After turning journalists into TV stars and millionaires, Richard Leibner signs off

Every time a TV news star signs a multimillion-dollar contract, he or she might want to take a silent moment to thank Richard Leibner, even if he had nothing to do with the deal.

Leibner, 82, the godfather of TV news agents, retired at the end of December after 58 years of representing many of the biggest names in the industry, including Diane Sawyer, Dan Rather, Mike Wallace and Norah O’Donnell.

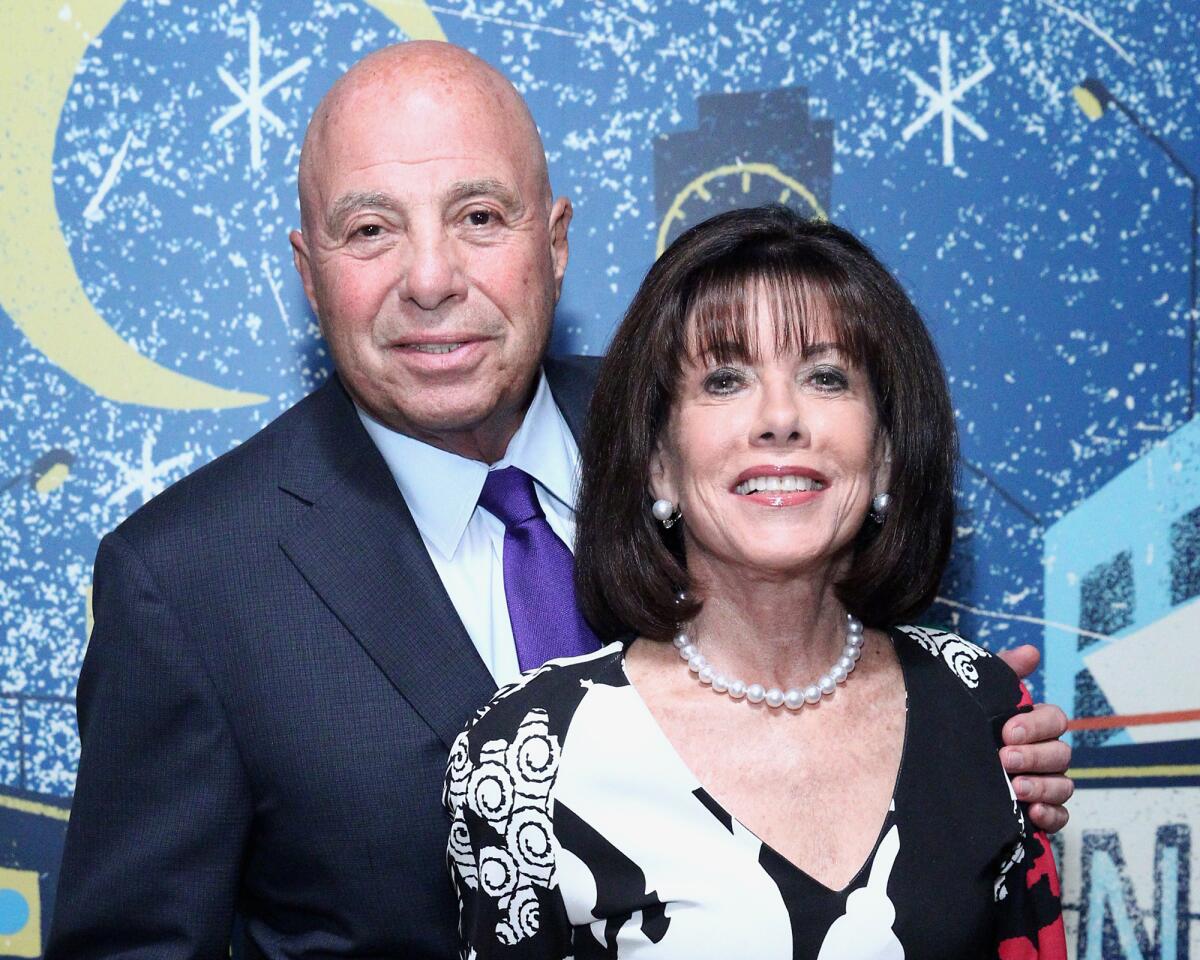

His agency, N.S. Bienstock — acquired in 2014 by UTA, where Leibner continued to work alongside his wife and partner Carole Cooper — had an outsized influence on how the country gets its information as well as the incomes of the people who deliver it.

“He has been a force to be reckoned with,” said Andrew Heyward, a research professor at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Communication at Arizona State University. “You could not be an effective news executive without having a relationship with him.”

Even competitors of Leibner and Cooper sing their praises.

“Richard Leibner and Carole Cooper were the class of the business — it’s as simple as that,” said Michael Glantz, a partner at ICM. “Not only were they the best of what they did, they were always supportive of the people who worked for them.”

The Brooklyn-born Leibner graduated from the University of Rochester and joined his father’s New York City accounting firm in 1964. Their clientele was mostly music publishers and small record companies that populated the Brill Building in Times Square.

Leibner and his father eventually joined forces with Nate Bienstock, a life insurance salesman whose clients included CBS News commentator Eric Sevareid and author John Steinbeck. As more journalists started doing television work in the 1960s, Bienstock started handling contracts for them as a side business.

Since becoming a full-time correspondent on “60 Minutes,” Bill Whitaker has traveled to Cremona, Italy, to report on Stradivarius violins; to France for a story on newly discovered Picassos, and to Myanmar to sit with Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi.

The younger Leibner observed Bienstock, the agency’s namesake, and the growth of the TV news business as the events of the turbulent decade played out.

Correspondents and anchors who covered the Vietnam war and the civil rights movement were becoming household names. Soon, Leibner was representing television news talent, who at the time did not command the income generated by actors, writers and directors working in TV and film.

“The major agencies were all focused on movies and television and making the big money in package fees,” Leibner said in a recent telephone interview. “We were specialists, and that’s how we got the foothold and got ahead of everybody.”

By the end of the 1970s, Leibner’s client roster included Rather, Morley Safer, Mike Wallace and Andy Rooney, all part of the cast of “60 Minutes” as it grew into the most popular news program of all time.

Leibner represented Sawyer when she became the first woman correspondent on “60 Minutes,” and Ed Bradley, the program’s first Black journalist. He later engineered Sawyer’s move to ABC News. Bienstock also accrued a roster of anchors on local stations as they added hours of local news programming.

But the real sea change occurred in 1977 when ABC’s sports impresario Roone Arledge, who turned the Olympics into a major TV event during the decade, was given oversight of his network’s also-ran news division.

ABC had already shown a willingness to pay big salaries, having poached Barbara Walters from NBC with the first $1 million a year contract for a news anchor. When Arledge came in, he was laser-focused on building a contender and Leibner took full advantage of the situation when venerable anchor Walter Cronkite was ready to give up the chair at “CBS Evening News.”

Arledge aggressively pursued Rather for ABC News. He stayed at CBS, but Leibner used the offer as leverage to get him named as Cronkite’s successor — even though it had been promised to CBS News Washington correspondent Roger Mudd. Rather’s new assignment came with a record-setting contract that paid $2.2 million a year.

Arledge kept spending to attract big names to ABC News, which saw its ratings and stature rise. He told Leibner to bring him clients who felt underpaid. Salaries throughout the TV news business rose as a result.

“Richard broadened the definition of talent in the television news business and increased its value enormously,” said Heyward, who as president of CBS News from 1996 to 2005 frequently dealt with Leibner. “Not just for the big name stars, but for other people that may not be in the top echelon. You had this phenomenon of associate producers walking around saying ‘I have another year in my contract’ with no irony. This was a new thing.”

When CNN was launched in 1980, Leibner’s firm helped stock the channel with credible journalists, including its first hire, Daniel Schorr, whose aggressive reporting at CBS News earned him a spot on the Nixon White House’s enemies list.

Some of Leibner’s clients have been with him for decades, perhaps because he was a fierce advocate for them deep into their careers.

Current “60 Minutes” correspondent Bill Whitaker first signed with Bienstock when he was toiling as a local TV reporter in Charlotte, N.C., in the mid-1980s. They charted a plan, and soon Whitaker landed at CBS where he became a regular presence on the “CBS Evening News” as a correspondent out of its Los Angeles bureau.

Whitaker was content in his role at “CBS Evening News.” But his ambition to be on “60 Minutes” — still considered the brass ring of TV news jobs — never went away.

Whitaker discussed the goal with Leibner, eventually figuring “that ship had sailed.” But two years after their last chat about the subject, he was summoned to CBS News headquarters in New York and was offered a job on the program in 2016.

“I’m pretty sure Richard was bugging them to death,” Whitaker said. “He does the fighting for you. I remember one time I was at a CBS Christmas party and an executive walked up to me and said ‘your agent is a SOB.’ And I remember thinking to myself, ‘Well good, that’s good to know.’”

The devotion to clients can lead to disappointment. Bienstock has seen some of the talent it nurtured, including Bill O’Reilly, former MSNBC host Chris Matthews and former CBS News morning anchor Charlie Rose, go down in flames due to sexual harassment allegations. Rather left CBS News in disgrace following a false report on former President George W. Bush’s National Guard record.

“It’s disappointing but you’ve got to accept the fact that you take the good with the bad and not let it get you sick,” Leibner said. “I have a shaved head because I was balding and I’ve always said the condition at the top of my head is not purely genetic.”

N.S. Bienstock was always a family business for Leibner. His wife, a former TV commercial producer he met on a blind date in 1962, joined the firm in 1976. Carole Cooper helped develop the careers of Bill O’Reilly, Megyn Kelly and CNN’s Anderson Cooper, whom she still represents at UTA where she continues to work. As a team, Leibner and Cooper complemented each other.

“She knows my excesses,” Leibner said. “I’m infamous for my off-color sense of humor, which would get in serious trouble now. She knows when to stop me from telling dirty jokes. She also had more confidence in my ability to take risks and do things than I even thought. I guess our marriage has lasted as long as it has, and has been as good as it is, because we’re not afraid to be critical and honest with each other.”

Zoom and video conferencing, once a last resort for TV news shows, are here to stay.

The Leibners have two sons, Adam and Jonathan, who grew up in a home where their parents watched three-quarter-inch video cassettes of on-air talent from around the country. Evenings were spent in front of three television sets, each showing a network newscast. After getting law degrees, they joined Bienstock as well.

Leibner’s savviest hires outside of his own brood were the business affairs executives who came from the networks.

“We brought in people who knew what everybody was making,” Leibner said. “We were able to build everybody’s salary base because we had more knowledge than anybody else.”

Naturally, old guard network news executives were not happy with how Leibner’s agency disrupted their business model. Ed Joyce, a CBS News president in the early 1980s, referred to Bienstock as “flesh peddlers.”

There were also questions over how well Leibner’s agency could serve its clients when it had so many of them competing for a limited number of plum positions.

When asked about conflicts, Leibner always pointed to his track record. “We got the talent in front of the camera and behind the camera a fairer share of what the business was grossing,” he said.

Leibner gained a reputation as a bombastic personality, speaking in a nasal accent that evokes the streets of the Flatbush neighborhood where he grow up. His midtown Manhattan office had a Rock-Ola juke box stocked with early rock ‘n’ roll and Frank Sinatra tunes. But Heyward said Leibner’s shtick stopped once he was seated across a negotiation table.

“You might think he left it to others to sweat the small stuff,” Heyward said. “Not at all. He’d come into the office with a yellow legal pad, and he was very focused on details. There were few or no histrionics even though he was a showbiz type character with a big personality.”

Leibner will now devote his time to his family’s foundation, which contributes to organizations that provide scholarships for students wanting to get into the TV news business. He is also a major supporter of the Library of American Broadcasting Foundation which houses the papers of journalists at the University of Maryland. He wants to preserve the history of the TV news business, but fears for its future as the audience is increasingly drawn to seeing its views validated instead of to the facts.

“What concerns me is the fact that cable news is opinionated at night and we get a non-politician who becomes president for four years and makes it a religion to attack journalism,” Leibner said. “This game of everybody worried about their ratings and attacking each other is doing nobody any good.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.