Regal Cinemas parent company seeks bankruptcy protection in box office drought

Cineworld Group, the world’s second-largest movie theater operator and parent company of Regal Cinemas, has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection from creditors amid a severe box office downturn.

The London-based business on Wednesday said the company and its subsidiaries had started proceedings in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of Texas in a bid to reduce its debts. Cineworld said it had secured $1.94 billion in new financing from existing lenders to ensure its operations continue during the reorganization and warned that its debt restructuring will result in the “very significant dilution” of shareholders’ investments.

“The pandemic was an incredibly difficult time for our business, with the enforced closure of cinemas and huge disruption to film schedules that has led us to this point,” Cineworld Chief Executive Mooky Greidinger in a statement. “This latest process is part of our ongoing efforts to strengthen our financial position and is in pursuit of a de-leveraging that will create a more resilient capital structure and effective business.”

The filing marks a dramatic retreat for the fast-growing Regal, which has long been an iconic theater operator in Southern California and also owns the Edwards and United Artists cinema brands.

Older audiences are gone? Disney+ trained families to stream and stay home? Not so fast.

But, like other theater operators, the cinema giant struggled to navigate through the headwinds that have buffeted the theatrical industry amid the COVID-19 pandemic and Hollywood’s rapid march toward streaming and watching movies at home.

Cineworld previously signaled that it was exploring strategic options to contend with its substantial debt load, as a promising start to the all-important summer movie season gave way to dramatically dwindling box office returns.

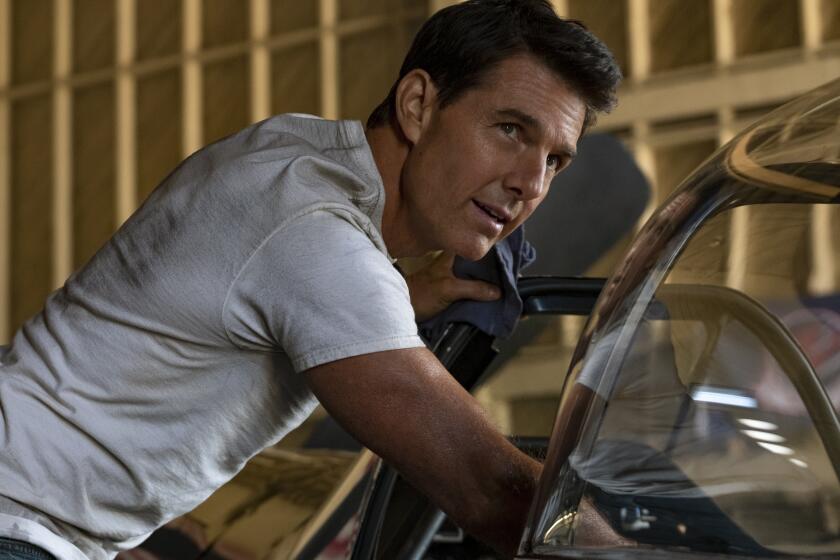

Hollywood productions such as “Top Gun: Maverick,” “Jurassic World Dominion” and “Minions: The Rise of Gru” brought droves of patrons back to cinemas, giving the industry a much-needed confidence boost.

Lately, however, there’s been little for theater owners to celebrate.

Ticket sales fell off dramatically in August after the mediocre debut of Sony Pictures’ Brad Pitt action flick “Bullet Train.”

There are few, if any, big, all-audience movies coming from studios until the October release of “Black Adam,” starring Dwayne Johnson as a DC Comics antihero. Multiple factors contributed to the thin release schedule, including COVID-19 production delays, a logjam of unfinished films at visual effects houses and the transition of many movies to streaming services.

The box office success of “Top Gun: Maverick” seems so long ago as Regal and other chains face financial troubles.

Movie theater owners were walloped by the pandemic, when government regulations forced cinemas to close for months.

And Cineworld faced a serious debt burden. It reported a net debt of $10.35 billion as of June 22, or $5.16 billion excluding lease liabilities, according to the bankruptcy filing.

The company posted revenue of $1.8 billion last year, compared with $4.4 billion in 2019, the year before the global public health crisis struck, according to regulatory filings.

Cineworld on Aug. 17 said it was in “active discussions” with stakeholders to explore options for finding liquidity or restructuring its balance sheet.

“Despite a gradual recovery of demand since reopening in April 2021, recent admission levels have been below expectations,” the British company said then. “These lower levels of admissions are due to a limited film slate that is anticipated to continue until November 2022 and are expected to negatively impact trading and the group’s liquidity position in the near term.”

During its restructuring, the company said it expected to operate its business as usual with vendors, suppliers and employees being paid.

Cineworld is planning to submit a reorganization plan to the court and exit Chapter 11 in 2023, it said. The plan includes renegotiating cinema lease terms with its U.S. landlords, it said.

It said it expected its shares to continue to trade on the London Stock Exchange.

It’s not the first time Regal has found itself in trouble with creditors.

Regal Cinemas was founded in 1989 in Knoxville, Tenn., and rode a wave of megaplex and multiplex construction in the 1990s.

As the industry faced a glut of giant theaters after years of overdevelopment, Regal declared bankruptcy in 2001 amid a wave of consolidation in the exhibition business. Regal completed its Chapter 11 reorganization and emerged from bankruptcy in 2002 under the ownership of an investor group led by billionaire Philip Anschutz, a developer of L.A. Live with a state-of-the-art Regal multiplex.

In 2017, Regal agreed to be sold to Cineworld. The deal valued Regal at $3.6 billion.

Cineworld is not the first theater operator to seek bankruptcy protection since the pandemic, but it is the largest to do so.

Pacific Theatres and ArcLight Cinemas last year declared Chapter 7 bankruptcy in order to liquidate holdings. Leases to former ArcLight and Pacific theaters have been picked up by larger chains — including Regal, which took over the ArcLight at the Sherman Oaks Galleria last year.

Austin, Texas-based Alamo Drafthouse filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, as did Dallas-based Studio Movie Grill. Both specialty chains later emerged from bankruptcy.

The pandemic aftereffects have been disruptive for moviegoers in Los Angeles, the world’s film capital.

Laemmle Theatres gave up the lease at its Playhouse 7 location in Pasadena, which was taken over by Landmark Theatres. Famous cinephile destinations, the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood and the Vista Theatre in Los Feliz, have been closed since March 2020 but are expected to reopen eventually.

AMC Theatres, the largest theater operator, also carries a debt burden of more than $5 billion and is dealing with the same box office climate as Regal.

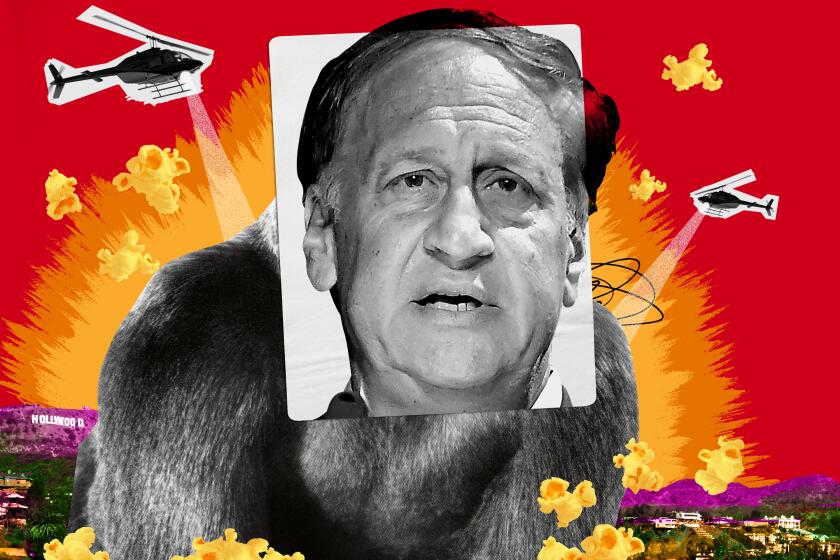

Adam Aron rode the meme stock wave to rescue AMC. With his embrace of NFTs and cryptocurrency, plus a campy Nicole Kidman ad, he’s a polarizing figure.

However, an influx of highly enthusiastic retail investors — colloquially known as “apes” — helped save the Leawood, Kan., company from bankruptcy by piling into the stock and promoting it online, egged on by Chief Executive Adam Aron. AMC buttressed its balance sheet by selling shares at the elevated prices.

Times staff writer Anousha Sakoui contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.