhood filled with larger-than-life characters and colorful real-life tableaux. He is the great-grandson of writer and humorist Ring Lardner — a contemporary of Ernest Hemingway — and the grand-nephew of Ring Lardner Jr., the Academy Award-winning screenwriter (“M*A*S*H,” “Woman of the Year”) and blacklisted member of the “Hollywood Ten.”

His father, Donald Ward, was one of the founders of Elaine’s, the fabled Manhattan restaurant that from 1963 until it closed in 2011 was the place the New York Times called “a see-and-be-seen hangout for writers, editors and actors.”

Ward, who lives in New York, realized that he had a significant story to tell: his own. “I’ve just never been able to wrap my head around it and have avoided it.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, he began digging, but it wasn’t until the strike that Ward got serious.

After he sat down to work, he said, “I just looked up and I had 20,000 words that had just poured out of me. I couldn’t stop. Every day I was more excited to get back in front of the keyboard. It was like a drug.”

Not only has Ward found the process cathartic on a personal level but he has also reveled in the chance to simply write — without the usual limitations of writing for movies and television.

“There was something just so freeing about writing prose,” he said, “just barreling ahead, just getting it out.”

And there was an added bonus: The process is free of the dreaded studio notes. “Nobody’s going to be trying to say, ‘Hey, you know, can you set this on Mars in a spaceship instead?’”

The last writers’ strike, which lasted 100 days in 2007-08, turned into a fertile and influential period for some writers, birthing what would become the DNA for successful internet content.

Funny or Die, the experimental comedy video website and film-television production company, got its start when director and former “Saturday Night Live” writer Adam McKay, Will Ferrell and writer-director Chris Henchy said, “Let’s screw around.”

That lark produced a two-minute sketch, “The Landlord,” featuring Ferrell arguing with his potty-mouthed landlord, played by McKay’s then 2-year-old daughter Pearl. An instant viral hit, Funny or Die soon became a launchpad for cheap, garage-style sketches that frequently featured the work of famous contributors such as Judd Apatow and Paul Rudd.

It also became something of a spinoff generator. The site’s associated production company went on to make genre-busting programming, including the lacerating online talk show “Between Two Ferns With Zach Galifianakis.”

During this go-round, one of the first creative seedlings of the strike occurred when the late-night shows shut down.

Greg Iwinski, a former writer for “The Late Show With Stephen Colbert” and “Last Week Tonight With John Oliver,” and other late-night cohorts began producing a semi-regular YouTube show called “Contract TK” (initially known as “Picket Tonight” and at times, “The Jokes You Love From the Picket Signs but We’re Saying Them Out Loud”).

The show sends up the studios while raising trenchant, humor-laced points about why the writers are on strike in the first place.

In one bit, Iwinski deadpans, “As you may know, writers are on strike. What you might not know is according to nine out of 10 doctors, if a late night writer does not do monologue jokes for too many consecutive days, they die.” This was followed by a photo montage of those nine doctors, including Dr. Fauci, Dr Pepper, Dr. Phil and Dr. Zhivago.

Last month, “Late Night” host Seth Meyers and his brother Josh Meyers, an actor and writer on “MadTV” who also appeared on “That ‘70s Show,” launched the podcast “Family Trips With the Meyers Brothers,” where the brothers recall their own sometimes less-than-idyllic vacations along with guests including Amy Poehler.

Daniel Dooreck’s fascination with motorcycles, flash tattoos and cowboys comes alive in the hand-thrown vessels he creates in his tiny Echo Park garage.

For some writers, the strike is an opportunity to detour entirely from storytelling day jobs.

Janet Lin, a writer and producer in Los Angeles on such shows as “Bridgerton” and “The Orville,” found that hours on the picket lines left her too exhausted to pick up a pen. So when other writer friends suggested she join them at a pottery studio in Culver City, she jumped.

A self-described massive fan of the British show “The Great Pottery Throw Down,” Lin began taking a weekly wheel-throwing class. “It’s a different kind of creativity, which is nice,” she said. “It’s a tactile creativity.”

Before the strike, Lin was working on three development projects for studios including Disney+, Netflix and the cable network AMC and was frustrated that two of the projects had “died.”

Pottery has shifted her perspective.

“It feels ephemeral when I’m writing these scripts that will never see the light of day,” she said. “It’s not like your writing will be in print and it won’t be remembered forever. It’s like we’re creating air. We’re not building a bridge, we’re creating entertainment.”

But when she’s at the wheel, Lin said, “You make something, and then at the end of the day, it gets fired and you glaze it and you bring it home and you can use it. It’s a thing that will exist in your life beyond, you know, a nighttime of TV.

“We’re on strike. We’re talking about very heady things; you know, an existential threat to our livelihoods.” And “it’s kind of nice to just make a pot. It’s a little bit more like I have control over this.”

For Emily Halpern, the strike has provided her an opportunity to work on a deeper, more personal creative level.

A co-screenwriter on “Booksmart” and “80 for Brady” and the ABC-TV series “Black-ish,” she has been writing songs and performing at small venues in Los Angeles including the Hotel Café. “I’ve loved music my whole life and had always wanted to try and just see if I could write songs and perform,” she said.

Halpern, of West Hollywood, first delved into her musical side during the pandemic, putting out an EP, “Carry Me Home.” Once the strike began, she picked up her guitar again. Unlike screenwriting, with music, Halpern is able to explore a more vulnerable side to her art.

“Everything I do in the industry is collaborative to some degree,” said Halpern, who is part of a screenwriting team. “And that’s a wonderful thing. But there has been something nice about this. It’s just my own thing. And so it’s both terrifying and liberating.”

And then there’s Elizabeth Benjamin. “I would say, yes, it’s hard to turn off your creativity,” said Benjamin, a successful Los Angeles writer and producer on shows such as “The Flight Attendant.” “You just can’t be creative on the projects that are making you money.”

She has been refocusing her ingenuity on what she calls “urban homesteading,” tending to her artisanal chickens, amending the soil in her organic garden and planning to re-sand her kitchen. It’s not writing, but after a fashion, it is creating.

“I had this dance teacher who used to say, ‘You always have to fill up the well creatively. It’s your job as an artist to fill yourself up.’ I always took that to heart.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.