Ask a Hollywood studio executive about the state of the entertainment business these days, and many will say, “Don’t ask.”

Firms such as Netflix, Warner Bros. Discovery and Disney have laid off hundreds of employees. Companies are under pressure from Wall Street to cut costs and deliver reliable profits while they make risky investments in streaming. Meanwhile, talk of a recession percolates every day.

The uncertain economic landscape is complicating the already-fraught contract negotiations between the Writers Guild of America and film and TV studios as they try to hammer out a new deal this month.

Failure to reach a new agreement could lead to the first strike by Hollywood writers since the disruptive work stoppage that hit the industry in 2007-2008.

Streaming has transformed television and led to a surge in content, but it also has squeezed Hollywood writers. Five Writers Guild of America members share their stories.

“It’s going to be a tough environment for them to come to a deal quickly because of the dynamics with studios having to make some cost cuts,” said David Smith, a professor of economics at Pepperdine University’s Graziadio Business School. “We’re still in this uncertain period about where digital streaming is going to end up.”

Adding to the complexities, the makeup of the trade group representing the major film and TV studios and networks — the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, or AMPTP — has changed dramatically since the last WGA strike in 2007-2008. With tech giants now in the mix, some members have competing priorities that could affect their willingness to hold the line as screenwriters demand more money from their work on streaming series, according to people familiar with the talks who were not authorized to speak publicly.

Deep-pocketed Amazon and Apple, for example, are looking to keep their relatively new film and TV operations humming to fuel their streaming businesses but are less accustomed to dealings with the entertainment unions than the more traditional members, like Warner Bros. and Disney.

Others close to the negotiations push back on the notion that the alliance is fractured. They note that despite their divergent business interests, all the major studios — with the exception of Sony — have a shared interest in growing their burgeoning streaming businesses.

“I do think there’s an interest on the part of streaming companies to continue to make gains in this industry,” Smith said. “They probably don’t want their momentum to stop with an extended work stoppage. And they’re flush with cash so they might be willing to give up a little bit more to the writers.”

The 2007-08 writers’ strike, and lingering mistrust between big media companies and their Hollywood workers, has cast a long shadow over current WGA contract talks.

The AMPTP declined to comment for this story.

For their part, the writers are seeking improvements such as a minimum number of scribes hired for TV shows, taking aim at the so-called “mini-rooms” becoming increasingly common in the streaming era. They also want an increase in residuals for streaming series, many of which do not benefit from the “back end” of traditional television, in which shows earn money from syndicated sales to TV stations and cable networks.

The WGA and AMPTP began talks on March 20 to come up with a deal before the current contract expires May 1. The WGA has asked its 11,500 members to vote to authorize a strike, a standard procedure as the union looks for leverage in the talks.

The union has dismissed talk of the studios’ economic hardship as a convenient, frequently cited excuse to justify not paying writers what they deserve.

“Every three years, writers are told why the current conditions make addressing their issues untenable,” the WGA said in a statement to The Times. “The current conditions now are that the studios remain extremely profitable, while writers are losing ground. In this negotiation, writers are demanding protections that address all the ways the studios have cut pay, squeezed more work into less time or onto fewer writers, and demanded more work for free.”

The guild argues that many of the studios’ wounds are self-inflicted. The rapid rise of Netflix sent companies such as Comcast, Paramount, Disney and others scrambling to catch up with heavy investments in streaming. Recently, that shift has come under the unforgiving glare of Wall Street analysts after Netflix’s once-torrid subscriber growth sputtered.

The writers say that’s not their problem.

“It’s not for writers to pay for the poor decision-making of companies who decide to pursue expensive mergers or take on large amounts of debt,” said the WGA’s chief negotiator, Ellen Stutzman. “Those are short-term things that will change and we have to negotiate a contract that will live on for decades.”

Unscripted programming is once again poised to serve as a stopgap for networks and streaming services, but since the last strike, it has matured into a formidable genre.

A WGA analysis said entertainment operating profits for AMPTP members rose from $5 billion in 2000 to $28 billion in 2021, which is down from $30 billion in 2019. Studio revenue has risen from $155 billion in 2013 to more than $220 billion in 2022. And spending on original content for streaming is expected to reach $19 billion this year — nearly four times the spending level in 2019.

The union’s fighting words are one reason why the studios are preparing for the worst. Producers say privately that the market for scripted programming has already softened because networks don’t want to tie up money in projects that could be hobbled by a lengthy strike.

Studios are terminating projects that have been in active development or are about to commence production, said Elsa Ramo, managing partner of entertainment law firm Ramo Law PC.

In the run-up to the 2007-2008 strike, studios and producers stockpiled scripts so they’d have something to run. Companies are once again hedging against a potential work stoppage by producing additional episodes this year and banking them for later.

But buyers may be less panicked this time around because of changes in how consumers watch in the streaming era.

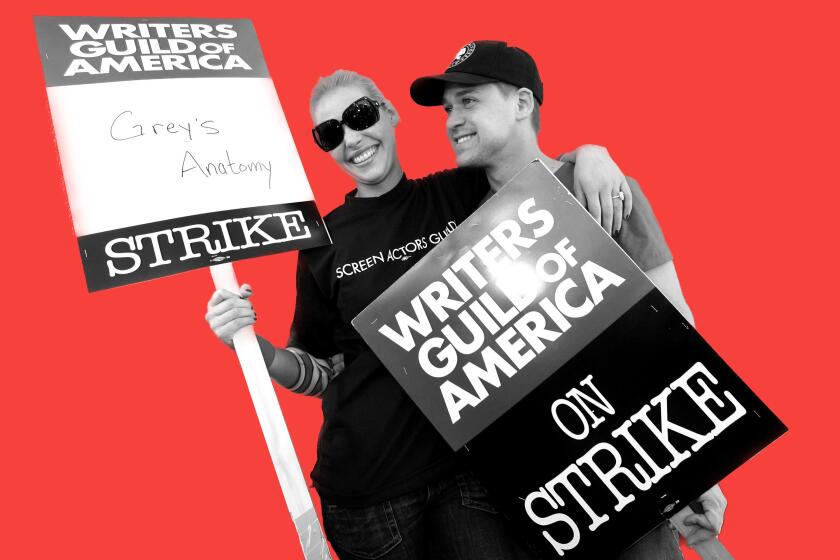

The call for a possible strike comes amid growing concern that writers will stage a walkout in a dispute over streaming compensation.

While big home-grown hits such “Stranger Things” on Netflix and Amazon’s “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” get streaming customers into the tent, once inside they discover a massive catalog of older shows providing thousands of hours of programming. It’s how decades-old, long-running series such as “Friends,” “The Office” and “Seinfeld” became hot again.

Consumers may not feel the impact of a strike until the traditional television season begins in the fall and they don’t find new episodes of their favorite shows.

Amazon and Apple are reportedly set to each spend $1 billion annually to produce movies for theatrical release. (It was the deep pockets of tech players that drove Rupert Murdoch to sell his TV and movie production assets to Disney in 2019.)

The ripple effects of a strike would be significant. Without writers, thousands of other employees involved in other aspects of TV and movie production will have to sit and wait for the two sides to come to an agreement.

But there are other economic reasons why the studios would be willing to sustain a strike. If a job action lasts several months, studios can cancel high-priced contracts with writers citing circumstances beyond their control, as many of them have so-called force majeure clauses.

“No one will say it,” said one producer and former network executive, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “But I think they’re secretly happy if there is a strike because it allows them to get out of some of their overall deals.”

Times staff writer Meg James contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.