Nixon hated PBS, but his Watergate scandal gave the fledgling network a major hit

Fifty years ago this week, the Public Broadcasting System was launched, giving another viewing choice to a TV audience that grew up with the three-network hegemony of ABC, CBS and NBC.

Nonprofit educational TV stations had been around since the mid-1950s, and many of them shared their locally produced programs such as “The French Chef” with Julia Child. It was the formation of PBS in 1969 and its official launch on Oct. 5, 1970, that united those outlets into a network that aired programs across the country simultaneously, giving them national clout.

While the service brought Child and innovative programs such as “Sesame Street” to wider audiences, the early years of PBS were fraught, largely due to a conflict over whether the service should be in the news business. It did not help that PBS was dependent on government funding during the presidency of Richard Nixon, whose hostility and distrust of the media is only rivaled by the current occupant of the Oval Office.

But a big hit show can change everything for a television network. For PBS, it was the Watergate hearings.

By the time PBS went on the air, Nixon was already at war with the TV news divisions he believed were biased against him. His administration even issued threats about denying broadcast license renewals for TV stations if they failed to get in line. He did not want another national news outlet criticizing his presidency, especially one receiving federal funding.

“I think it was primarily the fear of a fourth, as he saw it, ‘liberal’ network,” said Robert MacNeil, the founding anchor of public television’s nightly newscast “PBS NewsHour.”

There was even dissent over providing news among the operators of local public TV stations, who were content with offering largely controversy-free educational and cultural programming for their communities. “It was widely believed in the educational television world that to introduce news or public affairs would create such animosity that funding would dry up,” MacNeil recalled.

In the early 1970s, information-hungry TV viewers largely depended on the three networks’ half-hour evening newscasts such as the “CBS Evening News With Walter Cronkite.” Live, continuous coverage of breaking news events — now a staple of cable news and the internet — was rare. Washington coverage largely consisted of journalists delivering short reports while standing in front of the White House.

In May 1973, a Senate select committee opened hearings on the activities of Nixon’s reelection campaign, less than a year after the bungled break-in at Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate complex in Washington.

While the inquiry that eventually revealed the involvement of the president’s reelection committee in the break-in and the cover-up by Nixon was of vital importance, the commercial TV networks were in a quandary over how much of the hearings to present live. Gavel-to-gavel coverage meant preempting regular programming and losing advertising revenue.

At one point, ABC, CBS and NBC went to a daily rotation of continuous coverage; one network showed the hearings while the others stuck to their game shows and soap operas.

But for noncommercial PBS, the hearings were an opportunity. For 47 days and nights in 1973, the service covered every minute of the proceedings and, for viewers who missed the ongoing daytime saga in that pre-DVR era, reran them in prime time. This created the foundation for PBS’ nightly news program “The MacNeil-Lehrer Report,” which exists today as the “PBS NewsHour.”

“Going wall to wall and covering every minute of the Watergate hearings really helped put PBS on the map,” said Judy Woodruff, the current anchor of the program.

MacNeil had been a veteran journalist with the BBC; during an earlier stint with NBC News he provided on-the-scene reporting of the assassination of President Kennedy in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963. He first joined PBS as host of its weekly discussion program “Washington Week In Review” and was slated to cover the 1972 presidential campaign for the new network alongside Sander Vanocur, who had also worked at NBC.

But Nixon viewed Vanocur as an acolyte of Kennedy, who had defeated him in the 1960 presidential race. The administration led a campaign to discredit the hiring of the anchors, leaking stories about their salaries that were being paid by taxpayers ($65,000 for MacNeil and $85,000 for Vanocur — more than the vice president or the chief justice of the Supreme Court). The White House called for cuts to the Corp. for Public Broadcasting, the government funding arm for PBS.

Vanocur quit, and the plans for covering the 1972 campaign never came to fruition. But when the Watergate hearings were scheduled, PBS received enough support from its stations to cover them.

Jim Karayn, a PBS executive from Los Angeles, teamed MacNeil up with Jim Lehrer, a former Dallas newspaper journalist. Lehrer had been working behind the scenes in the PBS public affairs unit, where his duties included getting stations to run a program about venereal disease, a topic commercial networks declined to cover.

From “Downton Abbey” to Carl Sagan, Julia Child to “The Civil War,” PBS — now celebrating its 50th anniversary — is as influential as ever.

Together the duo logged hundreds of hours on the air during the hearings, which brought dramatic exchanges into the country’s living rooms on a daily basis.

The real-time drama — including White House counsel John Dean’s statement that there was “a cancer on the presidency” and Nixon aide Alexander Butterfield’s revelation that a recording system was installed in the Oval Office — enthralled audiences during the day. Sen. Howard Baker’s question — “What did the president know and when did he know it?”— is as memorable as a line from a classic film.

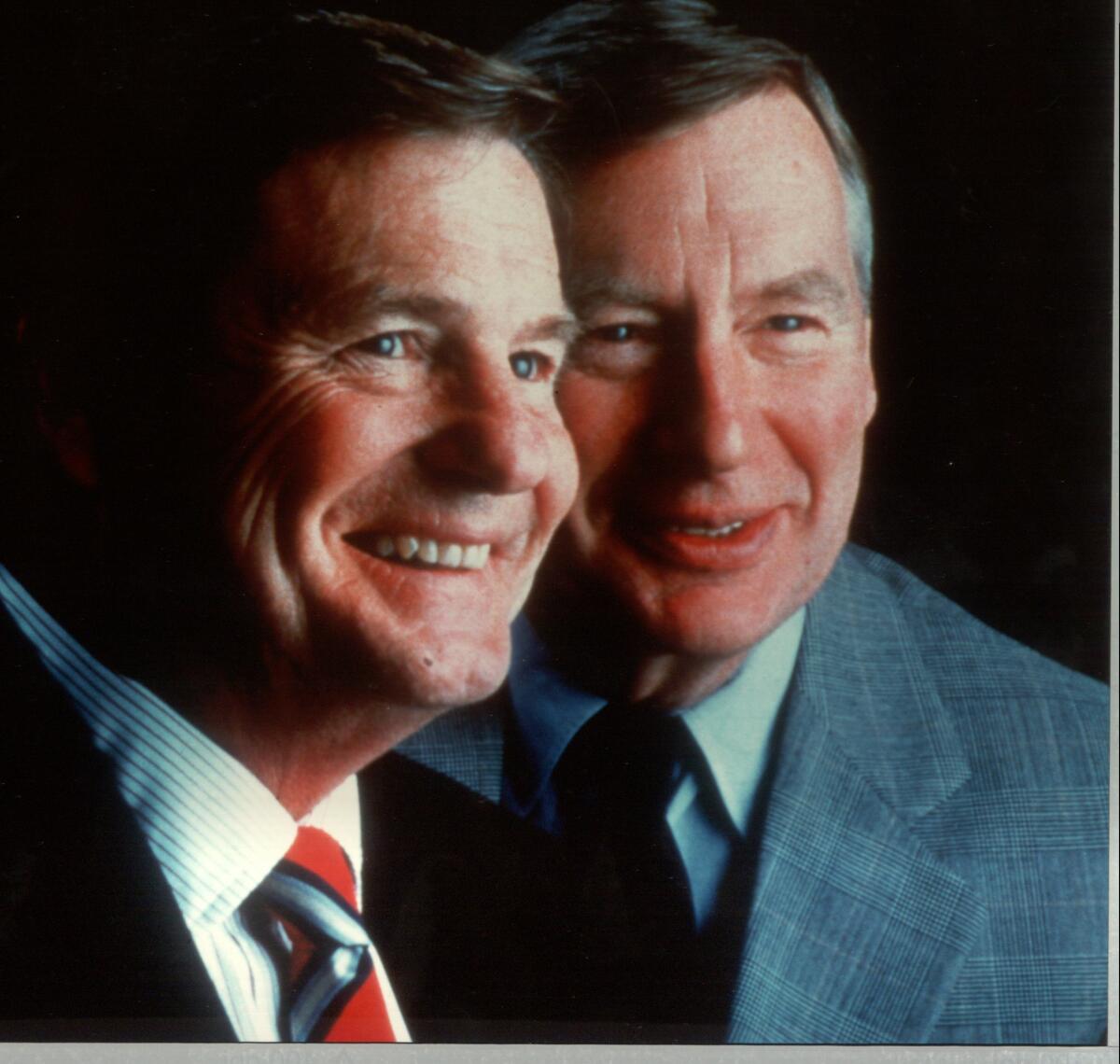

MacNeil and Lehrer were on the air day and night to provide commentary. MacNeil, a Canadian who spoke in a clipped, erudite manner and Lehrer, a Kansas native with a soft drawl from his years in Texas, blended splendidly for a team that came together by accident. They became close friends as well.

Viewer response was tremendous. The stations’ ratings shot up and contributions from viewers poured in. Meanwhile, viewers writing to the commercial networks complained how the coverage interrupted their favorite soap operas.

“Nixon vetoed the funding bill, cut our funding and now he’s giving us our best programming,” Karayn told Time magazine in 1973. “It’s sort of like being reborn.”

Nixon resigned in August 1974. But the unintended boost he gave to PBS public affairs programming endured.

“Bill Moyers Journal,” the PBS series that began in 1972 and was fronted by the Johnson administration’s former press secretary, was elevated by its coverage of the Watergate scandal and made its host one of television’s most respected news commentators.

In 1975, PBS gave MacNeil carte blanche to develop a nightly news program. He launched “The Robert MacNeil Report,” which was designed as a supplement to the network evening newscasts. While CBS’ Cronkite or NBC News anchor John Chancellor devoted a few minutes to each story, MacNeil analyzed a single topic for a full half-hour every weeknight.

The program made its debut on New York public station WNET and by the following year went national when the Washington-based Lehrer joined the program as co-anchor. It was rechristened as “The MacNeil/Lehrer Report” and in 1983 expanded to an hour, making it the first hourlong evening newscast on broadcast network television and a signature series for PBS.

While TV news changed over the decades, “The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour” remained true to its original mandate of providing sober, serious discussion of domestic and international issues. When the trial of O.J. Simpson became a dominant TV news story in 1995 — driving up the ratings for the commercial networks — the “NewsHour” devoted scant attention to it outside of the verdict.

“They were very serious people,” said Richard Wald, a former news executive for NBC and ABC. “In private, Lehrer was very funny and famous for telling wacko stories. I never at any time heard him say something funny on the air.”

The anchors, free from the pressure to deliver ratings, never apologized when critics suggested the program did not chase the most popular stories or follow the trends of ad-supported TV news programs and channels.

“The mission from the beginning has been to cover what has the potential to change people’s lives,” said Woodruff. “That’s what Jim and Robin did in the beginning, and that still holds today.”

MacNeil, who stepped away from the anchor desk in 1995, knows that maintaining the program’s temperate approach has not gotten any easier.

“It is more difficult for the ‘PBS NewsHour’ to run political discussions — which our original report helped to invent — and keep the the argument civilized and coherent,” he said. “That effort can make the ‘NewsHour’ seem tame while for the red-meat audience, Fox News or MSNBC or CNN are more exciting.”

The “NewsHour” has evolved over its long run. In 2013, following the retirement of Lehrer, who died in January, the program became the first network newscast to be anchored by two women, Woodruff and the late Gwen Ifill.

It has adapted to new video platforms, streaming full programs for free on demand through PBS station websites, Facebook and YouTube. In 2019, the program added a West Coast newsroom out of Arizona State University that provides updates after its first airing in the Eastern and Central time zones.

In the era of political tribalism on cable news, where viewers can find channels and hosts suited to their particular persuasion, the “NewsHour” — which averages around 2.3 million viewers a night, according to Nielsen — has remained politically even-handed. And that’s the way PBS viewers like it.

Research firm GfK found in a 2019 survey that 28% of PBS viewers identify as Republican while 33% said they were Democrats and 34% said independent — in line with the breakdown for the entire U.S. adult population.

Federal funding for PBS has been targeted by Republican politicians over the decades. Those efforts have largely failed as the service has support from constituents back home who come from both sides of the political spectrum despite the heightened polarization in the country.

“I think that people just assume that we lean one way or another and we don’t in terms of the audience,” said PBS Chief Executive Paula Kerger. “I think that’s important because I do think people are really looking for a place where people who have different perspectives are coming together.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.