HBO Max is doing fine. But is streaming actually a good business?

This is the Jan. 11, 2022, edition of the Wide Shot newsletter about the business of entertainment. If this was forwarded to you, sign up here to get it in your inbox. By the way, this newsletter is now 1 year old. Cool, right?

Way back in early 2021, during the first weeks of this newsletter, we asked readers to fill out March Madness-style tournament brackets for what everyone had decided to call the “streaming wars.”

Those who’d picked HBO Max as the ultimate victor (and some did, actually) might have understandably received askance looks. The service had stumbled after launching in May 2020 with muddled marketing, a glitchy app and a relatively high $15-a-month fee.

In the last 12 months, enough has changed to support WarnerMedia Chief Executive Jason Kilar’s claim to my colleague Meg James that “2021 was the year that HBO Max broke through.”

The streamer’s parent company AT&T last week disclosed that HBO and HBO Max reached 73.8 million subscribers at the end of the year. That represented an increase of about 4.4 million subscribers over third-quarter numbers reported in October and exceeded the company’s earlier guidance of 70 million to 73 million.

The pace of growth for HBO and HBO Max is solid compared with its biggest rivals. The much-cheaper Disney+, launched in November 2019, grew by 2 million in the most recent quarter to 118 million global subscriptions. Netflix (in the lead still at 214 million) added 4.4 million in its latest tally.

Additionally, HBO Max was the most-downloaded streaming video entertainment app last year in the U.S., according to Apptopia, topping Disney+ and Netflix.

For Kilar, in the midst of a presumed lame-duck period ahead of the entertainment company’s merger with Discovery, the numbers partly vindicate WarnerMedia’s strategy of putting all of Warner Bros.’ 2021 movies on the service simultaneously with their theatrical releases. Shows like “The White Lotus” and a massive film and TV archive also helped.

With the streaming landscape expected to consolidate into an industry dominated by three or four companies, HBO Max is in a strong position.

Yet as fun as it is to imagine Walt Disney Co. CEO Bob Chapek, Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos and Discovery boss David Zaslav in a corporate cage match for the streaming championship belt, the question of winners and losers may be the wrong one to ask.

The better line of discussion is the one that some analysts have been getting at for a while: Are we sure streaming is a good business?

That’s the main question media analyst Michael Nathanson of MoffettNathanson pondered in a recent in-depth research report on the state of streaming going into the new year. Wall Street’s fixation on quarterly streaming subscriber numbers has come with “a distressing lack of focus on streaming economics,” Nathanson argues.

One of the major points Nathanson offers is that it’s really, really expensive to stay competitive in streaming. Keeping viewers’ attention means constantly putting out fresh shows and movies. A hit series will debut with a big surge in viewership and quickly taper off. The binge-and-burn nature of online viewing, coupled with the growing rivalries between the major streamers, is driving companies to spend even more on content.

Disney has said it will spend $33 billion in fiscal 2022, an annual increase of $8 billion, as it tries to boost Disney+, Hulu and ESPN+. Nathanson estimates the combined Warner Bros. Discovery (assuming regulators approve the merger) will deploy $26.7 billion on content this year, including sports programming. He projects that the content spending of media companies will account for 50% to 70% of revenues in 2022.

“The truth about content spending for media companies looking to make [direct-to-consumer] pivots is there is no real end in sight,” Nathanson wrote. “Whereas media companies before could only program around limited linear time slots during the day as well as their own studios’ release strategies, thanks to the unlimited, endless potential of content on streaming services, this level of spending should continue to ramp for any company that can afford to compete.”

The big expenditures put pressure on profits, even among those with the strongest subscriber numbers. Increased spending by Netflix, which is expected to deploy $19 billion on content in 2022 (up 10% from the prior year), will continue to weigh on cash flow. Nathanson estimates that Netflix’s free cash flow margin will shrink to 2% in its current fiscal year, though it should steadily rise in the future.

At least HBO Max is charging $15 a month, which gives it a higher average revenue per-user (ARPU) than cheaper rivals. The comparatively steep monthly fee, considered a disadvantage early on, could actually be a benefit for offsetting massive content spending.

The upheaval brought on by streaming has cost traditional media companies in multiple ways, some that show up on a balance sheet, and some that don’t.

We’ve written a lot here about how WarnerMedia angered talent when it shifted its entire 2021 movie slate to simultaneous streaming. Christopher Nolan, who once called HBO Max the “worst streaming service,” decamped from Warner Bros. to Universal Pictures for his next movie. To ease tensions, WarnerMedia paid filmmakers and actors like Will Smith upfront as if their movies had been box-office hits.

The HBO Max film strategy is changing in 2022, but the pre-pandemic business model is over. Warner Bros. is cutting its theatrical output by nearly half, sending many of its movies directly to streaming this year. The movies that are planned for theaters are getting a mere 45-day window in multiplexes.

Companies have to adapt to changing times. Disney CEO Bob Chapek, in his new year’s email to employees sent Monday, stressed the importance of storytelling, innovation and putting the audience first as the three pillars of his strategy.

“At the end of the day, our most important guide — our North Star — is the consumer,” Chapek wrote. “Right now, their behavior tells us and our industry that the way they want to experience entertainment is changing — and changing fast thanks to technology and the pandemic. We must evolve with our audience, not work against them. And so we will put them at the center of every decision we make.”

At the risk of over-analyzing, that doesn’t sound like a company that’s committed to old models, like putting Pixar movies exclusively in theaters.

Companies are willing to shake up their 100-year-old legacy businesses (these old-fashioned things called movie studios) on the idea that streaming represents a better future, or at least one in which they remain relevant in a world of TikTok, video games and metaverses. It’s fair to ask if streaming really is the better way.

Inside the Golden Globes

This year’s Golden Globes were basically given by press release, in a major shake-up of the awards season landscape. No celebs, red carpet, audience or big-name host onstage at the Beverly Hilton’s ballroom.

Stacy Perman and Christi Carras covered the weirdest Globes ceremony ever, which took place untelevised as a result of a Times investigation into allegations of ethical lapses and diversity problems at the Hollywood Foreign Press Assn.

Their lead: “Long billed as Hollywood’s ‘party of the year,’ Sunday’s Golden Globes more closely resembled an intimate tax attorneys’ convention. Although the evening was black-tie, the usual fizzy mood was gone.”

Top honors went to “The Power of the Dog,” “West Side Story” and “Succession.”

Stuff you should be reading

— R.I.P. January has been a cruel month, in terms of celebrity deaths. Two film icons lost in one week: Sidney Poitier, dead at 94, and Peter Bogdanovich, at 82. On Sunday, comedian Bob Saget died at 65.

— Anime wars. AMC Networks acquired “Made in Abyss” distributor Sentai and anime streamer HIDIVE (Variety). Analyst Julia Alexander smartly pointed out that this is just the latest deal by a major media company in the Japanese animation space, with Sony’s ownership of Funimation and Crunchyroll and Netflix’s deals with NAZ, Science SARU, MAPPA and Studio Mir.

— After turning journalists into TV stars and millionaires, Richard Leibner signs off. “Every time a TV news star signs a multimillion-dollar contract, he or she might want to take a silent moment to thank ... Leibner, even if he had nothing to do with the deal,” writes Stephen Battaglio. “Leibner, 82, the godfather of TV news agents, retired at the end of December after 58 years of representing many of the biggest names in the industry, including Diane Sawyer, Dan Rather, Mike Wallace and Norah O’Donnell.”

— Ben Affleck is done worrying about what other people think. The star of “The Tender Bar” and “The Last Duel” gives great interviews, including this one with Josh Rottenberg. He has plenty of candid thoughts on the state of the film business, especially the kinds of grown-up dramas he’s clearly interested in making. If Affleck for some reason decides to pivot and start an entertainment industry newsletter, I’m in big trouble.

— Norman Mailer, canceled? Sort of? Former Times books editor Carolyn Kellogg weighs in on the murky debate surrounding the publication journey of a new collection of writings by Mailer after a story by Michael Wolff in the Ankler alleged that Penguin Random House dropped the book for fear of backlash. “So what we have is a Mailer not canceled but brought back to life; he is once again the subject of controversy,” Kellogg writes. “I imagine that would suit him just fine.”

— Where does Jon Stewart’s comedy go from here? From Esquire’s analysis of Stewart’s J.K. Rowling-related flap: “The comedian’s brand of satire once made him the perfect culture critic. But as his latest internet imbroglio proves, his smarter act is out while righteous indignation runs amok.”

— If the film industry ever truly dies, its final death cry will be the sound of studio honchos closing out their tabs at the Polo Lounge. The New York Times’ Brooks Barnes captures the scene at the classic Hollywood haunt.

Number of the week

Another week, another $1 billion valuation for a top production company. This round’s hot seat occupant is AGBO, the Los Angeles-based production firm launched by “Avengers: Endgame” directors Joe and Anthony Russo and producer Mike Larocca. AGBO was valued at $1.1 billion after receiving a $400-million investment from Tokyo-base game maker Nexon for a 38% stake.

The Russo brothers directed some of Marvel’s biggest hits, like “Captain America: Civil War.” Their company produced “Extraction,” one of Netflix’s most-watched movies. The siblings aren’t quite household names on the level of Reese Witherspoon, LeBron James or Will Smith, who’ve all made recent deals with sky-high numbers for their companies. But the AGBO deal is yet another example of both the demand for content and the scarcity of artist-led enterprises.

Hollywood production

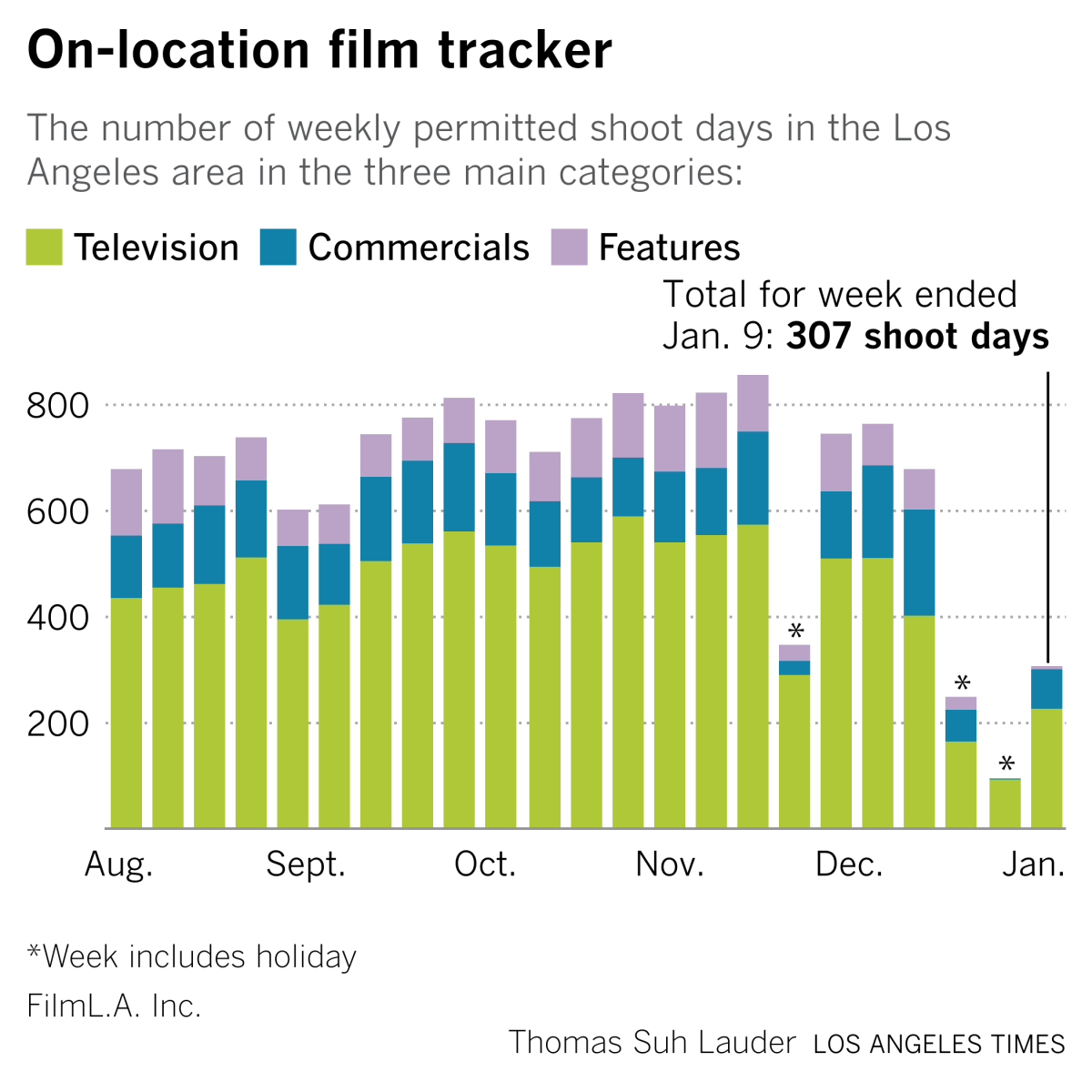

The Omicron variant has led to numerous cancellations and digital pivots for entertainment industry events. The Sundance Film Festival canceled its in-person plan. The Grammys and Critics Choice Awards were postponed.

Has there been a noticeable effect on Hollywood film and TV sets? COVID-19 concerns have delayed the return to work for some productions, my colleague Anousha Sakoui reported last week. It’s hard to say how much Omicron affected production schedules, purely based on FilmLA’s weekly data. Comparing with prior years isn’t super helpful, because the holiday falls on different days of the week.

Finally... Elmo’s fire and fury

Apparently nothing reflects the national mood in early 2022 better than a video of Elmo (yes, from “Sesame Street”) losing his mind at the prospect of having to give up an oatmeal raisin cookie — his favorite! — to a pet rock.

Hey, I get it, man.

As Times staff writer Christi Carras explains in her piece, an old video of Elmo going off on his friend Zoe and her inanimate pet rock, Rocco, went fully viral on social media last Tuesday.

For those not familiar with the longstanding Elmo-Rocco feud and the gaslighting our perpetually 3-year-old friend has endured, Carras’ timeline is an invaluable resource.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.