Trump refuses remote debate with Biden. Nixon and Kennedy did one 60 years ago today

If President Trump does eventually agree to a virtual debate with his Democratic opponent, Joe Biden, it won’t be the first showdown between two presidential candidates in different locations.

The Commission on Presidential Debates wanted the event that was originally scheduled for Thursday — now officially canceled — to have the candidates participate remotely because of Trump’s recent bout with COVID-19. The president refused, insisting his health was fine for an in-person appearance.

Trump and his surrogates also suggested that a remote setup would allow Biden to cheat and “read the answers off a computer screen.” Whether the two candidates will appear at the debate scheduled for Oct. 22, in person or virtually, remains uncertain.

While this conflict and disruption are consistent with the often bizarre 2020 campaign, the only other presidential debate for which the candidates appeared in separate locations — 60 years ago today — also came with its share of distrust and suspicion.

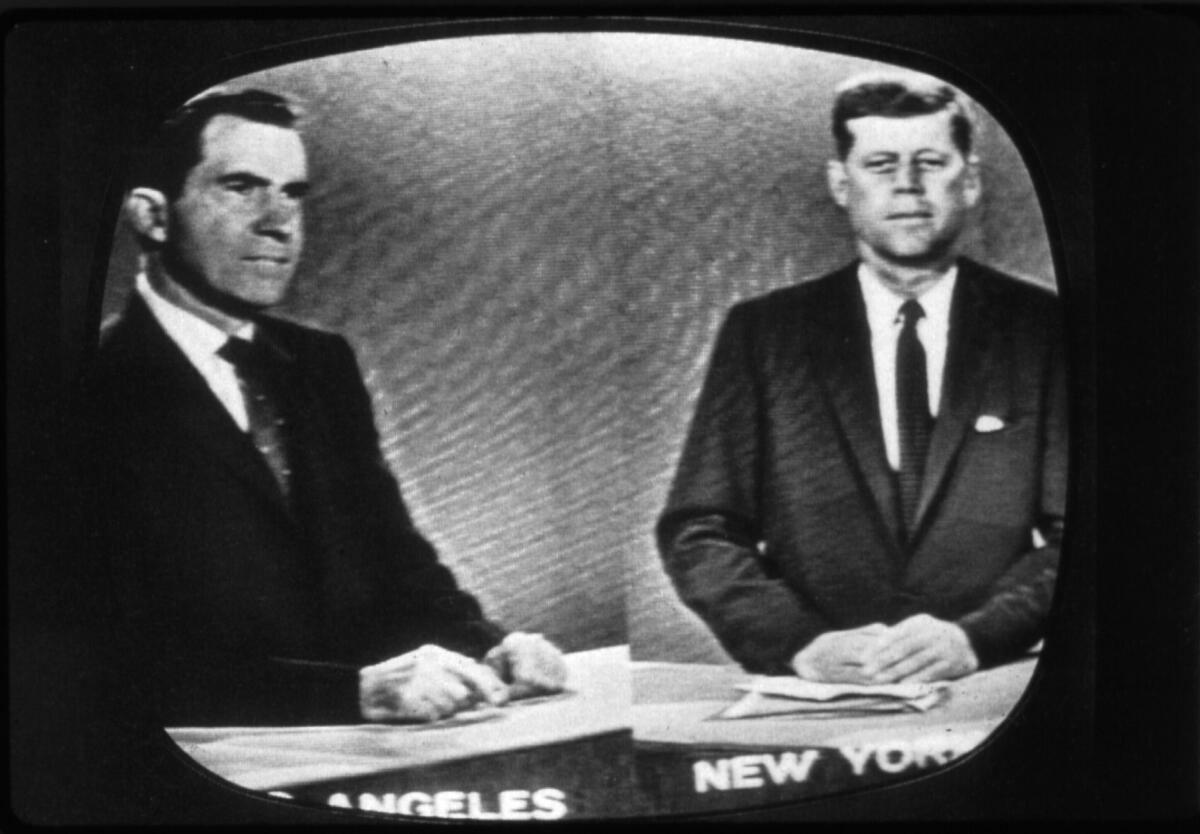

In 1960, Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy brought presidential politics into the television era when they agreed to a series of joint appearances that were simulcast across the three major broadcast networks: ABC, CBS and NBC. The candidates committed to four meetings — which became known as the “Great Debates” — over four weeks in the fall of that year.

But the pursuit of the 270 electoral votes needed to win the presidency required a lot of time pressing the flesh in a lot of places for Nixon, then the Republican vice president, and Kennedy, the Democratic junior senator from Massachusetts.

With the election less than a month away, the impasse could cost Trump a crucial last chance to close the gap with Biden.

“In 1960 over 20 states were considered real battlegrounds, as opposed to about half that today,” said Larry Sabato, director of the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia. “The candidates had to move around a lot.”

The first debate took place at the studios of the CBS station in Chicago on Sept. 26, 1960, followed by a second meeting at NBC’s Washington bureau on Oct. 7. The third event was scheduled for Oct. 13, when the two candidates planned to be on separate coasts.

“When the negotiators for the campaigns realized the candidates would be far apart on a preferred day, it’s my understanding that the TV execs effectively said, ‘We can do this with new technology,’ and maybe they even saw this as a gimmick,” Sabato said.

Satellite delivery of TV signals did not begin until 1962, but television networks were able to broadcast live pictures from different locations using AT&T’s phone lines. Millions of viewers saw NBC use a version of this technology every night on “The Huntley-Brinkley Report,” which frequently switched between the network’s New York and Washington studios.

The campaigns agreed to a broadcast in which the candidates would interact from separate locations. Kennedy appeared from ABC’s New York studio on West 66th Street in Manhattan. Nixon was in the network’s Los Angeles studios at Prospect Avenue and Talmadge Street.

ABC took painstaking measures to make sure neither candidate had an advantage. The network built identical sets 3,000 miles apart — 35 feet wide and 12 feet deep with brown wood paneling and an American flag in the background. A can of the paint used on Kennedy’s desk in New York was even flown to Los Angeles and applied to Nixon’s desk.

Extra cameras and audio equipment were installed in both cities to make sure neither candidate would be at a disadvantage in the event of a technical failure.

Trump refused to debate Biden in a virtual format that had been changed by the independent debate panel after the president contracted COVID-19.

The separate locations also allowed each candidate to control his own studio temperature, which had been a source of conflict in the previous two debates. Nixon, who had a tendency to perspire, had his L.A. set chilled to around 60 degrees, while Kennedy kept his New York quarters at 72 degrees.

The moderator, ABC News anchor Bill Shadel, and a panel of four journalists from NBC News, CBS News, a magazine called the Reporter, and the New York Herald Tribune newspaper, gathered in a separate Los Angeles studio where the control room was also based. The candidates could see the questioners and each other only through TV monitors.

The twin sets were intended to create a seamless look for what ABC promoted as “the most technically complicated broadcast in history.” But Nixon and Kennedy appeared on a split screen together for only about 15 seconds, when they were introduced to viewers by Shadel.

The one-hour broadcast came off without any technical glitches. But charges of rule-breaking arose immediately after it ended.

The two campaigns had a spoken agreement that the candidates would not have any prepared notes on set. But a few minutes before the debate began, Nixon caught a glimpse of a TV monitor showing Kennedy shuffling at least two stacks of paper at the desk where he stood in New York.

Continuous coverage of the Watergate hearings in 1973 drew big audiences and viewer contributions. It also led to the creation of the “PBS NewsHour.”

When the issue was raised after the debate, Kennedy’s press secretary Pierre Salinger said the papers were not notes, but rather copies of correspondence from then-President Eisenhower to a senator, from which the candidate quoted. When one of the pool reporters covering the event noted that there were as many as eight pages laid out in front of Kennedy, Salinger conferred with his boss and found that Kennedy also had photostat copies from a book by a former Army chief of staff and some quotes from the late Secretary of State John Foster Dulles.

John Daly, vice president of news and public affairs for ABC, said the networks believed that the use of notes was not permitted. But Daly — who was also the moderator of the CBS quiz show “What’s My Line?”— added little clarity when he issued a statement that said he could “only presume that the verbatim text of public documents was not included in the restrictions” and as a result did not intervene.

Kennedy also offered a rationale. “If I’m going to quote the president of the United States on a matter of national security, he should be quoted accurately,” he told the Associated Press.

Nixon reportedly appeared agitated over the matter after the debate. But with no Twitter or cable news to fan the flames in 1960, he simply grumbled to reporters that the rules needed to be more clear the next time the two candidates met — on Oct 21. The vice president exited the studio and headed with his wife, Pat, and an entourage to dinner at Perino’s, a Wilshire Boulevard eatery popular with celebrities and politicians.

“It never became much of an issue,” Sabato said. “A tempest in the debate teapot.”

Historians regarded the long-distance face-off as Nixon’s best performance of the four debates, but the events overall clearly benefited the more television-savvy Kennedy, who won the election.

Nixon — who was elected to the White House eight years later — did become more comfortable with the trappings of the still nascent medium.

On Friday, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi proposed creating a commission that would determine whether a president is incapacitated. We need it.

He used the services of Claude Thompson, NBC’s top makeup artist in Hollywood (he worked regularly with Bob Hope), for his Los Angeles appearance. Many pundits attribute Nixon’s perceived loss of the first debate a couple of weeks earlier to his refusal to wear makeup, making him appear pallid and in need of a shave compared to his tanned and youthful opponent.

Even during what is now looked back on as a more genteel era in presidential politics, there was no shortage of conspiracy theories. A TV critic for Variety who monitored the third debate said Nixon’s receding hairline looked more robust than usual and insisted he must have been wearing a toupee.

Still, that remote debate 60 years ago worked — with 64 million viewers, it was the second most watched of the four Nixon-Kennedy matchups. Presidential historian Michael Beschloss believes a health crisis is a compelling enough reason to try it again.

“In the midst of a ruinous pandemic, the wisest approach would always be to stage a debate remotely,” Beschloss said, “just as Kennedy and Nixon did successfully in 1960.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.