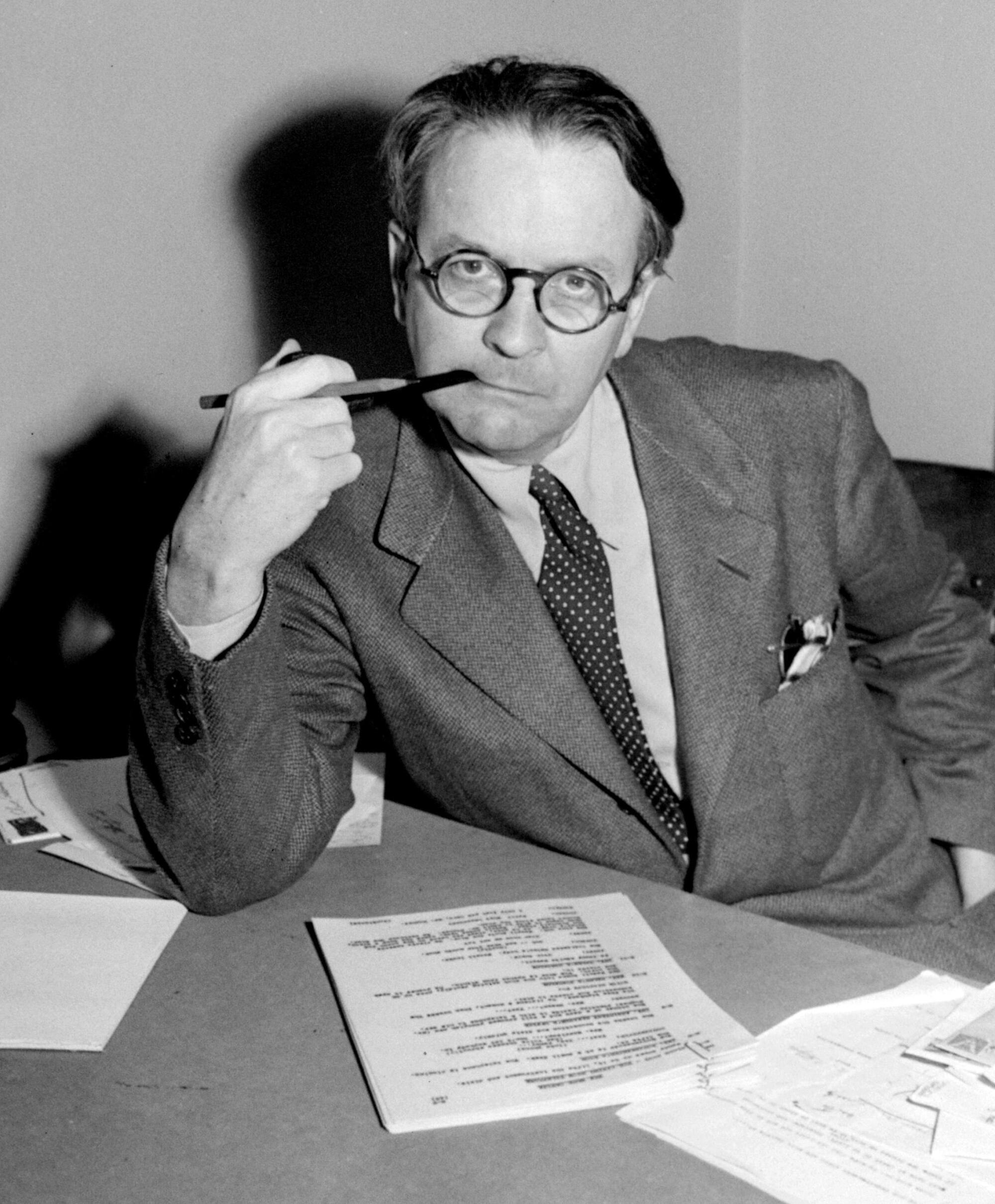

In 1945, barely two years into Raymond Chandler’s career as a screenwriter, the man whose hard-boiled fiction did much to make film noir into an art form had already wearied of the town and its treatment of writers.

“Hollywood is a showman’s paradise. But showmen make nothing; they exploit what someone else has made,” he wrote in an acerbic essay published in the Atlantic.

In barbed zinger after zinger, the man who gave us private investigator Philip Marlowe described Hollywood as a cauldron of “egos,” “credit stealing” and “self-promotion” where scribes were ruthlessly neglected, marginalized and stripped of respect; toiling at the mercy of producers, some of whom, he wrote, had “the artistic integrity of slot machines and the manners of a floorwalker with delusions of grandeur.”

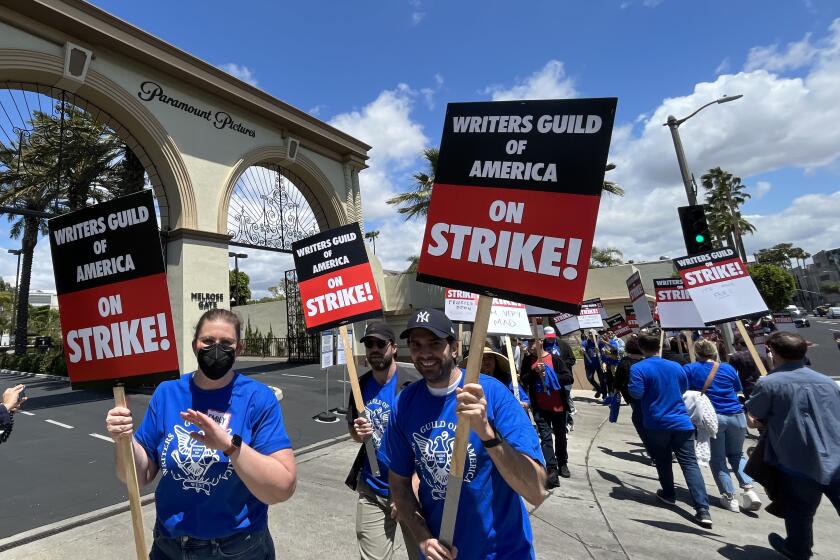

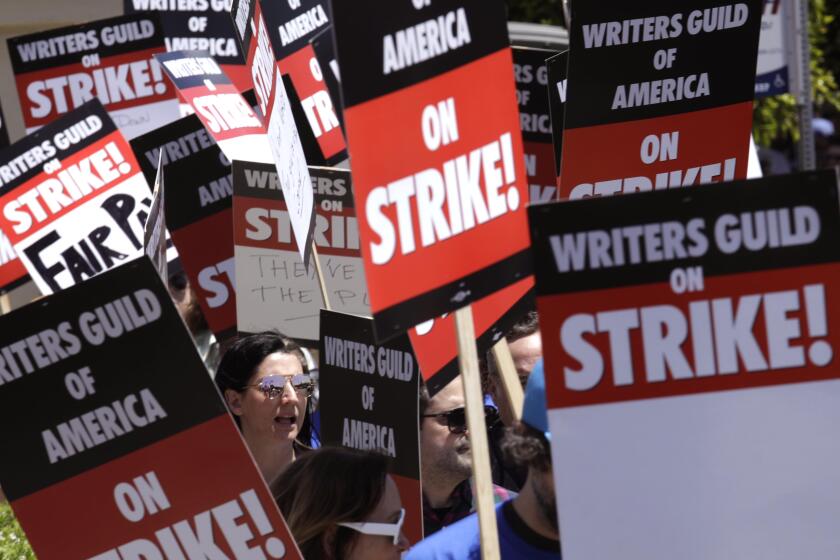

Nearly 80 years after Chandler excoriated the industry, a new generation of scribes says that not much has changed and has taken to the picket lines to denounce the pileup of indignities.

Long unappreciated, writers for the screen big and small complain this time around that they are now not simply undervalued but underpaid too. In the era of Peak TV and the rise of powerful disruptors like Netflix and Amazon, they say profits have ballooned for the studios and their executives who’ve reaped billions, while they’ve been streamrolled — subjected to worsening working conditions and deprived of a sustainable living.

Hollywood’s writers went on strike, but what were the issues that led to the fallout with the studios and streamers. Here are six issues where talks fell apart.

Chandler might as well have been writing about today when he called Hollywood a place where degradations, such as the “incessant bone-scraping revisions imposed on the Hollywood writer by the process of the rule of decree,” were routine — and where a screenwriter’s billing “will be smaller than that of the most insignificant bit-player.”

Chandler concluded that such humiliations were by design, “a deliberate and successful plan to reduce the professional screenwriter to the status of an assistant picture-maker, superficially deferred to (while he is in the room), essentially ignored, and even in his most brilliant achievements carefully pushed out of the way of any possible accolade which might otherwise fall to the star, the producer, the director.”

In many ways, the new fight is about the old fight, and that has always been about respect.

“These struggles have been going on for over a century,” said USC history professor Steven J. Ross, who pointed out that screenwriters first organized in the 1910s.

During Hollywood’s golden age of the 1930s and 1940s, when moviemaking operated under the studio system, the moguls who ruled over the industry exhibited little appreciation for writers or the writing process.

Irving Thalberg, who along with Louis B. Mayer helped make MGM, once famously remarked: “What’s all this business about being a writer? It’s just putting one word after another.’’

Thalberg took the dim view that writers were much like factory workers. Indeed, Thalberg is largely credited with establishing the assembly-line method of screenwriting.

The current writers’ strike is just the latest in Hollywood. Since the 1950s, writers gone on strike eight times.

As novelist-turned-screenwriter P.G. Wodehouse groused in a letter to a friend in 1930, “So far, I have had eight collaborators. The system is that A. gets the original idea, B. comes in to work with him on it, C. makes a scenario, D. does preliminary dialogue, and then they send for me to insert Class and what-not. Then E. and F., scenario writers, alter the plot and off we go again.”

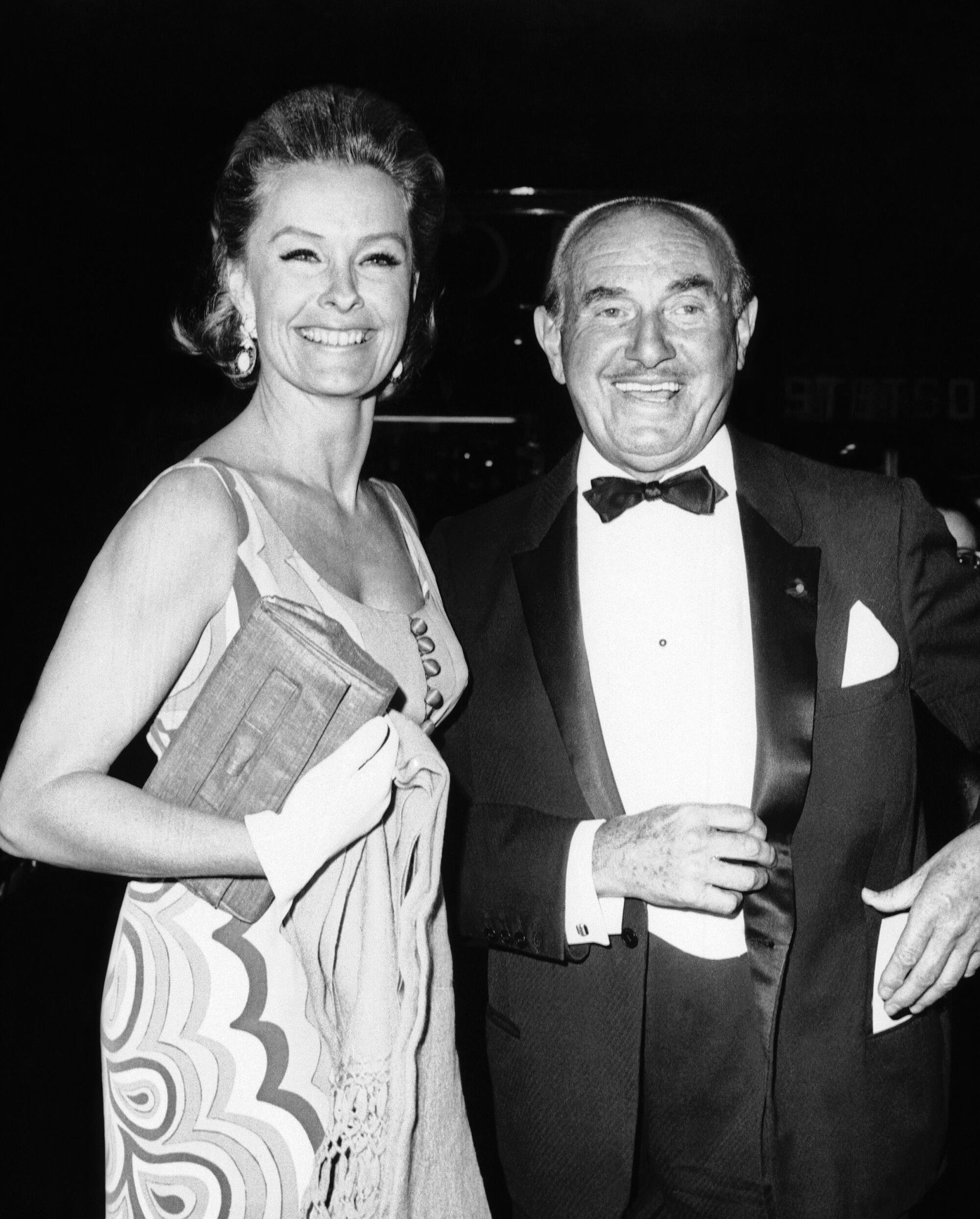

But it was Warner Bros. studio honcho Jack L. Warner who perhaps best summed up the lowly status of writers, calling them: “schmucks with Underwoods.”

(For those unfamiliar with Underwoods, they were once a well-known brand of typewriter. For those unacquainted with a typewriter, it was once a popular machine for writing on paper. And for those not versed in Yiddish, a schmuck is a fool.)

All the same, at the dawn of the “talkies,” the studios were eager for talent to supply dialogue but also prestige. They wooed the most acclaimed Broadway playwrights, authors and journalists of the day to head out west. And they came: Dorothy Parker, George S. Kaufman, Christopher Isherwood, James Agee, Aldous Huxley and Clifford Odets, to name a few. As screenwriters they could make the kind of money that their novels, plays and articles did not.

But they too looked down upon the industry and heaped scorn upon the work.

In 1925, Herman Mankiewicz — who went on to co-write “Citizen Kane” in 1941 — famously sent a telegram to his friend Ben Hecht, a Chicago Daily News reporter, telling him the Brinks truck would practically back up at his front door in Hollywood: “Millions are to be grabbed out here and your only competition is idiots.”

Commenting on the lucre to be had, Parker said, “It isn’t real money. It isn’t. I think it’s made of compressed snow. It just melts in your hands.”

Hollywood writers on Tuesday formed picket lines in L.A. and New York after the Writers Guild of America called a strike to demand better pay from streaming and improved working conditions.

Parker, the master of acid one-liners, came to Hollywood in the mid-1930s with her husband, Alan Campbell. The pair got a contract with Paramount and together made $1,250 a week, later bumped up to $5,000 — an exorbitant sum during the Great Depression.

Parker helped write “A Star Is Born” in 1937, and many suspect she had a hand in Frank Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life.” But she wrote scads of forgettable films and thought little of the art of the screenplay, once saying, “You don’t need any talent — the last thing you want is talent.”

While these writers earned buckets of money, they got little regard. In scores of letters and other missives, they regularly complained of being snubbed, rewritten and their dignity trampled by actors, producers and directors alike.

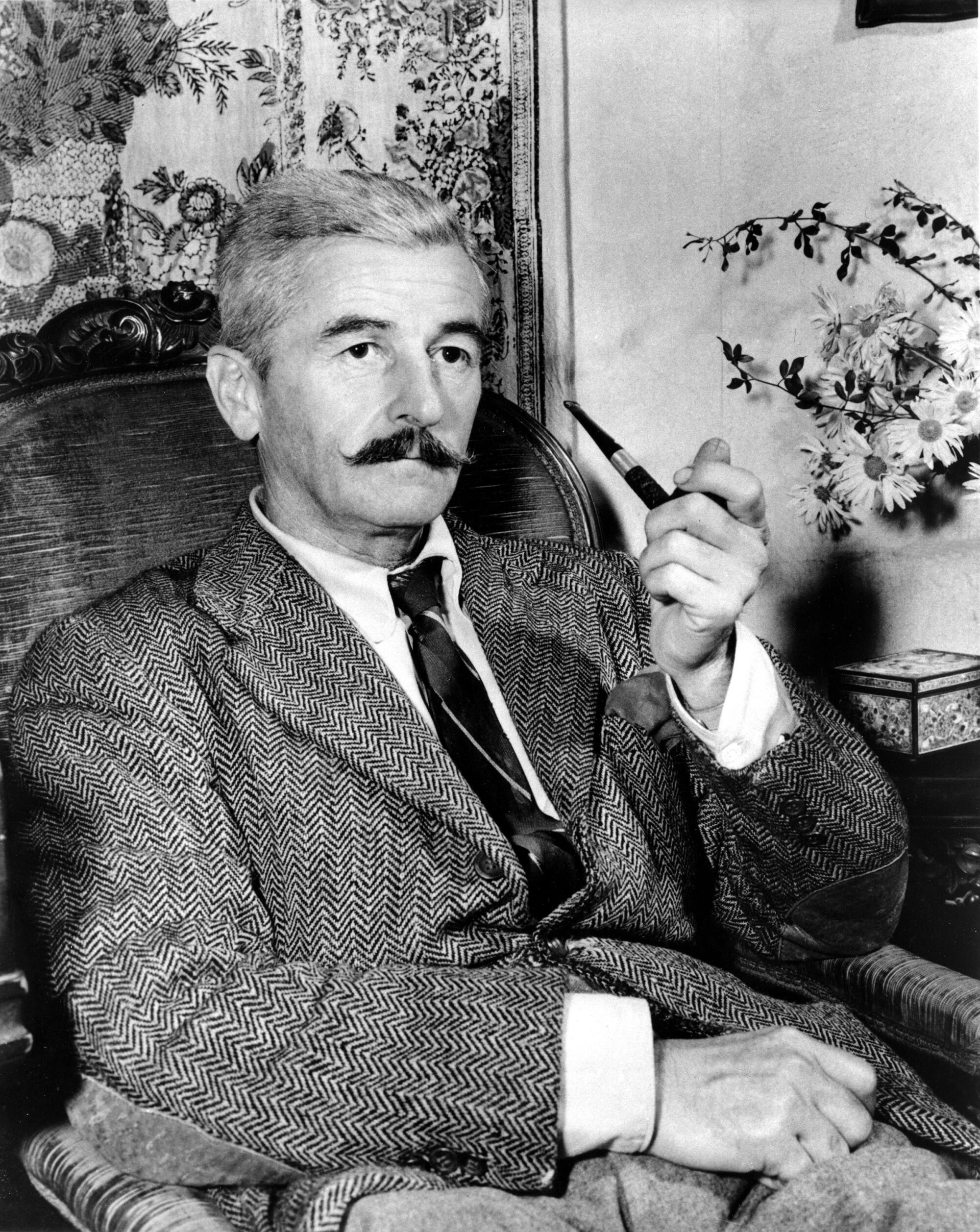

Between 1932 to 1954, Nobel laureate William Faulkner worked on some 50 films, including the adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s “To Have and Have Not” and Chandler’s “The Big Sleep.” By most accounts, however, he hated the work, spent much of his time drinking and had an affair with director Howard Hawks’ secretary and script supervisor Meta Carpenter.

Summing up his stretch as a contract screenwriter for MGM, 20th Century Fox and others, Faulkner is reported to have said, “The writer in America isn’t part of the culture of this country. He’s like a fine dog. People like him around, but he’s of no use.”

When F. Scott Fitzgerald was asked to return to Hollywood in 1935, after two earlier failed stints, he wrote to his agent, Harold Ober, “I hate the place like poison with a sincere hatred.”

Two years later, Fitzgerald arrived in sun-splashed Los Angeles with a $1,000-a-week contract (later extended and increased to $1,250) with MGM. He lasted 18 months.

Among the many indignities he suffered, Fitzgerald was dropped from both “Gone With the Wind” and “The Women.” In the case of the latter, the studio found his dialogue did not meet the standard for cattiness.

In 1937, Fitzgerald was brought in to take over the script for “Three Comrades,” an adaptation of the popular novel by Erich Maria Remarque.

When he handed his draft to Joseph Mankiewicz, the producer paired him up with cinema veteran Edward E. Paramore Jr. After they worked on the script for five months, Mankiewicz went in and rewrote much of it.

Humiliated, Fitzgerald fired off a furious letter, “To say I’m disillusioned is putting it mildly. For nineteen years, with two years out for sickness, I’ve written best-selling entertainment, and my dialogue is supposedly right up at the top.”

He then pleaded with Mankiewicz to “restore the dialogue to its former quality,” before saying, “Oh, Joe, can’t producers ever be wrong? I’m a good writer — honest.”

Hollywood writers formed picket lines in L.A. and New York after the Writers Guild of America called a strike for better pay and working conditions.

Quentin Tarantino was less charitable when Oliver Stone completely rewrote his screenplay for the 1994 film “Natural Born Killers.” Tarantino distanced himself from the project, took only a “story by” credit and publicly said he’d never seen the full version of the film. Stone would go on to blame Tarantino’s condemnations for why the film was largely a critical failure.

In a visual medium such as film or television, the writer is often viewed as an invisible spoke in a very big wheel. As even Fitzgerald acknowledged: “It was an art in which words were subordinate to images, where personality was worn down to the inevitable low gear of collaboration.’’

After all, while most regular consumers of film and TV know who directors Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg and perhaps even famed costume designer Edith Head are, how many can name a scriptwriter?

Emma Thompson is better known as an actress than a writer even though she won an Academy Award for screenwriting for her adaptation of “Sense and Sensibility.” She decried the culture in Hollywood that devalues writers, telling the Guardian there is a “merciless gag” in which scriptwriters are “the lowest of the low.”

“Audiences don’t know somebody sits down and writes a picture; they think the actors make it up as they go along.”

— Character of Joe Gillis in “Sunset Boulevard”

The plight of the Hollywood writer is now part of the cultural fabric. Even in movies about movies, the lowly status of writers is frequently a featured plot point.

Take the 1950 Billy Wilder classic, “Sunset Boulevard.” The film opens with the dead body of struggling screenwriter Joe Gillis floating facedown in a pool. The story of Gillis, who has become ensnared in the fantasy world of forgotten film star Norma Desmond, is told in flashbacks. At one point he says in exasperation: “Audiences don’t know somebody sits down and writes a picture; they think the actors make it up as they go along.”

In the Coen brothers’ 1991 black comedy “Barton Fink,” the title character, another screenwriter beset by a litany of struggles, yells out, “I’m a writer, you monsters! I create! I create for a living! I’m a creator! I am a creator!”

Adding insult to injury, for many the image of the Hollywood writer is not only of someone who does little more than casually toss together some sentences, but is paid extravagant sums to do so.

Certainly, the massive nine-figure deals that Ryan Murphy and Shonda Rhimes minted with Netflix have done much to reinforce this conceit. As did the $60-million deal that “Fleabag” creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge struck with Amazon that, three years later, has yet to yield a single new show.

The reality, however, is starkly and vastly different.

Back in 1945 when a movie critic derisively asserted, “how dull a couple of run-of-the-mill $3,000-a-week writers can be.” Chandler took him to task, writing, “I hope this critic will not be startled to learn that 50 per cent of the screenwriters of Hollywood made less than $10,000 last year, and that he could count on his fingers the number that made a steady income anywhere near the figure he so contemptuously mentioned.”

The 2023 writers’ strike is over after the Writers Guild of America and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers reached a deal.

Since 1952, Hollywood writers have gone on strike eight times. Each time has been a clarion call for respect.

“I think Hollywood has a history of undervaluing writers,” said Elizabeth Benjamin, a Writers Guild of America member who has been out picketing. A successful writer and producer on shows such as “Dead to Me” and “The Flight Attendant,” she added, “It’s the attitude that we simply provide a service like a carpenter. But we are the creators of the content that they use to make a fortune.”

And so the quest for respect is one Hollywood story sure to have many sequels. As Chandler wrote in 1945, “This struggle is still going on; in a sense it will always go on, in a sense it always should go on.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.